Currently on display until 28th October 2018 at the National Heritage Centre for Horseracing and Sporting Art, Newmarket, is a rare exhibition of works by the animal painter James Ward (1769–1859), a lesser known artist.

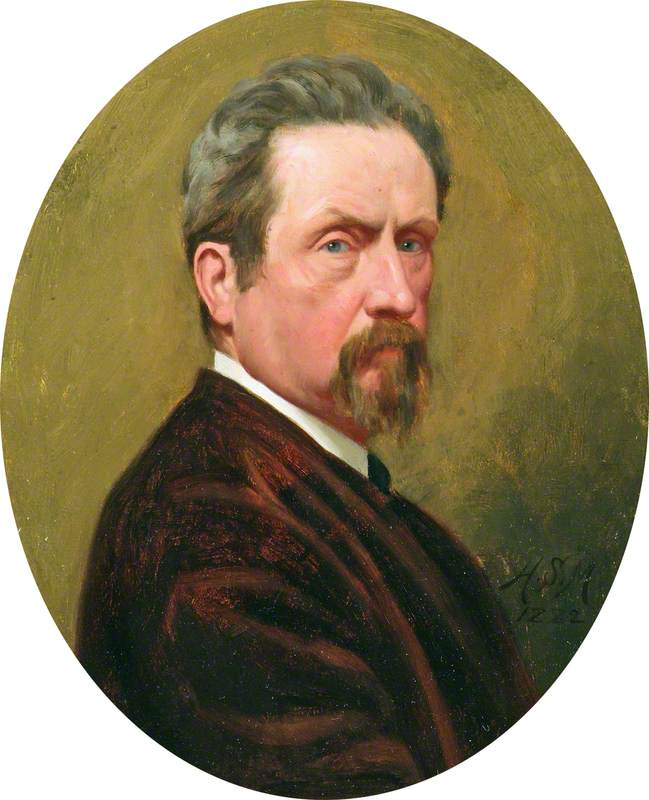

Spanning the reigns of George III, George IV, William IV and Queen Victoria, Ward was a prolific artist who focused from an early age on the depiction of animals, principally livestock. Known as the first painter of animals after George Stubbs’s death in 1806, he retained this reputation until the emergence of Sir Edwin Landseer in the 1830s. Greatly influenced by the spirit of Romanticism which swept across Europe, he was one of the first artists to imbue the animals he painted with feelings. He attempted to convey animals as sentient beings and to illustrate their emotions in the same way as humans. The exhibition demonstrates this through a rich selection of material, with works from various stages of his ambitious career.

James Ward was born in London and his father was a fruit merchant. He was apprenticed to his elder brother, William, an accomplished mezzotint engraver, and his sister was married to George Morland, both of whom influenced Ward. He began producing finely worked prints, most of which he bequeathed to the British Museum and by 1807 was Painter and Engraver to the Prince of Wales. He was also commissioned by the Agricultural Board to draw every breed of livestock in the United Kingdom to inform farmers and act as a classificatory system for the better understanding of breeding.

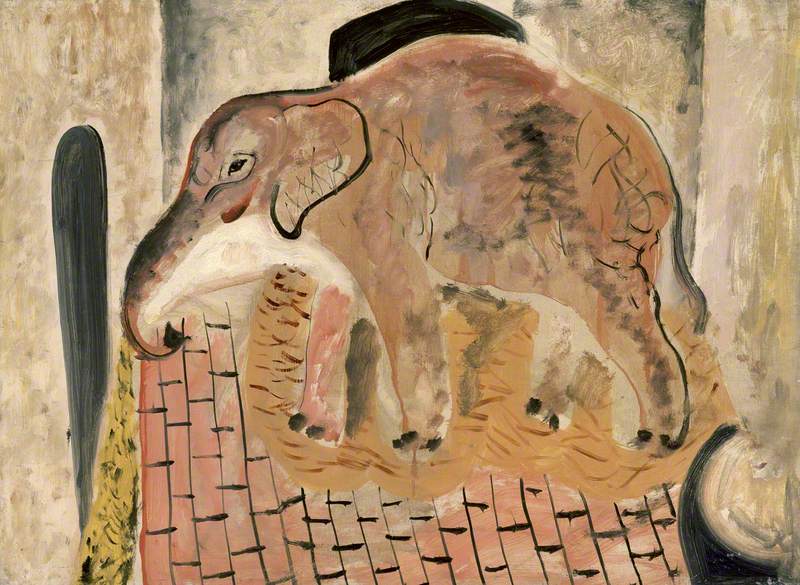

Unfortunately the publisher Boydell went bankrupt and the commission was abandoned, not before Ward had produced thousands of sketches of farmyard animals, including sheep, cows, pigs. These drawings informed his work throughout his life and he continued to seek out different species from Indian cattle called zebu, Spanish asses, a wide variety of birds as well as the more exotic animals such as rattlesnakes, many of which would be found in his patrons’ menageries. Beef demonstrates not only his anatomical precision in this study of the carcass of a prize ox but also his technique in the thickly applied brushstrokes conveying muscle and texture.

By the early 1790s, Ward had gravitated from printmaking to oils and showed his proficiency to the extent that he was elected to the Royal Academy in 1811. A Fight between a Lion and a Tiger (1797), exhibited at the Royal Academy, shows a debt to Stubbs and the popular interest in the romantic wildness of nature.

By contrast, A View in Tabley Park signifies a debt to Constable in this apparently quiet pastoral scene of cattle drinking by a lake at nightfall in the grounds of Sir John Leicester’s estate in Cheshire. The tranquillity of the scene is belied by the fact that the scene was drawn just before a thunderstorm with the crackle of electricity in the air. On closer inspection, the cattle are alert, listening, waiting for the abrupt change in the weather, half fearful by the water.

The study of horses played a particular part in Ward’s career and he produced the extremely successful set of fourteen lithographs, A Series of Lithographic Drawings of Celebrated Horses, based on oils he painted. The racehorse 'Dr Syntax', for instance, won 36 races between 1814 and 1823 including seven consecutive Preston Gold Cups, five Lancaster Gold Cups and five Richmond Gold Cups. All the horses were shown in appropriate landscapes often alluding to the perceived calm prosperity of Britain in contrast to the turbulence of Europe after the Napoleonic Wars.

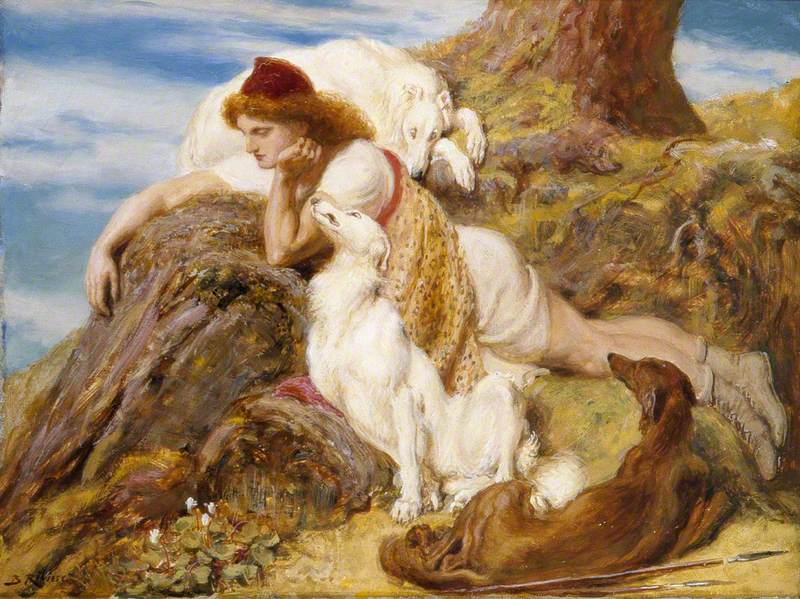

While these works, most of which depicted racehorses and highlighted their power, strength and therefore speed, Ward was also experimenting with studies of the Arab horse. This breed fascinated Ward due to their nervous action and fine bone structure and he frequently drew them, capturing in dextrous lines the detail of sinews and tendons. At the same time, he imbued them with emotions and asked the viewer to engage with the concept, novel at the time. This is shown in L'Amour de Cheval, in which two elderly Arab horses are shown in a loving relationship in a swirling landscape dominated by the twisting branches of an overhead tree.

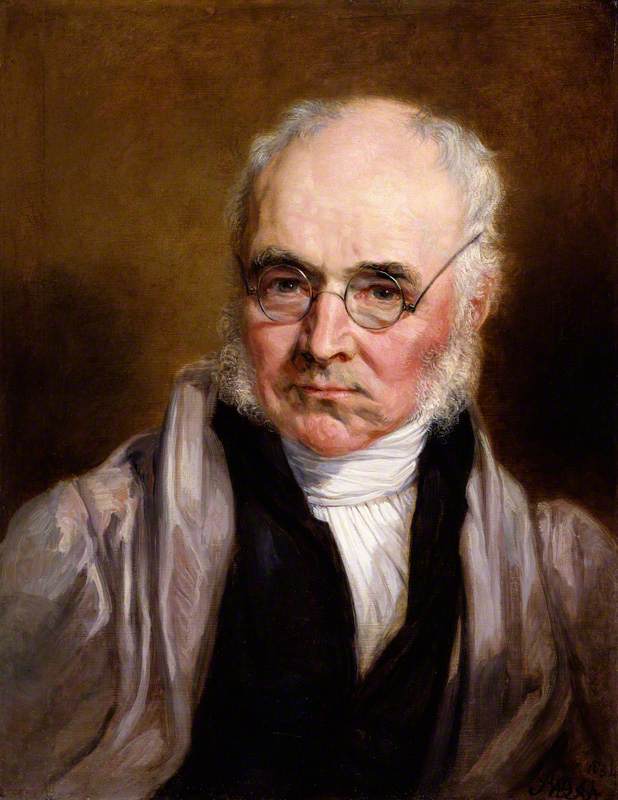

By the late 1820s, Ward had become increasingly absorbed by a religious intensity and he was very preoccupied with the tenets of Aesop’s Fables in which animals spoke and acted like humans in order to teach and convey moral lessons. It is probably therefore not surprising that John Bunyan, author of The Pilgrim’s Progress, was the favourite author of this great animal painter.

Pat Hardy, Head of Collections, Exhibitions and Displays at the National Heritage Centre for Horseracing and Sporting Art