'… Some say Casablanca or Citizen Kane – I say that Jason and the Argonauts is the greatest film ever made…' – Tom Hanks

Ray Harryhausen's career as an animator spanned from the 1940s through to 1981, and he produced fifteen classic films which continue to astound to this day. However, for many, it is his 1963 epic Jason and the Argonauts which is the byword for his cinematic genius. An adaptation of the classic Greek myth, brought to life through some of the most incredible special effects ever seen on screen, Jason's popularity endures over 60 years after its initial release.

By 1962, Ray had established himself as a filmmaker responsible for producing incredible stop-motion animation. Having worked on early experiments and short films throughout the 1930s and 1940s, his first role on a feature film was as First Assistant on 1949's Mighty Joe Young. Working alongside his mentor, legendary King Kong animator Willis O'Brien, it is estimated that Harryhausen was responsible for around 90% of the film's stop-motion sequences, which went on to win an Academy Award for best special effects.

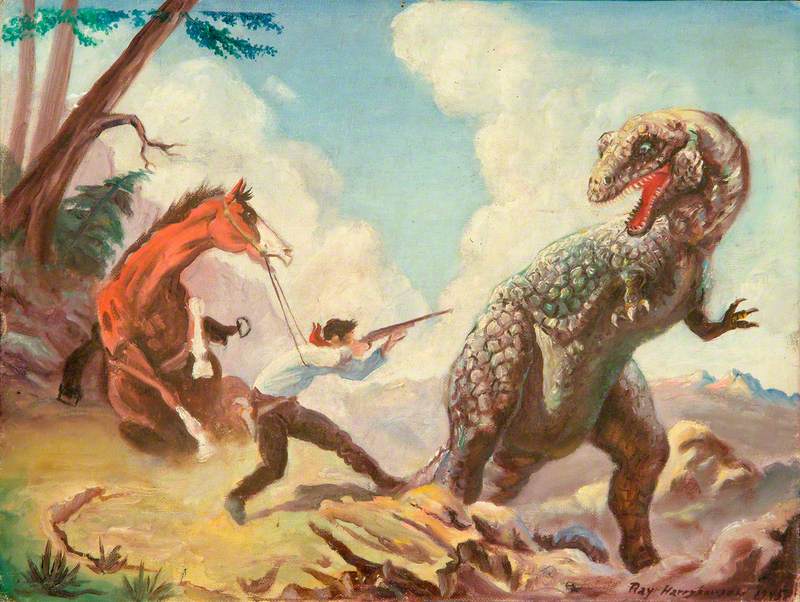

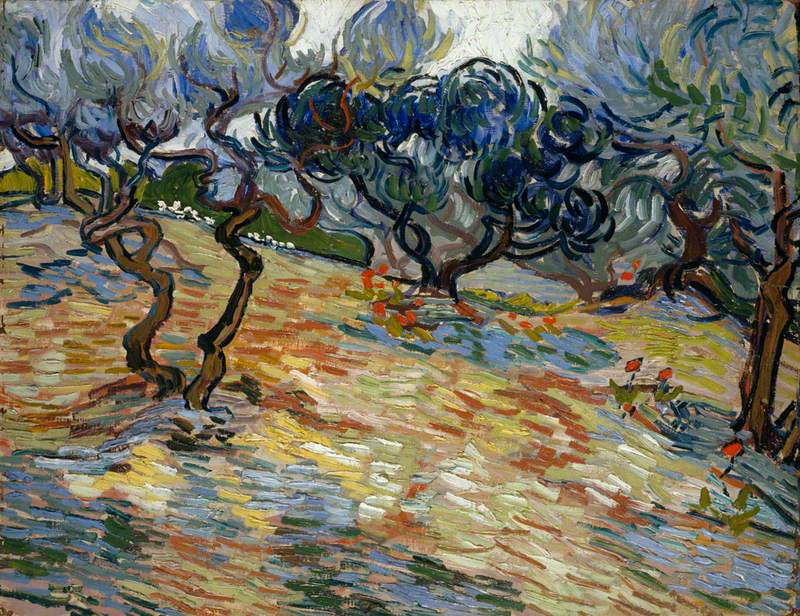

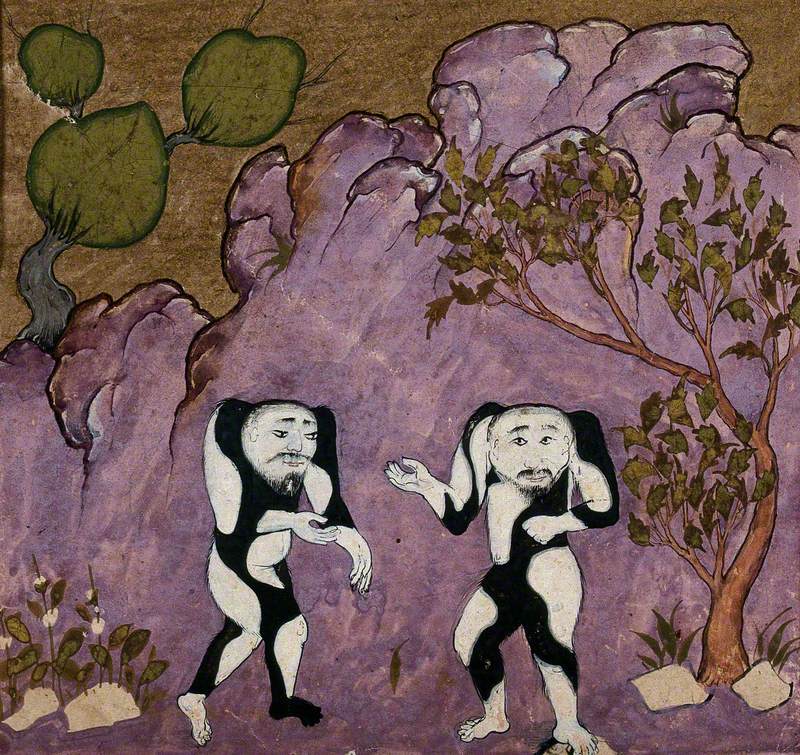

The 1950s saw Ray establish himself as a solo animator, developing a technique which came to be known as Dynamation. He produced a series of black and white 'creature on the rampage' movies, all of which showcased his incredible creations battling against the contemporary world. However, it was 1958's The 7th Voyage of Sinbad which changed the trajectory of fantasy cinema. The first major stop-motion film to be shot in colour, The 7th Voyage saw a menagerie of mythological creatures tell a story adapted from Arabian Nights mythology.

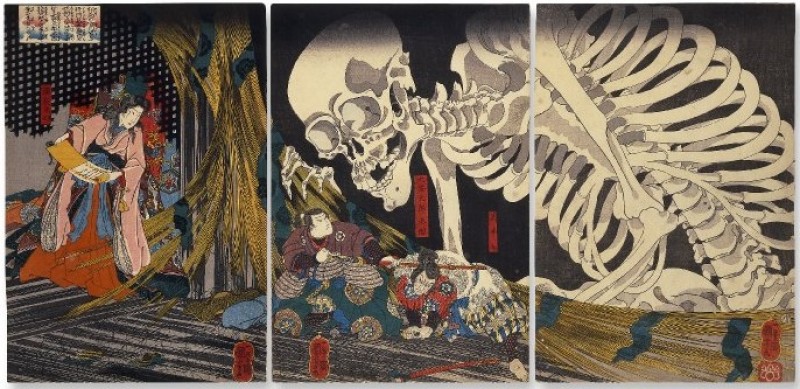

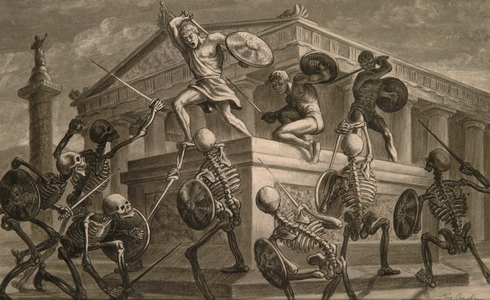

Sinbad Fights the Skeleton

1957

Ray Harryhausen (1920–2013)

The 7th Voyage of Sinbad was a huge success, and led to Ray working on adaptations of classic literature – The 3 Worlds of Gulliver and Mysterious Island. However, Ray was keen to revisit the inspiration that mythology provided for on-screen creations never before seen by audiences. In 1961, he wrote a rough outline for a film based on the classic tale of Jason and the Golden Fleece.

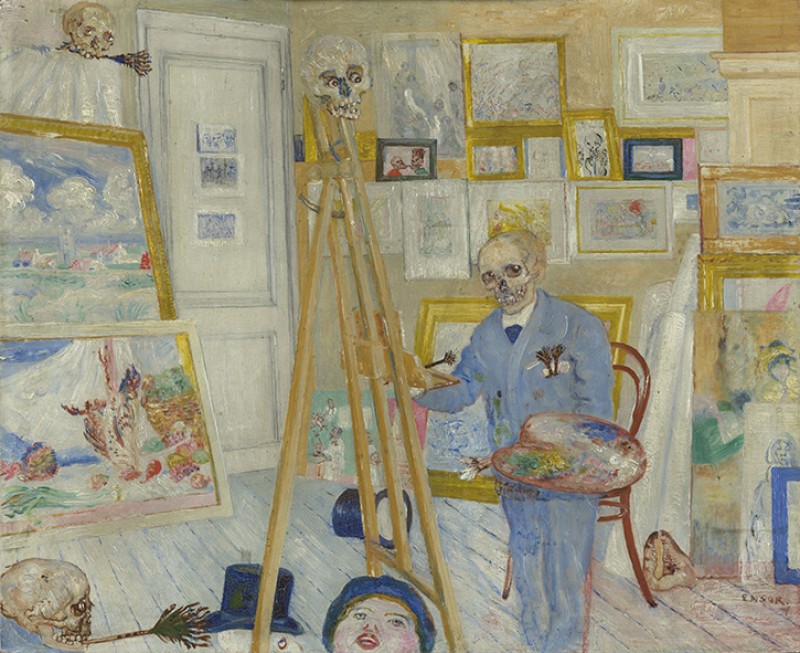

Jason Defends the Golden Fleece from the Skeleton Army

1962

Ray Harryhausen

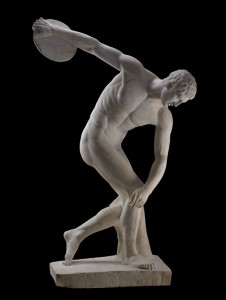

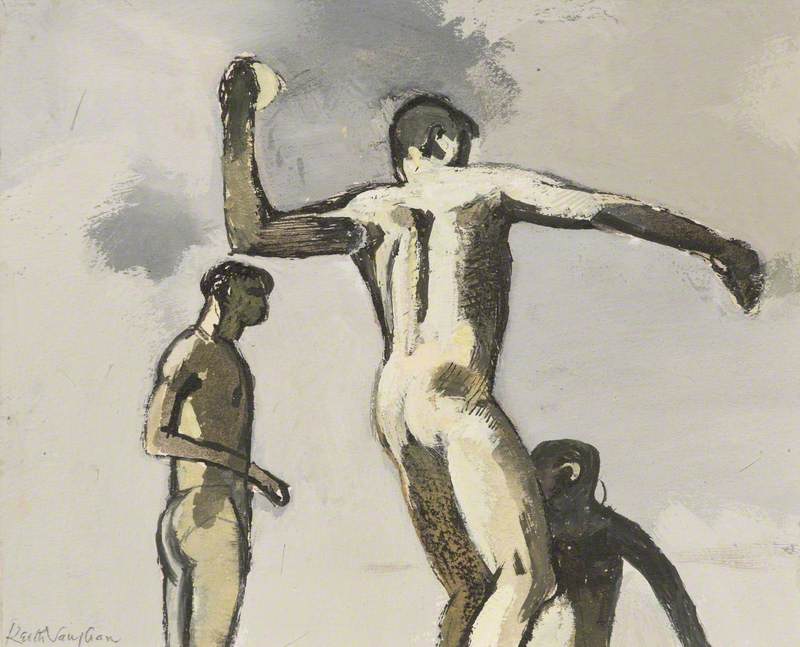

Screenwriter Beverley Cross expanded upon Ray's initial ideas to create a workable 90-minute picture, through which Jason and his crew would battle against the machinations of the gods, alongside a series of incredible creatures. Of course, such mythology in its original form is not suitable for a commercial film project, and Ray was occasionally criticised for rewriting such timeless tales to suit a cinema-going audience. Decades later, the film's influence can be seen upon a generation of archaeologists and classicists, with Ray's artwork being displayed alongside some of his favourite nineteenth-century painters at galleries such as Tate and the Scottish National Gallery.

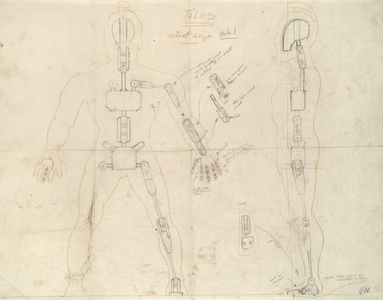

The film's first piece of stop-motion animation sees the implacable bronze giant Talos come to life and attack Jason's crew. Ray was presented with the difficult task of portraying emotion and anger through the unchanging features of this enormous creature – as such, the character is infused with a deliberately stilted animation style, portraying the character's cold focus and inherent danger. The actual model for Talos stands at 17 inches tall, however, on screen, he represents by far the largest of any of Ray's creations, dwarfing the human characters that he pursues.

The Talos model seen here has recently been restored by Foundation conservator Alan Friswell, who worked directly with Ray to ensure that future generations could see his original models in person. Indeed, every remaining screen-used model was showcased at the landmark 2020 exhibition 'Ray Harryhausen: Titan of Cinema' at the National Galleries of Scotland, accompanied by a biographical book of the same name by Harryhausen's daughter and Foundation trustee Vanessa Harryhausen.

As with all of Ray's early movies, the metal armatures inside each latex model were constructed by his father, Frederick Harryhausen. A machinist at trade, Frederick would build according to his son's detailed specifications. Sadly, Ray's father would pass away shortly after the animation was completed for First Men in the Moon in 1964.

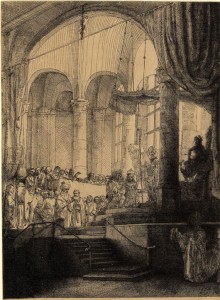

After encountering Talos, Jason's quest then moves to the plight of Phineus, blinded by the gods and tormented by the demonic Harpies. Played by future Doctor Who actor Patrick Troughton, the sequence was filmed amongst the ruins of an actual Greek temple at Paestum. It is important to note that Ray Harryhausen was more than just an animator, and was responsible for creating artworks that would provide the basis for such set pieces. This artwork offers an excellent example of how Ray would bring unique visions to life from his imagination through to the big screen.

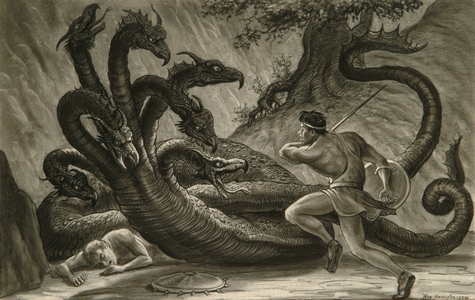

The seven-headed Hydra stands as one of Ray's most complicated models, with an intricate internal armature containing moving parts for two tails, a large body and seven individual heads.

During the time that Ray was working, there was no way of checking video footage for progress or mistakes until the end of a day's work, and sequences such as the Hydra's would essentially need to be animated in one continuous session. Ray would often comment that a phone call or similar interruption could be massively distracting as he attempted to track the movement of seven individual heads from memory.

The destruction of the Hydra leads to what has since been regarded as one of the most incredible cinematic sequences of all time. The battle between Jason's Argonauts and Ray's skeleton army represents a feat of imagination and technical skill which continues to impress to this day. Having showcased a single living skeleton in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, Ray pushed himself to create an even more complex and demanding sequence for Jason.

Jason and the Argonauts Skeleton Fight

1962

Ray Harryhausen

The 'Children of the Hydra's Teeth' sequence took Ray over four months to animate. With the requirement to match so many moving parts to the movements of live-action actors, he was able to complete less than a second of footage per day. These original skeleton models have survived particularly well, being constructed of liquid latex dipped in cotton wool and then wrapped around a thin metal armature.

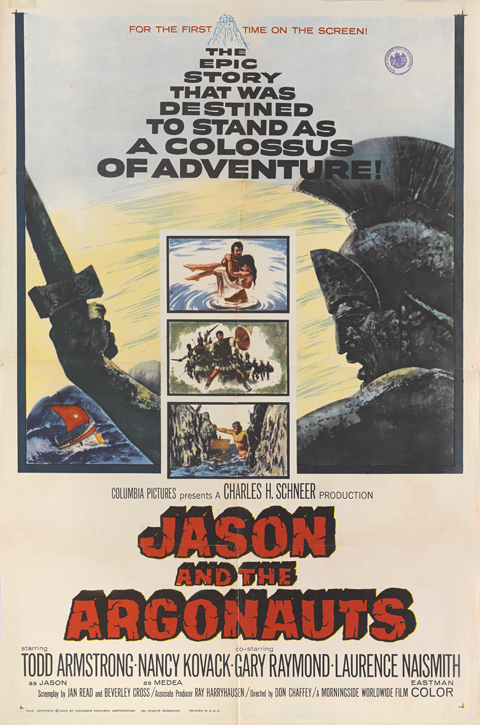

Although Jason and the Argonauts was a modest box office success upon its initial release, the film gained legendary status in the years that followed. Regularly shown on television during public holidays, the movie has entertained and enthralled generations of film fans.

Poster for 'Jason and the Argonauts'

Ray Harryhausen's final film Clash of the Titans was released in 1981; showing a great deal of foresight, he went on to establish The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation in 1986. The Foundation are today responsible for taking care of Ray's incredible collection of original models and artworks, including many pieces from Jason and the Argonauts. At some 50,000 items, it is estimated to be the largest animation archive outside of the Walt Disney collection.

Ray's legacy continues with The Ray Harryhausen Awards, which aim to celebrate the work of contemporary artists and filmmakers. This year's awards will take place at the Cameo Cinema in Edinburgh on June 29th, which also marks Ray's birthday. Most appropriately, the winners' announcement will be followed by a special 60th-anniversary screening of Jason and the Argonauts – a perfect celebration of Ray Harryhausen's creativity and enduring influence on today's cinematic landscape.

Connor Heaney, Collections Manager for The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation

Many of Ray Harryhausen's artworks are available as prints from the Art UK Shop, along with gifts featuring his iconic creations. All purchases support The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation.