Artists often grow wilder with maturity. Emboldened by age and experience, they break free of the strictures of their schooling, leave behind naturalism, and find new ways and means.

The early drawings and paintings of Jack Butler Yeats (1871–1957) are robustly illustrative and very much of the world of Ireland and Irish types. We find local characters, boxers, jockeys and circus performers. Yeats was regarded as the Irish artist par excellence, his works described by Kenneth McConkey as 'delightful examples of pictorial Irishism'.

Untitled (Two Jockeys on Horses, Leaping a Stone Wall)

Jack Butler Yeats (1871–1957)

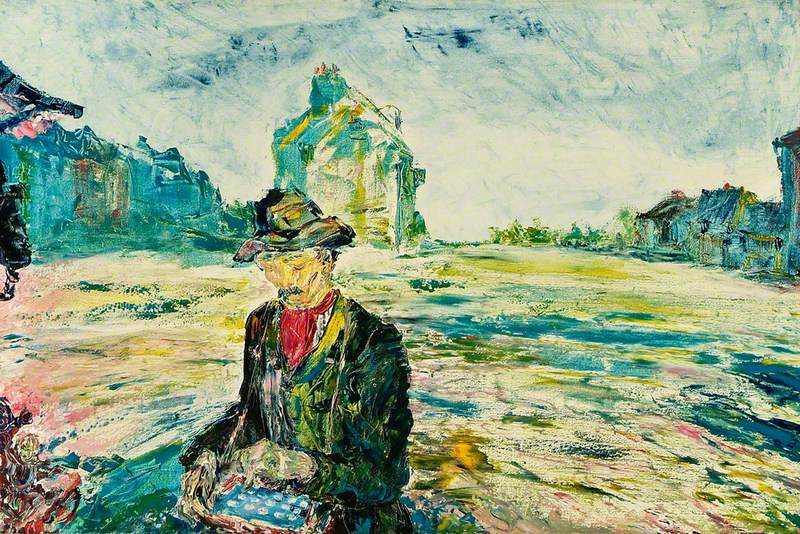

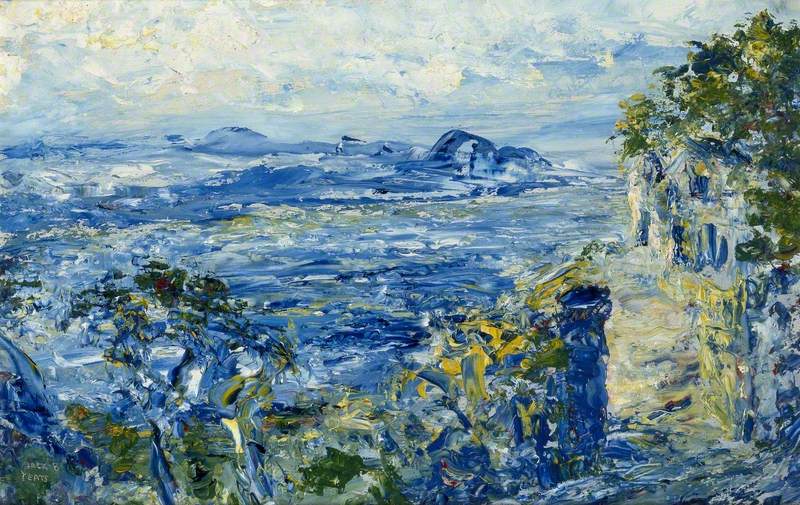

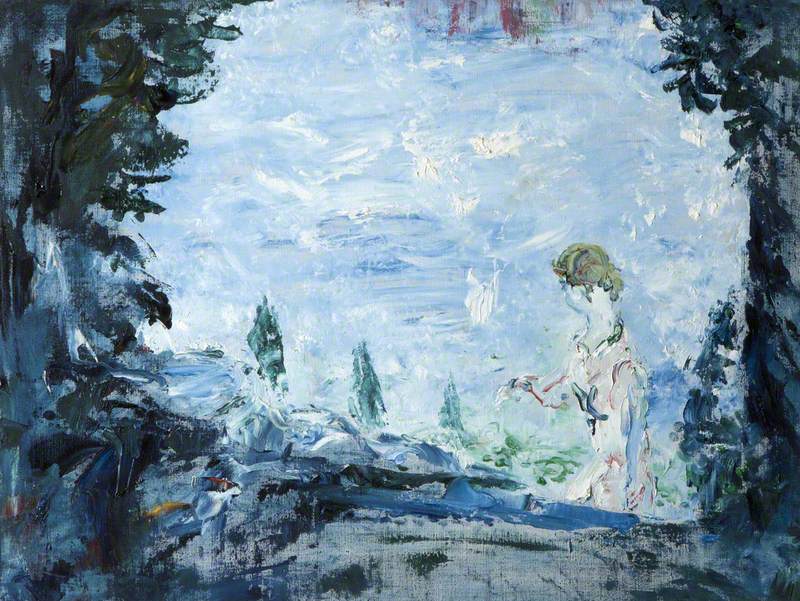

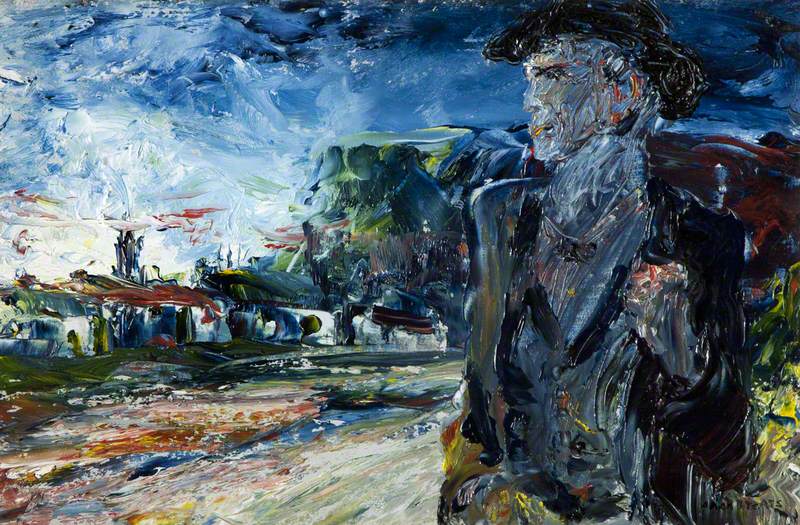

His later works, painted from when he was already in his mid-50s, might be by a different artist. They are exuberant, elusive, fluid and daring – dream-like, yet obstinately figurative. The Yeats scholar Hilary Pyle has described this development as similar to that undergone by his illustrious poet brother, W. B. Yeats, a move in which the artists' thoughts and feelings become more conspicuous in their art.

Many of Yeats's important works are in the Republic of Ireland, but there are several in the UK, in the Ulster Museum in Belfast, the Tate collection in London and other locations such as Leeds Art Gallery, the Ashmolean in Oxford and the National Museum of Wales.

An oft-quoted statement by Yeats sums up his view of art: 'No one creates… the artist assembles memories'. Yeats's mature style allowed him to use memory as the means by which his art was made. The 'spectral' quality of these late paintings (as Brendan Rooney aptly describes it) comes from the nature of memory as being vague and incomplete. Instead of precision, instead of detail, memory is a mood, a colour, with the topography barely sketched.

The figures in these paintings inhabit mindscapes rather than landscapes, and these mindscapes in some way inhabit them. It has been said that Yeats created a style not only based on memory, but which shows how memory presents itself, how it feels.

This shift to painting evoking memory and the past led the art historian Thomas MacGreevy to argue that Yeats was expressing an emergent Irish spirit, and he lauded Yeats as the great Irish national painter, drawing comparison with Rembrandt, Velázquez and Watteau. MacGreevy's friend, the writer Samuel Beckett, disagreed and read Yeats's development as wholly artistic, unrelated to external circumstance. For Beckett, Yeats is a genius whose qualities are rootless and more profound, 'because he brings light, as only the great dare to bring light, to the issueless predicament of existence…'

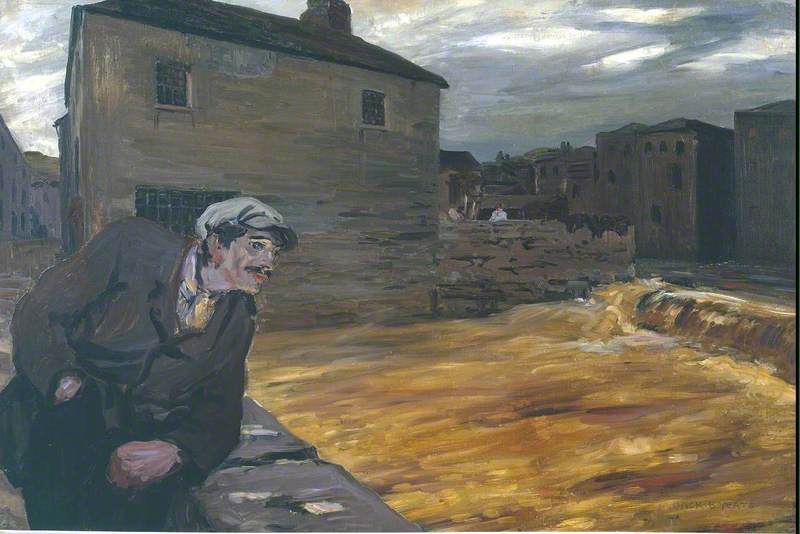

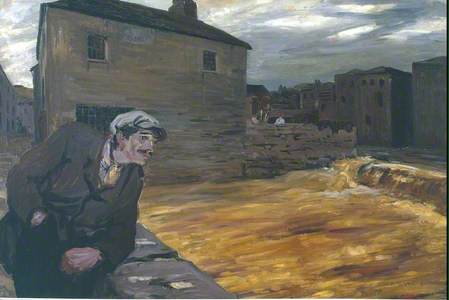

In 1923, around the time his style was changing, Yeats painted a man looking at a swollen river. The subject of contemplation runs through the art of Yeats. His main concern is people and their place in the world, their helplessness before it, their vain (in both meanings) attempts to put their stamp upon it.

Contemplative figures haunt his oeuvre. In the later paintings, they appear as ghostly accretions of the stuff of their surroundings, concentrations of matter, as if organically congruent with oceans and clouds. Yeats's figures can seem to be made of the same fabric as their surroundings. The very same brush, laden still with the blue of a river, creates the coat of the wanderer in On through the Silent Lands (1951), and the whole figure in The Explorer Rebuffed (1953) seems a distillation of sea and sky. As such, Yeats's figures are often barely discernible in the places they occupy.

What impressed Beckett was Yeats's depiction of the relationship between human beings and their environment: what he described as 'the unalterable alienness of the 2 phenomena'. Beckett contrasts Yeats's work with the landscapes of Constable, which he sees as 'infected with "spirit"', whereas the settings for Yeats's paintings are 'almost as inhumanly organic as a stage set'. Yeats often paints nature as a backdrop, as undifferentiated fields of colour, with land and water suggested rather than defined in a naturalistic way. In this way, he achieves a very Beckettian sense of human loneliness in an indifferent world.

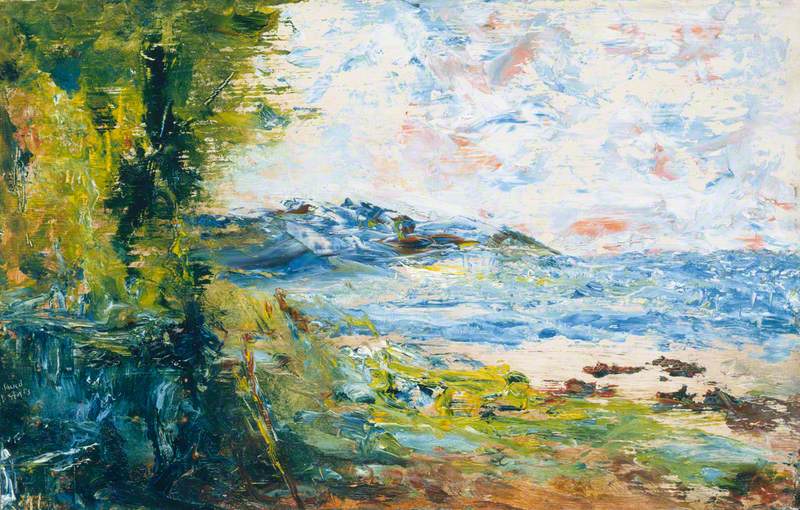

Queen Maeve Walked upon this Strand

1950

Jack Butler Yeats (1871–1957)

Yeats's use of oil paint – thickly and vigorously applied, described by Brian P. Kennedy as 'like icing on a cake, whipped up, dabbed on and dragged along the canvas' – produces images in which forms are shaped by the swirls and flicks of the paint itself, often suggested with just enough modelling to be there. In Men of Destiny (1946, National Gallery of Ireland), the men saunter all aflame, gilded by a sunrise, as if made of the light that breaks portentously at the horizon. The horse in Grafter's Glory (1954) is hardly defined as different from its setting, formed of those same daubs and colours.

In a rare case of an unpeopled, interior scene, The Scene Painter's Rose (1927, Trinity College Dublin), the picture is heavy with human presence: the painter has left his studio burning with the vivid colours of his work, and the flower, a frail miniature presence on the table, leaves us wondering as to its significance. A token from an admirer? Then we learn that Yeats himself often had a rose in a vase on his table, that he pinned an artificial one to his easel, and that a series of works featuring roses were to follow in the 1930s and 1940s.

The motif of the rose is a key to understanding Yeats. In an early painting, Bachelor's Walk, In Memory (1915, National Gallery of Ireland), a street vendor tosses a rose where the British army opened fire on Irish demonstrators in 1914.

Here's a closer look at Bachelor's Walk, In Memory by Jack B. Yeats, which has now joined the national collection.

— National Gallery of Ireland (@NGIreland) July 8, 2021

It's been on long-term loan to us for the past 12 years, and has now been purchased by the Gallery with the support of the Government of Ireland and private donors. pic.twitter.com/fXiWVUS5td

The rose – an age-old symbol of secrecy – had come to stand for Ireland in its struggle for independence, and it is said that Yeats adopted it in this vein. However, it soon became a personal symbol, and he produced a series of paintings in which the flower is seen at various stages of its decay. Ultimately, the rose became a source of Yeats's exasperation at the misunderstanding of his work.

In This Grand Conversation was under the Rose (1943, National Gallery of Ireland), Yeats 'uses the symbol to indicate scorn for spectators with too literal minds', according to Hilary Pyle. The painting was made following a dinner in Yeats's honour. Angered by 'empty words' and the presentation to his wife of a paper rose, Yeats resented the easy symbolic associations and vowed to paint only to his own satisfaction. The painting's title is a line from a revolutionary ballad, but Yeats supplants the original subject, depicting a clown (the artist) with his muse (a horse rider) under a rose attached to her whip. Thus the artist is shown as obedient to artistic inspiration, in a secret meeting, sub rosa.

In his 'Homage to Jack B. Yeats', Beckett wrote of the courageous artist – meaning Yeats, but also Beckett himself – as 'being from nowhere'. Beckett meant that the true artist has no country, serves no cause – but it may also suggest that Yeats's later art arrived quite unexpectedly.

Where did Yeats's mature work come from – this art that resists categorisation, belongs to no school, has no manifesto? It emerged from a tradition that was comfortably prosaic, often parochial and often twee, to take its place among the very best. An oddity: astonishing and worthy of the highest admiration.

As Beckett wrote: 'Merely bow in wonder'.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Samuel Beckett, 'Homage to Jack B. Yeats', in Disjecta, John Calder, 1983

Hilary Pyle, Jack B. Yeats: A Biography, Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1970

James White, Jack B. Yeats: Drawings and Paintings, Secker & Warburg, 1971