On Father’s Day, us art historians should remember the painter, architect and biographer Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574).

Why? Because his book Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, first published in 1550 in Florence and in a greatly enlarged edition in 1568, was 'perhaps the most important book on history of art ever written' (Peter and Linda Murray, 1963), making Vasari the first art historian in the modern sense.

Everyone who has studied the history of art will have heard of Vasari. Although he may not be a household name, if you have been to Florence and visited the Uffizi gallery, which was designed by him, you will have seen in its endless corridors the work of the artists whose lives he told with lively anecdotes, and whose paintings he described and assessed.

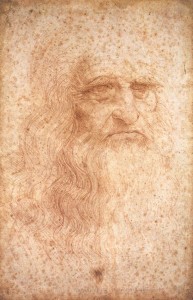

It is due to Vasari that we owe the conventional art historical view of the Italian Renaissance (and thus western art) as having originated, been developed and brought to perfection in Tuscany – in particular Florence – and in Rome. According to Vasari, the achievements of Greek and Roman architects, sculptors, painters and poets were lost in the Middle Ages and only began to be revived in Tuscany in the fourteenth century. The arts were reset on their true path by Cimabue and Giotto, progressed by artists such as Brunelleschi, Donatello and Masaccio, and bought to perfection in his own time by Raphael, Leonardo and Vasari’s idol Michelangelo. 450 years later, this trio are still recognised as the greatest masters of western art and many of his other judgements have also stood the test of time.

The Head of a Bishop

(possibly Saint Ambrose or Saint Donato) 1569

Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574)

Born in Arezzo, Tuscany, Vasari was a bright boy, classically trained and encouraged in drawing by his distant cousin Luca Signorelli. He went to Florence in 1524 to study under the patronage of the ruling Medicis with Andrea del Sarto. In 1529 he visited Rome and studied the work of Raphael and artists of the Roman High Renaissance. He was patronised by the Medicis in Florence and worked there and in Rome, most successfully as a decorative painter in palaces and cathedrals, including the Vatican. He was also a talented architect and in 1563 helped found the Florence Academy. But the reputation of Vasari’s own paintings, heavily influenced by Michelangelo, declined in the following centuries.

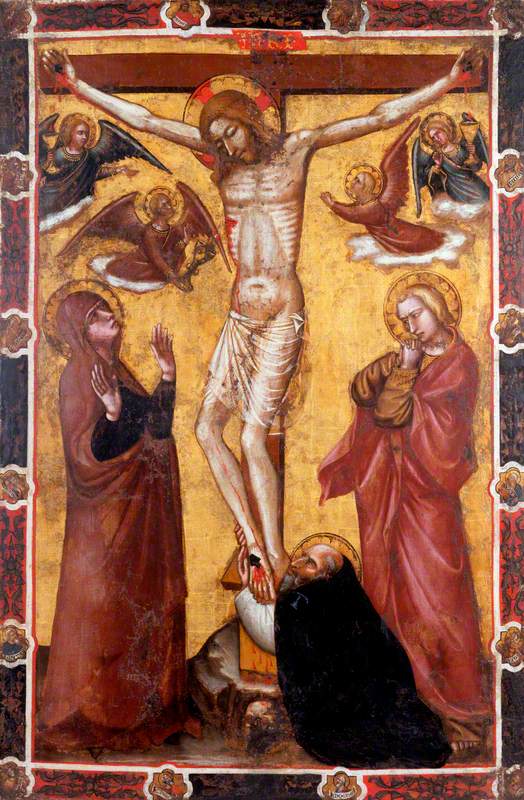

An Allegory of the Immaculate Conception

c. 1540

Giorgio Vasari (1511–1574)

Vasari was encouraged to compile his Lives of the Artists when he was in Rome in 1546. With the help of numerous contributors and his own enormous visual memory, his monumental book follows the belief of his times – that the purpose of art is the imitation and perfection of nature and that progress in art can be measured by how far it achieves this aim. In the first edition the credit for this progress is biased heavily in favour of the Florentines: the book is dedicated to Cosimo de’ Medici, who wanted Florence to be seen as the centre of world culture and civilisation.

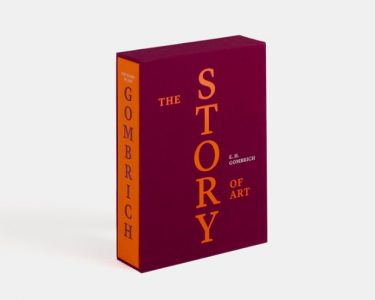

He is careless with dates, some of his anecdotes are hearsay or traditional myths, but, particularly with the artists of his own day, he is still a fundamental source of information on Renaissance art. His biographical model of art history, with its interest in personality and character as well as achievement, was influential across Europe in the seventeenth century. His approach informed art historical writing well into the twentieth century – Gombrich’s bestseller The Story of Art begins: 'There really is no such thing as Art. There are only artists.'

Andrew Greg, National Inventory Research Project, University of Glasgow