In his lifetime Handel Cromwell Evans (1932–1999) established his reputation overseas, in the USA, Europe and especially in Germany. His work is still little known in Britain. He was a truly international artist. His work is represented in collections throughout Europe and the Americas and in major institutions from the National Gallery of Jamaica to The Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Aberystwyth University School of Art Museum and Galleries holds the most comprehensive collection of his paintings drawing and prints and archival material spanning six decades of his life.

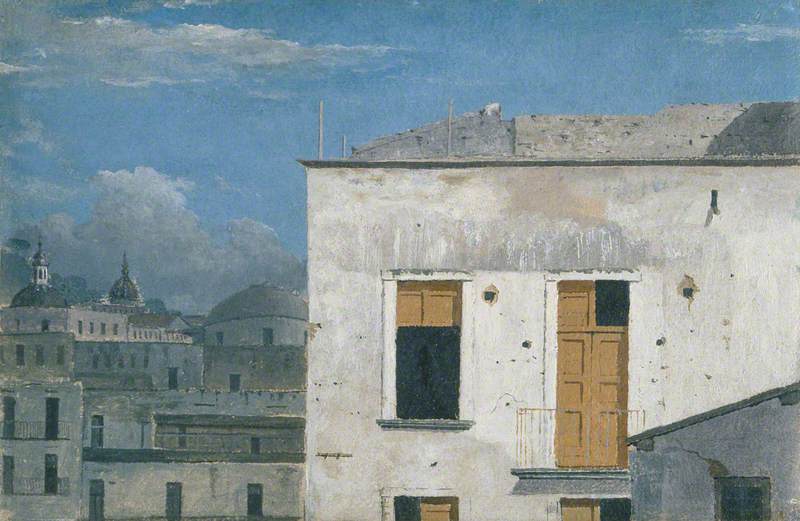

Central Fixation: The Employees Series

c.1985

Handel Cromwell Evans (1932–1999)

Handel was born in Pontypridd in 1932, trained at Cardiff College of Art 1949–1954, and subsequently made a living as a professional artist for the next 40 years, travelling widely and spending much of his time in the Caribbean, America and Germany. In the early 1960s he spent time at the British School at Rome and studied etching with Stanley Hayter at the prestigious Atelier 17 in Paris for a year in 1975.

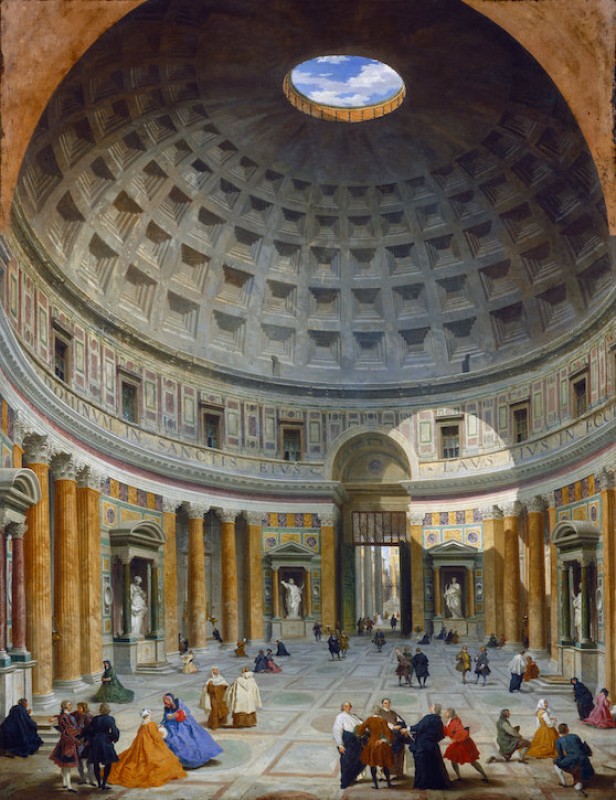

Devices: The Employees Series No. 92

c.1993

Handel Cromwell Evans (1932–1999)

Handel’s family and cultural background in Pontypridd was informed by music rather than art. His father Joseph was heavily involved in music and had a licentiate diploma from the London College of Music. He named Handel after George Frideric Handel; his son was born a few days before he was to conduct a choir of 2,000 voices singing the Messiah. Two years later Joseph gave up singing completely after being turned down for a scholarship.

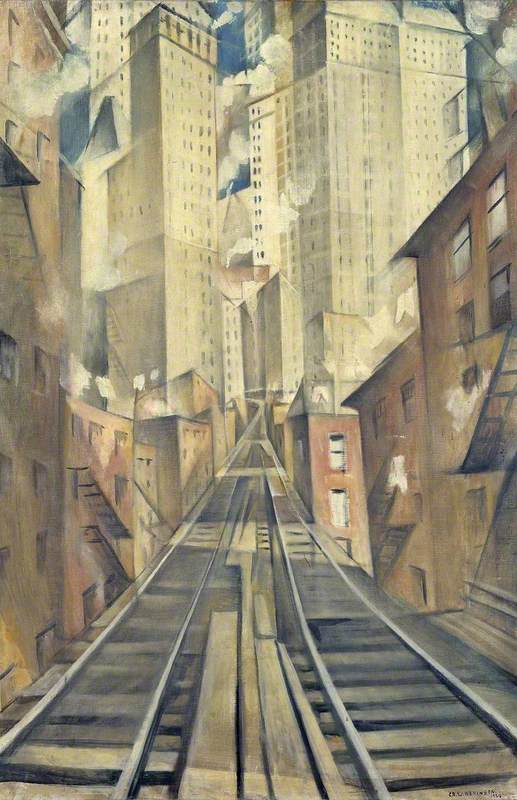

Enclosed Group 4: The Employees Series No. 78

c.1989

Handel Cromwell Evans (1932–1999)

As a teenager Handel had made the choice to pursue art as a career but his keen interest in and love of music continued. It informed his work throughout his life but not always in a direct manner. As a teenager Handel was taught piano by Clifford H. Lewis in Cardiff in exchange for giving his teacher’s young sons drawing lessons. Handel received a licentiate diploma from the Royal Academy of Music in 1958. In notes made in the early 1980s, held in the archive in Aberystwyth, he remarks on the life-long influence of Clifford Lewis’s teaching:

'My musical training, thorough and radical in its nature by reason of the greatness of Clifford Lewis, who taught me not only what I know of the art of the piano, but was also my mentor and to him I owe much of my development as an artist.'

He continued to practise and perform on piano and had two grand pianos, a Schiedmayer and a Blüthner in his house in Ramsgate. They are now in Aberystwyth University, bequeathed by his mother Marian Evans-Quinn, as part of the Handel Evans Collection and Trust Fund.

The importance of music in Handel’s life was undeniable but its relationship to his work, with a few obvious exceptions, is not always immediately apparent. In fact apart from the ‘musicians’ in The Employees Series and a few other works, the only explicit reference to Handel’s love of a particular composer is number 48 in the Employees Series, dedicated to J. S. Bach and the 48 Preludes and Fugues.

Courtyard I: The Employees Series No. 48

c.1986

Handel Cromwell Evans (1932–1999)

In his copious notes on his paintings in The Employees Series he writes:

'When inventiveness flags, or I need distance from a refractory picture, it is not to nature, even less to the examples of other artists do I turn, but to the keyboard.'

'With that aural structure/musical thought swimming about in my head, I find myself refreshed and energised to do battle with my optical/visual challenge/problems.'

Despite this indirect relationship, once we are aware of Handel’s love of music, it is difficult not to see his work in terms of musical structures – figure and motif, variations on theme, works in series – and in the rhythm and energy of his abstract forms in dissonant colours. It’s tempting to see this as a Kandinsky-like attempt to elicit a direct emotional response through abstract form and colour but it soon becomes apparent that Handel’s approach was much more subtle.

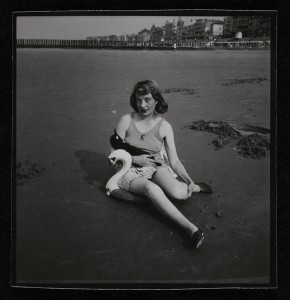

Musicians on a Platform: The Employees Monochrome Series

1985

Handel Cromwell Evans (1932–1999)

In both Musicians on a Platform and Six Musicians in a Room from The Employees Monochrome Series (mid-1980s) he uses a near monochrome palette to depict groups of a-sexual, faceless automata apparently playing instruments.

Six Musicians in a Room: The Employees Monochrome Series

1985

Handel Cromwell Evans (1932–1999)

These figures are forming and contained by their music-making machinery: sounding boxes and bodies, strings and sinews, conjunctions of pin-blocks, pegboards, fingers, joints and limbs. In other works in the series the gatherings of semi-human figures on a dais or platform suggest choirs, performers or chamber groups confined in the compositions and structures that also define them.

This technically 'grotesque' interpenetration of human beings and their material world is a frequently occurring figure and motif in Handel’s later output. The energy of this continual exchange is discernible in most of his finished work.

In an essay he wrote about his own painting Interpenetrations in 1989 Handel states that he 'wished the human and non-human elements to be inextricably involved with each other, just as mind and information are.'

The visual metaphor he strives for is the 'interdependent nature of the relationship between man and the growing mass of information with which his mind deals and on which it depends.' An approach which now seems to be ever more relevant to the way we look at, experience and interpret the world.

Neil Holland, Curator, Aberystwyth University