In 1915, the leading British sculptor Sir George James Frampton (1860–1928) received a commission to create a public monument to commemorate the nurse Edith Cavell (1865–1915), an opportunity he took up so willingly that he waived the commission fee altogether.

Although Edith became a celebrity in Britain in the 1910s, her remarkable story is less familiar today.

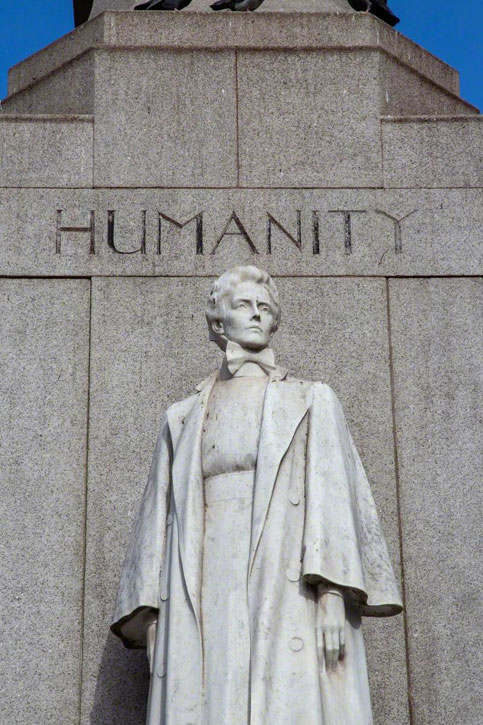

However, 17th March 2020 marks the centenary of the public unveiling of her Grade I listed stone memorial by Queen Alexandra in 1920, which can still be viewed today – standing a stone's throw away from Trafalgar Square in St Martin's Place. The monument bears her famous words:

'Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone.'

Edith Cavell (1865–1915)

1915–1920

George James Frampton (1860–1928)

Edith's story is equally shocking as it is courageous. On 12th October 1915, after tirelessly caring for hundreds of wounded British, Belgian and German soldiers, and helping Allied soldiers flee the brutalities of war in German-occupied Belgium, she was shot at dawn by German firing squad – despite international outcry for her release.

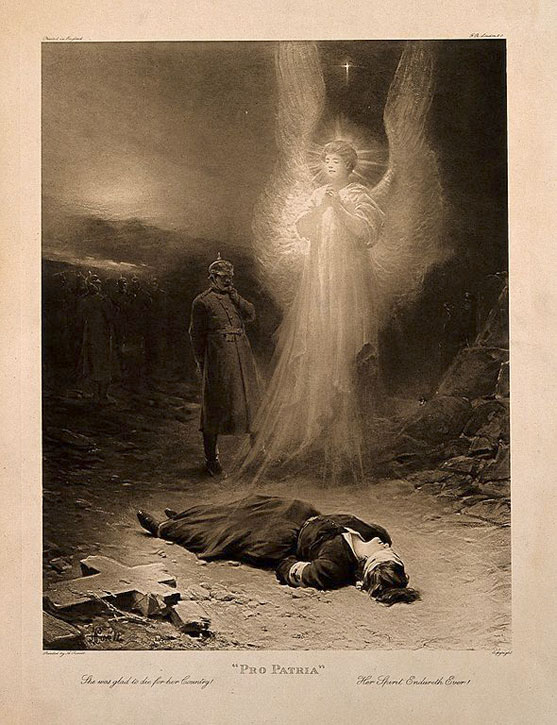

Her unjust death provoked further contempt towards the Germans across the world, and Edith quickly became a symbol of Allied resistance and a Christian martyr. Without discrimination, she had cared for wounded soldiers, regardless of their nationality.

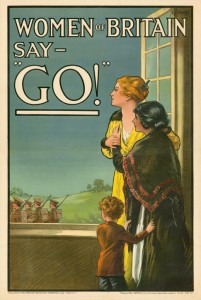

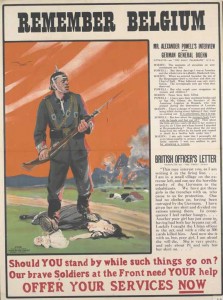

The British used her story as propaganda to recruit more soldiers and galvanise public opinion against Germany. Recruitment numbers in Britain rose from 5,000 to 10,000 a week after her death.

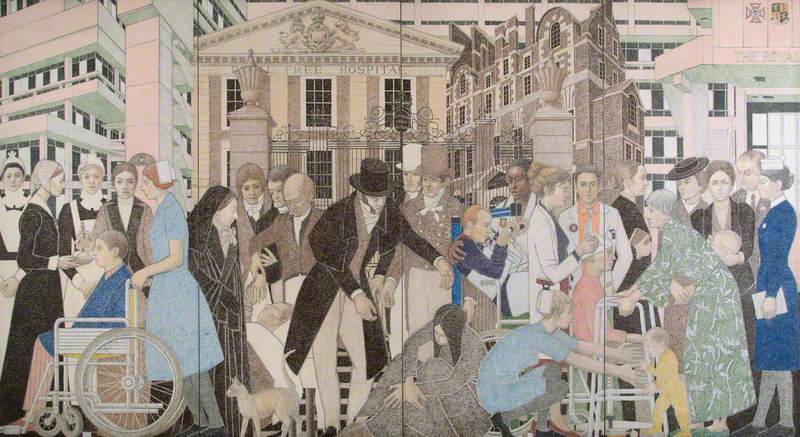

Born in the Norfolk village of Swardeston in 1865, Edith spent a great deal of her youth looking after her critically ill father, Frederick, the vicar of the local church. These formative experiences compelled her to train as a nurse at the Royal London Hospital by the time she turned 30. There, she trained under the supervision of the esteemed Matron Eva Luckes.

Nurse Edith Cavell 1865–1915

c.1865–1915, photograph showing Cavell (seated centre) among a group of her multinational student nurses whom she trained in Brussels, Imperial War Museums

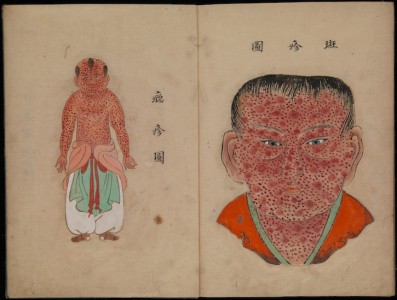

Not long into her training, she was placed on the front line of a typhoid outbreak in Maidstone – the largest ever reported in the UK. The medical staff responsible for containing the epidemic were so effective that Edith, alongside a dozen others, was awarded the Maidstone Medal. The survival rates were so high, that out of a total of 1,847 people who contracted the deadly disease, only 132 died.

Spread through contaminated water due to poor sanitation, typhoid was an incredibly common illness during the Victorian era in Britain – even Prince Albert died from the illness in 1861.

In 1907, Edith went to Brussels to nurse a sick child, having already spent five years working in Belgium as a governess between 1890 and 1895. While there she ended up running a secular training school for nurses, an unprecedented position as previously nuns were usually the only women allowed to work in infirmaries. In 1910, Edith began editing Europe's first nursing journals, called L’Infirmière ('nurse'). She was also in demand as an educator and lecturer.

At the outbreak of the First World War, after the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in June 1914, Edith was visiting her mother in Norwich – not long after the death of her father.

However, she felt her duty was to return to Brussels, where her clinic was declared 'neutral' and turned into a Red Cross facility. Edith was in Belgium when the German army invaded on 4th August. Although British and French civilians were ordered to return home, Edith remained to care for the wounded.

The Germans posted signs throughout the city threatening harsh penalties for anyone caught protecting or hiding enemy combatants. However, Edith fearlessly helped fugitives and prisoners of war to flee undetected. She did this over a period of nine months, saving the lives of approximately 200 Allied soldiers.

Edith Cavell, wearing Red Cross uniform, as her spirit rises in the form of an angel

c.1915, colour process print after painting by Alexander Rossell (1859–1922)

In August 1915, the Germans arrested her and she confessed to everything. She was found guilty of treason, specifically for providing 'reinforcements' to German enemies. However, historians today have argued that she may, indeed, have been recruited as a British spy.

At her two-day trial, she was charged with treason and sentenced to death by a German judge on 11th October 1915. Although legal under international law, it sparked great outrage in Allied and neutral countries. Historian Anne-Marie Hughes has argued that 'Cavell's gender and non-combatant status made her an exceptionally good candidate for use in propaganda because it was more plausible to portray her as a victim and appeal to men's chivalrous urges.'

Cavell told English chaplain Stirling Gahan that she was not afraid and had no regrets about her actions or sentence. Gahan noted that she was incredibly calm despite her fate, and he recorded her saying: 'I have no fear nor shrinking; I have seen death so often that it is not strange or fearful to me... Patriotism is not enough. It is not enough to love one's own people, one must love all men and hate none.'

Edith's state funeral took place at Westminster Abbey on 15th May 1919, and was attended by thousands. The words of Edward VII's widow, Queen Alexandra, were read to the congregation:

'In memory of our brave, heroic, never-to-be-forgotten Miss Cavell. Life's race well run, life's work well done. Life's crown well won, now comes rest. From Alexandra.'

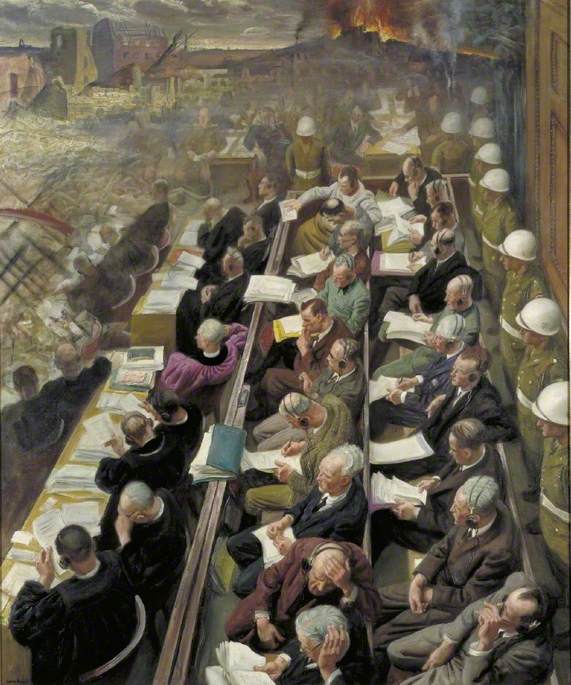

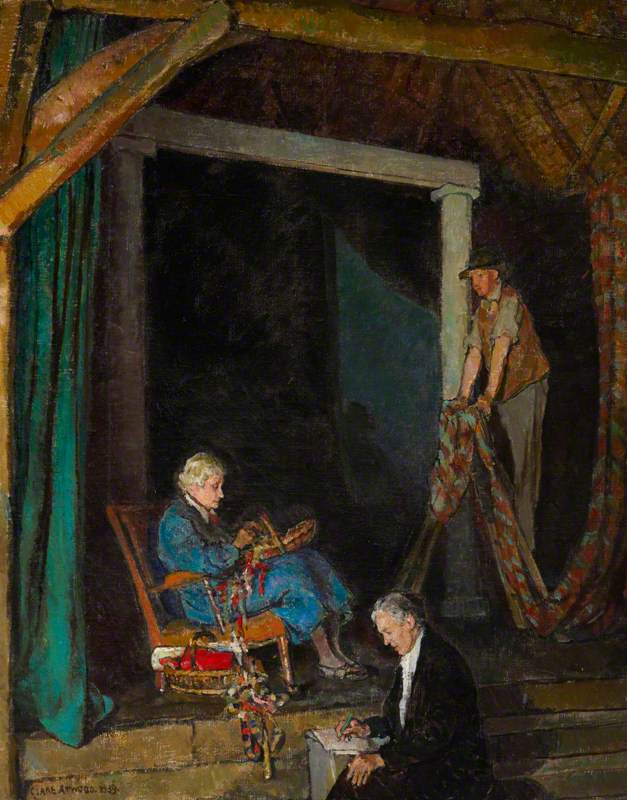

Artist William Hatherell (1855–1928) was commissioned to paint the event.

The Funeral Service of Edith Cavell at Westminster Abbey, 15 May 1919

1919

William Hatherell (1855–1928)

One year later, photographer Reginald Silk captured the unveiling of Frampton's statue in 1920. At this time, Frampton was President of the Royal Society of British Sculptors and regarded as one of the most important sculptors in Britain. He had been a key figure in the late-nineteenth-century New Sculpture movement and his other famous works included the statue of Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, and the lions at the British Museum.

The unveiling of George Frampton's statue of Edith Cavell

1920, bromide press print by Reginald Silk (active early 20th century)

The modernist 10-feet high monument further cemented Edith Cavell's legacy in granite and white marble. Despite this, it was poorly received by many of Frampton's contemporaries who criticised the poor engineering of the statue. The words 'fortitude', 'sacrifice' and 'humanity' are engraved onto the plinth beneath the lifelike statue of Cavell, who stands in her nurse's uniform in calm defiance.

The unveiling of George Frampton's statue of Edith Cavell

1920, bromide press print by Reginald Silk (active early 20th century)

In 1922, the National Council of Women of Great Britain and Ireland proposed to have the nurse's reported words 'patriotism is not enough' added to the memorial.

Edith's remarkable story extended beyond Britain. Sculpted monuments dedicated to her can also be found in Paris' Jardin des Tuileries by Gabriel Pech, and in Brussels by Paul Du Bois. In 1916, a mountain in Canada was named after her.

Still today, the charitable Cavell Nurses' Trust which was founded in her memory in 1917 supports the welfare of nurses, midwives and healthcare assistants in the UK.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Further reading

The Victorian Web, 'Edith Cavell', Sir George Frampton, RA (1860–1928), 2009

Anne-Marie Claire Hughes, 'War, Gender and National Mourning: The Significance of the Death and Commemoration of Edith Cavell in Britain', European Review of History, Volume 12, Issue 3, 2005