Jules Clarke in her London studio

In this interview, Robert Priseman – founder of The Priseman Seabrook Collections – talks to the artist Jules Clarke about her emotional relationship with film, finding the sinister in the

Robert

You were born in New York then moved to London. I wonder what brought you here and if the legacy of previous generations of artists impacts on the way you think about your practice?

Jules Clarke: I moved to London as a reluctant teenager in 1989 for my father’s job – he worked for Cadbury’s. We weren’t supposed to stay for long, but I never ended up moving back to the US.

I admire artists like Peter Doig, who draws on his Canadian childhood but seems to integrate the nostalgia with a greater perspective into something like a personal magical realism. Perhaps his UK perspective freed his memories from Canada in some way? I think there is great value for the expat in having perspective on your native country, as well as

Red Curtains came from a ‘You’ve Been Framed’ episode where two people are laughing and falling into some curtains... There seemed to be something familiar and domestic, and also sinister and menacing about the composition.

Robert: Many creative people are considered ‘outsiders’ to their communities in some way. Do you think a forced disconnection is a benefit to the creative process?

Jules: I’m interested in a kind of observation which takes into account the alienation one feels from technology – in the infinite number of images and the speed of information and how it affects our perception. A painted image, as a hand-made surface created over long periods of time, feels like a resistance to this.

Robert: The images in your work

Jules: I have always been interested in finding the extraordinary, or sometimes the sinister, in the everyday. I like the idea that mundane subjects can reveal something significant through the medium of painting.

I started working

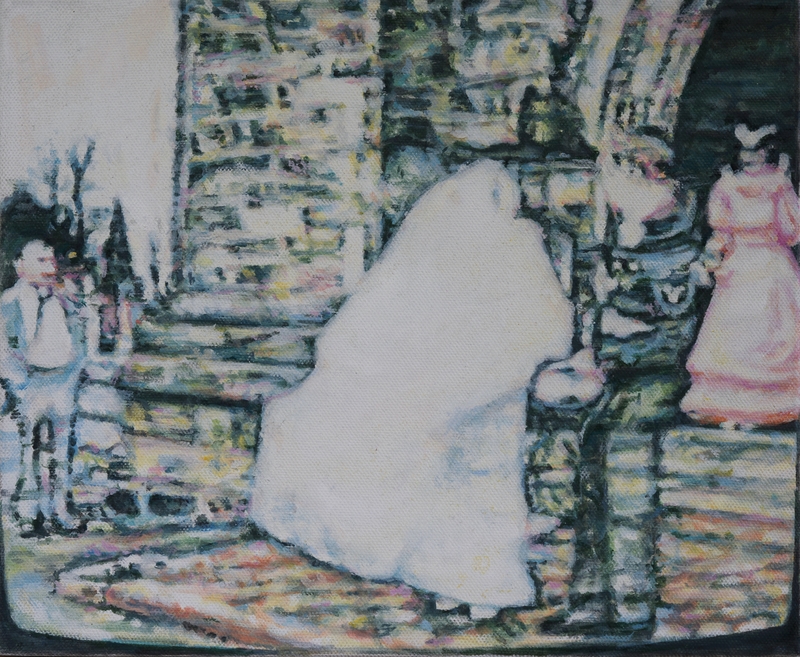

Begin at the Beginning

oil on canvas, 25 x 30 cm by Jules Clarke

I am also very absorbed in domestic life, with two daughters and a third on the way! The hours of isolation in the studio are always counteracted (and have to interact, to a degree) with family life – balance is often difficult to maintain. I have been thinking a lot about the recent Vanessa Bell exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery, and her successful and

Robert: It is true to say that all of your paintings are sourced from video stills and photographs. Do you take any of these images yourself, or do you acquire them all second-hand?

Jules: My sources are always photographs I take of the moving screen – I don’t freeze the frame as I’m interested in the surprising and distorted things the camera often does to compensate for the lack of information as it tries to deal with extracting a still image from a moving one. It seems to relate to one moment becoming another, and to the act of memory, which is often very distorted.

Robert: What is it about creating a sense of emotional separation from the world you observe that appeals so strongly?

Jules: I like the objectivity of preserving the way technology presents a moment – the interaction of the moving image with the physicality of the screen, and the camera’s ability to record, and often distort, a moment. It seems like this detachment can unlock what is significant, more than I could through fabrication or imagination.

But there is a physical side to the painting that seems important too – I try to use the paint in a very fluid way, in many layers over time. There has to be an element of independence for the paint, somewhere between referring to the source and retaining a material independence.

Also, I am always drawn to areas of ambiguity, since I find this resists a straightforward emotional or narrative meaning, or can also somehow have more meaning in itself, like when a person starts to resemble an animal or a ghost. I am always faithful to the ambiguities in the image, however, so even if they are areas of abstraction they are actually representational.

Robert: I’m interested in parallels your work draws with the paintings of Walter Sickert. Like you, he was born outside of the UK and moved to London and, like you, he produced paintings of mainly domestic scenes which were often adapted from mass media imagery. For both of you, it is almost as though the artist is a floating and detached observer. What do you think of that?

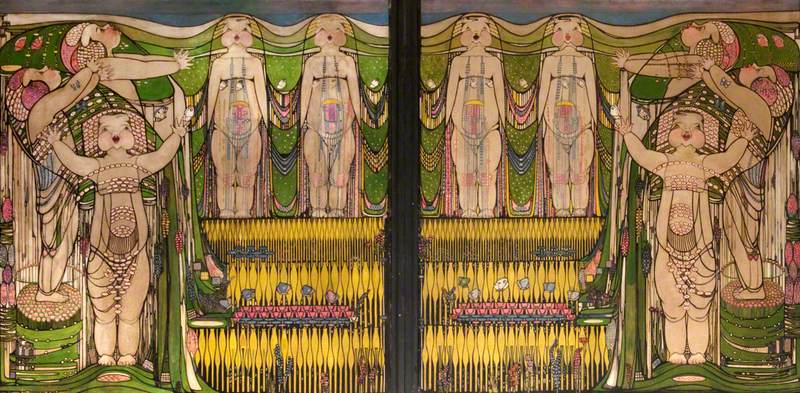

Jules: Although the detached perspective through the filter of mass media imagery is interesting to me in Sickert’s work, I am much more drawn to the work of Jean Edouard Vuillard who was also painting domestic scenes in a similar period. The way distortion and claustrophobia of pattern in Vuillard’s compositions merge the subject with the scene in an ambiguous emotional and metaphorical space is, for me, more unsettling.

Red Curtains

oil on canvas, 30 x 35 cm by Jules Clarke

Robert: How fascinating. When I look at it now it seems very clear that a painting such as your Red Curtains (2016), which appears to show a figure standing in a bedroom, has a very clear and powerful connection to Vuillard’s Le Corsage Rayé (1895), especially in terms of its visual patterning. Can you explain a little more about the ways in which this kind of artistic influence transfers and informs your own practice?

Jules: Red Curtains came from a ‘You’ve Been Framed’ episode where two people are laughing and falling into some curtains. I liked how the patterns and

Deux ouvrières dans l'atelier de couture (Two Seamstresses in the Workroom)

1893

Jean-Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940)

Robert: Who else has a strong influence on your practice as an artist?

Jules: I’ve always been interested in Luc Tuymans for his emotional, but subdued, engagement with reproduced images. Jaqueline

Robert: Do you make preparatory drawings or prefer to go straight to paint?

Jules: I have the photographs made into old-fashioned slides and project those to draw directly onto the canvas, or sometimes onto paper. I like the process of drawing from these shadows, relating to film and projection. It allows more fluidity than a grid for me, like imprinting the traces of a projection.

Robert: I get a sense that the abstracted patterning apparent in Vuillard’s paintings creates both an emotional separation and connection with his mother, who was a dressmaker. For you, abstracted patterning is created by the distortions of the television screen which then sets up an emotional distancing. Does it also create a simultaneous emotional connection, and if so how?

Jules: I think it places the individual within their surroundings, even if the moment is streaming past. My great-grandfather was one of the founders of Metro Goldwyn Mayer, so maybe there is an emotional connection for me in the medium of film and moving image.

Robert: What a special connection to have. I notice how many of your paintings, such as Liesel (2012), Freeman’s Pool (2013) and Brink (2015) are quite monochromatic, whereas other works such as Parade (2012), Begin at the Beginning (2014) and Alice (2016), make use of quite intense

Jules: The ones which are monochromatic allow me to focus more on form, and what I consider ‘drawing’ in

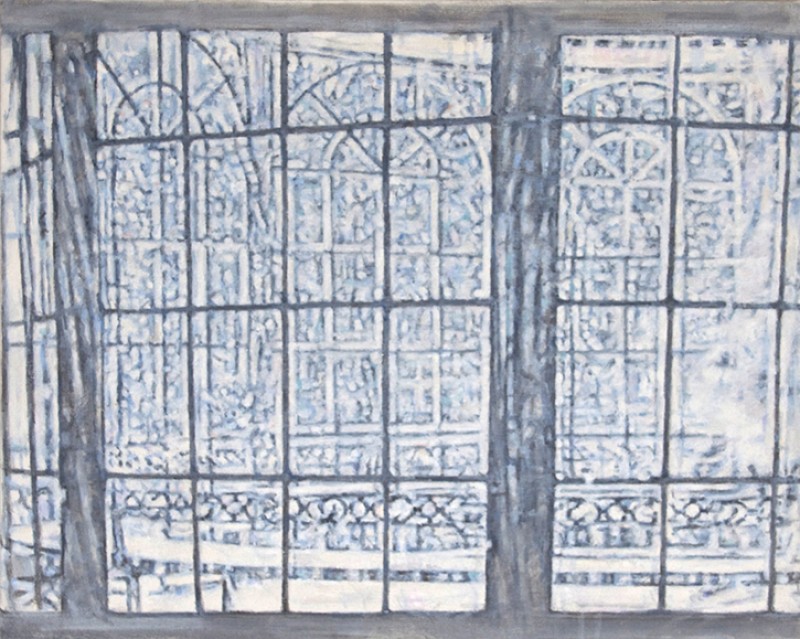

Freeman's Pool

oil on canvas, 40 x 50 cm by Jules Clarke

Robert: One thing which strikes me about your painting is how many of the figures stand still, and seem to occupy the edge of a moment of change. On the

Your use of camera distortion through which to observe these moments seems to provide an outer

Jules: I think that is very insightful and captures the interaction of camera/screen distortion and human emotion, through the filter of the fluidity of painting, which is very much my project.

Robert: Thank you so much for sharing some insights on your work, it has been absolutely fascinating.

Robert