A contemporary of Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach, Eva Frankfurther may not be as famous, but her legacy is just as powerful.

Instead of pursuing fame and fortune, the German émigré artist moved to a damp basement flat in Whitechapel and chose to make figurative sketches and paintings of her fellow workers and residents. Yet through her work, Frankfurther created a unique snapshot of London’s rapidly evolving East End and its changing identity.

Now, Ben Uri Gallery & Museum is shining new light on Frankfurther, with a website dedicated to showcasing some 550 of her sketches, paintings and drawings and an exhibition of her work.

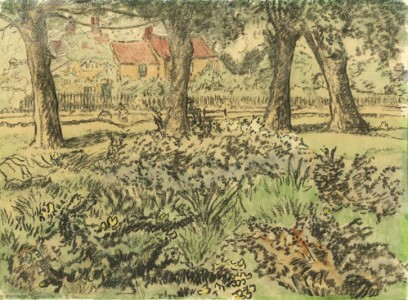

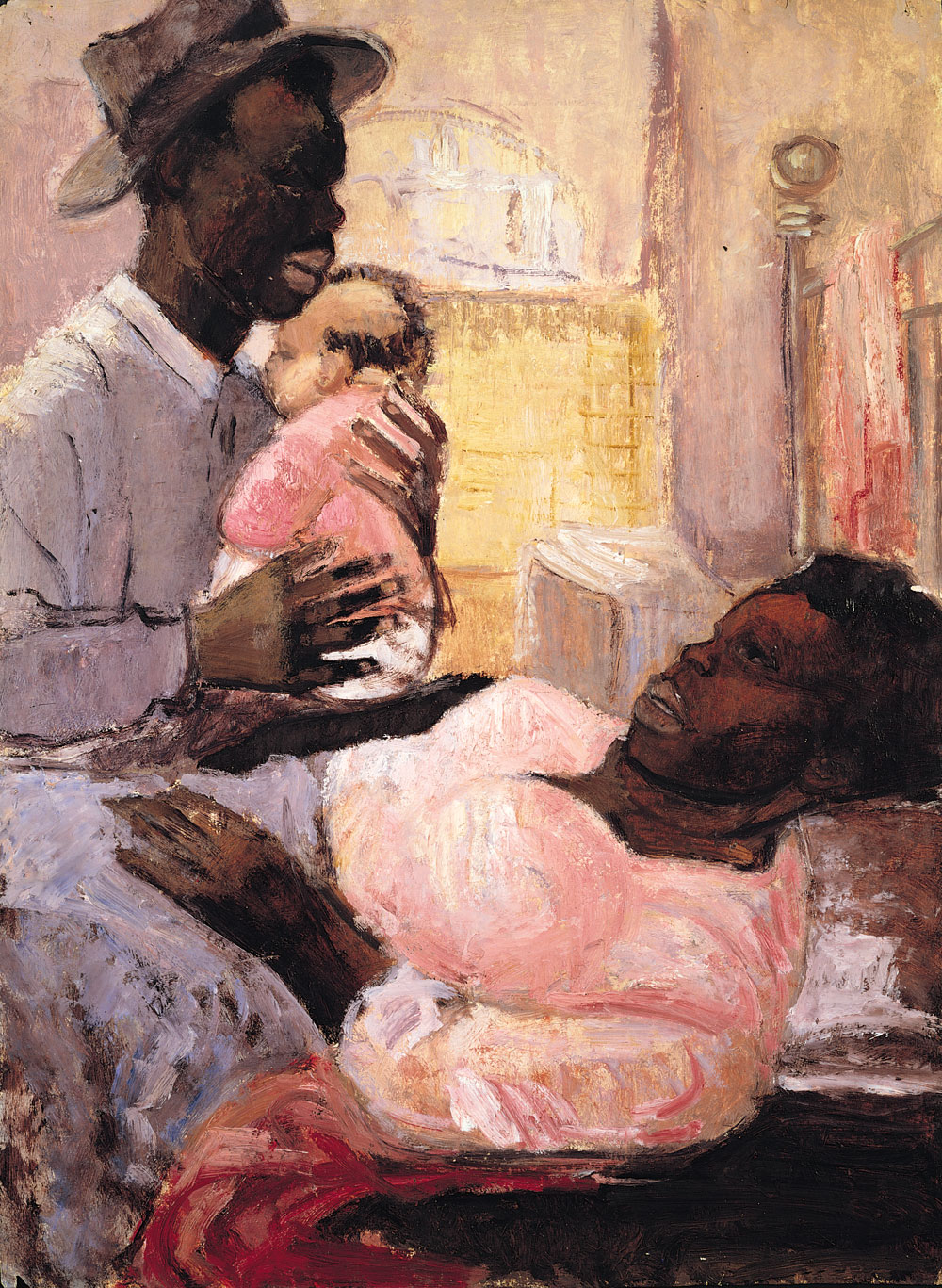

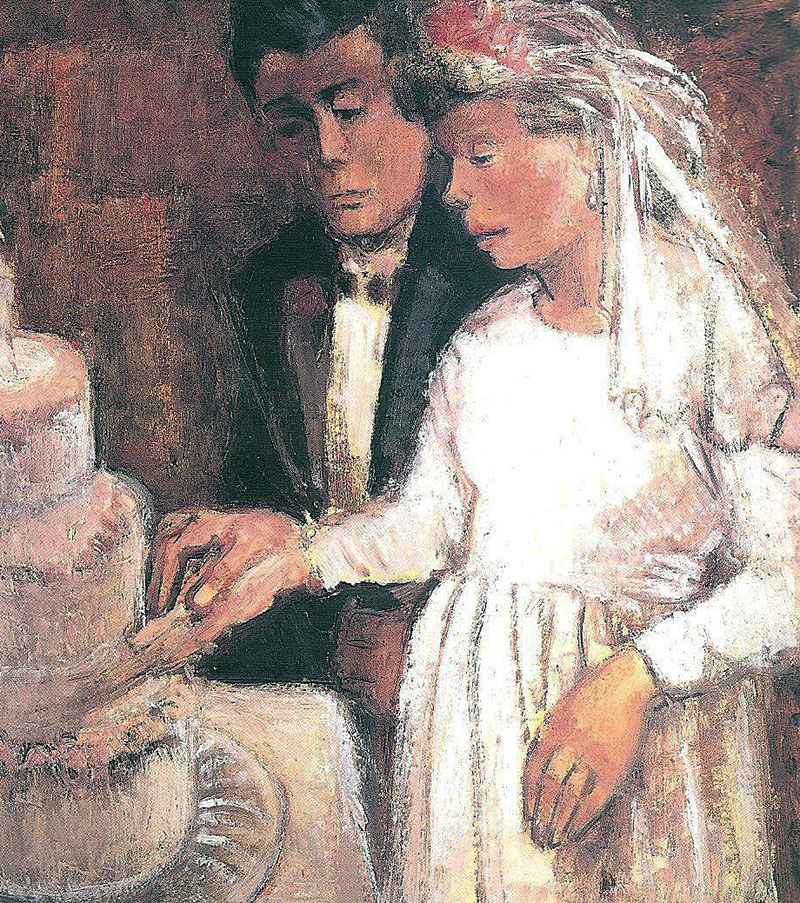

To browse through Frankfurther’s work is to take a walk (primarily) through Whitechapel in the 1950s, experiencing all facets of life in multicultural, postwar London. The East End had been heavily bombed and was still recovering, as were its residents. Old men, mothers and children, West Indian waitresses, brides, flower sellers, street children: the quantity and the variety is breathtaking. None of the subjects look directly at the viewer: they’re engaged in their own lives, making do in a recovering Britain. Characters from Jewish life are well represented – cloth merchants, Rabbis, Jewish bakers, kosher butchers – but by the 1950s the East End was moving on and was no longer a predominantly Jewish area, becoming home to a truly mixed population including West Indian, Pakistani and Irish communities.

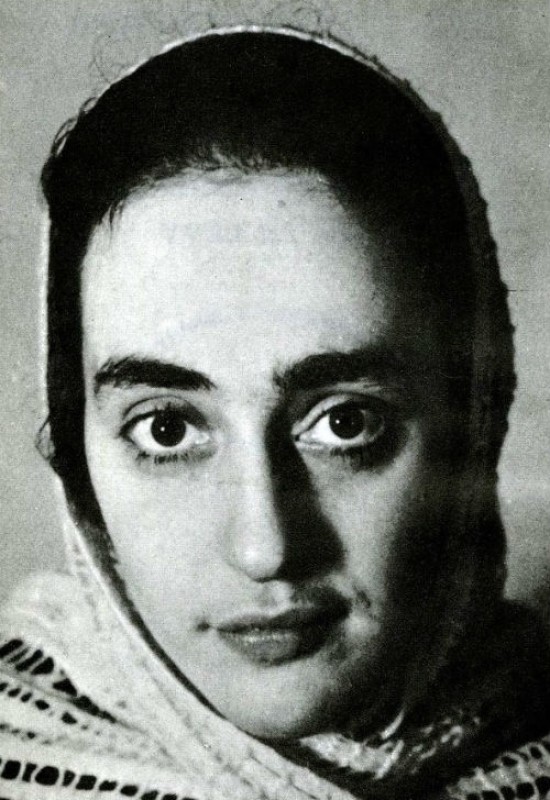

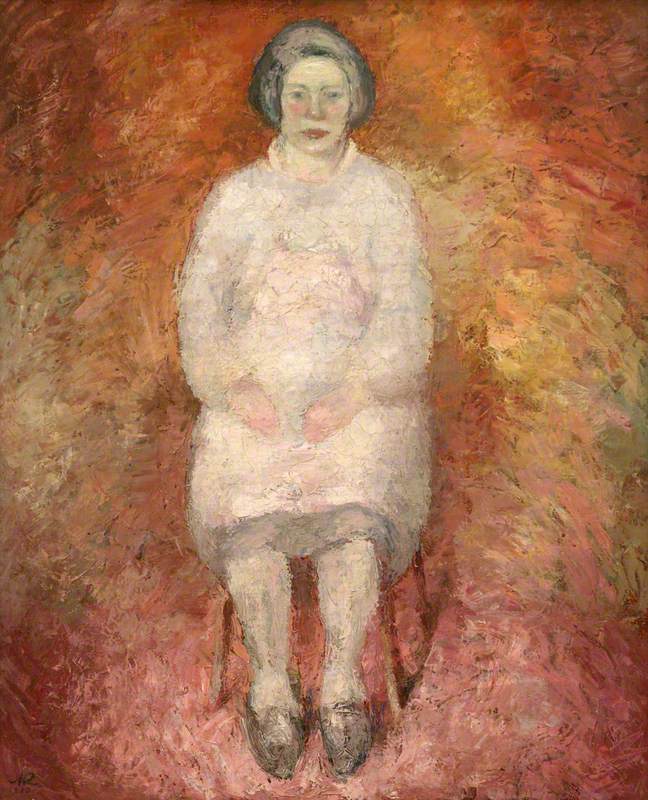

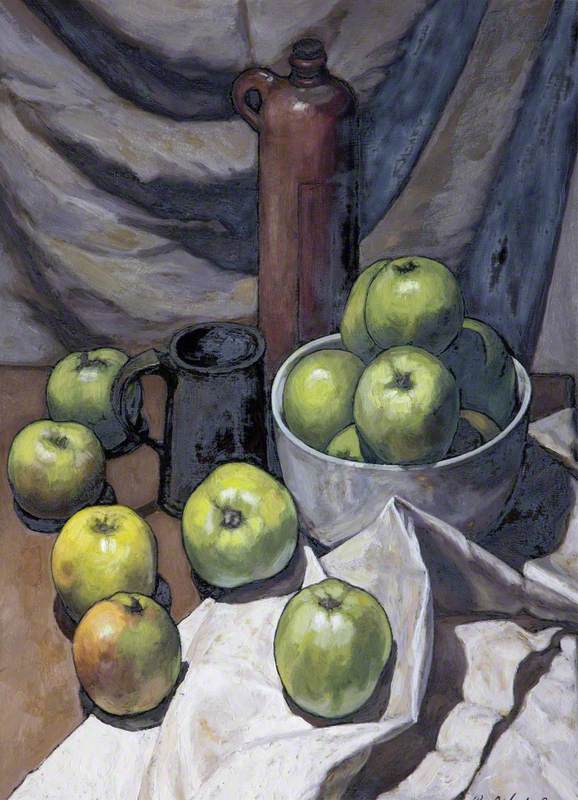

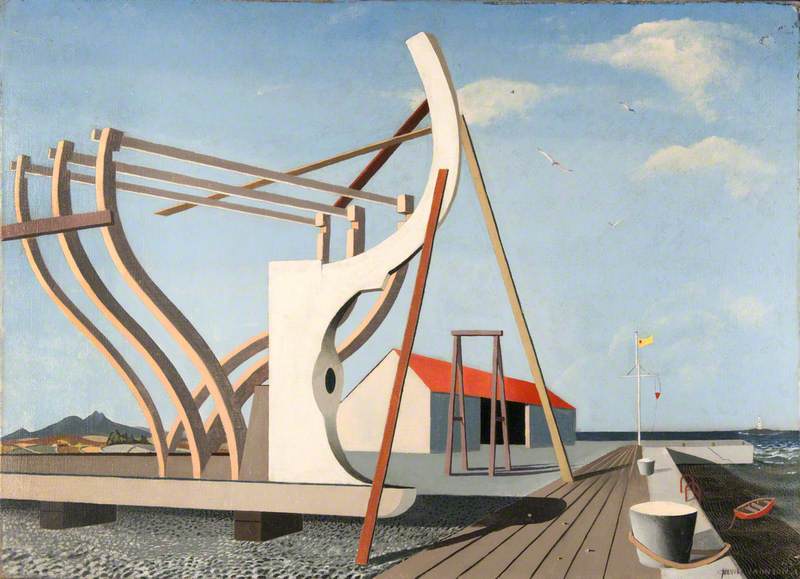

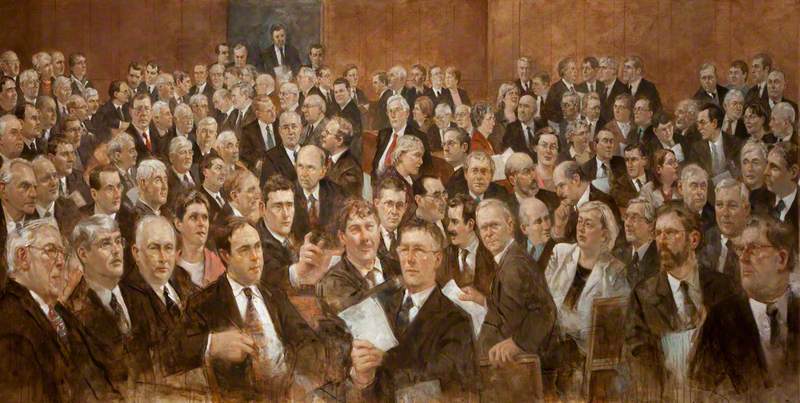

© the artist's estate. Image credit: Micky Slingsby

Couple with Infant

Eva Frankfurther (1930–1959)

Frankfurther was born in Berlin in 1930, and so her childhood was – unavoidably – shadowed by the rise of National Socialism. Her family fled to England in 1939, and after being evacuated out to Hertfordshire during the Blitz, Frankfurther was eventually able to move back and later attend St Martin’s School of Art, alongside Leon Kossoff and fellow refugee Frank Auerbach, the latter of whom described her work as ‘full of feeling for people’ and contemptuous of ‘professional tricks or gloss’. Frankfurther said of her own work:

...my colleagues and teachers were painters concerned with form and colour, while to me these were only means to an end – the understanding of and commenting on people.

Indeed, Frankfurther’s own disrupted childhood and status as an outsider seemed to inform her desire to represent the stories of others: akin to Joan Eardley in Glasgow, a social conscience shines through in her work. She seemed to draw influence from everywhere she went – as Sarah MacDougall, the new exhibition’s curator, describes:

‘After leaving St Martin’s, Frankfurther embarked on her first visit to Italy… there she painted pilgrims, beggars and children: and on her way home stopping off in Paris sought local colour in the working-class districts. On an earlier trip to the United States, she had made a point of visiting the black-American population of Harlem, laying the foundation for her interest in depicting ethnic minorities’.

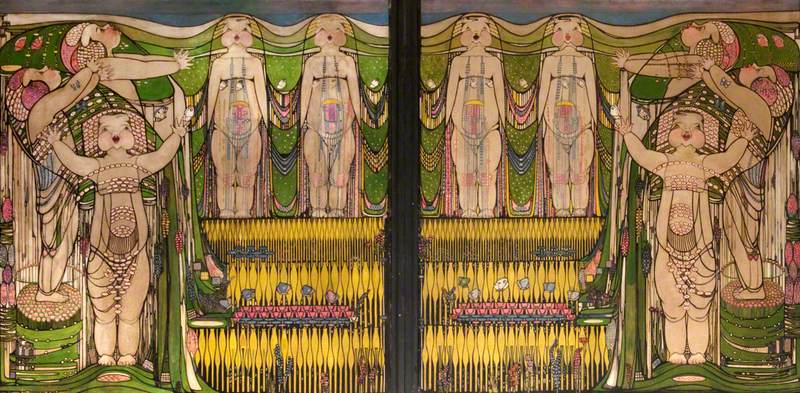

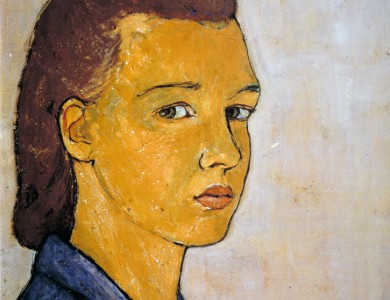

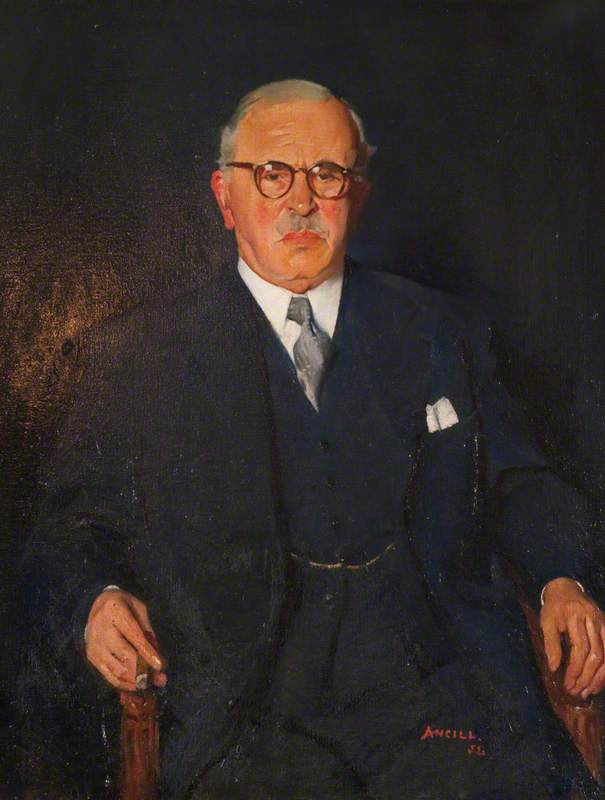

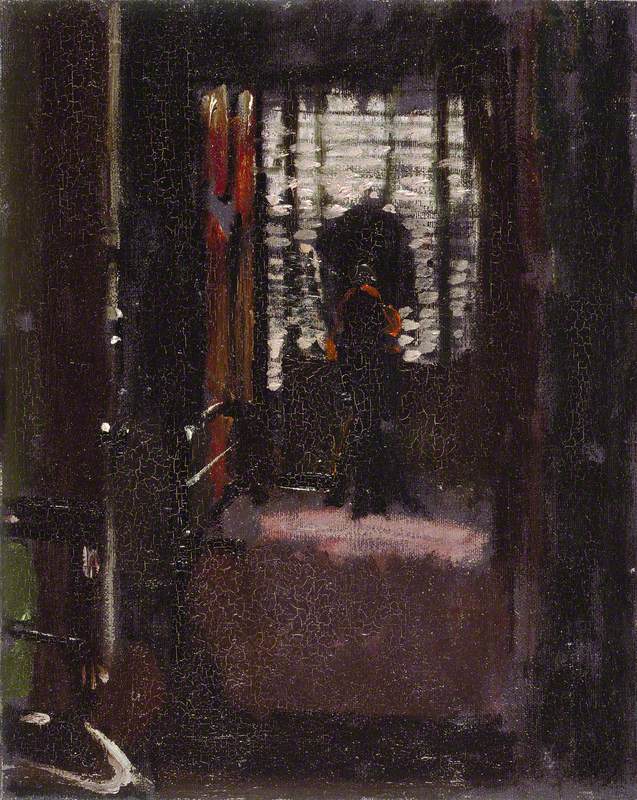

© the artist's estate. Image credit: Micky Slingsby

Orthodox Jew, Whitechapel

Eva Frankfurther (1930–1959)

Subsequently, Frankfurther showed little interest in the London art scene she could have been a part of. Her style never became experimental or flashy: she focused relentlessly on portraying her subjects, seeming to care more about representing their inner lives than paying meticulous attention to their outer features. She left behind a comfortable family home in Hampstead to move to the basement flat in Whitechapel that she’d call home, working in Lyons Corner House every evening (and closely observing her fellow workers), and painting obsessively by day. She exhibited – and sold work – in local exhibitions but never signed her works, and often gave paintings away to family and friends. She physically took herself out of reach of a mainstream artistic audience and was not surrounded by a network of fellow artists: all of which means she isn’t often remembered in the same breath as some of her contemporaries.

Tragically, Frankfurther took her own life aged just 29, which makes her large body of work all the more impressive. Sarah MacDougall sums up her contribution to the art world: ‘Upon her death Frankfurther left not only a collection comprising over 200 paintings, a handful of etchings and numerous drawings, but a portrait of the decade of austerity through which she lived and of the people of the old and new communities who inhabited it. Her instinctive sympathy for workers, immigrants and other people on the margins was probably due at least in part to her own experience as a German-Jewish exile and an outsider, but also allowed her a remarkable insight into their inner lives, in which she revealed herself to be above all an artist of "vision and compassion".'

Ben Uri Gallery and Museum’s new site gives us all amazing access to the works of this underrepresented artist: examine, explore and immerse yourself in the East End of times gone by.

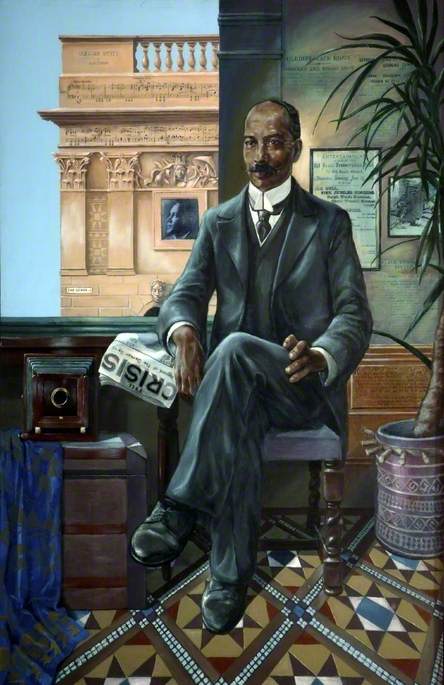

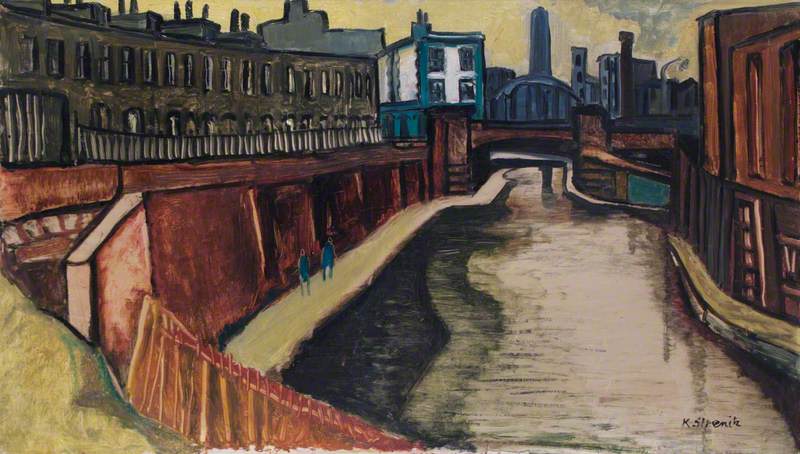

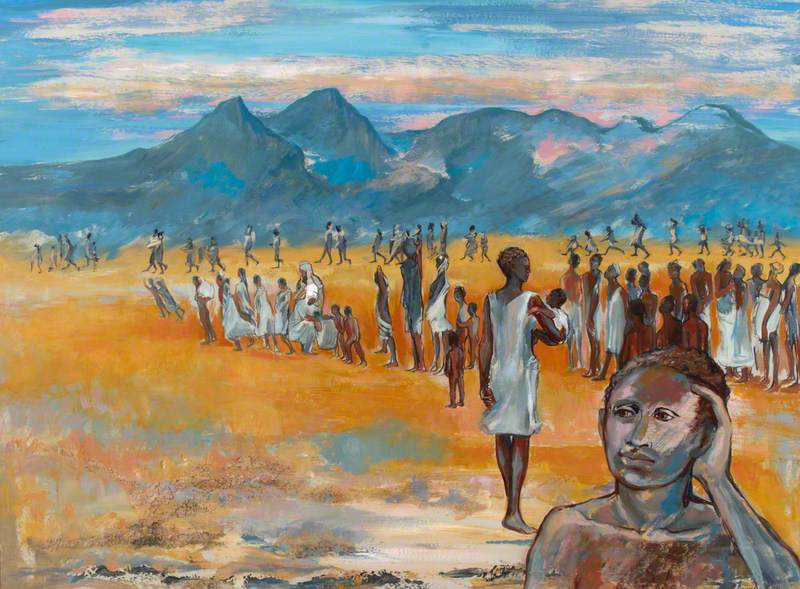

© the artist's estate. Image credit: Micky Slingsby

For Better For Worse

Eva Frankfurther (1930–1959)

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer

‘Selected Works by Eva Frankfurther’ was on at Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, Upper Gallery, 29th March – 18th June 2017.

‘The Lives of Others’ explores artworks and archival material by an array of both celebrated and lesser-known German-born refugee artists and was on at Ben Uri Gallery & Museum, Lower Galleries, 29th March – 4th June 2017.