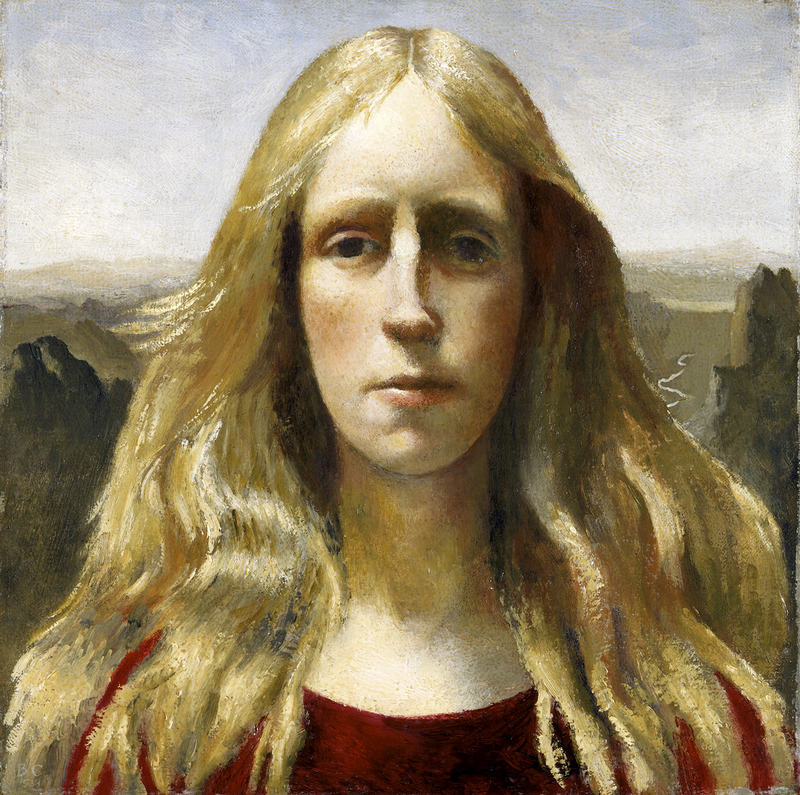

Shortly before her 32nd birthday, Frances Hodgkins left New Zealand in 1901 for Europe. She departed with a sound knowledge of historical European art gleaned from her father, William Hodgkins, who had taught Frances and her sister Isobel the pleasures of en plein air painting in the Otago landscape from a young age. In 1893 she had been introduced to the modern artistic revolution taking place in Paris from her Italian tutor, Girolamo Nerli, a Macchiaioli painter, and having passed the South Kensington examinations, she was qualified to teach.

Image credit: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, public domain (source: The Complete Frances Hodgkins, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki)

Cut Melons

c.1931, oil on canvas mounted on cardboard by Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947)

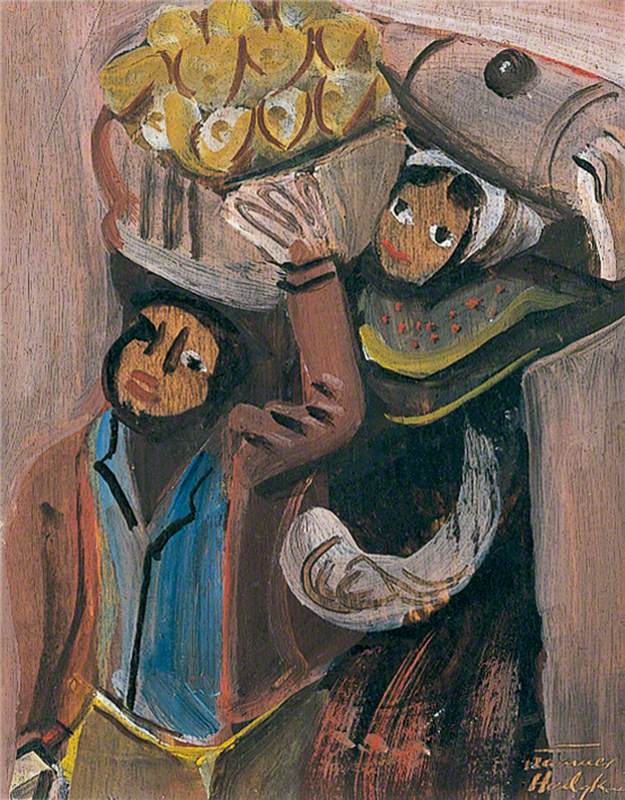

Unable to afford London, Hodgkins travelled to France, first to Brittany and then further south, working in an Impressionist manner, especially in her capture of light in the landscape, and her intimate portraits of mothers and working women, reminiscent of Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt. She spent three months in Morocco from 1902 to 1903, where the pared-back white cubic buildings, their walls reflecting light, allowed her further insight into what she later called 'the modern problem'.

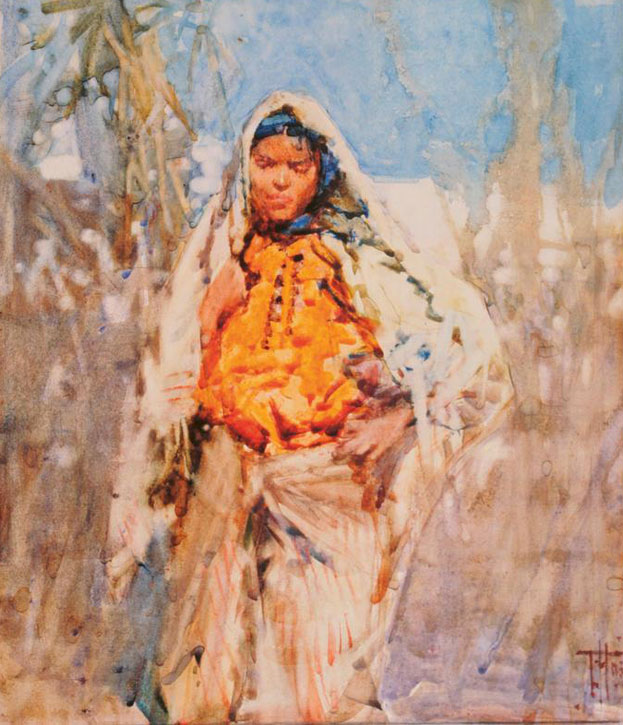

Image credit: private collection, public domain (source: The Complete Frances Hodgkins, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki)

Fatima

1903, watercolour on paper by Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947)

Figure studies in the landscape met with success in France and England, and she was able to write proudly to her mother when Fatima, one of her large Moroccan watercolours was hung at the Royal Academy in May 1903.

An engaging and lively teacher, in 1910 she was appointed the first female watercolour instructor at Académie Colarossi in Paris. The following year, she set up her own atelier at 21 Avenue du Maine in Paris and moved to Brittany for her summer school. She attracted a wide range of students from New Zealand, Britain and Canada.

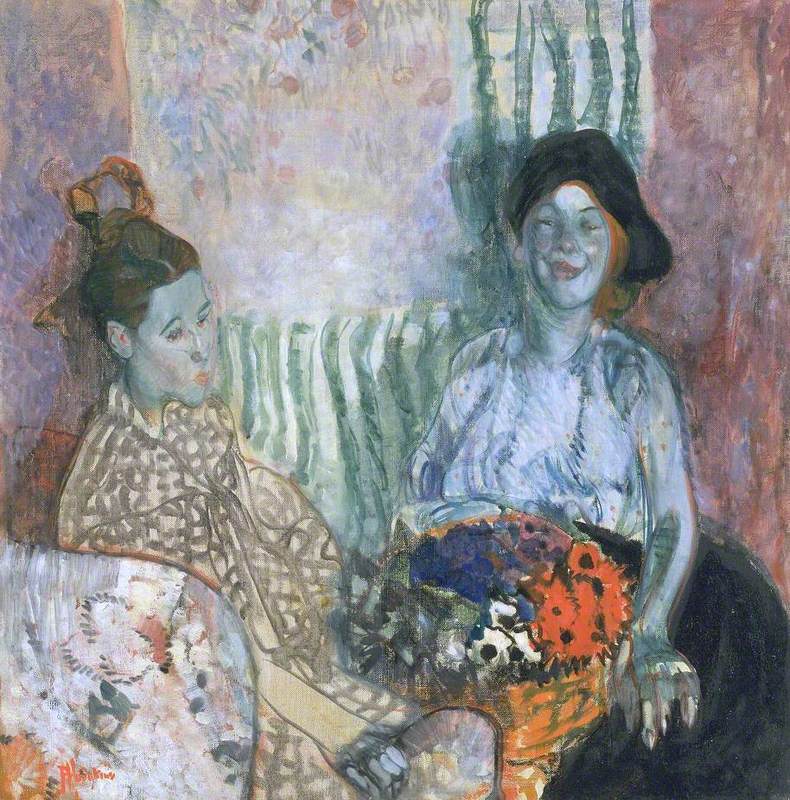

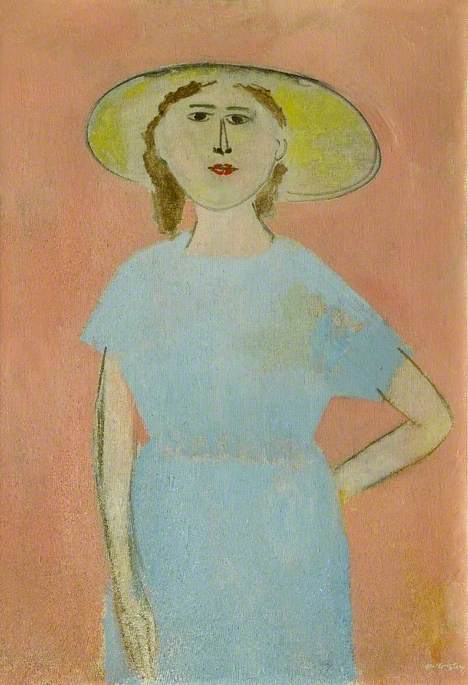

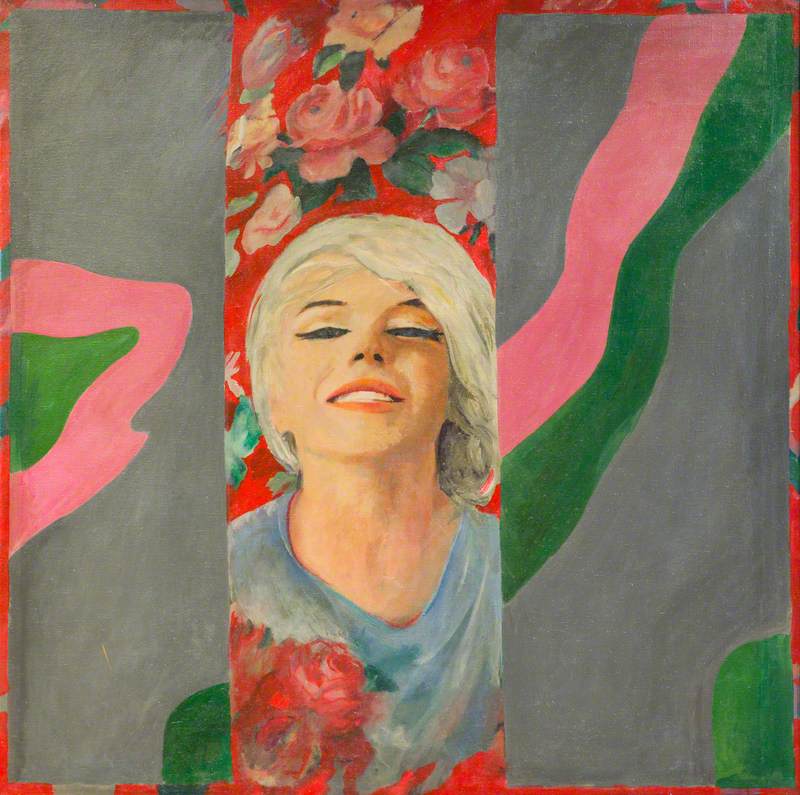

Forced to retreat at the outbreak of the First World War, Hodgkins chose St Ives over London, drawn by its remoteness from the theatre of war, as well as its thriving art community. Forbidden to paint outdoors, she turned to portraiture and produced large, experimental studies redolent of the bolder palettes of the Fauvists and Post Impressionists.

With its agglomeration of wavy stripes, dabs and checks, Loveday and Ann: Two Women with a Basket of Flowers, hints at the interiors of Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard, but this initial impression diffuses in light of the emerald green and orange complexions of the two sitters. Constrained by the sofa crammed into the corner of the room, their ill-fitting garments speak of the dressing up box. The girl on the left gazes forlornly into the distance, while her companion boldly returns the artist's concentrated gaze, as if sharing a joke that is lost on her friend. Beside the basket of flowers, her claw-like hand is feline – ready to pounce.

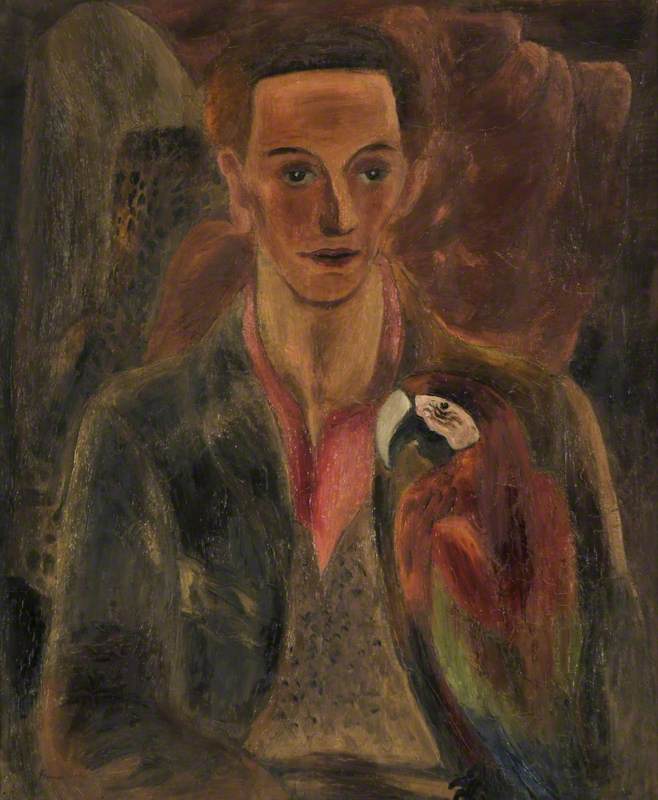

Against a background of drapery, the palette is much darker in this portrait of Hodgkins' friend and patron Mrs Hellyer. She leans towards us conspiratorially, her bobbed hair marking her a modern woman. The greenish-blue hues of her flowing jacket are reflected in the shadows of her eyes, with a further dab jauntily added to her nose.

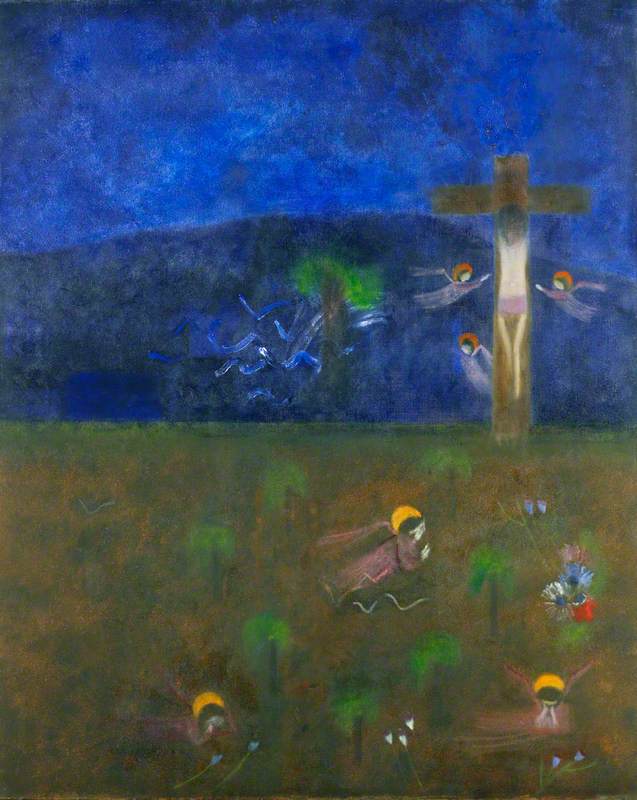

Shrine and Well – Le Treboul, Brittany 1922

Frances Hodgkins

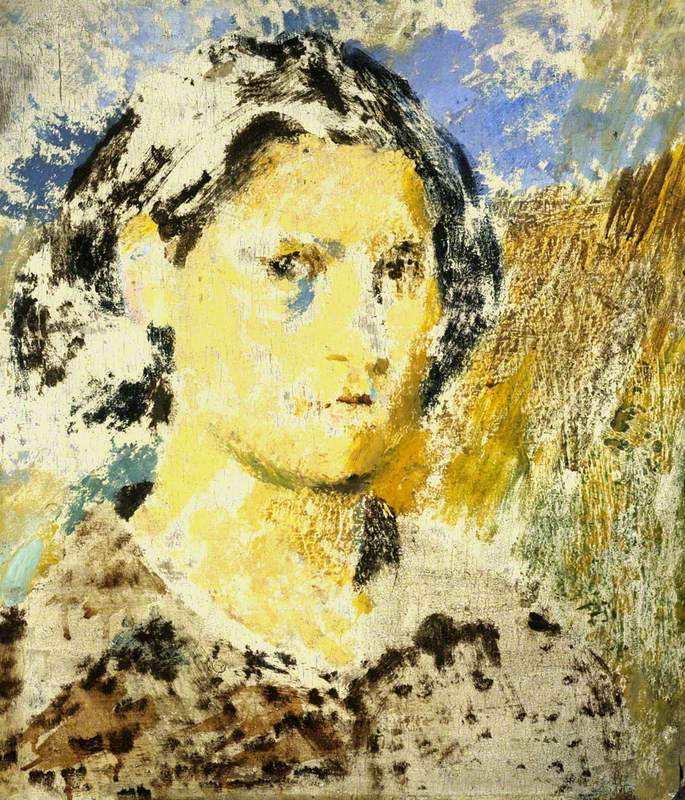

During the 1920s, Hodgkins spent most of her winters in different parts of the south of France. She also visited Tréboul in Brittany a number of times, where she painted several watercolours of the famous Shrine of St Peter, seen here in Well and Shrine. Her palette and application of paint have changed: she uses shorter parallel strokes to indicate forms, as if they are held in place by blanket stitch.

Image credit: Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hākena, University of Otago, public domain (source: The Complete Frances Hodgkins, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki)

Double Portrait

1922–1923, oil on canvas by Frances Hodgkins (1869–1947)

The 1920s was a decade of artistic experimentation against the backdrop of an economic recession in Britain, causing many artists, including Hodgkins, to endure periods of considerable hardship. In 1925 she had a year's respite when she was employed as a fabric designer at the Manchester Calico Association. Although well paid, Hodgkins returned to her peripatetic ways, telling her friend Elsie Barling that her employment was like being 'a race-horse shut in a stable', with no time left for her own work.

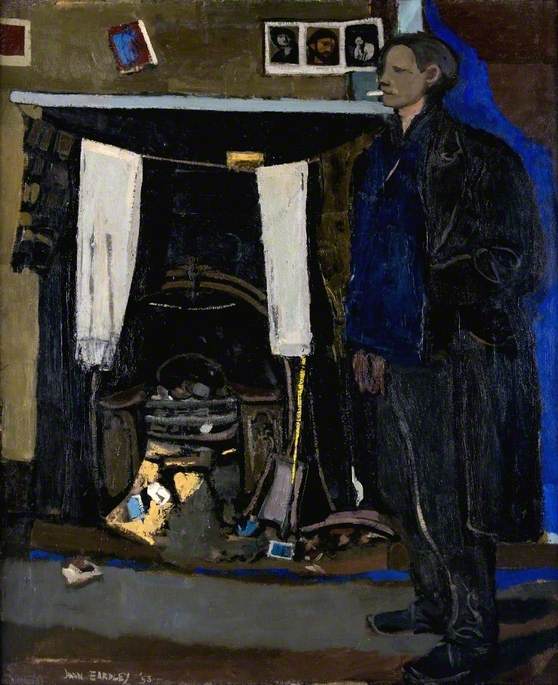

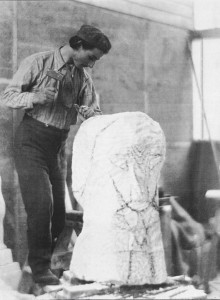

A breakthrough in public recognition came in 1929 when on the suggestion of her friend, the artist Cedric Morris, she was elected to the Seven & Five Society, exhibiting alongside Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson and Henry Moore. Graham Sutherland noted at the time, 'She was already speaking the language which gradually spelt freedom in art'. Hepworth recollected: 'I always remember, with considerable excitement, my first acquaintance with the painting of Frances Hodgkins...The work had great strength and purity and was so individual it was like discovering some new world'. In early 1930, aged 60, Hodgkins signed a contract with St George's Gallery.

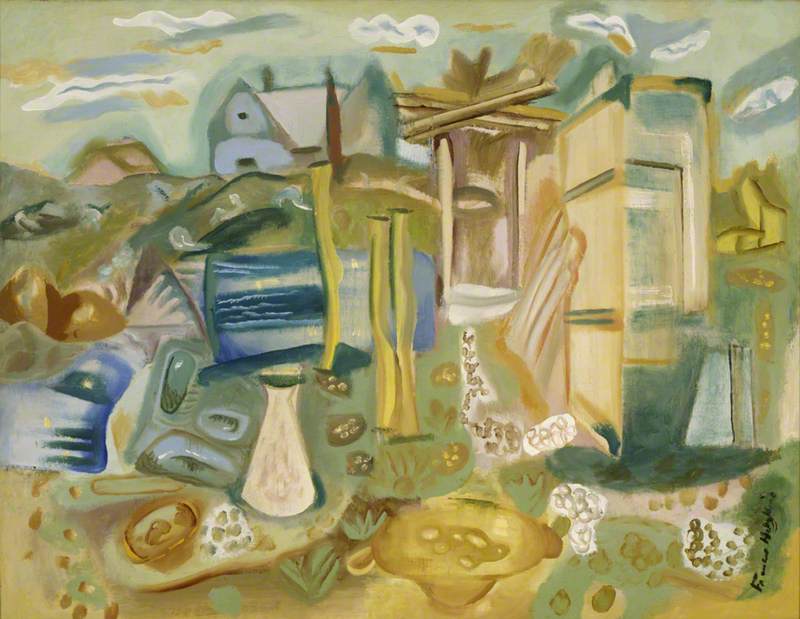

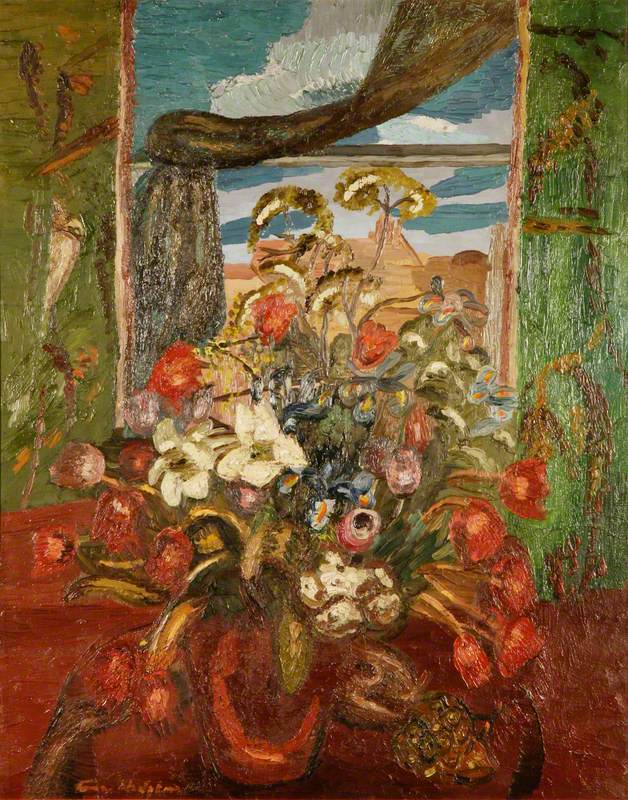

In 1929 she had begun experimenting with floating objects in the landscape. Flowers in a Vase looks like a conventional still life painting, the vase in question sitting on a table in front of a window. But the curtain hangs down from outside the window, adding a surreal quality to the composition. Shortly after painting this work, she gave up the traditional still life format, moving vases and objects onto outside tables. The curtain was retained in mid-air, then evolved into twisting cloth that animated the scene.

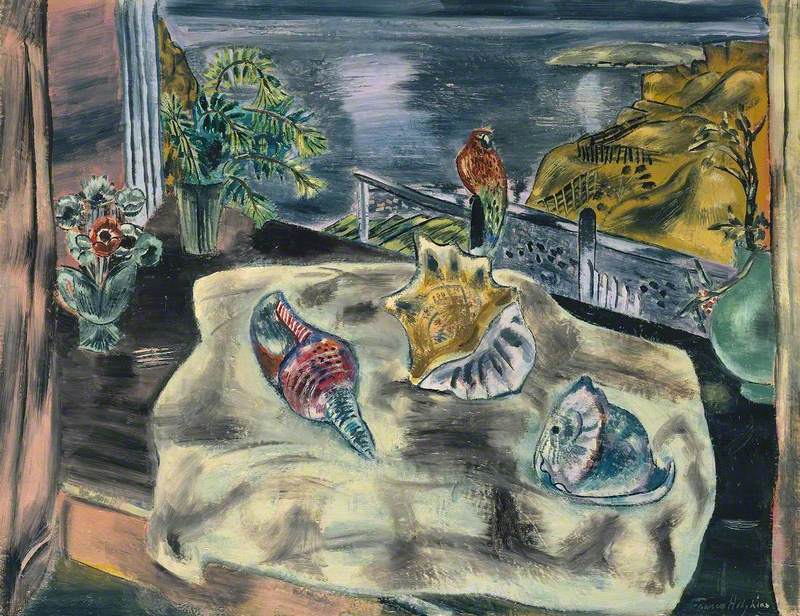

Both versions of Wings over Water derive from the winter spent in Bodinnick, Fowey in Cornwall. Painted from the same vantage point, in the Tate version shells are arranged on a rumpled cloth on the window ledge. Her landlady's parrot is perched on the fence overlooking the moonlit river. In this earlier version, Hodgkins has 'turned' the window so that it faces upstream, whereas in the painting belonging to Leeds Museums and Galleries, the focus is on Riverside, home of the young writer Daphne du Maurier, which is downstream on the left. Rob the parrot now hangs upside from a branch, and the window ledge floats in the foreground, released from its architectural frame.

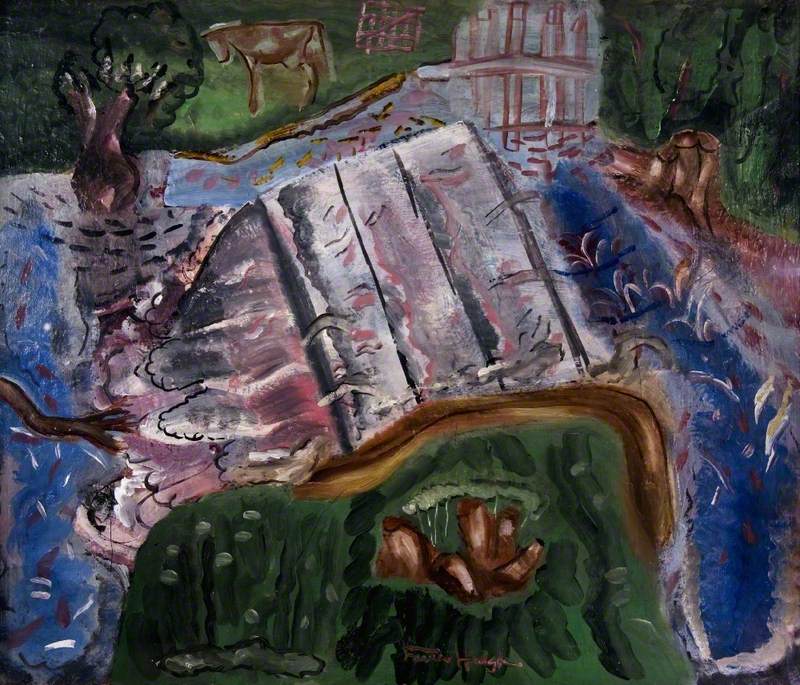

Although by the 1930s, she viewed England as her home, winters spent in Ibiza and Tossa de Mar on the Costa Brava brought new stimulus and innovation, and she would develop her ideas in the studio upon her return. From 1935 onwards, the villages of Worth Matravers and then Corfe in Dorset became her base.

While landscape remained her focus, farm objects and animals took the place of earlier still lifes, floating in and out of compositions like oddly suited abstract and surrealist dance partners, yet always somehow rooted in the here and now. Her palette was highly worked; her elusive and powdery tones were built up layer by layer over time.

Image credit: Felix H. Man (1893–1985), E. H. McCormick Archive of Frances Hodgkins Photographs, E. H. McCormick Research Library, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki

Frances Hodgkins at her Studio, Corfe Castle Village, Dorset

c.1945, photograph by Felix H. Man (1893–1985)

Hodgkins' friend and collector Geoffrey Gorer once put her success down to being a New Zealander and a woman, achieved at the cost of 'aesthetic loneliness'. Both stubborn and resolute, Hodgkins was fiercely determined not to imitate others but also knew that the price of success depended on a solitary working life. Yet to those who knew and loved her, it was her kindness, generosity of spirit, wit and curiosity that made her stand out among her peers.

One of the artists selected to represent Britain in the ill-fated 1940 Venice Biennale, and with a successful solo show at Lefevre Galleries, London the same year, Hodgkins' work was lauded in the press. The British writer and critic, Raymond Mortimer, for example, described her as 'unique', 'personal and original', 'visionary' and 'the most inventive colourist in England'. M. H. Middleton's review of Hodgkins' 1946 retrospective exhibition simply stated: 'she is one of the most remarkable woman painters of our own or any country, of our own or any time'.

Mary Kisler, Curator Emerita, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki