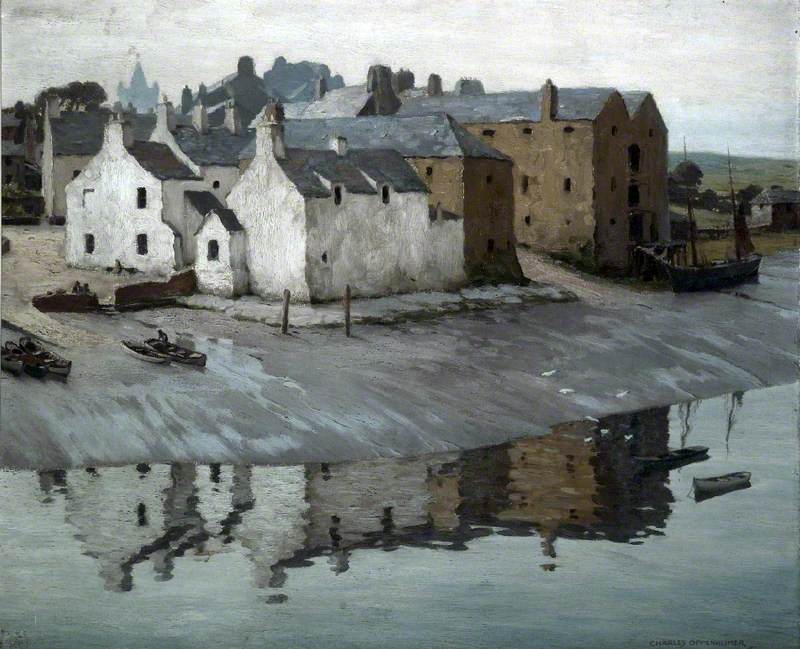

On the north coast of Rousay, a small island in Orkney, a rough-hewn slab of Portland stone sits in the converging squall of the Atlantic Ocean and North Sea. About 7.5 metres long and 2 metres wide, Ian Hamilton Finlay's Gods of the Earth/Gods of the Sea was commissioned by The Pier Arts Centre and installed in 2005, its surface design executed by the stonecarver Nicholas Sloan.

Gods of the Earth/Gods of the Sea – Ian Hamilton Finlay, Sited on Rousay in 2005

2007

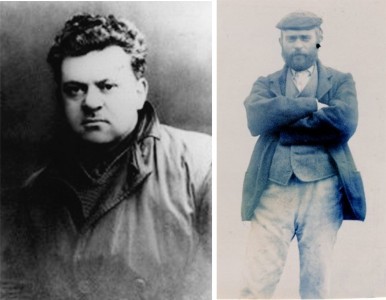

Robin Gillanders (b.1952) and Nicholas Sloan (b.1951) and Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925–2006)

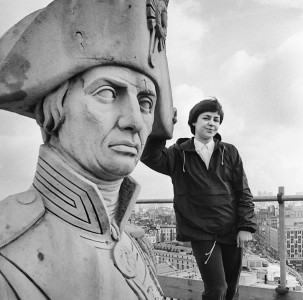

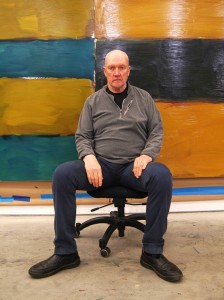

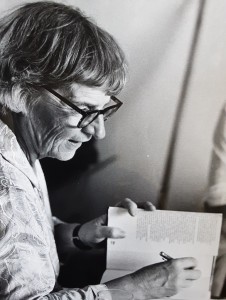

In a wonderfully lyrical essay on Finlay's connection to Orkney, critic and publisher Alistair Peebles points out a unique distinction of this work: of the many sculptural pieces installed outside of Finlay's home and garden at Stonypath, in the Pentland Hills south of Edinburgh, Gods of the Earth/Gods of the Sea was one of very few whose installation he travelled in person to observe – in the year before his death. This partly reflects the sudden lifting, during the mid-1990s, of the agoraphobia that had confined Finlay to the grounds of Stonypath for 30 years.

Ian Hamilton Finlay at the installation of 'Gods of the Earth/Gods of the Sea' on Rousay in 2005

Portland stone by Ian Hamilton Finlay (1925–2006) and Nicholas Sloan (b.1951)

But it also indicates the depth of emotional and creative connection he felt to Orkney, and to Rousay in particular, which he once described – with a nod to the unusual genre of art and literature that made him famous – as 'like a concrete poem, very particular, very realised'. His son, Alec Finlay, who cites this quote in a 2012 introduction to his father's work, suggests that it reflects Rousay's 'Platonic perfection': as if it were the ideal manifestation of a small, rugged Scottish island, bearing all the essential features, including a loch, mill, farms, ancient ruins, and ragged cliffs.

Ian Hamilton Finlay was a Scottish poet, artist and gardener whose most famous work combines elements of written language with elements of visual art, sculpture and environmental installation – all these aspects are present in Gods of the Earth/Gods of the Sea, whose title phrase is lifted from Virgil's Aeneid, an epic classical poem recounting the founding of Rome.

Finlay's most outstanding achievement was the creation of his Stonypath garden, which he christened Little Sparta, filled with poems inscribed upon a wide and culturally suggestive range of forms, from classical columns to watering cans. But he also worked across a range of media for different contexts and locations, from tiny artist's books to large site-specific sculptures across Europe and North America.

#littlesparta pic.twitter.com/eIdWOrH19M

— Little Sparta Trust (@LittleSpartaIHF) April 30, 2021

Despite Little Sparta's proximity to Edinburgh, the undulating hills around Stonypath separated Finlay like an ocean from the bustle of the Scottish capital. He was happiest in rural locations, and had a particular passion for islands, reflected both in his early biography and in the themes and forms that recur throughout his career. When he travelled to Rousay for the unveiling of Gods of The Earth/Gods of The Sea, it was, in a sense, a homecoming.

Finlay had first stayed on Rousay during the winter of 1955–1956, on a working holiday with his first wife, Marion. For the previous eight years, the couple had lived in Dunira, in rural Perthshire, where Finlay made his living as a labourer and shepherd while writing short stories and plays. Peebles speculates that the Finlays' Orcadian sojourn was an attempt to 'put some distance' between themselves and their tempestuous marriage. Referring to the mental health problems that affected his father throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Alec Finlay notes that '[t]he bounded nature of islands assuaged his anxiety'.

In 1959, Finlay returned alone to Rousay – he and Marion divorced shortly afterwards – to help repair the island's one, circular road while living in Sourin to the north, near the future site of Gods of The Earth/Gods of The Sea. The rocks for road maintenance were blasted and crushed at nearby Blossom Quarry, the subject of a poem which Finlay published in The Orkney Herald in 1959:

...as Blossom quarry it is known.

And who knows but the namer named it right?

Its flowers are on the hand with which I write:

Bent backs, sore bloody blisters it has grown.

(Blossom Quarry, Rousay, quoted by Alistair Peebles)

The work was blisteringly tough, clearly. But Finlay was happy on Rousay. He felt a bond with the landscape and local community, which ebbs through the poems he started to write there – he even called Orkney his 'birthplace as a poet'. Finlay's Orkney Lyrics, published in 1961 in The Dancers Inherit the Party, are full of references to the picturesque yet shrewd locals, from 'Peedie Mary' to 'Mansie'. The poems also establish a distinctive set of objects and themes – including fishing, boats and the relationship between land and sea – which, while already present in Finlay's writing, took on a new-found prominence from this point onwards.

Finlay was called back to Edinburgh after a few months to deal with financial matters related to his faltering marriage. He did not return to Rousay for 46 years. But the sense of peace and creative clarity he had grasped, briefly, in Orkney became an object of nostalgic yearning, perhaps imaginative reconstruction. Here is Poet, also from The Dancers Inherit the Party:

At night, when I cannot sleep,

I count the islands

And I sigh when I come to Rousay

– My dear black sheep.

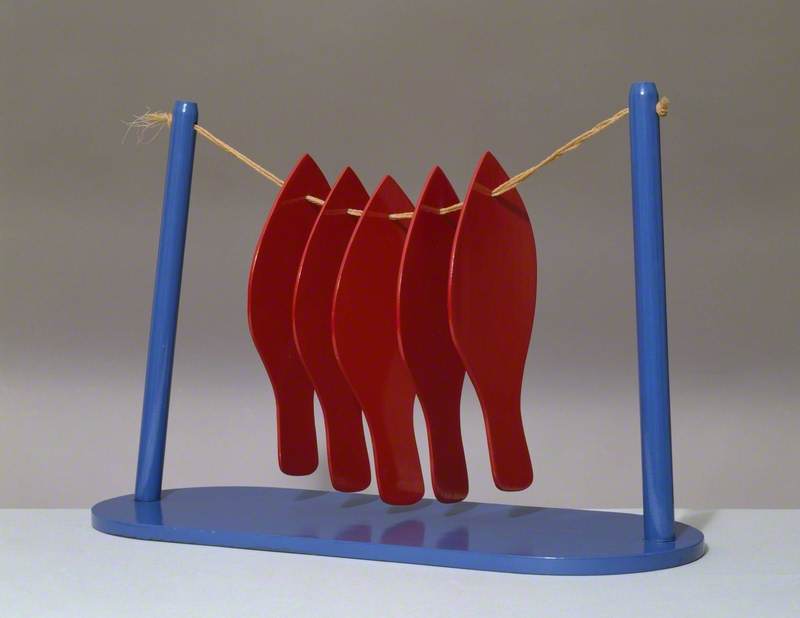

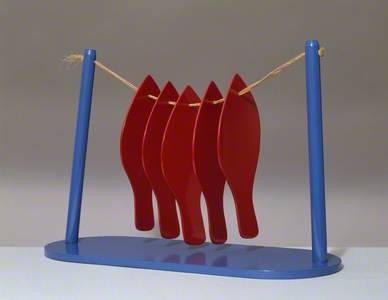

Around the time he was composing poems like these, Finlay was also creating what he called 'toys' – little wooden models of animals, boats, windmills and other childlike subjects, painted in bright model-aircraft enamels, many of which evoke the sights and sounds of his rural homes in Perthshire and Orkney. These include Fish, a row of red wooden fish on string suspended from little blue poles, recalling the strings of fish dotted across his earlier poems and stories.

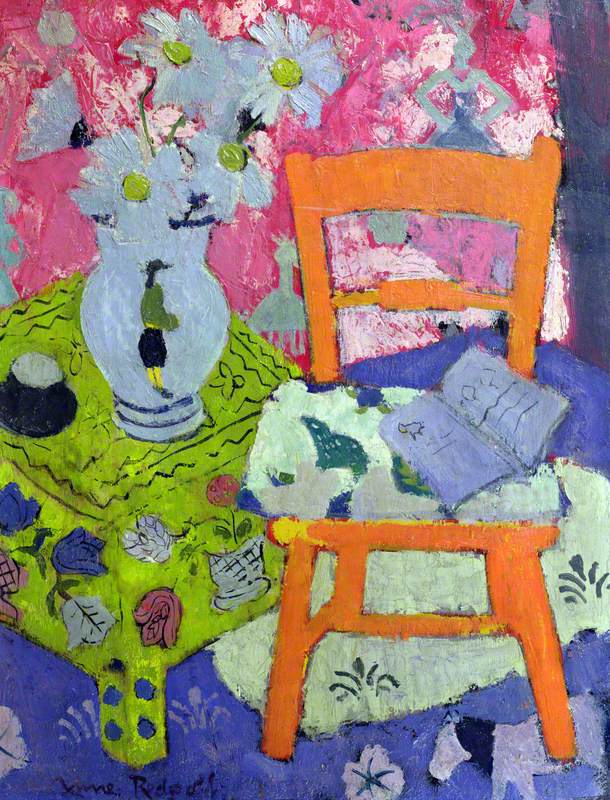

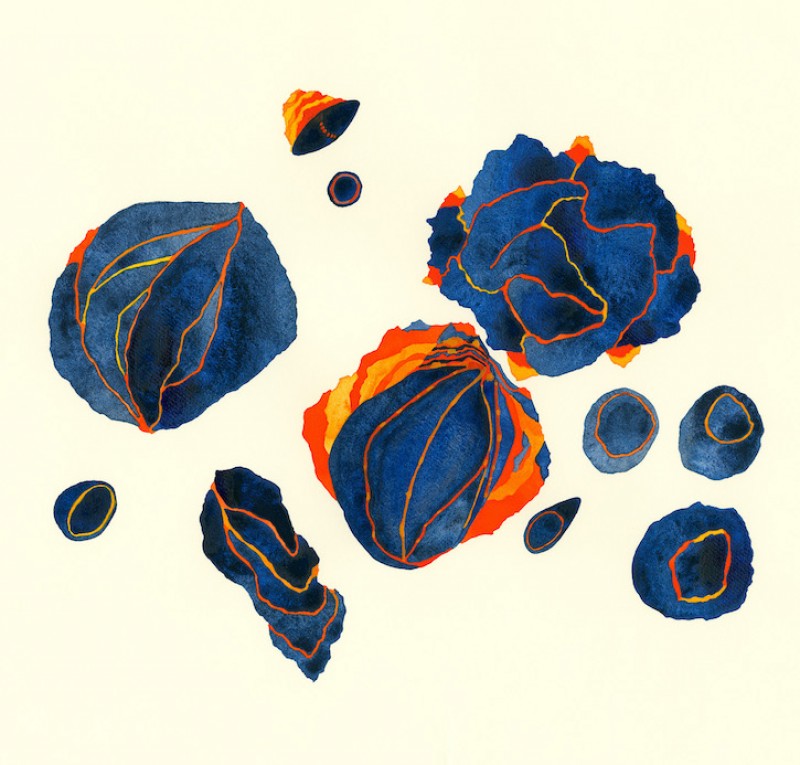

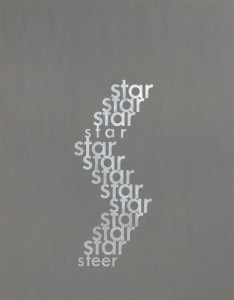

Then, in 1963, Finlay began creating what were called 'concrete poems', in which the visual appearance of language on the page was as significant as the linguistic meaning of the words. From there, it was a short jump to creating poems as little card sculptures, and brightly coloured posters. One of Finlay's works from this phase, the poster-poem Sea Poppy I, consists of a set of concentric rings made up of port codes – combinations of numbers and letters printed on the sides of boats, which indicate their place of registration, such as K47 and K161 – in different fonts and sizes. Notably, the two codes just referred to, found close to the centre of the poppy's petals, are of boats registered at Kirkwall, the largest town in Orkney. Finlay was continuing to evoke the island idyll of his memory.

In 1966, Finlay and his new collaborator and partner Sue relocated to Stonypath, then a semi-derelict farmhouse near the village of Dunsyre, around 25 miles south of Edinburgh. By this point, Finlay was already introducing more ambitious sculptural elements into his poetry, and was effectively becoming a visual artist. He had commissioned poems to be sand-blasted into glass, and would continue to do so across the 1960s and 1970s, including a red-lettered glass version of his 1966 poem Four Sails. (The descending letters and initials of this work – such as the SY, A, and K of 'roSY fAr blacK' – are, again, concealed port codes, alluding to locations such as Stornoway and Aberdeen.) But moving to the garden allowed him to realise his ambitions for three-dimensional poetry on a wholly new scale.

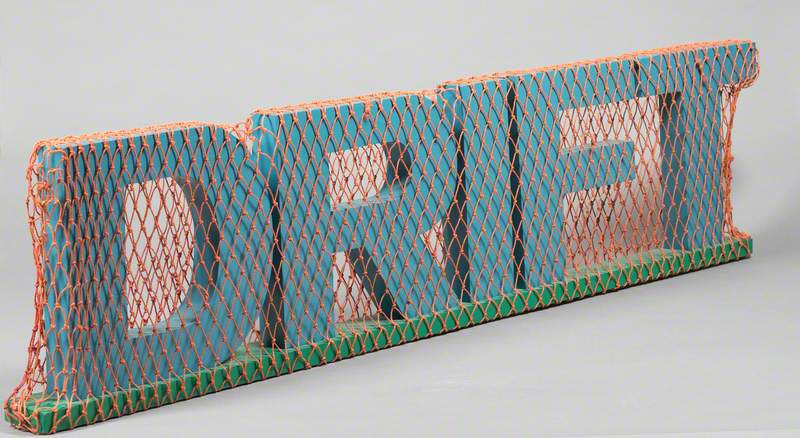

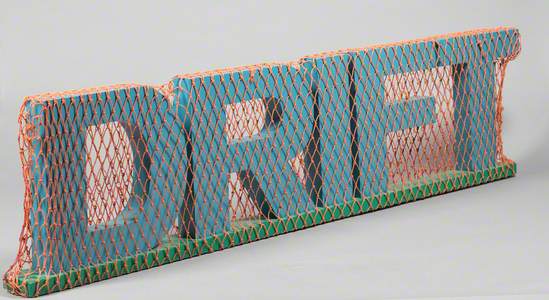

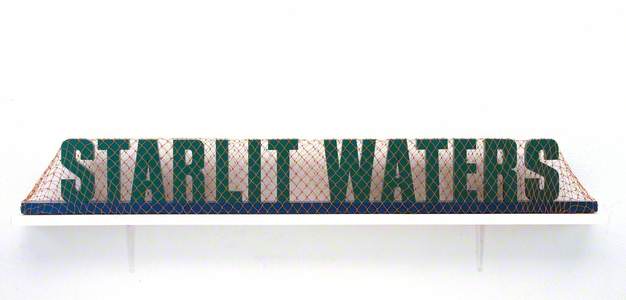

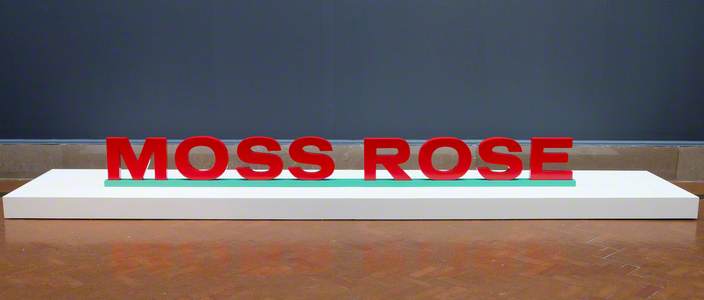

The grander scope of Finlay's vision comes across in his Boat Names and Numbers series, first exhibited in 1968. This project involved recreating boat names – like Drift, Starlit Waters, Moss Rose – as giant three-dimensional poems, some of them wrapped in fishing net, as if to capture the ambience of the absent vessel, bringing a maritime spirit to the artist's new, landlocked home.

Finlay's yearning for the sea, and for island landscapes, was exacerbated by the agoraphobia that had developed out of his anxiety. The boundaries of the garden became, in a physical if not imaginative sense, the boundaries of his world.

As Alec Finlay notes, his father sated his nostalgia by creating inland seas at Stonypath, damming streams to make ponds. 'He gave each of the ponds... a wee island,' Alec points out, 'and each island a poem' (realised as a sculpture). Sea and land also came together on the page, and on the carved surfaces that increasingly replaced the page in Finlay's imagination.

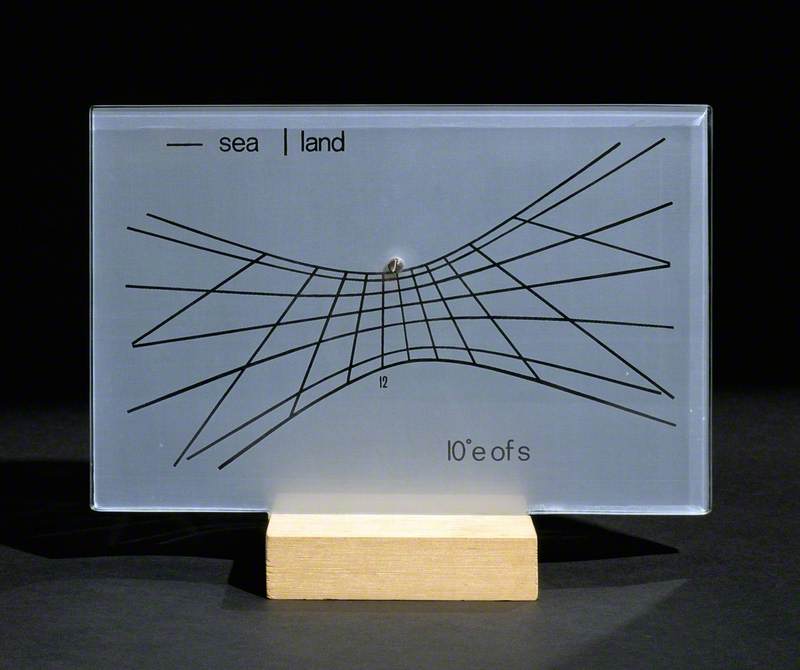

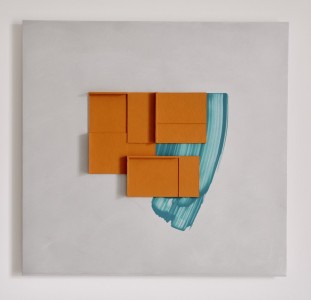

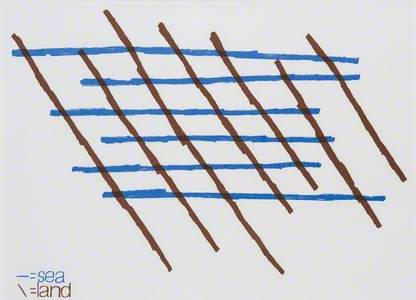

One of his favourite gestures to express that relationship was the crosshatching of horizontal and diagonal or vertical strokes, with a key reading 'sea and land' – as if they summed up two essential, harmonious yet opposing forces. Finlay's collaboration with Herbert Rosenthal, the poster-poem Sea/Land, exemplifies this idea.

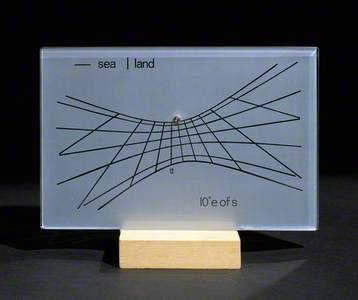

Later, when Finlay became more interested in classical themes, the sea/land grid melded in his mind with the etched markings found on sundials. So, we find the cross-hatched lines etched in glass doubling as hour markers on his Sea / Land Sundial.

The oceanic associations of these works almost always carry with them references to land, and to home: from the flowerhead of Sea Poppy I, to the port towns of Four Sails and the descending strokes of the sea/land motif. In short, though Finlay memorialised and venerated the sea, it was to be glimpsed from the safety of the shore. Finlay's vision was, in many ways, that of an islander, a coast-dweller, and it was on an island, Rousay, where much of the conceptual and emotional bedrock of his oeuvre was established.

It is fitting, then, that Finlay returned there just before his death, to unveil a work whose crosshatched surface pattern – above and below Sloan's central inscription – is surely another iteration of the sea/land design, a mnemonic for his yearning for Rousay. The work was sited, at the artist's request, on Kearfea hill, a little way from Blossom Quarry, where Finlay had gathered rock for road-mending half a century earlier. He returned to see the products of a different kind of labour realised, reunited with the source of his island memories at last.

Greg Thomas, writer and editor

'Marine: Ian Hamilton Finlay' at City Art Centre runs from 22nd May until 3rd October 2021 and is part of the Edinburgh Art Festival

This content was supported by Creative Scotland

Further reading

Alistair Peebles, 'Labour, Blossom: Ian Hamilton Finlay and Orkney' in Prose Supplement 7, 2011

Alec Finlay (ed.), 'Introduction: Picking the Last Wild Flower' in Ian Hamilton Finlay: Selections, University of California Press, 2012

Yves Abrioux, Ian Hamilton Finlay: A Visual Primer, revised second edition, Reaktion, 1992

Jessie Sheeler and Robin Gillanders, Little Sparta: The Garden of Ian Hamilton Finlay, Birlinn, 2015

Greg Thomas, Border Blurs: Concrete Poetry in England and Scotland, Liverpool University Press, 2019

Nancy Perloff (ed.), Concrete Poetry: A 21st Century Anthology, Reaktion, 2021