In 1929 a relatively obscure Sussex printmaker produced this image of waves crashing against the cliffs at Seaford Head in East Sussex.

Rough Sea

1929, colour woodcut by Eric Slater (1896–1963)

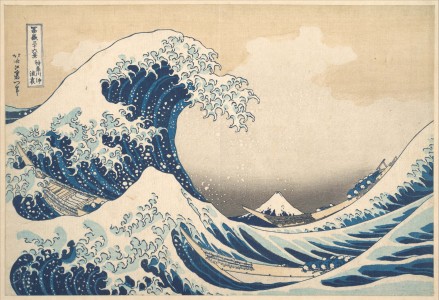

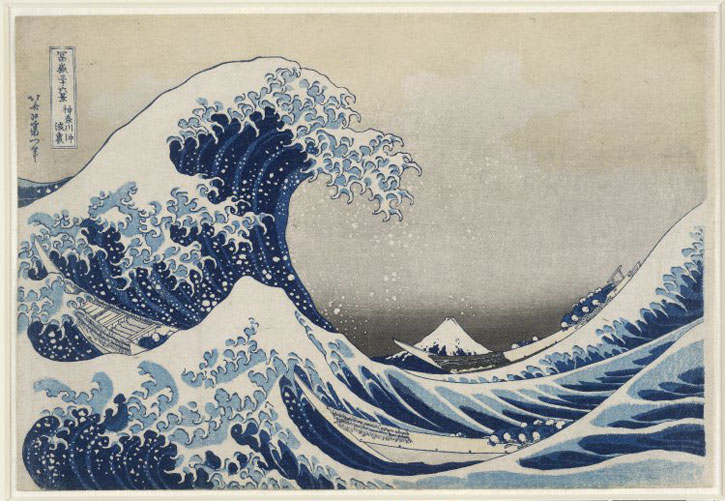

Eric Slater (1896–1963) was one of a select band of British artists who had mastered an oriental method of colour printmaking of which Hokusai's The Great Wave is the supreme example.

The Great Wave

'Under the Wave off Kanagawa' from the series 'Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji', 1831, colour woodblock oban print by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Curiously, in one sense, Slater went one better than Hokusai (1760–1849). For although Hokusai designed The Great Wave, he relied on highly trained craftsmen to carve and print the woodcut. As these skills were lacking in the west, Slater had to learn the process himself.

Between the wars, Slater made around 40 woodcuts of Sussex, taking inspiration from the landscape around his home in Seaford where he lived for more than 30 years.

Seaford Head

1930, colour woodcut by Eric Slater (1896–1963)

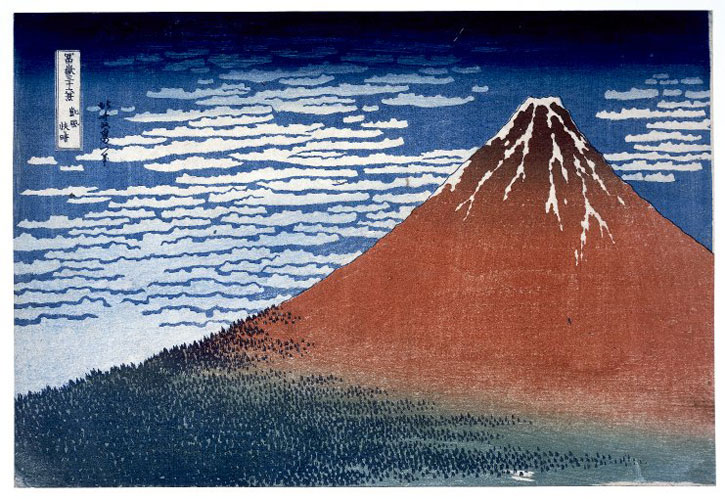

Hokusai produced his best-known series of landscapes, Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji, a hundred years earlier when he was around 70.

Red Fuji

'Clear Day with a Southern Breeze' from the series 'Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji', 1831, colour woodblock oban print by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

Although the two artists were working a century apart, there are similarities in their subject matter as well as the method by which the prints were made.

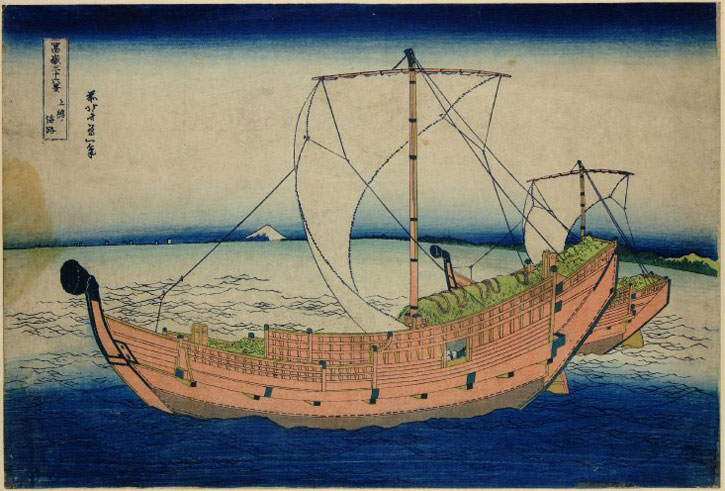

Sea Lane off Kazusa Province

From the series 'Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji', 1830, colour woodblock oban print by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

While Hokusai's fishing boat is off Kazusa province, Slater's is at the Sussex port of Newhaven.

Morning Calm, Newhaven

c.1935, colour woodcut by Eric Slater (1896–1963)

Ports in Japan had been closed to the west since the seventeenth century, with the exception of Nagasaki where there was limited trade with the Dutch. It was not until the second half of the nineteenth century, after Hokusai's death, that the country emerged from isolation. Ideas were traded as well as goods and the composition of Japanese prints influenced many leading western artists such as Monet and Van Gogh.

Most, though, didn’t attempt to learn the method by which the prints were made. That challenge was taken up by a group of less well-known British artists, led by a teacher called Frank Morley Fletcher (1866–1949).

Fletcher learned the process from a Japanese manual and produced his first solo print in 1897. In 1916, he wrote his own handbook called Woodblock Printing: A Description of the Craft of Woodcutting and Colour Printing based on the Japanese Practice.

Many learned the craft from Fletcher's book, which describes how to cut a block for each individual colour by gouging a trench to leave a raised shape; how to apply watercolour and rice paste to these raised surfaces; and how to make a print by passing the same sheet of paper over each separate block to create the finished image.

Arthur Rigden Read (1879–1955) was one of many to have learned the technique entirely from Fletcher's manual. And he passed on his knowledge to his younger Sussex neighbour – Eric Slater.

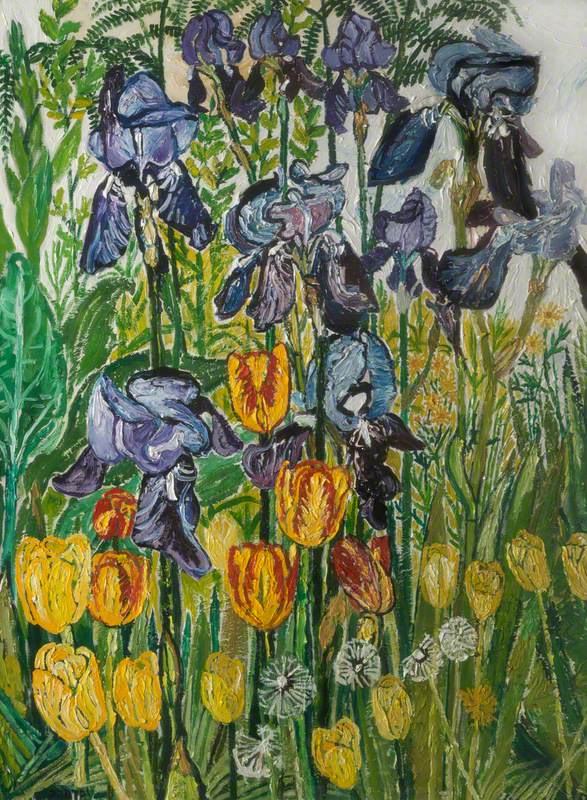

While Hokusai's prints were often produced in their thousands by teams of craftsmen working to his designs, British colour woodcut artists, usually working alone, tended to produce editions of around 50. And although their technique was Japanese in origin, the images were mostly in the western tradition with flowers a popular subject.

Although much less well known than his landscapes, Hokusai also produced several floral works.

Lillies

1831–1832, woodblock print by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

British colour woodcuts were popular home decoration between the wars when there was a surge in house building.

During this period about a hundred British artists – men and women – exhibited woodcuts regularly with the Society of Graver Printers in Colour which held annual shows in London.

The popularity of the British colour woodcuts faded after the Second World War and they have since been overshadowed by the modernist linocuts which emerged from the Grosvenor school in the 1920s and 1930s.

Coastguard Station

1930, colour woodcut by Eric Slater (1896–1963)

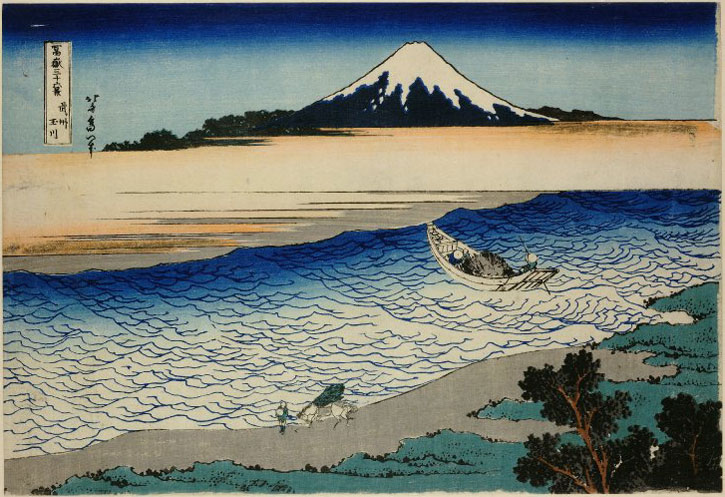

The Tama River in Musashi Province

From the series 'Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji', c.1830, colour woodblock print by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849)

In recent years, however, Eric Slater's woodcuts have attracted a growing following. Their distinctive portrayal of the Sussex countryside owe a debt not only to Hokusai but the unsung craftsmen who carved and printed his designs.

James Trollope, author and columnist