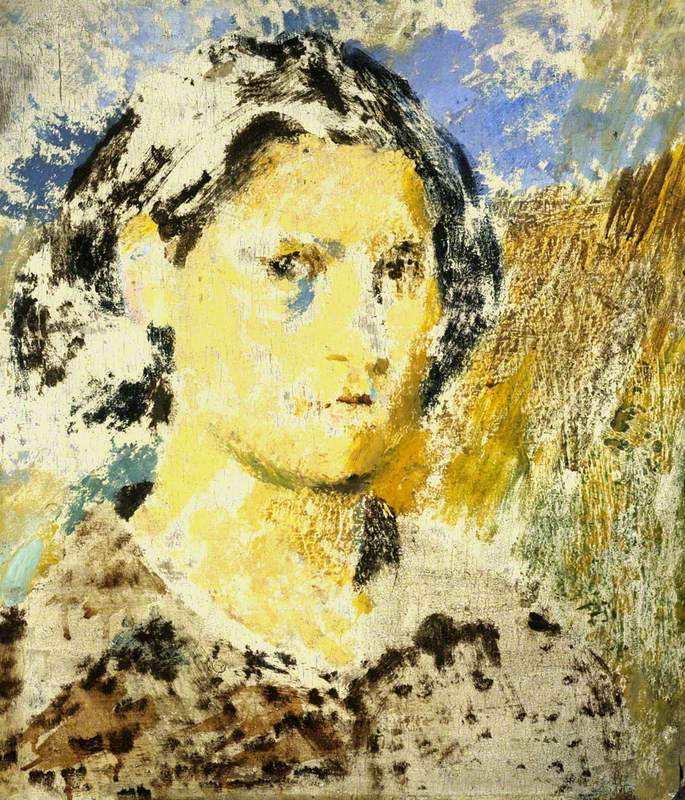

While studying at the University of Cambridge in summer 2012, I happened upon the archives and paintings of Elisabeth Vellacott at Kettle’s Yard.

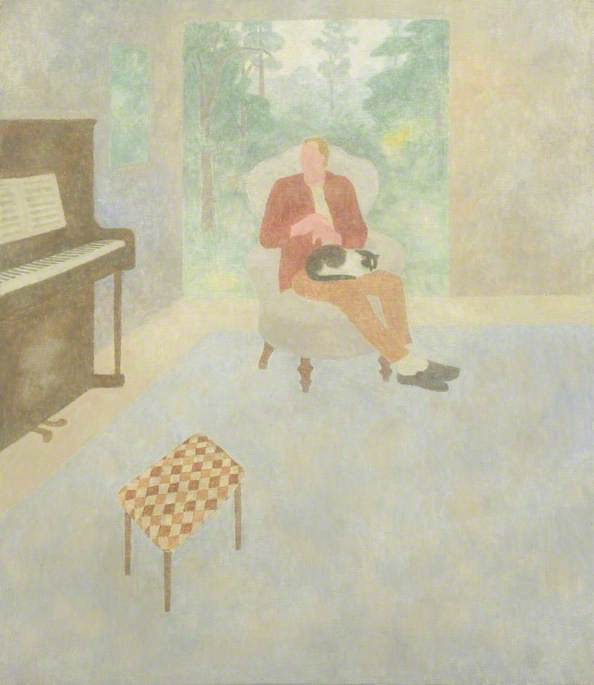

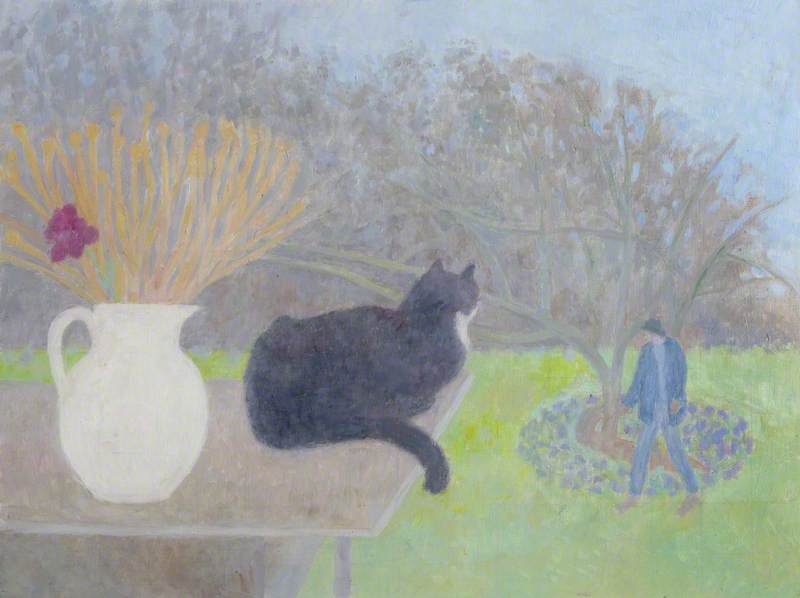

'Lulu', Jug and an Apple Tree

c.1995

Elisabeth Vellacott (1905–2002)

Though relatively unknown, she was a central aesthetic and personal force in the Cambridgeshire community until her death in 2002.

It is no mistake that Sir Nicholas Serota, the former Director of the Tate, is an admirer of her evocative and prolific career: ‘We at Tate regard Elisabeth Vellacott as a significant painter whose work deserves to be seen in the context of the best British art of the twentieth century. Hers is a quiet but insistent voice and her works have real quality, even if they are not fashionable on the market.’*

It is doubtless time to hear this voice, and when we listen to it, we have the opportunity to rethink whose stories comprise art historical narratives.

Vellacott, born in Grays, Essex in 1905, attended the Royal College of Art in 1925 – a decision that drew scrutiny from her friends and family because of her gender. Some saw her passion as a useless and selfish profession that had no relevance in hard times. Nonetheless, in 1926, she returned to her family’s new residence in Cambridge, and, despite the criticism, created a studio in Ram Yard. At this time, Vellacott was also involved in set design for the Cambridge University Music Society and the Old Vic.

In the Second World War, a bomb raid destroyed her studio and most of her early works. She finally settled in an A-framed house at Hemingford Grey in Cambridgeshire – her beloved home for the rest of her life.

From the start, Vellacott was caged in by gender biases and analytical oversights. In her first large scale show in 1968, the curators characterised her work as a vapid hobby for an aging woman, and her name was even misspelled on the cover of the exhibition catalogue. Even in recent times, many critics attribute Vellacott’s presence in the art scene to the help of men, as if her status as a middle-class woman precluded her from achieving a modest amount of success on her own in the pantheon of modernism.

It follows that most of the writing on her career focuses unduly on feminine stereotypes, such as domestic life, crafts, and decoration, leading ultimately to a monolithic understanding of her multifaceted artistic production. It appears that from early on until the present day, the force of gendered readings propelled a definite underestimation of the power of her collected works, especially her paintings.

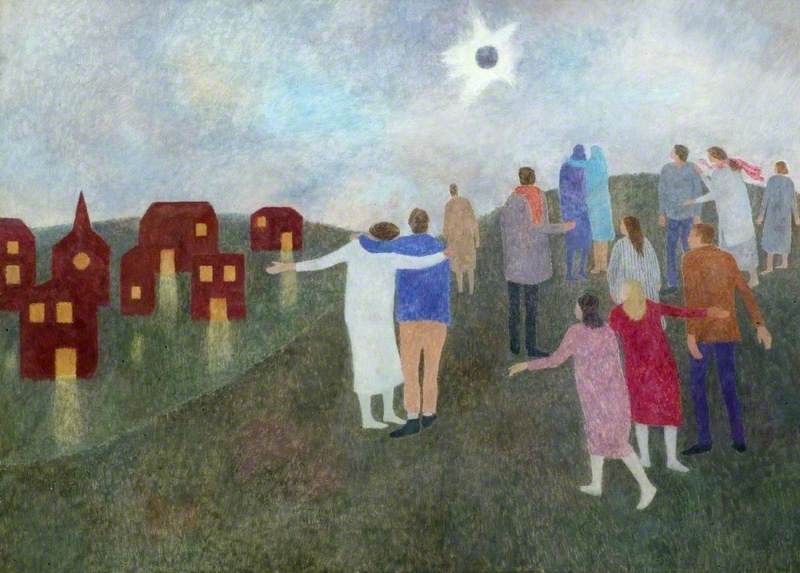

Vellacott’s marginalisation, however, did not hinder her from creating revolutionary, critical artworks that point to the insecurity of the stereotypes that followed her without respite.

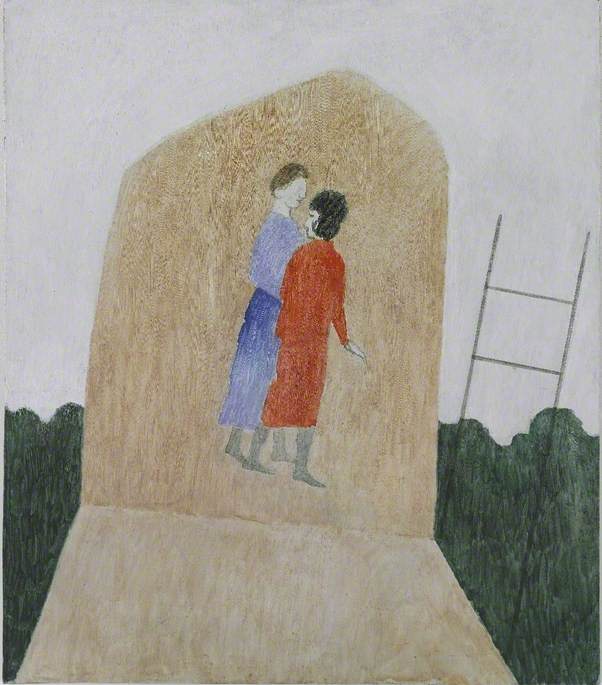

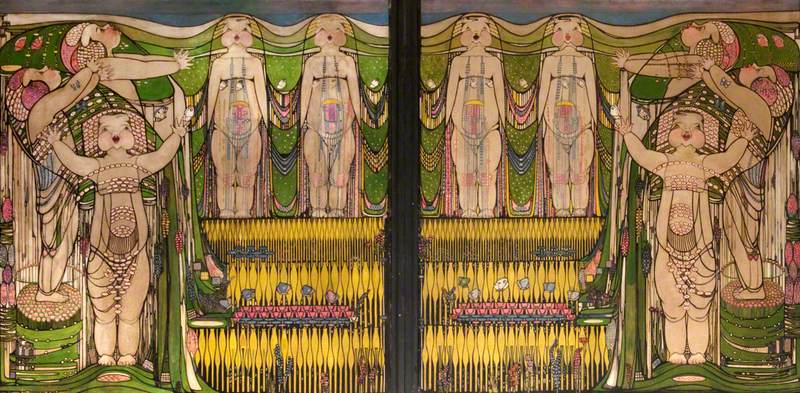

Consider, for example, the undated Garden Painting, in which the skewed perspective and unsure relationships among the figures create an indeterminate space that defies any singular reading.

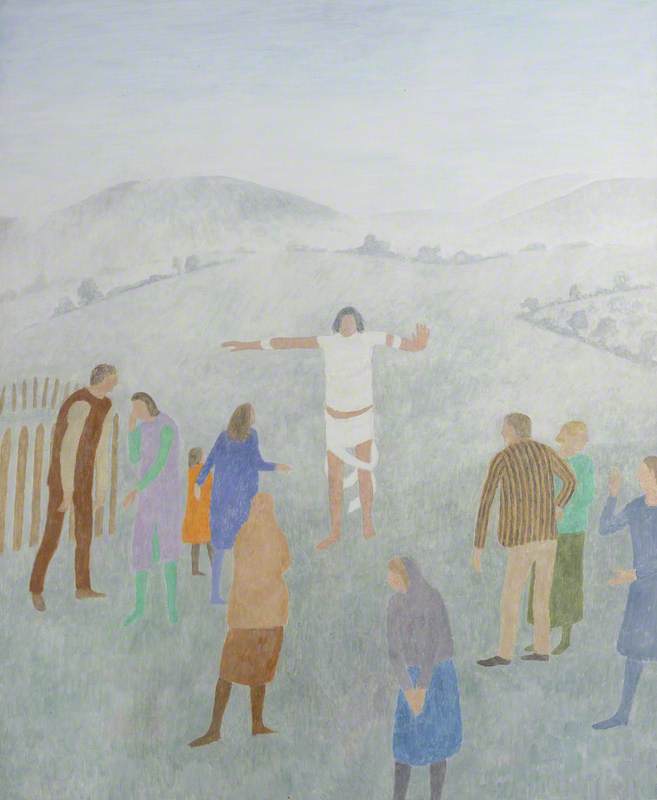

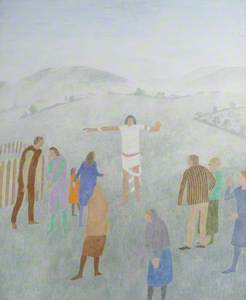

Similarly, in Lazarus from 1975, the eponymous central character emerges from a nonexistent tomb, only to be greeted with ambivalence by a scattered crowd in modern dress.

Vellacott leaves us with more questions than answers, and, in so doing, defies both the conventions of gender and traditional conceptions of British modernism.

William J. Simmons, critic and a PhD student in art history and women's studies at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York

This article is in part an excerpt from a talk, Elisabeth Vellacott, Kettle’s Yard, and the Politics of Gender

*Personal communication via email, 12th August 2012