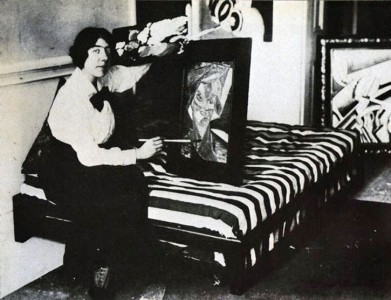

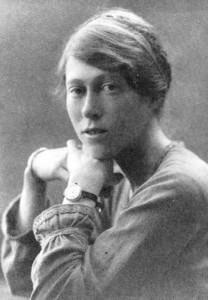

Collector, connoisseur, modernist writer and friend of artists, Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) was at the centre of Paris's cultural efflorescence of the early twentieth century.

Hosting weekly salons between 1905 and 1938 at her home, 27 Rue de Fleurus, Stein brought together leading names of twentieth-century art and literature. An exhibition at Nahmad Projects, London, 'Gertrude Stein: A Rose is a Rose is a Rose', reunites a group of artists whose work Stein collected and with whom she forged strong friendships.

It was at Stein's salon where Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse first met in 1906. Stein would later pair these artist-rivals in her twinned written portraits of 1909, describing Picasso's work as expressing 'a solid meaning, a struggling meaning, a clear meaning'. Meanwhile, Matisse's work is evoked more ambivalently: 'he certainly very clearly expressed something... some said that he did not clearly express anything'.

Hailing from a wealthy Jewish-American family, Stein and her brother Leo moved to Paris in 1903 and swiftly began collecting. While Leo would move to Settignano, near Florence at the start of the First World War, Stein remained in Paris for the rest of her life. However, she never relinquished her American identity. In 1937 Stein mused that 'America is my country and Paris is my hometown', reflecting the intimacy and camaraderie she felt with the Parisian avant-garde.

Leo, Gertrude and Michael Stein

1907, photograph by unknown artist

Moreover, Stein believed that her American identity was one reason she was able to connect so deeply with artists such as Picasso and Gris: writing in her seminal Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933) 'Americans... and Spaniards are natural friends'.

Stein's affinity, or in her own words 'intimacy', with Picasso and Gris manifested in her patronage, provision of financial aid and publications on both artists. For example, Stein was amongst the first collectors of Gris' work, purchasing his early Cubist paintings Glass and Bottle (1912–1913) and Book and Glasses (1914).

In addition, upon Gris' untimely death in 1927 Stein wrote a moving essay on his work for the Little Review noting that he 'combines perfection with transubstantiation'.

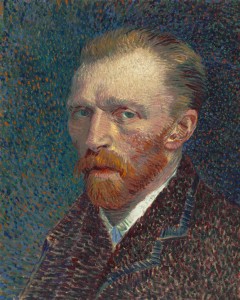

Picasso and Gris' friendships with Stein is also reflected in these artists' works. Most notable is Picasso's Portrait of Gertrude Stein (1905–1906).

In 1946, when Gertrude Stein bequeathed her portrait to The Met, it became the first painting by Pablo Picasso to enter the Museum collection.

— The Metropolitan Museum of Art (@metmuseum) August 6, 2020

Join Met conservators as they delve into the painting process of one of the Museum's most celebrated portraits.https://t.co/viQjmhy9L9

Here Picasso uses an Iberian mask to depict Stein's face, a stylistic device he would later adopt in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (1907). Set against a muted background and composed through shades of umber, greys and browns, Picasso portrays Stein isolated as the writer, thinker and listener.

Meanwhile, Gris' La liseuse (1926) is a painting developed from one of the four lithographs he created to illustrate Stein's novel A Book Concluding With a Wife Has a Cow (1926). La liseuse was used as the cover image of a centenary publication of Stein's Tender Buttons in 2013 and has been interpreted as a portrait of Stein.

La liseuse (The Reading Light)

oil on canvas by Juan Gris (1887–1927)

At first glance, the painting presents a standing female figure holding a book – the eponymous reader. However, on closer inspection, the complex structure of the painting unfolds. The composition is anchored around an abstracted form of a book with layer upon layer of rectilinear forms echoing the pages of a novel building on one another.

This is most notable in the lower right of the composition. Here the lined pages of the book join another set of lined pages set against the background of a row of houses. Gris creates a mise-en-abyme – a copy of an image within itself. The abstracted and multi-layered structure of this work reflects the complex form and meaning of Stein's writing.

While Stein began collecting with her brother Leo, purchasing works including Matisse's infamous Femme au chapeau (1905), by 1913 they had parted ways. This was due to disputes on modern painting and Stein's increasingly radical practice as a writer.

We can only assume that #NationalHatDay is one of her favorite holidays. [Henri Matisse, Femme au chapeau (Woman with a Hat), 1905] pic.twitter.com/5Y6sU27IBJ

— SFMOMA (@SFMOMA) January 15, 2017

Leo kept all 16 works they had amassed by Renoir who he believed to be the greatest living painter. Meanwhile, Stein retained works by Matisse and Picasso and subsequently began collecting a wide roster of artists including Kees van Dongen and Marie Laurencin.

La rue de la Paix

1918, oil on canvas by Kees van Dongen (1877–1968)

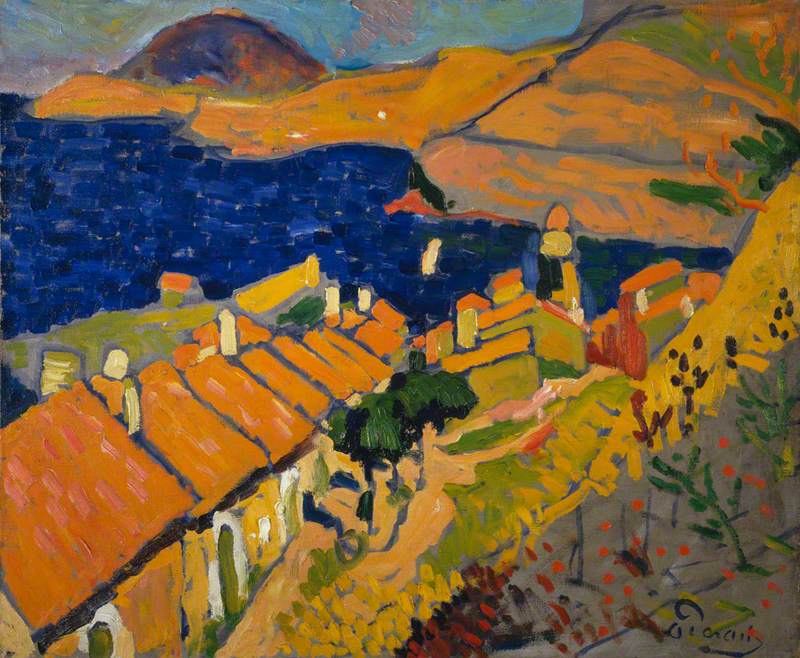

The divergence of Stein and Leo's tastes is reflected through a comparison of Renoir's The Umbrellas (1881–1886) and Van Dongen's La rue de la Paix (1918). Sharing a similar subject matter of a bustling high society Parisian street, Van Dongen's work represents a radical departure from the naturalism and sentimentality of Renoir's earlier painting.

Indeed, Stein stated in 1945 that her ambition for literature and art was to 'kill the nineteenth century'. Using sparse brush strokes and sinuous lines Van Dongen depicts the twentieth-century modern woman through a sensuously minimised language of form. The women appear to float in space, together yet apart, reflecting the subtractive and decentralised style that Stein championed and adopted in her writing.

Further analogies can be drawn between Stein's writing and the Cubist paintings she collected. Indeed, the literary critic Michael J. Hoffman reflected that Stein was amongst a group of modernist writers, including T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound, and painters including Picasso, Gris and Georges Braque, who sought to 'fragment the structures' of reality in order to 'reconstruct the world anew'.

Stein's writing and Cubist painting powerfully attest to a new sense of order. There is a break with conventions of narrative, composition and perceptions of space and time as linear. This reflects a wider zeitgeist following Albert Einstein's new articulation of space in time in his General Theory of Relativity (1915). She once declared: 'Einstein was the creative philosophic mind of the century, and I have been the creative literary mind of the century.'

Guitare sur une table

1921, by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

In texts such as Stein's Tender Buttons (1913) and paintings such as Picasso's Guitare sur une table (1921) there is a focus on objects, dislodged and disjointed from conventions of form. In both works, phrases of text and sections of the image are fragmented, shifting in and out of focus. Indeed Stein's description of Picasso's work in Tender Buttons reflects the sensation of looking at his still life. She writes 'a table means a revision of a little thing... a stand where it did shake.'

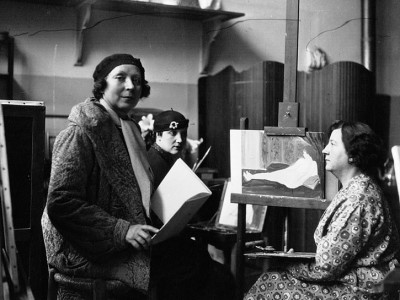

Dinner party at the home of Bobsy Goodspeed, Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas with friends

Stein's life and work have had a powerful legacy on twentieth- and twenty-first-century culture. Following her death in 1946, her writings became a source of fascination to the interdisciplinary commune of artists living and working at Black Mountain College, North Carolina, a community characterised by its collective exchange of ideas.

In the epigraph of Ernest Hemingway's The Sun Also Rises (1926), a reference to the 'lost generation' pays homage to Stein, who coined the term to describe the 'disoriented, wandering, directionless' creatives in the years following the First World War. In spite of this, generations of artists 'found' their place within Stein's salons.

Cora Chalaby, art historian and writer

'Gertrude Stein: A Rose is a Rose is a Rose' is open from 3rd June to 29th July 2021 at Nahmad Projects