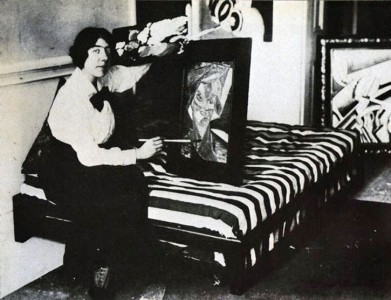

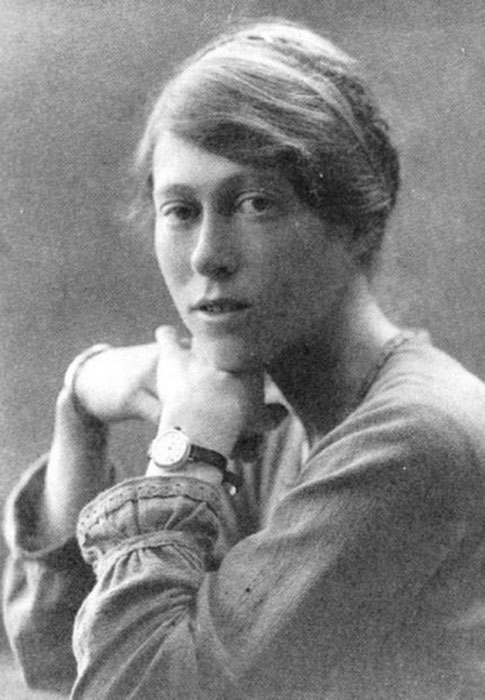

One of the co-founders of the literary and artistic movement Vorticism, Helen Saunders (1885–1963) lived an independent and bohemian life at the start of the twentieth century as a pioneering artist, writer and feminist.

Known primarily for her paintings, Saunders' work adhered to the Vorticist aesthetic of geometric abstraction. Later, her work would shift towards a naturalistic style, especially after the First World War when the Vorticist group disbanded. The exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery 'Helen Saunders: Modernist Rebel' (until 29th January 2023) presents drawings and watercolours that were recently added to the collection, which now holds more works by Saunders than any other collection in the world.

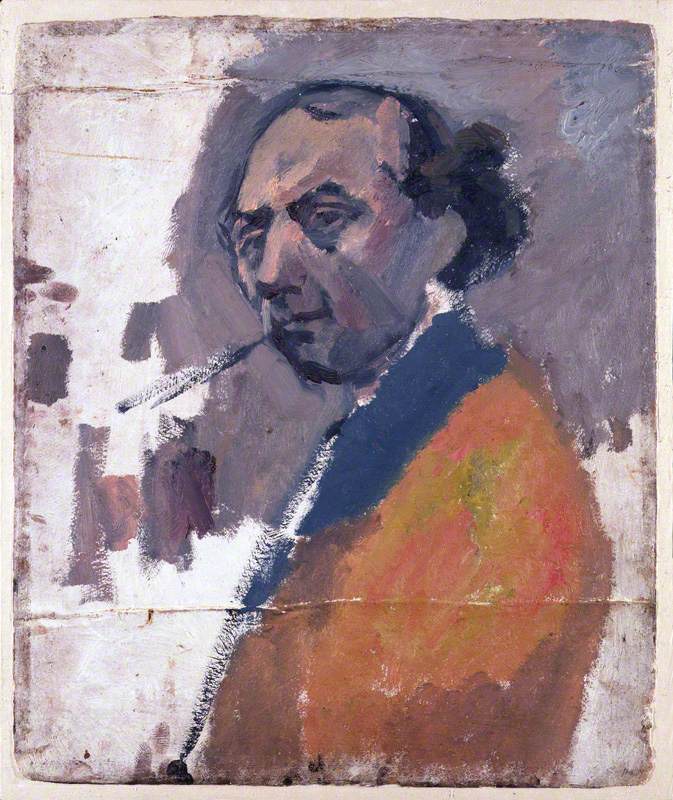

Helen Saunders

photograph by unknown

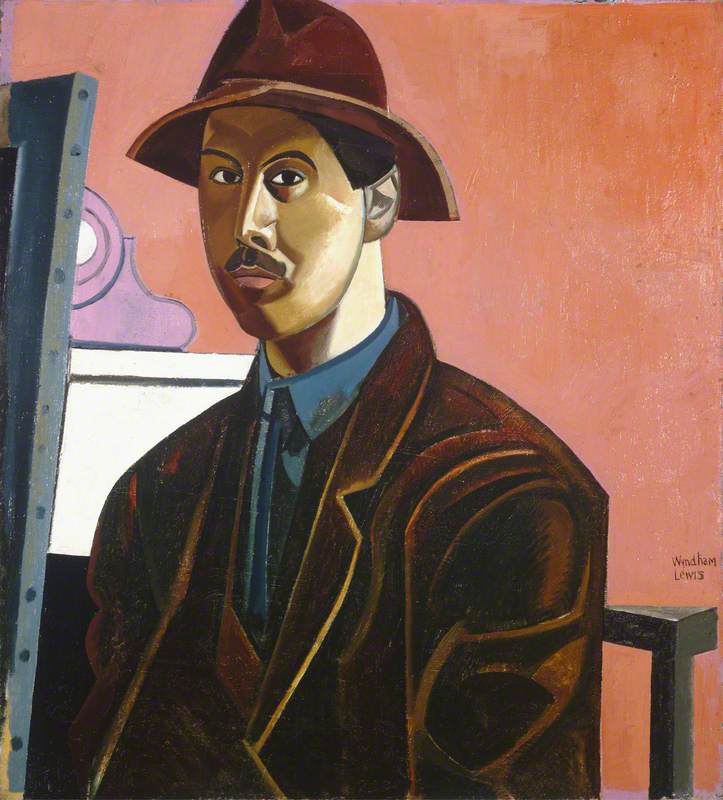

Alongside her friend Jessica Dismorr, Saunders became affiliated with the Vorticists through a connection with the artist Wyndham Lewis, an influential modernist who developed a provocative public persona both during and after his lifetime.

A member of the Camden Town Group between 1911 until 1913, Lewis was also affiliated with the Bloomsbury Group and the Rebel Arts Centre in March, 1914, from which Vorticism first emerged. Before joining the Vorticists, Saunders had mixed with Roger Fry's English Post-Impressionist group, a collective responding to experimental, painterly developments in France, most notably Manet.

Saunders had also trained briefly at the Slade School of Fine Art (which had allowed women to enrol from 1871), as well as the Central School of Arts and Crafts. She trained for three years under the artist and notable social activist Rosa Waugh Hobhouse (1882–1971).

So what were the aims of the Vorticists? The artists affiliated with the group sought to reconnect art to the societal effects of rapid industrialisation. They opposed forms of academic teaching and the sentimentalism attached to painting of the previous century. Like the Italian Futurists, founded by F. T. Marinetti in 1909, the Vorticists extolled the dynamism and violence of the machine.

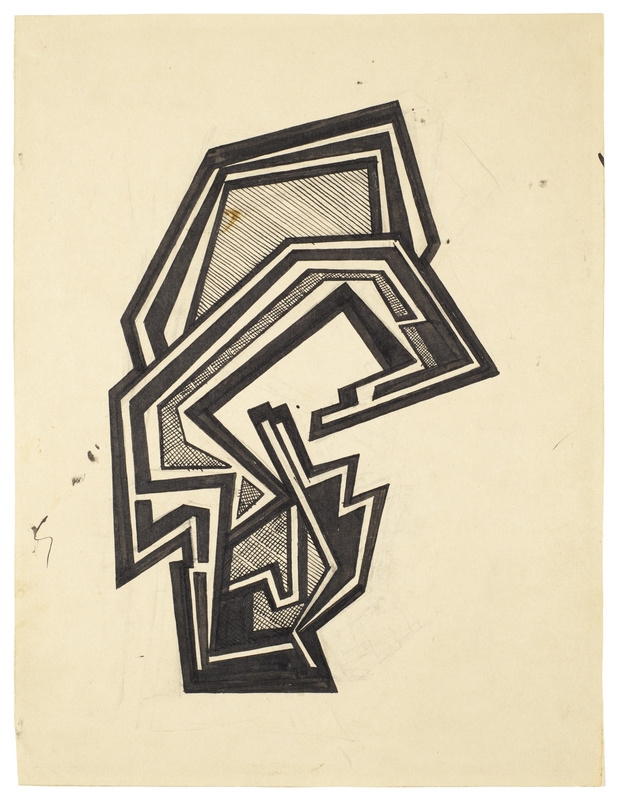

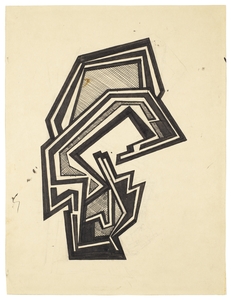

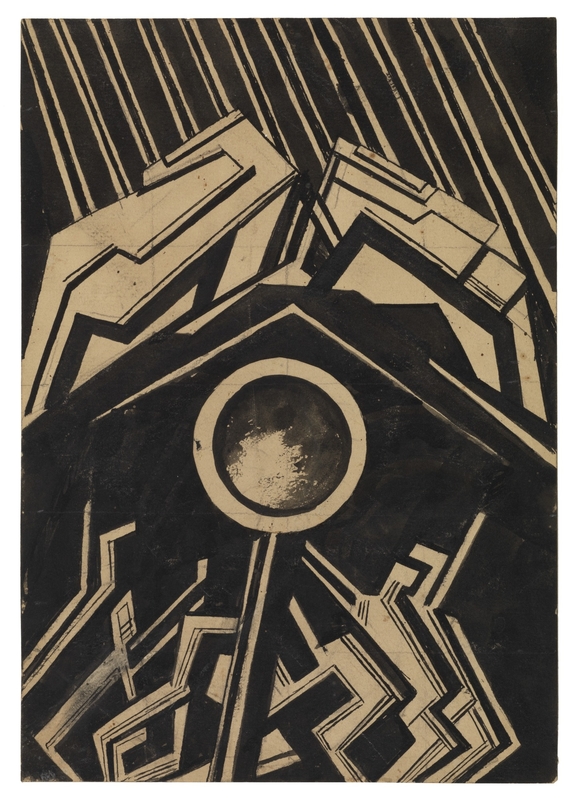

Vorticist Composition with Figures, Black and White

c.1915

Helen Saunders (1885–1963)

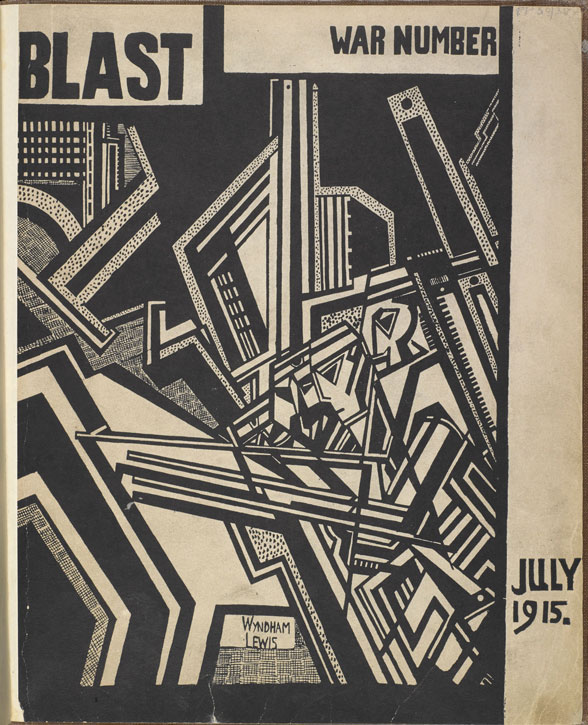

It was perhaps no coincidence that the group coalesced on the eve of the First World War. Their first manifesto, published in the short-lived magazine BLAST! stated:'BLAST First (from politeness) ENGLAND curse its climate for its sins and infection, dismal symbol, set round our bodies, of effeminate lout within.'

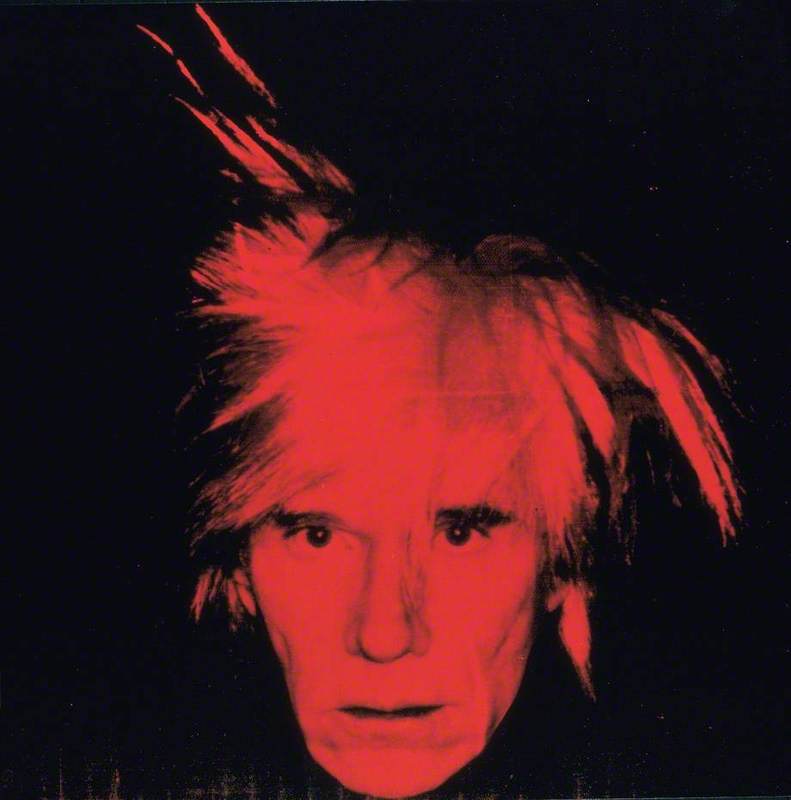

The cover of 'BLAST', July 1915

The fact that Saunders made a name for herself within a highly masculine environment reveals the respect she must have earned from her peers. As the Courtauld exhibition wall text reveals, Saunders left home for a poorer but more independent life in London – she worked anonymously as an experimental woman artist to 'spare her family embarrassment.'

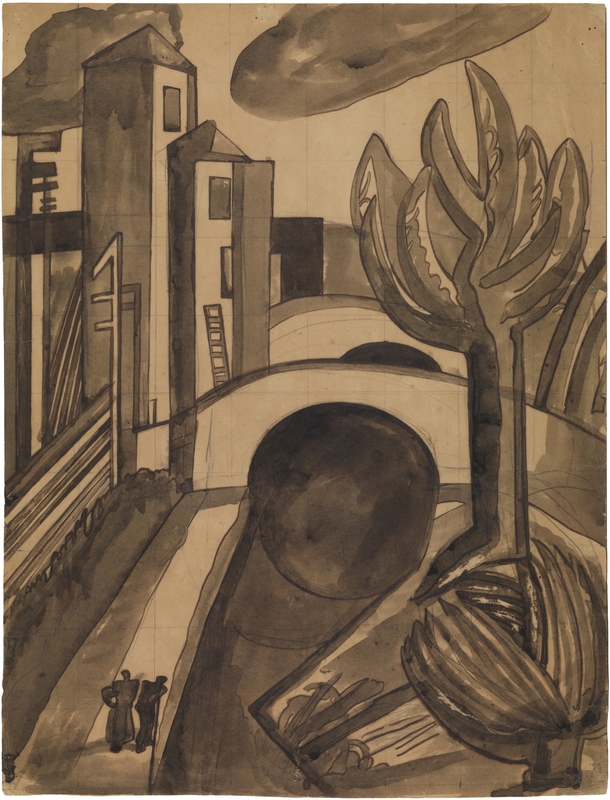

Vorticist Composition (Black and Khaki?)

c.1915

Helen Saunders

Tragically, and unlike male artists of Vorticism, her work fell into obscurity until the late 1970s, largely because few works survived – most of her early works were lost.

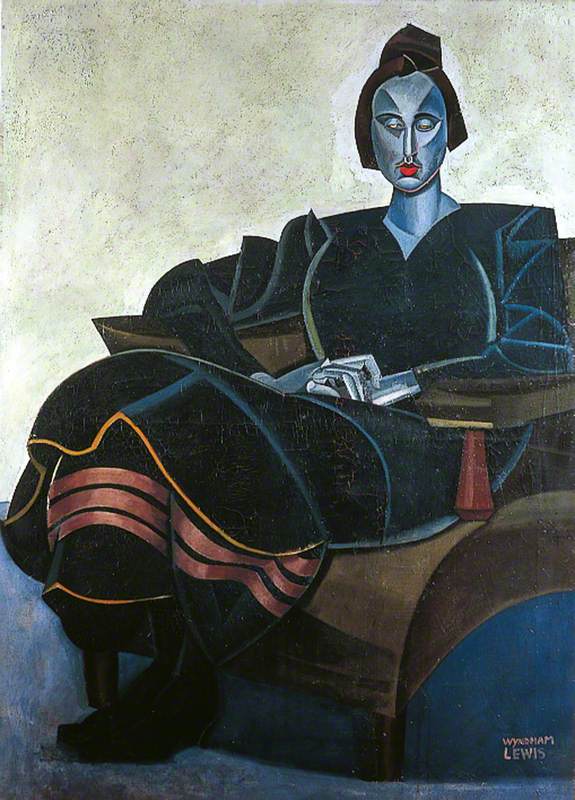

In fact, Saunders' descendant and principal biographer, Brigid Peppin, claims that Saunders was Wyndham Lewis's muse for over six years. But when their relationship became strained, he painted over her abstract work Atlantic City to create Praxitella, a portrait depicting the film critic and curator Iris Barry – Peppin claims Lewis 'left Saunders for' Barry.

A six-month analysis of the painting at the Courtauld revealed through X-rays that the painting had obscured the original work by Saunders, which you can read more about on the Courtauld's website. Peppin argues 'whatever the circumstances, artists do not paint over each other's works unthinkingly. It's most likely that Lewis obliterated Atlantic City in a calculated repudiation of Saunders' major contributions to the Vorticist project.'

Unfortunately, and like many women artists of that era, Saunders' route to success was indebted to her alliances with more influential male peers – a falling out with Lewis would further explain why she fell from the limelight.

Since the 1970s, her legacy has only been partially revived with exhibitions such as 'Radical Women: Jessica Dismorr and her Contemporaries' at Pallant House Gallery, curated by Alicia Foster. Although primarily focusing on the work of Dismorr, the show also emphasised the contributions of Saunders, including works such as this untitled drawing, alluding to the imprisonment of pro-suffrage activists.

Untitled ('Female Figures Imprisoned')

c.1913

Helen Saunders

In the case of Saunders and Dismorr, why would such highly educated and talented women – both of whom were affiliated with the concurrent feminist movement – attach themselves to a group with such a masculine, if not misogynistic, ethos?

Miranda Hickman, writing in Vorticism: New Perspectives, has argued that Saunders and Dismorr displayed what she calls a 'Vorticist feminism'. By this, she means that the women artists of the group internally and surreptitiously challenged its chauvinistic tendencies, by enlisting 'semiotics and imaginative strategies of Vorticist masculinity, both in their visual art and public affiliations, in order to pursue professional advancement as 'New Woman artists.''

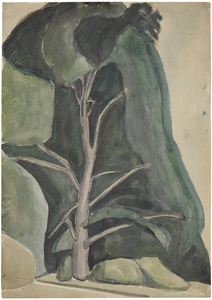

Vorticist Composition, Blue and Green

c.1915

Helen Saunders

Coined by the Irish writer Sarah Grand and later popularised by writers such as Henry James, the 'New Woman' represented a modern woman at the turn of the century, who lived independently and went against society's expectations. She typically believed in legal and sexual equality for women, and would have resisted Victorian, conservative attitudes towards gender.

Mother and Child with Elephant (1)

c.1914–1922

Helen Saunders

Lisa Tickner observed that women artists and activists of that era were under pressure to 'negotiate a set of inherited and interdependent categories of women', with female artists often adopting the identity of the 'New Woman'. Yet Tickner argues that while artists such as Saunders and Dismorr self-fashioned themselves as emancipated women, they also distanced themselves from the militant kind of feminism led by Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, echoing the Vorticists' ambivalence towards the movement.

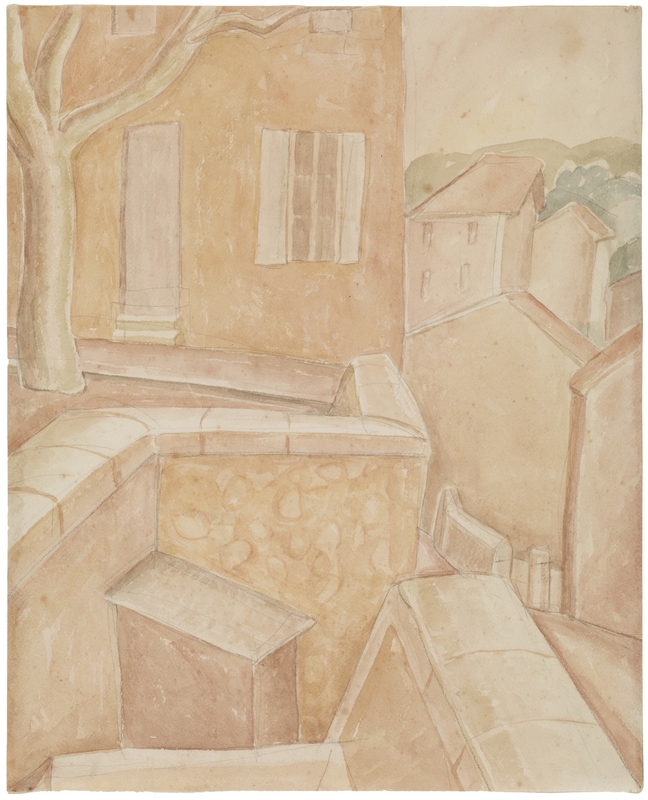

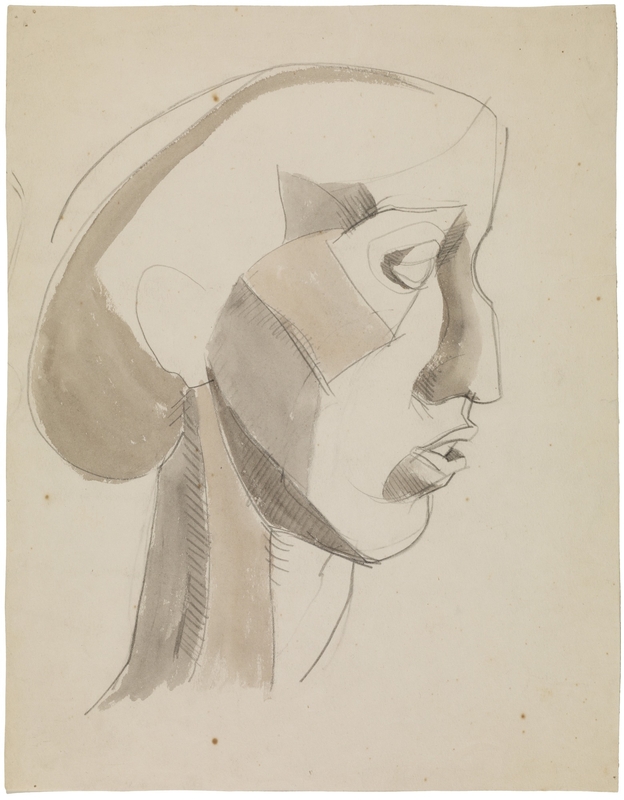

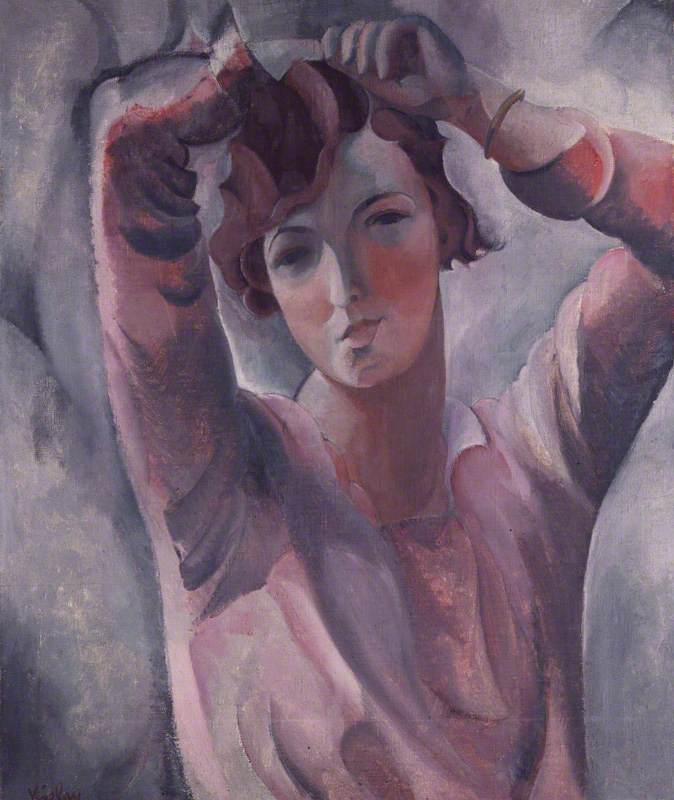

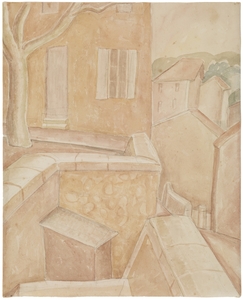

What is clear from walking around the exhibition at the Courtauld is that Saunders constructed her own aesthetic – perhaps informed by her experiences as a woman artist. She eventually turned away from the stylistic aims of Vorticism after the war, opting instead for her own figurative approach to painting. The exhibition notes that her later drawings and watercolours lacked the 'triumphalism' of earlier works, in the sense that violent destruction through aesthetic means dissipates in favour of more restrained, measured compositions.

Many of her works created at the start of the 1910s reveal a preoccupation with female subjects, as seen in Hammock (c.1913–1914).

In this graphite, ink and watercolour work on paper, a female figure lies in a hammock, though her tense body indicates she is suffering rather than resting; one hand is clasped to her breast and her face reveals an expression of acute anguish.

According to Peppin, this portrayal reveals a woman 'strung out between demands of convention, middle-class domestic propriety and the possibilities afforded by the avant-garde context.' Although angular and abstracted, Saunders still imbues the human form with expression – separating her work from the typical Vorticist aesthetic.

Saunders' early works also reveal her engagement with contemporary art in France, namely the influence of the Cubists. After the disbanding of the Vorticist group her subject matters would shift to landscapes, portraiture and still lifes, departing from the clean, geometric abstractions she previously championed. Instead, from 1920 onwards, Saunders adopted a more realist style.

She spent the rest of her life painting in relative obscurity and died from – what was believed to be – an accidental gas poisoning at her Holborn home on 1st January 1963.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.