Who should be depicted in a hall of fame and who should choose?

These questions are at the heart of a new curated display at Watts Gallery, 'Faces of Fame: GF Watts X Simon Frederick', which brings together two 'hall of fame' portrait series – one historic, one contemporary – to address themes of identity, representation and definitions of 'greatness'. Both series were gifted by the artists to the National Portrait Gallery and have been loaned to the Watts Gallery to be displayed together for the first time.

Installation view of 'Faces of Fame' at the Watts Gallery

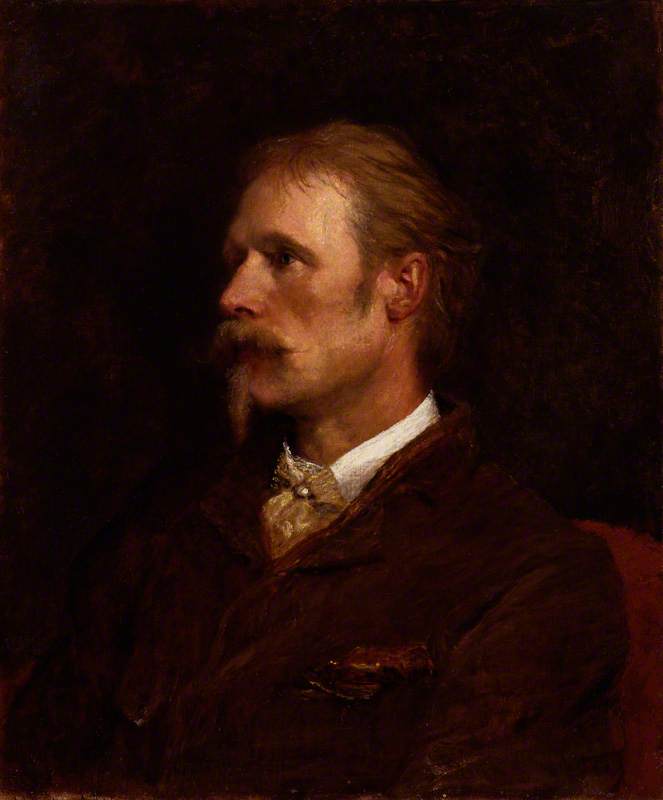

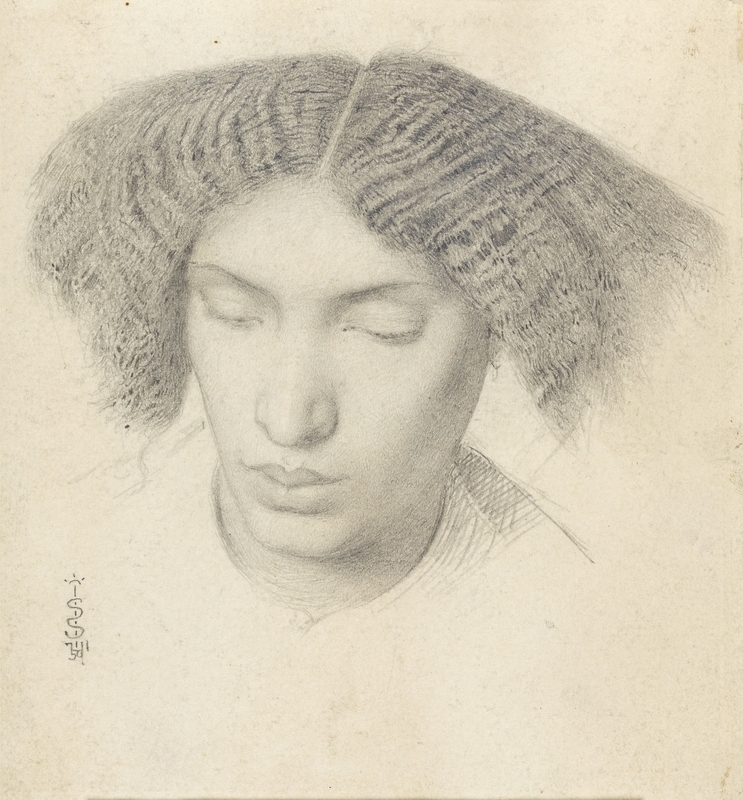

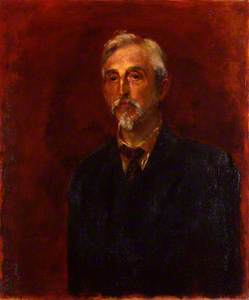

Recognised in his own lifetime as one of the greatest painters of the Victorian age, George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) created his 'Hall of Fame' portrait series as a gift to the nation. The series commenced in 1847, and numbered over 40 portraits by its close in 1901.

One of the sitters, the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837–1909), famously reported that Watts painted portraits 'only for three reasons – friendship, beauty, and celebrity', and this certainly seems to have been the blueprint for the series.

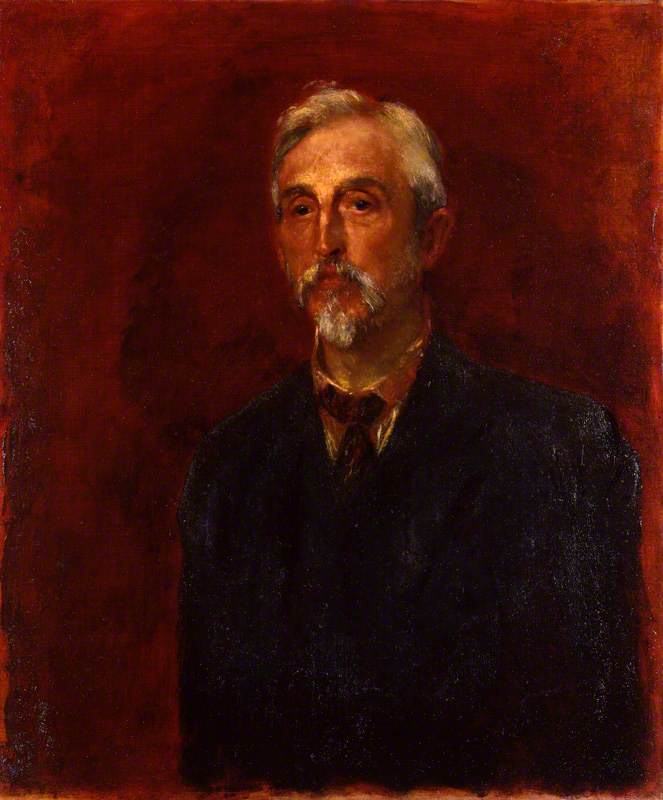

Eminent Victorian artists, writers, politicians, churchmen and philanthropists feature in Watts's pantheon of contemporary greats, revealing his far-reaching connections including social reformer Charles Booth (1840–1916) who organised the first scientific social survey of poverty in London, and the diplomat 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava (1826–1902), who held positions as Governor-General of Canada and Viceroy of India.

Frederick Temple Hamilton-Temple-Blackwood, 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava

1881

George Frederic Watts (1817–1904)

Watts intended his portraits to memorialise 'the men who make England' – but the artist acknowledged the subjectivity of his choice of sitters and of changing perceptions, noting that his subjects for the Hall of Fame 'may hereafter be found to have made or marred their country.'

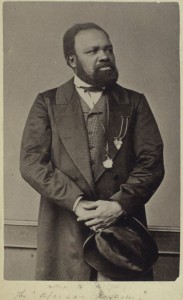

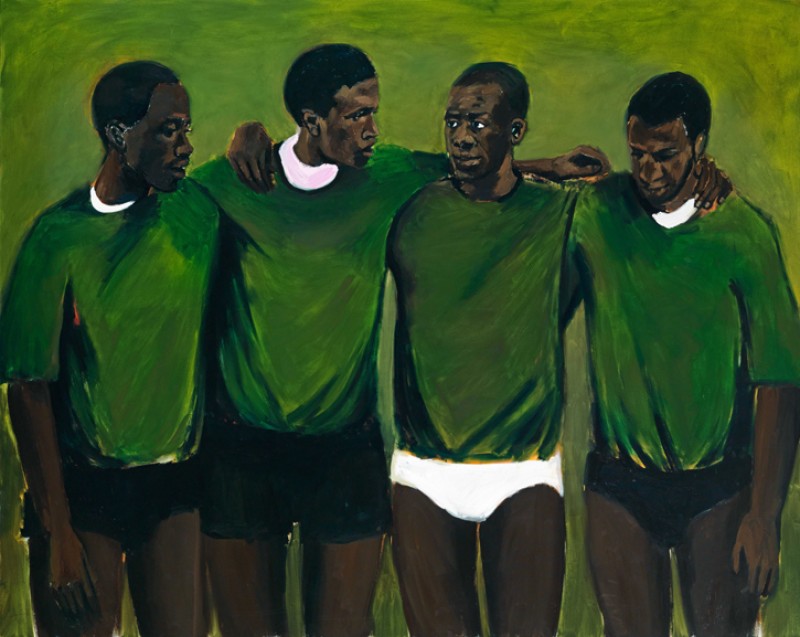

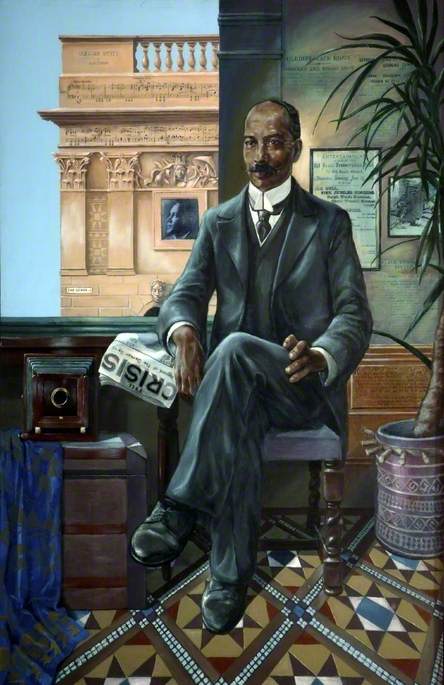

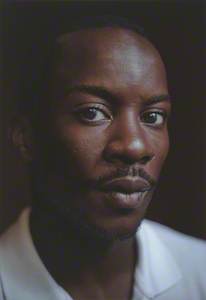

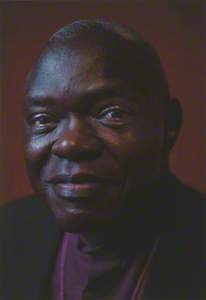

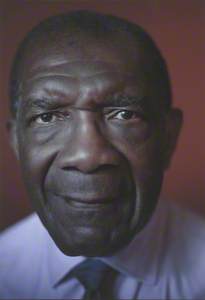

Over 100 years later, motivated by the same desire to create portraits of figures the artist deemed deserving of recognition, acclaimed photographer and filmmaker Simon Frederick (b.1965) brought together leading figures from the world of politics, business, culture, religion and science to celebrate Black British achievement today.

He photographed the sitters for BBC Two documentary Black is the New Black, originally shown in 2016, in which the subjects shared their experiences of being Black and British to paint a unique portrait of modern Britain's past, present and future. Frederick's sitters for Black is the New Black are trailblazers, breaking through historic and contemporary racial barriers.

Malorie Blackman (b.1962)

2016

Simon Frederick

They include the first Black writer to hold the position of Children's Laureate, Malorie Blackman (b.1962); Shevelle Dynott (b.1985), the first Black child to attend the Royal Ballet School; and model and campaigner against racism in the fashion industry, Naomi Campbell (b.1970).

Six painted portraits from Watts's series and twelve large-scale photographs from Frederick's have been brought together for the 'Faces of Fame' display. Hung alternately in juxtaposing lines, the portraits form a contemporary intervention at the heart of the Historic Galleries. The display explores key themes – from the artists' shared impulse to create their own personal hall of fame, to the representation of women (Watts's series of over 40 portraits notably included only one woman) and, importantly, empire.

In a twenty-first-century museum responsible for a nineteenth-century collection, this display encourages important conversations: about then and about now, about the changing face of fame and about wider societal change. 'Faces of Fame' highlights the enduring human urge to categorise and create hierarchies to make sense of the world, and yet as the changing reputations of Watts's sitters and the ever-changing celebrity landscape today reveal, fame is a shifting state.

Now open Faces of Fame: G F Watts X Simon Frederick: https://t.co/PWuFqrRStu #FacesofFame @artistSimonF

— Watts Gallery - Artists' Village (@WattsGallery) September 27, 2022

See the display in the Historic Galleries as part of your visit.

Created in partnership with @NPGLondon as part of their Inspiring People project. pic.twitter.com/AFXTJIuygh

Although working over a century apart, in different artistic media, sensibilities and similarities of approach emerge. Watts set out to 'reproduce not only [the] face, but [the] character and nature' of his sitters; this also rings true for Frederick.

Both groups of sitters are positioned against muted and predominantly dark backdrops, and most of them have pared-back un-fussy attire, so that the focus is on their illuminated faces and expressive eyes – the so-called windows to the soul. Every effort has been taken to draw out the personality of the sitter and capture that particular charged energy that emanates between artist and subject during a portrait sitting, and each has been captured with a pose and expression that is entirely theirs.

Some records exist of the portrait sitting process for the Hall of Fame, which brings Watts and his sitters to life. In one letter reflecting the artist's influence over his sitter's final appearance, Swinburne, though delighted to have been invited to sit for the great painter, complained that he was 'in the honourable agonies of portrait sitting – to Watts... he won't let me crop my hair.' The writer's tousled red mane, along with his bohemian necktie and far-away look conjure the romantic aura of an inspired, lyric poet.

Frederick prefers not to meet his subjects before their sitting, so that the authentic first encounter can be caught on camera. Most of the selected photographs were taken towards the end of the interviews, once the subjects had relaxed and assumed their most natural position and gaze.

Maggie Aderin-Pocock (b.1968)

2016

Simon Frederick

And how different they are, from the kind twinkle in the eyes of former Archbishop of York, John Sentamu (b.1949), to astrophysicist and science educator Maggie Aderin-Pocock's (b.1968) joyous look upwards – at the stars, perhaps? – and the piercing eyes and steadfast jaw of former trade union leader Bill Morris, Baron Morris of Handsworth (b.1938).

Both series reflect a broad range of professions, with perhaps a natural skew towards the arts. One interesting pairing that rewards closer inspection is of two visual artists: Walter Crane (1845–1915), a leading member of the Arts and Crafts movement and committed socialist, and Yinka Shonibare (b.1962), whose work explores the relationship between Africa and Europe, drawing references from Western history to examine race, class and cultural identity.

In Watts's portrait, Crane is dramatically lit as he gazes thoughtfully out of the picture. The artist has carefully rendered the sitter's wispy, thinning hair and waxed, twisted moustache. A white highlight on his necktie pin forms a glinting centre point to the otherwise dark-toned painting.

Frederick shows Shonibare facing the viewer, his head cocked with a quizzical or amused expression, but the photograph complements Watts's painting in other details – the sharp focus picking out the wiry grey hairs on the artist's chin, and the shine from his shirt button mirroring the watery glint in his eyes.

Looking at these works, hung side by side, we are confronted by the ways in which portraits can speak to each other across the centuries.

Ultimately, each artist's series reflects their circle of reference at the time of creation. By showing them together, Watts Gallery is encouraging its visitors to consider the wider concept of a national 'hall of fame'. Who deserves to be recognised and who gets to decide? We are inviting our audiences to join in the conversation, posing the question: who would you include in a 'Hall of Fame' today?

Emily Burns, curator at the Watts Gallery

'Faces of Fame: GF Watts X Simon Frederick' is open until 26th March 2023. The display has been created in partnership with the National Portrait Gallery as part of their transformational 'Inspiring People' project which includes an extensive programme of nationwide activities, funded by The National Heritage Lottery Fund and Art Fund.

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.