Primarily known as a portrait painter, Glyn Warren Philpot (1884–1937) received great recognition during his lifetime. In 1913 he won first prize at the Carnegie International competition in Pittsburgh, he was elected a Royal Academician in 1923, and in 1930 he had a one-man exhibition at the Venice Biennale. However, Philpot's reputation declined temporarily when his early and more traditional style changed. Responding to the new tendencies in modern European painting, and exploring a visual language that expressed his personal concerns, including his religious belief and homosexuality, Philpot's aesthetics became ever more singular and distinctive.

Shortly after his death, Philpot was accorded a retrospective at the Tate Gallery in 1938, but his fame waned after the Second World War and his work became increasingly marginalised within British art history until a retrospective National Portrait Gallery in 1984. This is due perhaps to the difficulty of classifying an artist whose painterly styles are so various and whose subjects are suggestive and ambivalent, lacking affiliation with other English modernists. Outside his portraiture, the underlying interest in the male body displayed in his work was rarely analysed and it is only since the 2000s that the theme of homosexuality is being properly acknowledged. In 2017, Brighton Museum and Art Gallery opened a retrospective display of Philpot's work in the context of the many LGBTQ exhibitions and events across the museum, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in the UK.

Brighton Museum and Art Gallery held the first large exhibition of Philpot's work in 1953 after his memorial exhibition at the Tate Gallery in 1938. The museum was one of the few institutions to recognise Philpot's accomplishments at the time and many of the artworks in the collection were given by Philpot's family, primarily his sister Daisy Philpot, brother Leonard Philpot and niece Gabrielle Cross. In a letter of 1973 to the museum, Gabrielle writes how she wants the collection to reflect the full span of Philpot's work and his courageous search for new expressions. The collection includes examples of Philpot's early portraiture, his religious and spiritual paintings from the 1920s, subject paintings including his depiction of black male figures, his later, more modern, portraiture from the 1930s, and plaster and bronze sculptures.

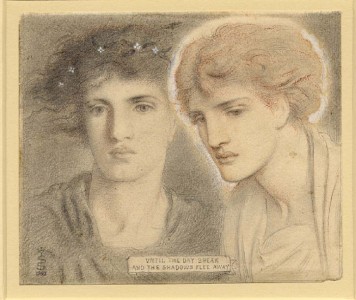

In 1904 one of Philpot's paintings was included in the Royal Academy's annual Summer Exhibition and this led to his first portrait commission. By 1911 he was living and working in a studio flat in London and successfully established as a society portrait painter. Up to 12 portrait commissions a year enabled him to travel in Europe and later to America, absorbing the modernising influences of portraits by Velázquez, Goya, Manet and others. Parallel to his portraiture, Philpot produced less formal narrative scenes with looser brushwork, some influenced by French Symbolism. This more personal work was shown at his first one-man exhibition in London in 1910, but received far less critical acclaim than his portraits.

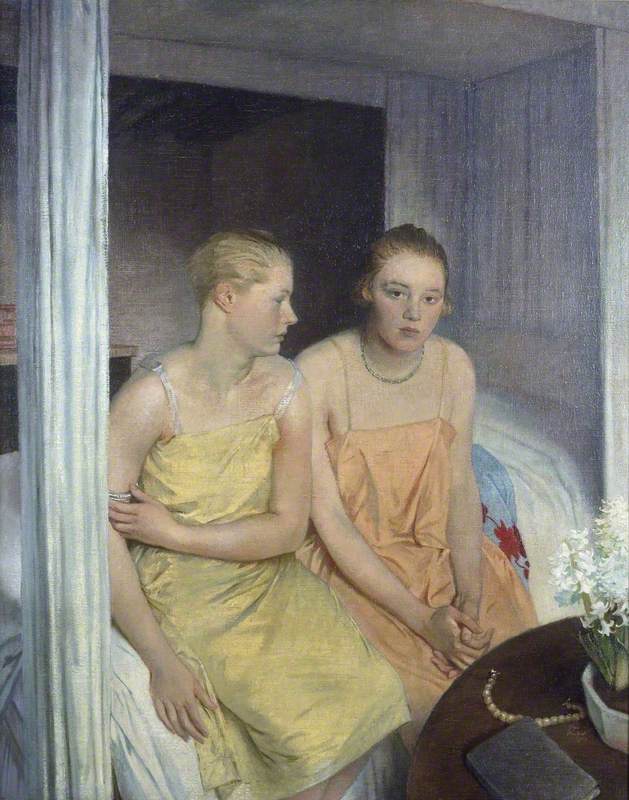

Mrs Basil Fothergill and Her Daughters, Rosemary and Barbara

1910

Glyn Warren Philpot (1884–1937)

Mrs Basil Fothergill and Her Two Daughters (c.1911), one of the first of his works donated to Brighton Museum & Art Gallery, demonstrates his skill in effectively combining traditional portraiture with more modern styles. The soft folds and contours of Mrs Fothergill's black dress are skilfully rendered against a lighter black background, contrasting with the brightness of her daughters' yellow dresses and the bold, loose paintwork of the grey scarf across the elder daughter's knees. In 1906 and 1910 Philpot had travelled to Spain, and the influence of Spanish painting in this portrait would have contrasted with many of the more traditional, academic portraits by his British contemporaries.

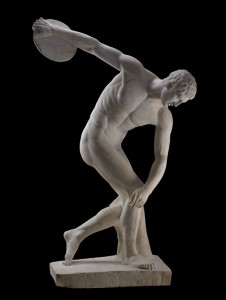

Following his conversion to Catholicism in 1905, Philpot explored religious and spiritual subject matter throughout his career. Such themes were unpopular among his contemporaries, but enabled Philpot to combine his religious conviction with an appreciation for the beauty of the male figure. His production of religious paintings increased significantly after he visited Florence and central Italy for the first time in the early 1920s.

The Angel of the Annunciation

1925

Glyn Warren Philpot (1884–1937)

In the painting The Angel of the Annunciation (1925) the archangel Gabriel is portrayed as a muscular and sensuous young man kneeling in front of a red brick porch. Instead of wings, he has a billowing red cape, and looks compassionately towards the Virgin Mary, whose presence is merely suggested by the abandoned knitting pins and yarn. The viewer of the painting takes on the perspective of Mary, becoming the recipient of Gabriel's Annunciation. Instead of the traditional lily that signified Mary's devotion and purity, Gabriel offers an anemone. In Christian iconography, the anemone, a wildflower, symbolises the purity and brevity of Christ's life, and in classical mythology, it symbolises Aphrodite's tears when she mourned the death of her youthful lover Adonis. According to Philpot's brother Leonard, the setting was inspired by Leonard's cottage in Bedham, near Fittleworth, Sussex, where Philpot stayed before working on The Angel of the Annunciation. Philpot's very modern interpretation of the Annunciation received mixed reviews in the press.

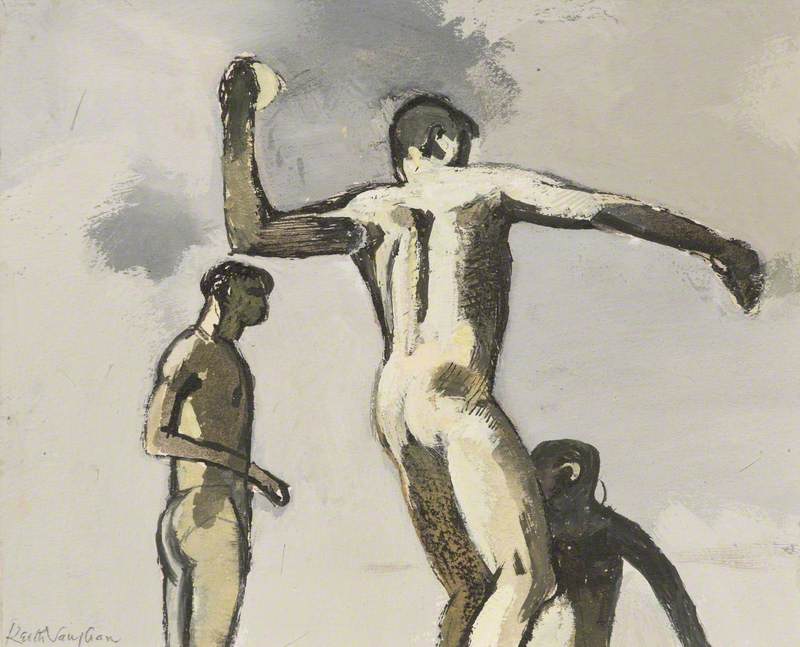

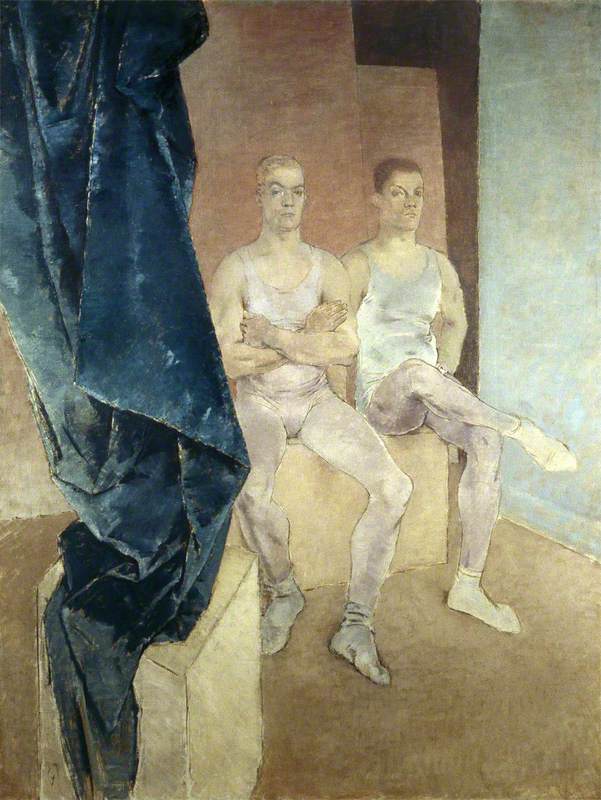

Acrobats Waiting to Rehearse

1935

Glyn Warren Philpot (1884–1937)

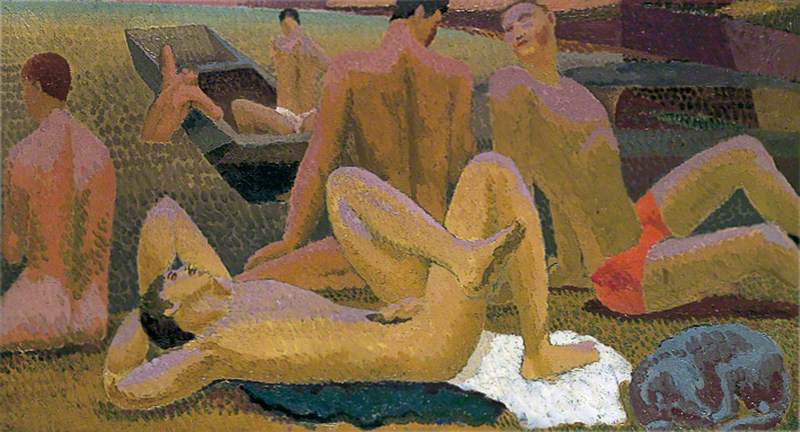

The impact of European modern art on Philpot's work and the change in style that characterised his paintings of the early 1930s is also visible in Acrobats Waiting to Rehearse (1935). Behind heavy drapery, two seated and muscular male acrobats stare solemnly ahead. We are invited to peep into an intimate, private space far removed from the spectacle of public performance. The almost monochrome light pink hues and the contemplative mood reveal the inspiration of Picasso's Rose Period. Philpot may have been influenced through his role on the Jury of the Carnegie International competition in Pittsburgh (1930) where he served alongside Matisse, and where the first prize was awarded to Picasso. In 1931, Philpot lived in Paris and the artistic ferment of Parisian modernism further influenced the development of his work.

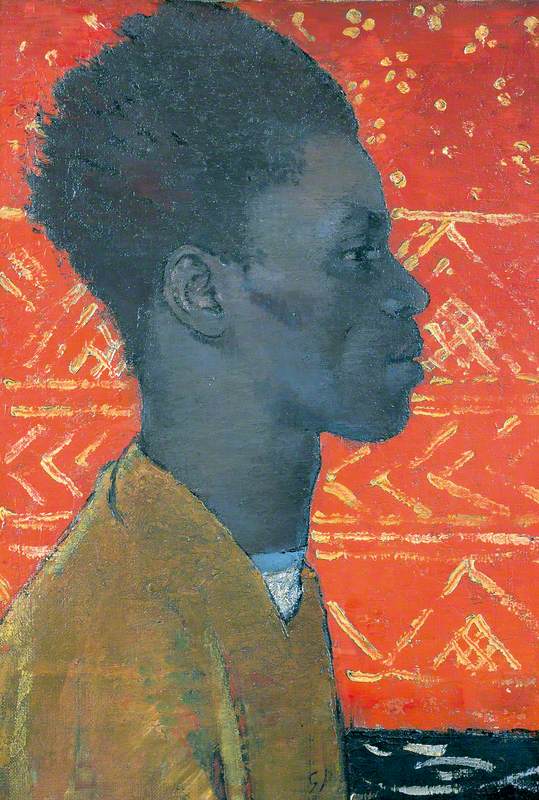

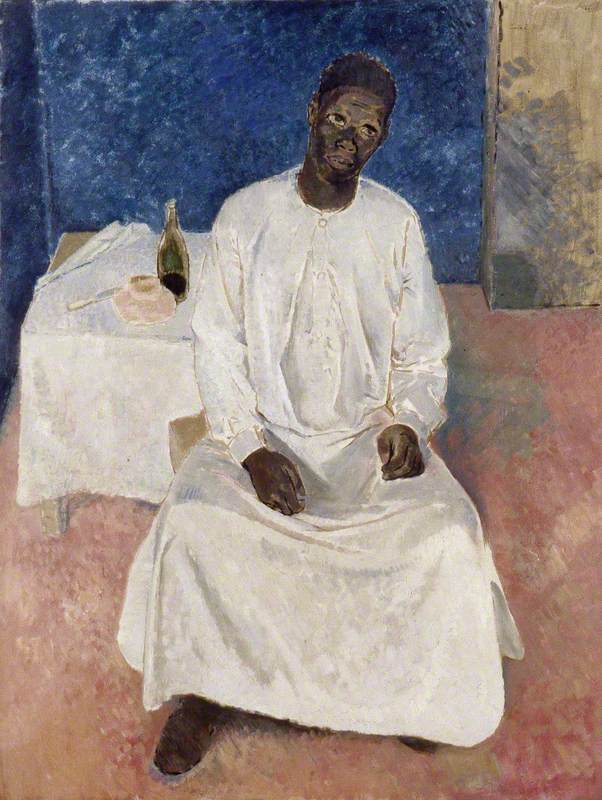

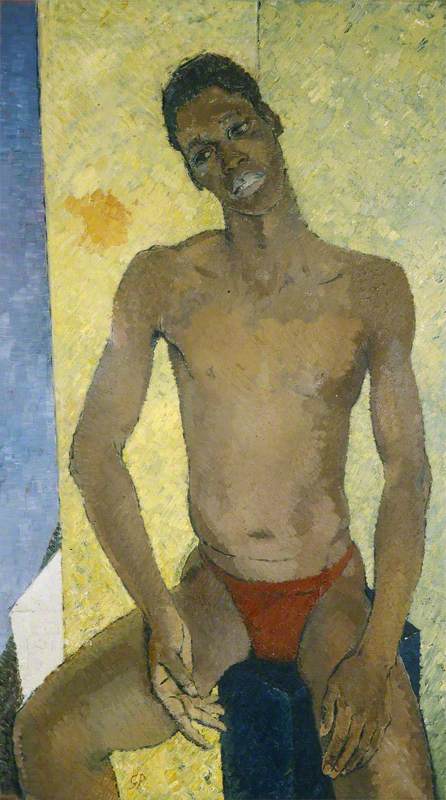

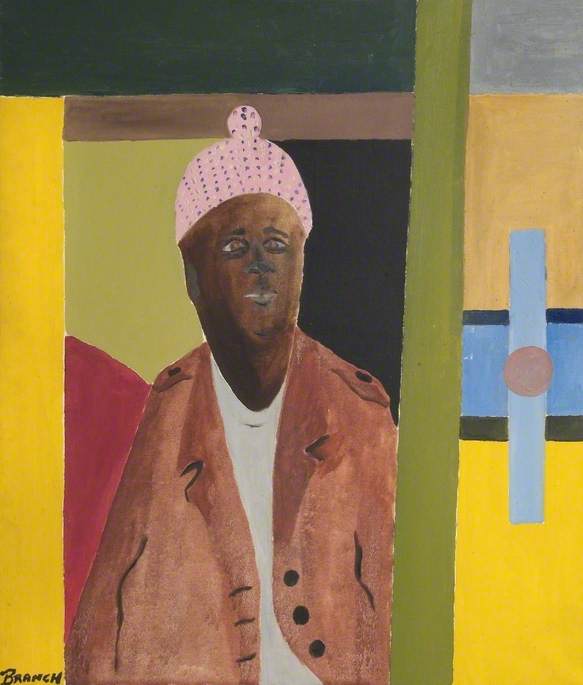

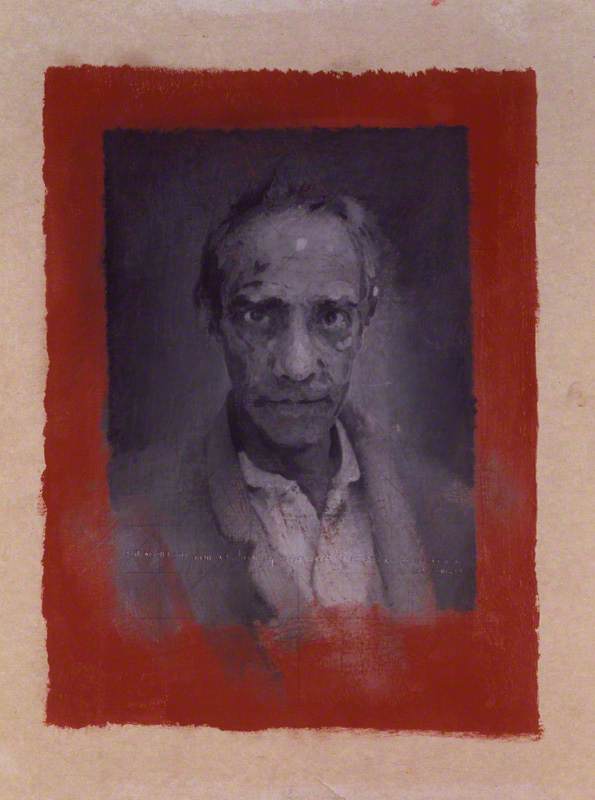

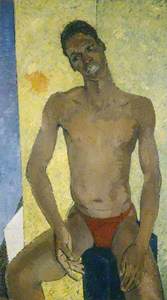

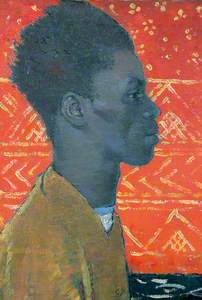

Philpot was introduced to Henry Thomas in 1929, after the Jamaican had missed his boat home. He became Philpot's servant and companion, remaining with him until the artist died in 1937, and was the model for all Philpot's paintings of black men from 1932. On visits to America and Paris, Philpot frequented jazz clubs and had made sketches and painted portraits of black men. At a time when few portraits of black men were painted by white artists, Philpot's paintings and drawings display empathy and sensitivity towards his sitters.

In Melancholy Man (1936), Henry Thomas's long torso and limbs are accentuated and the tilt of the head and the open arms and hands suggest a passive gentleness, the gold background accentuating the sensual rendering of the model's skin. The blue strip at the left gives depth to the painting and makes solid the figure in space. This feminised, languorous portrayal of a black male hints at Philpot seeing black men as 'other', onto which he could project a coded homoeroticism otherwise difficult in the censorial society of the 1930s.

Living at a time when homosexuality was a criminal offence, Philpot was never explicit about his sexuality. He had a long relationship with Vivian Forbes whom he had met in the Royal Fusiliers around 1914 and from 1923 to 1935 they intermittently shared a home and studio at Lansdowne House in London. Forbes had been a businessman in Egypt but, encouraged by Philpot, he became an artist, exhibiting at the Royal Academy and elsewhere throughout the 1920s. During the 1930s Philpot suffered from high blood pressure and breathing difficulties and he spent the summer of 1937 on convalescence in France with Forbes. On 18th December that year, Philpot collapsed suddenly in London and died of a brain haemorrhage. Forbes took his own life the following day.

Nicola Coleby, Partnerships & Development Manager, and Jenny Lund, Curator of Fine Art at Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove