On 22nd December 1986 the English filmmaker Derek Jarman received a positive HIV diagnosis. He was 44 years old.

In the mid-1980s, an HIV diagnosis came with a life expectancy of just 15 months. When Jarman received the news, he decided to move out of London for a while. He wanted to spend some time living by the sea. So a few months later he bought a small fisherman's cabin for £32,000, using an inheritance he'd received from his father.

Derek Jarman's Garden #14

2022

Robert Priseman

The cabin is called Prospect Cottage and is situated on the shoreline of Dungeness, along the Kent coast. The beach there is sparse and offers a landscape of seemingly bleak obscurity. Just a few boats and houses stretch along a vast expanse of shingle – nothing else, no trees, no fields. Only the sea to the south and Romney Marsh to the north. Yet empty places can conceal a lot.

Once he'd settled in, Jarman decided to reshape the gravel beach which surrounded his new home. He resolved to turn it into a sculpture garden. And although there was little to work with, he managed to nurture santolina, valerian and crambe plants which could endure the unforgiving coastal environment. He collected driftwood and discarded rusting metal engine parts that had previously been used to winch boats from the sea. From these he created sculptures. He gathered large cobblestones together, upended and buried them to form small-scale arrangements which are somehow reminiscent of miniature stone circles and graveyards.

Prospect Cottage and the garden which now surrounds it are humble in scale, occupying a modest 115 square metres. In his journal, Jarman wrote that forming the garden had acted as 'a therapy and a pharmacopoeia' for him. Eight years after moving there, he died of AIDS-related complications and the project came to an end.

Yet where Jarman's life ended, his sculpture garden slowly began to acquire a significance of its own. And while he didn't create this project for an audience, today it attracts thousands of visitors every year. In fact, it has become a place of such significance that 32 years after his death, the Art Fund led a campaign to buy it. They raised £3.5 million in 10 weeks and, on 1st April 2020, acquired Prospect Cottage for the nation.

Derek Jarman's Garden #10

2022

Robert Priseman

What then makes Derek Jarman's personal and intimate undertaking to create a sculpture garden so significant?

At its heart, Jarman's garden is an expression of pure creativity. It lays bare for us the very essence of why, sometimes, we are driven to create art. While we can only guess at the emotional impact a positive HIV diagnosis would have had on him, we can see that it triggered a desire to buy a home by the sea. This reveals a direct response he took to the news which affected him profoundly.

Once in his new home, Jarman wrote how the process of crafting a sculpture garden felt somehow healing to him. Because there is no cure for HIV, and there was no knowledge of how to manage it at that time, we understand that the healing process he refers to is not related to physical recovery – but instead, it talks to soothing emotions.

In a significant way, Derek Jarman reveals to us that the drive to create can help appease disturbing feelings. This happens when the invisible and amorphous sensations we feel on the inside are transformed into something tangible on the outside. This tangible manifestation acts as a metaphorical chalice: being manifest enables our emotions, for a while at least, to be tamed.

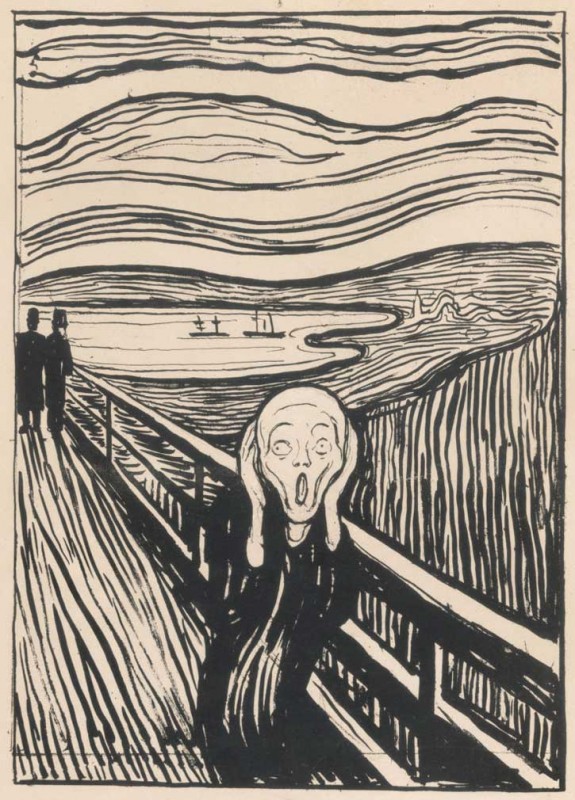

This process of soothing emotions through art was examined in 335 BC by Aristotle in his work Poetics. In this book, Aristotle explores the mechanics of poetry, specifically in relation to how it is performed. Central to his thesis is the idea that poetry enables our sensitivities to be eased. Talking specifically about how tragedy can enable emotional catharsis, Aristotle wrote: 'Tragedy reduces the soul's emotions of terror by means of compassion and dread. It wishes to have a due proportion of terror. It has pain as its mother'.

For Aristotle, catharsis in the arts acts on our psyche in the same way as a vaccine does on a virus. By experiencing a small amount of an emotion, at a distance, we gain an angle on how better to navigate difficult feelings.

While Aristotle talks particularly about the audience experience, the same is true for the creator. Art offers a 'safe space' where we are able to consider complex feelings. Our sensitivities are internal and invisible, awakened by events which happen to us. We have no real power over our emotions and the way they arouse us. Our only control is in how we respond to them. Exploring emotions through creativity, either by making works of art or viewing them as part of an audience, allows us in some small way to grasp how we might approach feelings which can threaten to overwhelm us.

On the west side of Prospect Cottage, Jarman had inscribed John Donne's poem The Sun Rising.

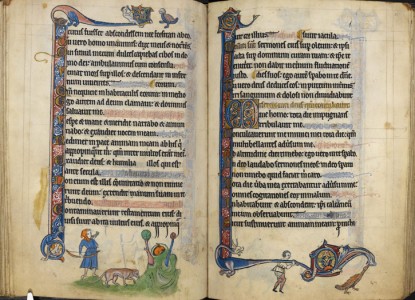

Donne lived from 1572 to 1631 and during different stages of his life worked as a soldier, Member of Parliament, priest and poet. As a writer, Donne's output could just as easily have been directed to conceiving sonnets for publication or sermons for reading in the church. Both use the same skills, syntax and grammar, but they employ their abilities to different ends.

Like Donne, Derek Jarman had an abundance of creative energy. We witness this through seeing how his life had been dedicated to making films and paintings, and to gay rights activism. For his last eight years, he also turned his creative output to sculpting the garden at Prospect Cottage. This was designed specifically to address his own emotional welfare.

Many artists and writers like Jarman and Donne express their creativity in a variety of ways. And through them, we observe how creativity is not an inherited genetic trait. Instead, it is an energy which materialises, just as spring water breaks the surface to form a stream. And maybe this is why so many of our greatest writers and artists emerge from unassuming surroundings, with no previous family history in the field. True creativity, it seems, is modest and personal.

Just as artists had before him, Derek Jarman took the raw material of his sensitivities and sought to externalise them. He brought together and reassembled a variety of things that already existed in the world – seeking out objects from the beach, which he reformed into unique displays. In doing so, he reveals to us that the real gift of creativity is not found in financial reward. Instead, it is found in possessing a little time and space where one can produce something of meaning for ourselves. Something which at first only exists in our imagination, and is then realised into the world.

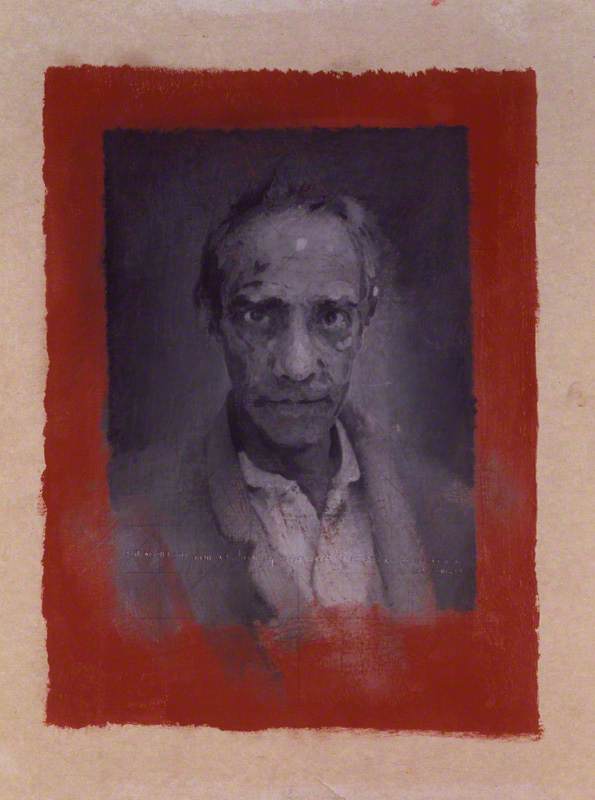

Derek Jarman's Garden #13

2022

Robert Priseman

In Dungeness, Jarman had the small luxury of limited time and space. With this, he utilised the readily available material the beach provided. Free of institutional constraints and indifferent to finding an audience, he produced art for art's sake, a pure expression which is not subservient to another cause.

Leonardo da Vinci famously said 'Art lives from constraints and dies from freedom.' At Prospect Cottage we can see the whole creative process of a pure art is played out. We observe how a diagnosis created an emotional trigger which in turn initiated the buying of his chalet and the subsequent desire he felt to make a sculpture garden. The lack of finance produced a constraint which enabled creativity to thrive. This led to the use of small-scale found materials from the beach, which was compounded by the limited size of the garden itself.

In designing his garden, Derek Jarman conceived an art out of nothing. His sculptures acted as receptacles for his emotions during their formation. Once fixed in place they then became transmitters of his sensitivity – and we, the receivers.

Robert Priseman, artist, curator and writer