Living in a small flat didn't stop Sir Edward Marsh (1872–1953) from amassing a huge collection of pictures.

Once he had covered his walls from floor to ceiling, Eddie, as he was known to his many friends, started screwing frames to doors (both sides) and then, as his spending spree continued, began lending to galleries. Finally, he gave most of his pictures away.

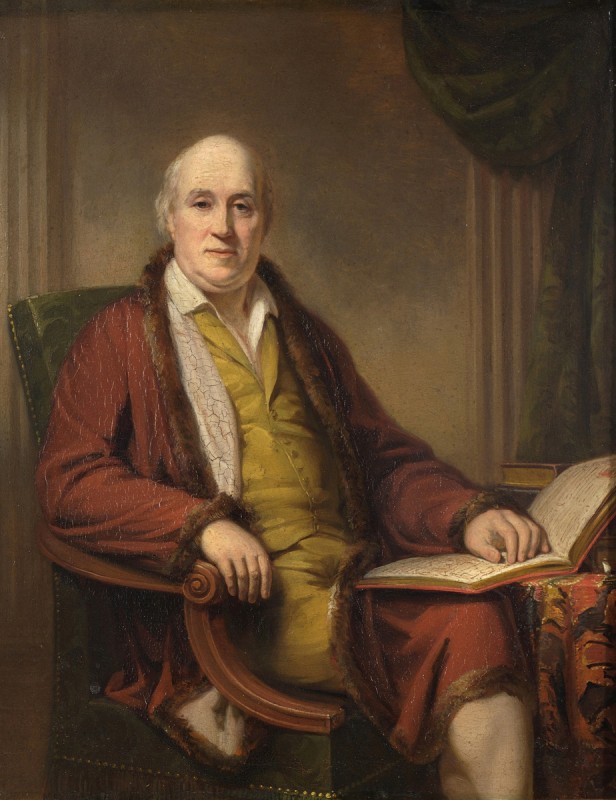

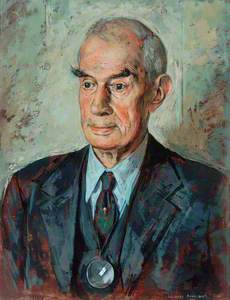

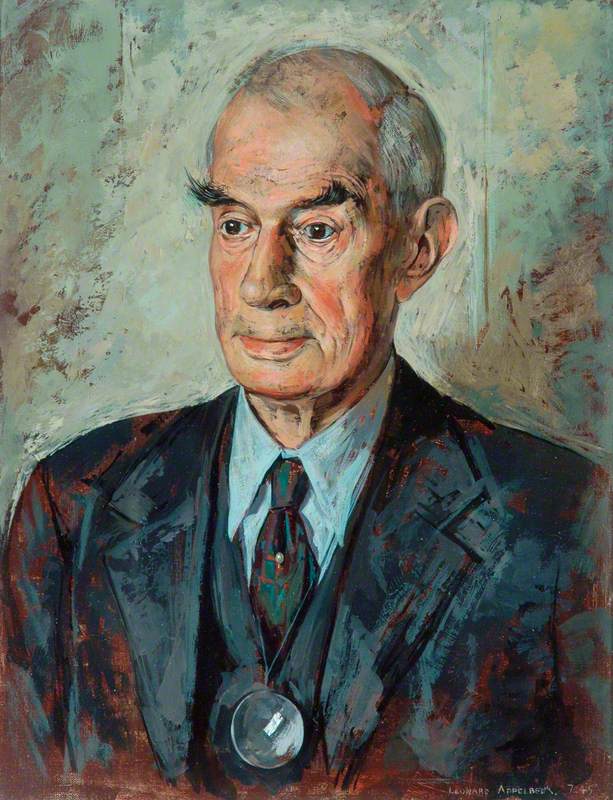

Sir Edward Howard Marsh (1872–1953)

1945

Leonard Appelbee (1914–2000)

Some 350 works from Eddie's collection are now in public galleries across Britain. Thankfully, he dealt not only in quantity but quality. His monocled eye was drawn to the brushwork of a brilliant generation of former Slade students including Stanley Spencer, Mark Gertler and Paul Nash. By the outbreak of the Second World War, he had assembled a magnificent collection of modern British art.

Marsh started by collecting old English masters such as Girtin and Cotman but changed direction when, in 1911, he bought Parrot Tulips by Duncan Grant. Now in Southampton City Art Gallery, it was his first notable purchase by a living artist. He never looked back. 'To buy an old picture did nobody any good except the dealer; whereas to buy a new one gave pleasure, encouragement and help to a man of talent, perhaps of genius,' he wrote in his memoirs.

As a senior civil servant, including 23 years as Winston Churchill's private secretary, Eddie wasn't enormously wealthy but he delighted in helping young artists. One of his forebears was Spencer Perceval, the Prime Minister who was assassinated in the House of Commons in 1812. Several generations later his family, including Eddie, continued to receive compensation and what Eddie described as his 'murder money' was invariably spent on paintings.

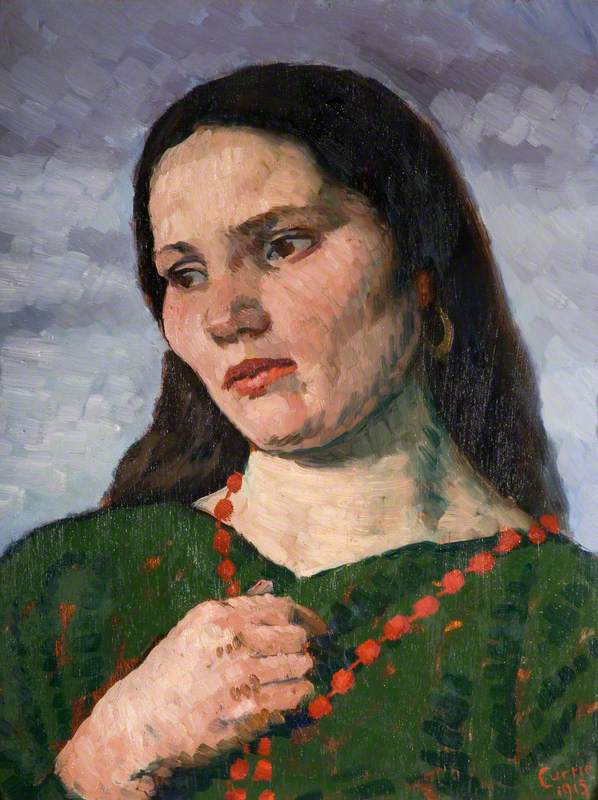

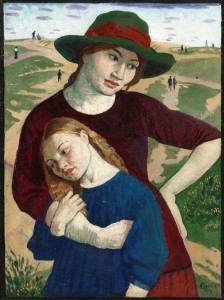

Mark Gertler was a favourite protegé. He bought Jewish Family, bequeathed to the Tate, after visiting his studio in Whitechapel in 1913 and when war broke out gave the struggling artist a monthly allowance. Eddie also bought from Gertler's great friend John Currie and visited him in hospital when Currie shot himself after killing Dolly Henry, his lover. Marsh acquired a portrait of Dolly, Girl with a Red Necklace, now in The Potteries Museum and Art Gallery.

In 1913 Currie and Gertler introduced Eddie to Stanley Spencer from whom he acquired Apple Gatherers, which Marsh donated to the Tate in 1946 to celebrate the end of the Second World War. Completed before he had his first exhibition, Spencer considered it his first ambitious work.

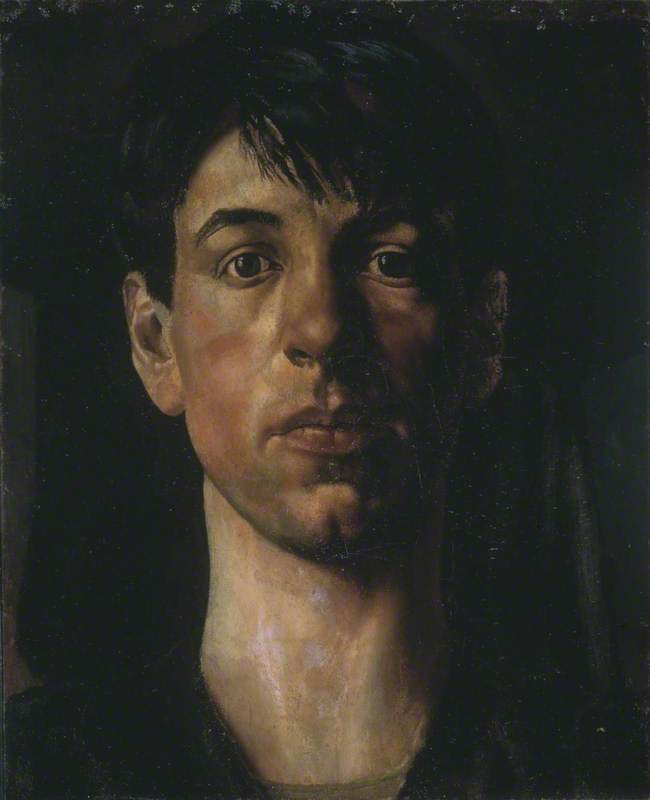

Marsh describes a visit to Spencer's family home in Cookham where he was overcome with the 'lust of possession' after seeing a large self portrait, now also in the Tate.

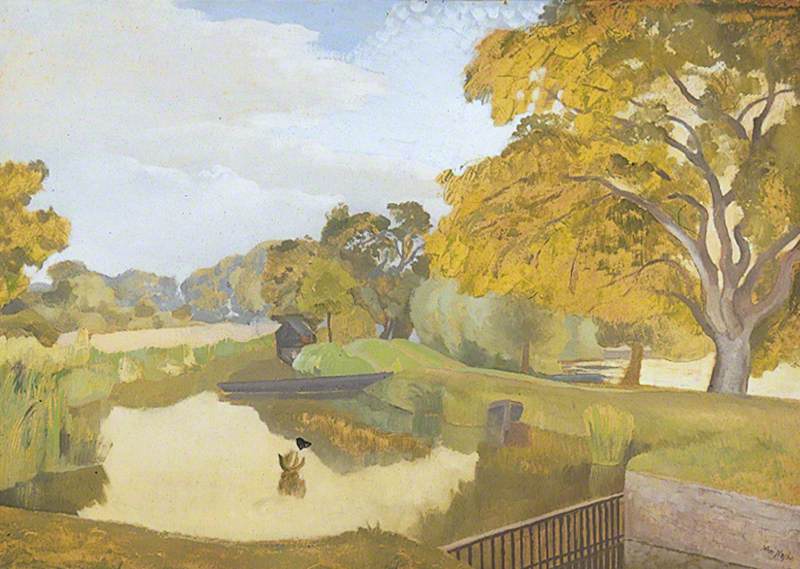

Many of Eddie's artist friends took advantage of the spare bedroom in his London flat at Gray's Inn. The Nash brothers, Paul and John, were frequent visitors. John remembers sleeping in a narrow bed beneath Spencer's Apple Gatherers 'threatening, as I thought, to fall on me.' Eddie bought John's painting The Cornfield, now in the Tate. Much reproduced, it was one of Eddie's favourite purchases.

John Nash's The Cornfield is on display in #WWIAftermath, following the removal of old varnish from its surface. The work has been returned to its true nature (John didn't varnish his paintings) & has regained its colouring, crispness & depth of field.https://t.co/sEU1DNUOgH pic.twitter.com/ZmaW5gIVJD

— Tate (@Tate) June 5, 2018

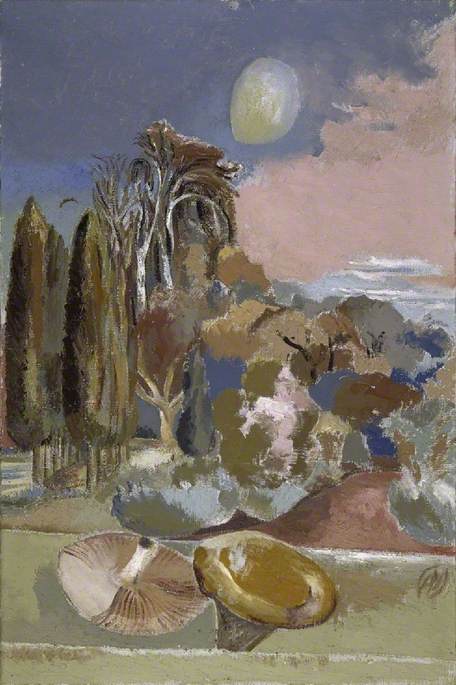

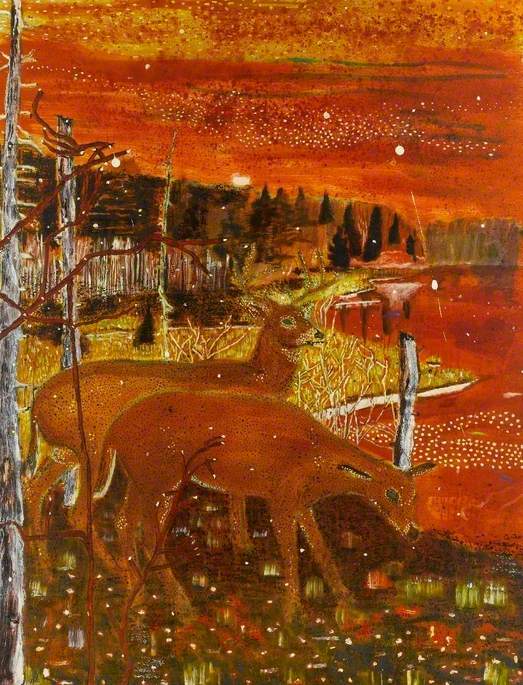

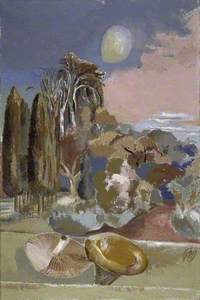

Marsh also bought at least 10 pictures from Paul Nash, who said: 'He was the first real collector I had met and I remember thinking to myself if all collectors collect in this way we shall all live happily ever afterwards.' The pair remained lifelong friends and when Eddie moved to his last flat in Chelsea, Paul Nash's November Moon, now in The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, had pride of place in his sitting room.

Eddie encouraged writers as well as painters, editing several anthologies of poetry and enjoying close relationships with Rupert Brooke, Siegfried Sassoon, D. H. Lawrence and many others. This, combined with his political and social connections, enabled him to introduce artists to other potential buyers.

From 1917 until his death he was a committee member of the Contemporary Art Society which he chaired from 1936 until 1952. The CAS continues to supply artworks to British galleries and museums. He was also a trustee of the Tate.

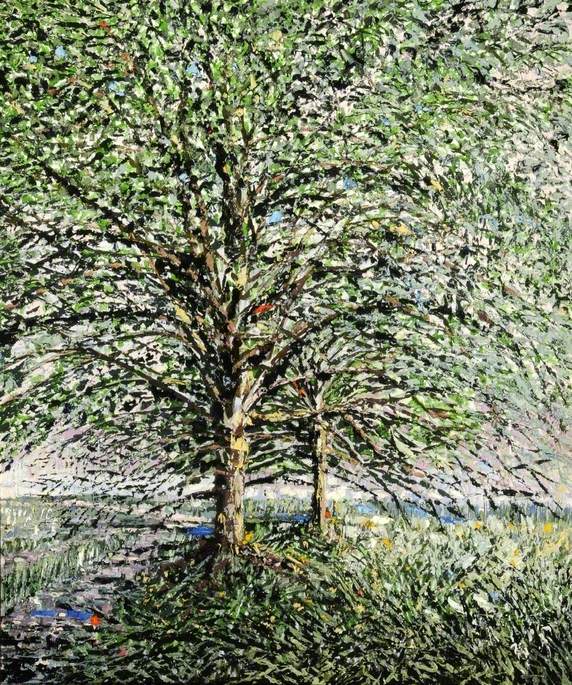

According to his biographer, Christopher Hassall, between the wars Marsh corresponded with 86 artists, about 30 of whom knew him as a regular visitor to their studios. He would ask artists he admired to recommend the work of others and took special delight in launching careers. Often, as was the case with Ivon Hitchens, he was the first to buy their work. The Miller's Cottage, now in the Alfred East Art Gallery in Kettering, was one of 250 pictures left to the CAS in his will – pictures which were later distributed to galleries across Britain.

In 1945 another of Marsh's protegés, Leonard Appelbee, encouraged him to become his neighbour in Chelsea where he painted a portrait of the 74-year-old collector. Marsh had bought from Appelbee's first exhibition in 1938 and now the younger man was helping him move into his last home.

'The rooms were small but I well remember hanging all but a few of his collection; there was no need for paint or wallpaper for no wall could be seen... I fully realise the debt owed to this man who encouraged so many young painters to find their way in spite of the jungle of the art world.'

Lovers of modern British art have reason to be grateful to him too.

James Trollope, author and columnist

James Trollope's book on another Marsh protegé, Rudolph Ihlee (1883–1968), will be published by Lund Humphries in 2022