This article has been kindly adapted for Art UK by Midlands Art Papers. Midlands Art Papers is a collaborative online journal, working between the University of Birmingham and 11 partner institutions to research and explore the world-class works of art and design in public collections across the Midlands. You can follow the project on Twitter: @MAP_UoB

Stormy Landscape with Blue and Red Figures by the Hungarian artist Károly Kotász was acquired by Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery in 1940. Donated by an individual named John Roberts, the painting has never been displayed at permanent or temporary exhibitions. This is not surprising: Kotász is hardly a well-known artist. People would be surprised to hear, even in his native Hungary, that for a few years around 1930 he enjoyed considerable international success. Who was this elusive artist, and why did his fame wane almost as suddenly as it had risen?

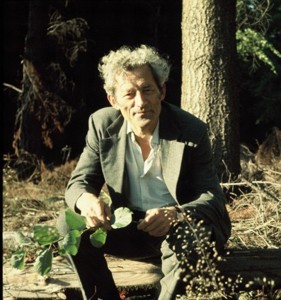

Károly Kotász was born on 4 November 1872 in Budapest in a poor, working-class family, and grew up in Rákoskeresztúr, a nearby small town. With the help of a scholarship, he trained as a wood engraver at the School of Industrial Design and went on to study at the Academy of Fine Art in Munich, and at the Julian Academy, a famous private art school in Paris. Returning to Hungary, Kotász taught at an art school while displaying his paintings at exhibitions. He bought a house in Rákoskeresztúr, got married, and had a daughter. His art brought him moderate success and he even had some one-man shows, but no one in Hungary could have predicted his international career.

In 1928, 50 paintings by Kotász were shown at the gallery at 12 Lützowplatz in Berlin. The works were subsequently displayed in Brussels, Amsterdam, and London. The driving force behind the European tour was Kotász’s nephew, Károly Kemény, who organised his exhibitions abroad and took care of public relations. Kotász’s exhibitions were often opened by Hungarian consuls and other official figures, but their success reached far beyond diplomatic circles. Newspapers and art magazines all over Europe published

Modernist art is fraught by an ideal of constant progress, and once the evolutionary narrative that included Fauvism, Cubism, Surrealism and all subsequent -isms became widely accepted as the ‘true’ modernist tradition, more conservative artists such as Kotász fell by the wayside.

Although he was celebrated in several major cities across Europe, Kotász himself could not be present. Since his youth, his mobility had been restricted by an unspecified condition that seems to have worsened over time. The painter who had once made the long journey to Munich and Paris now became sedentary. According to contemporaries, on a typical

That said, even if he was unable to meet his international fans, he must have seen some of the reviews. Kotász’s art ʻexults in a riot of colour and atmosphere’ and ʻcan get beauty out of an old lady standing by a flock of geese in sunny, windy weather, and dynamic drama out of peasants battling against a scirocco’, wrote the British critic Trevor Allen. Another critic called him ʻone of the most advanced of modernists’. In Apollo Magazine, Herbert Furst described him as a highly original artist, who built on the art of predecessors such as Rembrandt van Rijn, Francisco Goya, Antoine Watteau or Adolphe Monticelli, but used this tradition to create his own, individual style.

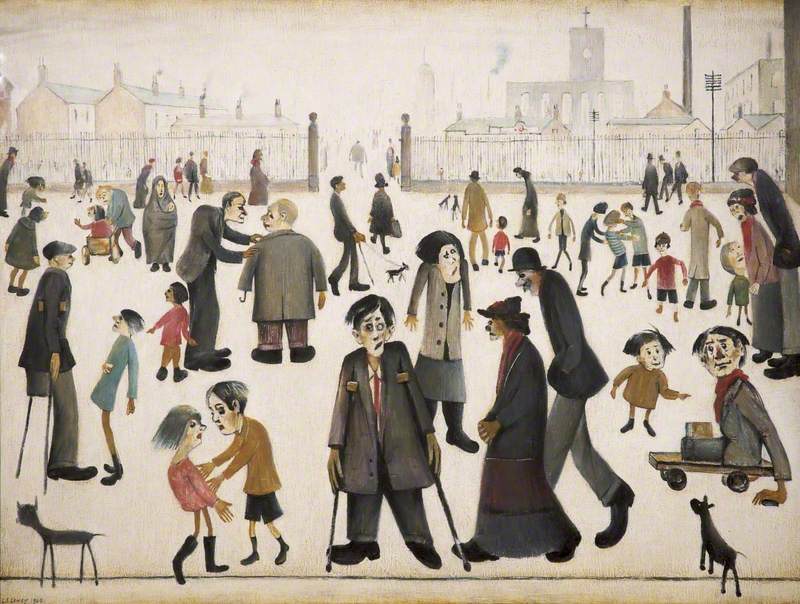

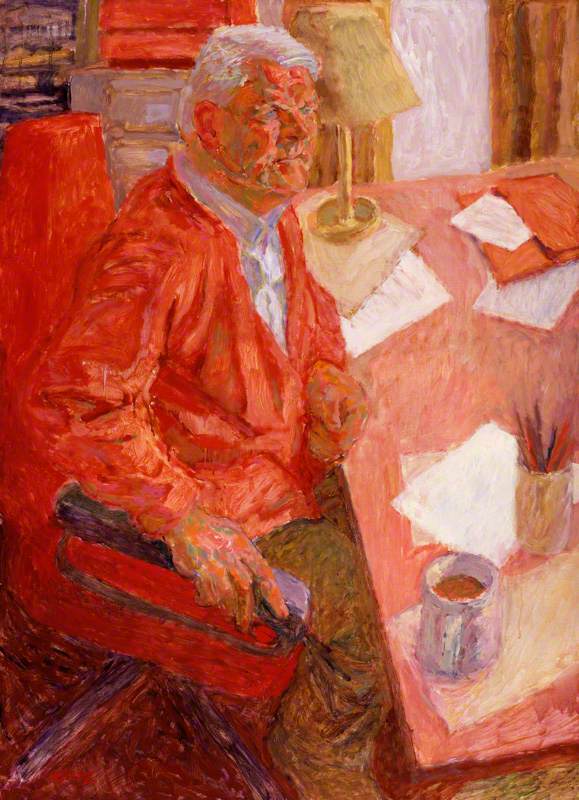

Kotász’s style was, indeed, distinctive, and the painting in BMAG is a characteristic example. As in most of Kotász’s pictures, the setting is rural: a group of women dressed in folk costumes are returning home from church. The sky is cloudy, signalling an imminent storm. The palette is dominated by soft greens and greyish blues, and there are not many contrasts, yet the blue and red of the figures shine with a gem-hard brilliance. Kotász used a personal technique he had developed himself: he applied thick layers of paint and scraped them with a knife creating a rough surface, which nevertheless appears harmonious when seen from a bit further away.

Kotász’s paintings are undoubtedly pleasing to the eye, but how to explain his stellar success and subsequent fall into oblivion? Based on the reviews published at the time, two – not mutually exclusive – explanations can be proposed for the former question. First, by following a Post-Impressionist aesthetic, but always remaining in the realm of the figurative, Kotász appealed to a certain kind of moderately modernist taste. He bowed to the tradition hallmarked by Manet, Monet, Van Gogh and Cézanne, but did not venture towards more contested terrains, thereby providing art lovers with solid reference points, as well as evidence of his own individual creativity. Second, as an artist from a land outside the Western European art world, he represented an exciting novelty. His homeland and his rural subjects were often exoticised by critics. His disability, due to which he remained distant from his audience, only added to the mystery.

Why, then, was he forgotten? This might be a logical consequence of the same factors. Modernist art is fraught by an

The story of Kotász’s career poses provocative questions about the ups and downs of fame, as well as about the external factors that influence us when we think we are merely judging paintings by their formal qualities. His name may have fallen into oblivion, but that oblivion is not impenetrable, thanks to the museums that have preserved his works. The paintings by Kotász in collections around Europe serve as poignant reminders that by documenting the past, museums also present it to be rediscovered, challenged and rethought.

Nóra Veszprémi,

Further reading

Nóra Veszprémi, 'Gambling on Genius: Károly Kotász, Stormy Landscape with Blue and Red Figures (c.1928)', Midlands Art Papers, Issue 1, 2017