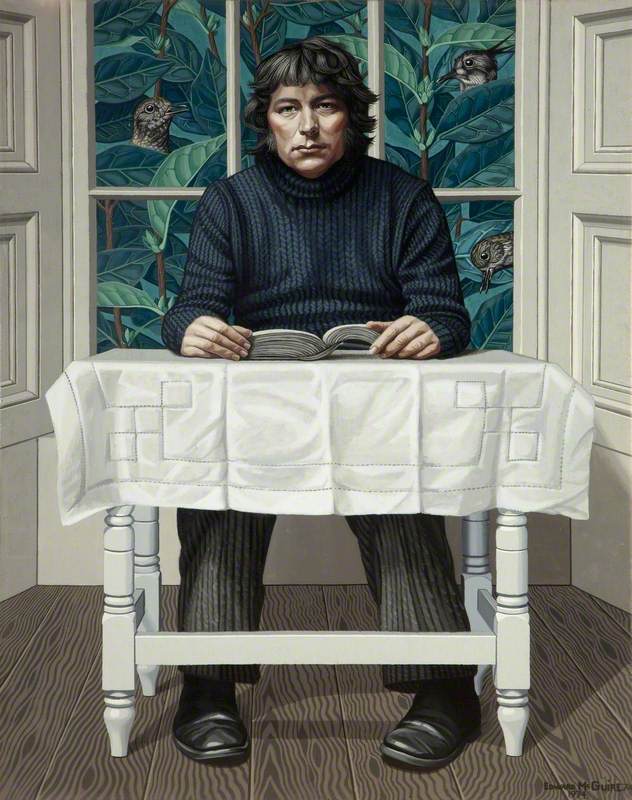

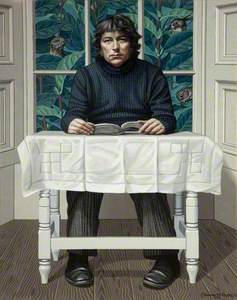

What is often – though not always – expected of portraits, is that they capture the likeness of the portrayed individual. At first glance, this painting by Edward McGuire seems to do precisely that. Looking at the image, the viewer’s eyes are immediately drawn towards the brightly lit face which is easily

By painting Heaney holding a book, McGuire is clearly making a direct reference to the sitter’s professional calling. At the time when the portrait was painted, Heaney had already published three books and was on a clear path to success. Still, by choosing this particular setting where the book is rested, the painter further comments on what the profession means to the poet without the need for words. The table is set with a clean tablecloth laid down on its surface, but there is no food being served, perhaps

By incorporating blackbirds into the painting, McGuire highlights the importance of Northern Ireland and its nature on Heaney’s personal life and poetic inspiration.

The nature theme of plants and birds which runs across the background deserves special attention. At first, McGuire’s hyperrealistic style can trick viewers into perceiving the backdrop setting as nothing but a documentation of the surrounding environment where the portrait was conceived. However, the scenery is so idealistically painted that it becomes doubtful that a realistic representation is

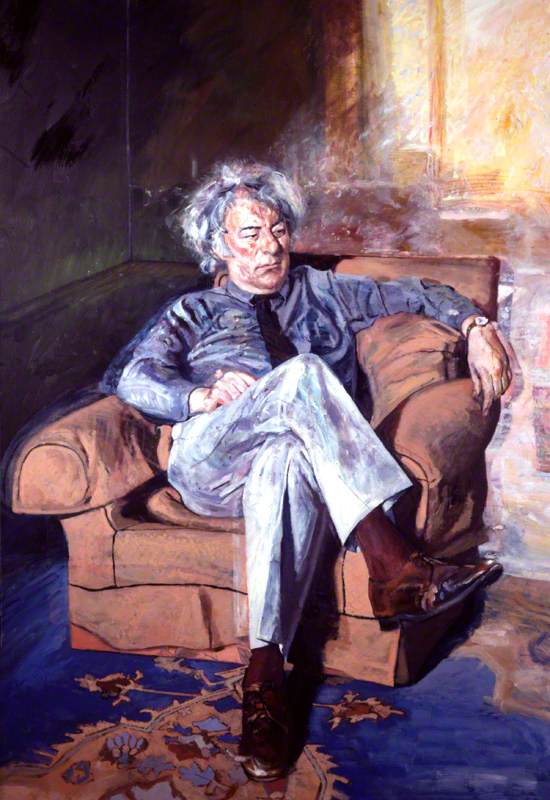

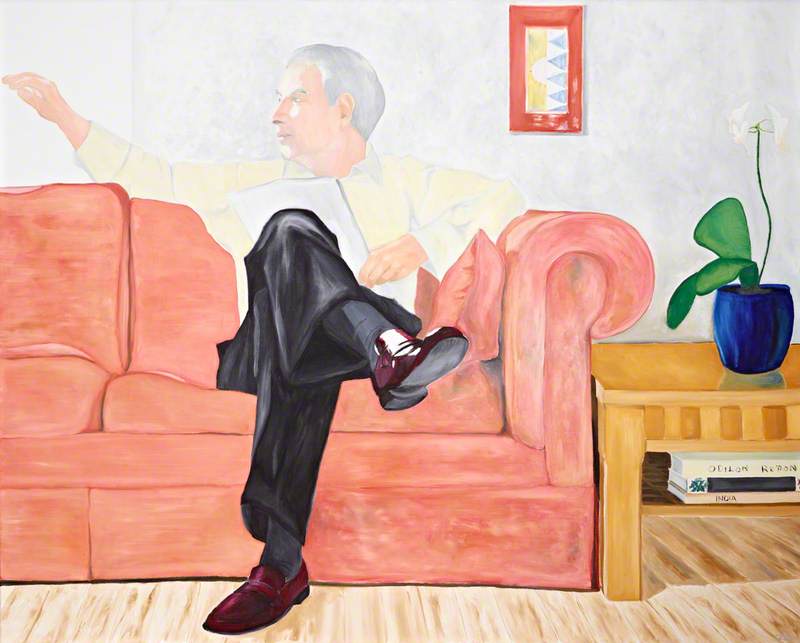

This is especially evident if one considers Peter Edwards' portrait of Seamus Heaney (1955). The painting by Edwards is bare of any unnecessary embellishments, maintaining the focus on the sitter who is presented as if engaged in deep contemplation.

From the

‘[...] At dusk, horizons drink down sea and hill,

The

And you’re in the dark again. Now recall

The glazed foreshore and silhouetted log.

That rock where breakers shredded into rags,

The leggy birds stilted on their own legs,

Islands riding themselves out into the fog. [...]’

Furthermore, the depiction of young blackbirds in the painting parallels Heaney’s work which

As a confirmation of this, the blackbird in the background of a painting from his early years became central in a poem published over thirty years later, after countless achievements – including winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995. ‘The Blackbird of Glanmore’ is the last poem in his last book District and Circle (2006) which earned him the prestigious T. S. Eliot prize:

‘On the grass when I arrive,

Filling the stillness with life,

But ready to scare off

At the very first wrong move.

In the ivy when I leave.

It’s you, blackbird, I love. [...]’

Whether the painter intended everything precisely as described in this short analysis is perhaps

Stefani Bednarova