On the side of what is now a boxing club on Lowood Street in Shadwell is a nationally significant, partially remaining piece of public art: a 1985 mural titled Across the Barrier by Shanti Panchal and Dushka Ahmed.

Across the Barrier

(Shadwell Anti-Racism Mural, GLC) 1985

Shanti Panchal

I visit this partially visible mural often to think of circular diversity initiatives and the erasure of experiences. I also look to the mural as a reminder of the dominant cultures within the arts sector in the United Kingdom – in England, in London – that have fragmented movements of anti-racism and movements on the margins. These fragmenting experiences mean new generations feel as if they must start the fight – for recognition, value and understanding – all over again.

This dominant culture has also assimilated the language of inclusion – a facilitated and mediated aspiration for inclusion of the marginalised but through a hyper-exclusive (in terms of ethnicity and class) set of gatekeepers. These gatekeepers are the new preachers of diversity. That the Shadwell mural symbolises this is partly why I consider it nationally significant. The other argument for why I see national significance in this piece of public art is a more objective point: this is the only remaining mural of an important public art commissioning programme by the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1984.

Across the Barrier

(Shadwell Anti-Racism Mural, GLC) 1985

Shanti Panchal

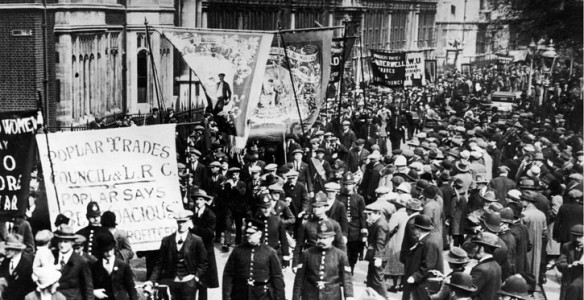

The mural is emblematic of a social, cultural and – in this case – also political ecology of the 1980s that brought focus on anti-racism movements and the experiences of racism across British society. This ecology was galvanised and pressured into action by younger generations who grew up in the shadow of post-colonial racisms and Enoch Powell-inspired activations of this racism to their grandparents, parents, siblings and themselves: from workplace exclusions and housing discrimination to street assaults and murders. These activations often went with justice unresolved and perpetrators never held to account.

Across the Barrier

(Shadwell Anti-Racism Mural, GLC) 1985

Shanti Panchal

In 1984 the GLC, through their Ethnic Minorities Unit, commissioned an anti-racist mural campaign. This was part of a wider initiative the GLC had been galvanising through the early to mid-1980s, branded 'London Against Racism'. This coalesced with movements of nuclear disarmament and other political positions from the stark left that existed in contrast to the Thatcherism of the central government. I appreciate the research and work that Dr Hazel Atashroo has done within this context and whose work dives deeper into setting the scene.

Whether it's circumstance or conscious intervention, the fact that the mural's bottom half is hidden is remarkable in its symbolism.

The anti-racist mural commissioning programme delivered four murals across London, selecting young artists of colour – most of whom are now established artists with work in national collections. It was some of the first public arts funding that many of these artists received, artists who worked outside of the mainstream art sector (a sector that still has been playing the game of catch-up in inclusivity). As well as the Shadwell commission, Gavin Jantjes was assisted by Tam Joseph to create a mural in Brixton, Keith Piper and Chila Kumari Singh Burman were commissioned in Southall, and Lubaina Himid and Simone Alexander in Notting Hill.

Almost every mural created as part of the programme has disappeared. This reminds me of the heightened and charged conversations about monuments and statues in the public realm that have been at the forefront of culture-war conversations in recent years. As compared to the impact of the removal of certain statues, the removal of anti-racist public art has taken place without note.

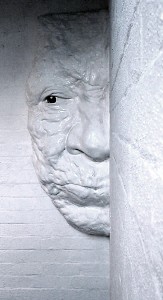

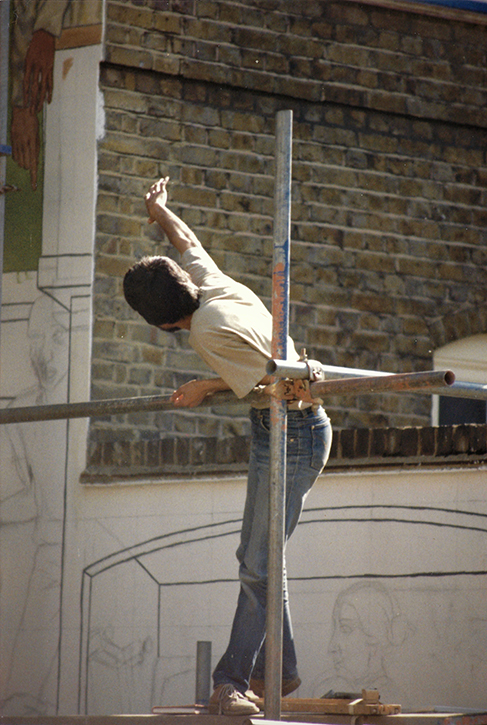

Shanti Panchal working on the Shadwell mural in 1985

Shanti Panchal was commissioned after his work echoed through the relevant voices to the Ethnic Arts Sub-Committee through his participation in a handful of group shows across London, including the Whitechapel Galleries open. He was working as a graphic designer at the time, after studying fine art, first at the Sir J. J. School of Art in Bombay, then at the Byam Shaw School of Art in London. Panchal then brought on artist Dushka Ahmed as an apprentice to develop and deliver the mural.

This commission was, like many of the commissions in the programme, the first major access to public art resources that Shanti Panchal received since his initial British Council scholarship to study in London in the 1970s. In taking the commission, Panchal lost his job as a graphic designer due to the time commitments that were needed to complete the mural in its final stages. This was a moment that he recounts as a blessing in disguise, which turned his faith into being a full-time artist.

Across the Barrier

(Shadwell Anti-Racism Mural, GLC) 1985

Shanti Panchal

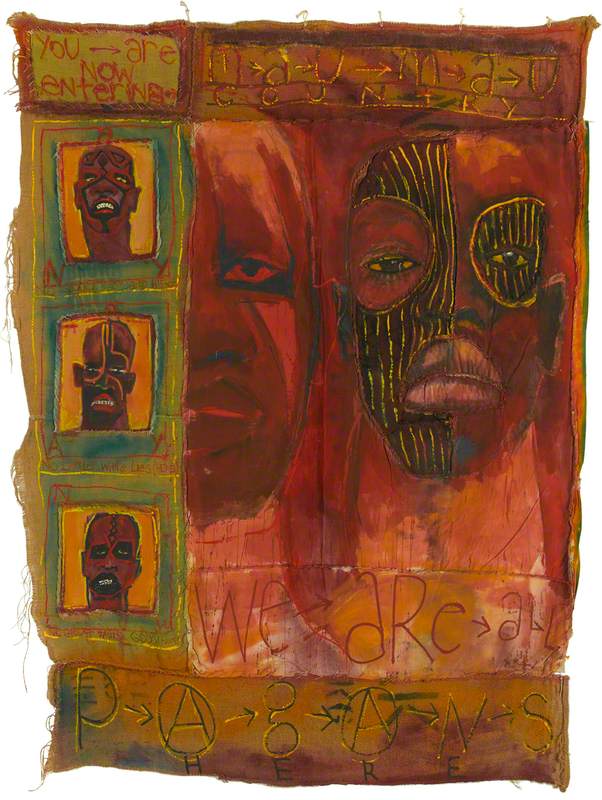

Across the Barrier tells a story in three acts, from the ground up. The first act is no longer visible, hidden by a block of maroon paint that sealed this part of the story in a tomb forever sometime in the 1990s or 2000s.

Across the Barrier

(Shadwell Anti-Racism Mural, GLC) 1985

Shanti Panchal

This first act showed a Bengali-Muslim family watching Margaret Thatcher on television in a house, with a man in a suit pointing in their direction in conversation with their neighbours. The man in the suit symbolises the bureaucratic prejudice of xenophobia that manifests in the blaming of immigrants for society's problems. This was not the original image in the concept designs. Shanti Panchal spent a lot of time researching the mural by connecting it to the experiences of residents in the Teviot Estate in Poplar which had a significant Bangladeshi population.

The early draft images of the mural depicted racist thugs in acts of violence on the street instead of a man in a suit campaigning against immigrants. Through community consultations about the mural, this visceral image was decided too triggering to the reality of 'Paki bashing' – the extremely violent, but far more common than most people remember, experience that many faced in the 1970s and 1980s. The theme of this first part of the story represents the barriers, the prejudice and the racism experienced by so many.

Across the Barrier

(Shadwell Anti-Racism Mural, GLC) 1985

Shanti Panchal

The next stage of the mural – the middle image, which is still visible – is harmony: coming together in class solidarity to break constructed barriers.

Across the Barrier

(Shadwell Anti-Racism Mural, GLC) 1985

Shanti Panchal

The final part, the top of the mural, with people of all backgrounds and ages riding a dove, represents a universal spiritual experience that, according to Panchal, people of all faiths and none strive towards: a spiritual harmony beyond concepts of worldly barriers.

Across the Barrier

(Shadwell Anti-Racism Mural, GLC) 1985

Shanti Panchal

Whether it's circumstance or conscious intervention, the fact that the mural's bottom half is hidden is remarkable in its symbolism. The cultural memory of Britain celebrates, and rightly so, in the incredible diversity and flourishing of cultures that happens across the country – especially in a city like London. London symbolises so much of the inclusive heart of the country. But there is often an amnesia regarding the levels of racism that were experienced in England. These experiences echo post-colonial reality today, alongside the symbols of hope and inclusion.

The art sector holds a great mirror to this, with many of the artists commissioned on this project, and many who fought for recognition, now lauded by institutions, curators and other gatekeepers who represent the very same cultures and demographics that put the barriers of exclusion to them as artists in the 1970s and 1980s.

Across the Barrier

(Shadwell Anti-Racism Mural, GLC) 1985

Shanti Panchal

I look to this mural as a nationally significant piece of art – a reminder that whilst working towards inclusion is about celebrating harmony and the ideals of being a plural society, the memory of the hostility, erasure and lack of accountability to historic racisms is essential to be acknowledged to create authentic, inclusive and understanding futures.

A mural like this tells this story and should be protected on this basis.

Hassan Vawda, Doctoral Researcher at Goldsmiths/Tate