The Leith-born artist John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961) was a leading figure of the Scottish Colourists, though he was essentially self-taught. First trained as a naval surgeon, Fergusson decided to abandon medical pursuits for a bohemian life as a painter.

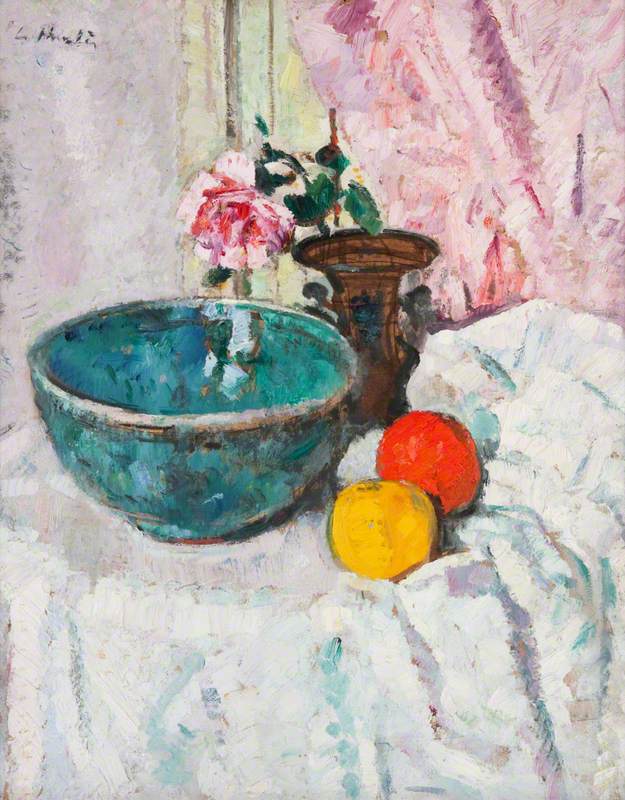

A painter and sculptor whose artistic style shifted as frequently as his geographical location, Fergusson's love for travel took him to Africa and across Europe, where he mingled with the avant-gardists and the artists of French Impressionism. Later his work would take inspiration from the Fauvists and adopt a radical approach to colour.

Early years and influences

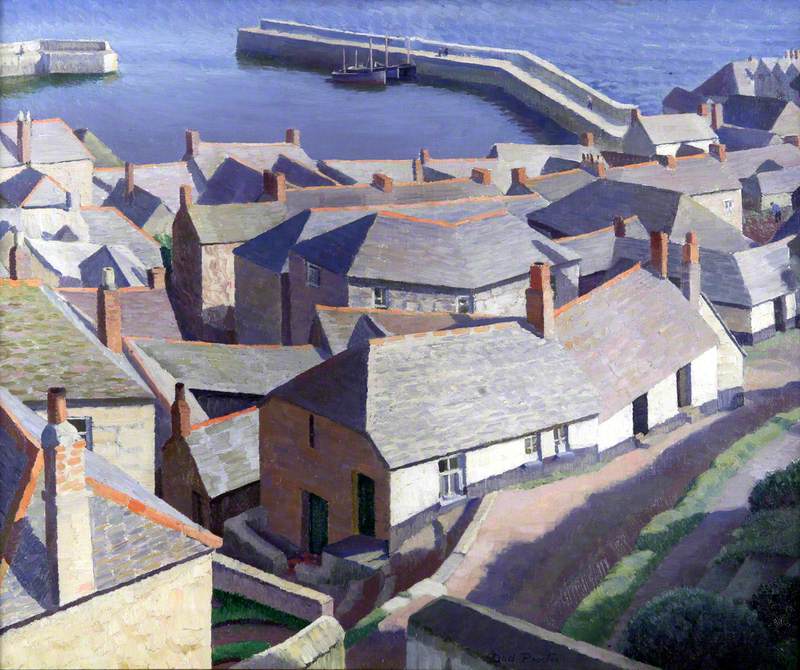

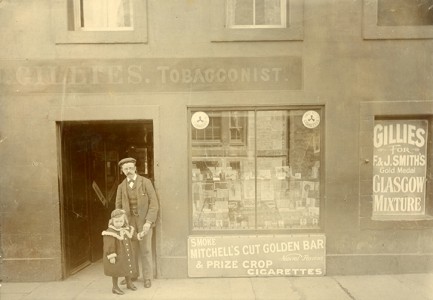

The oldest of four children, Fergusson was born and raised in Leith, then a small port town north of Edinburgh. Upon realising his vocation was painting, he abandoned his studies at Edinburgh University and enrolled at the Trustees Academy, an art school in the area. Unsatisfied by the teaching, he quit and taught himself. He set up his own studio in Picardy Place, Edinburgh.

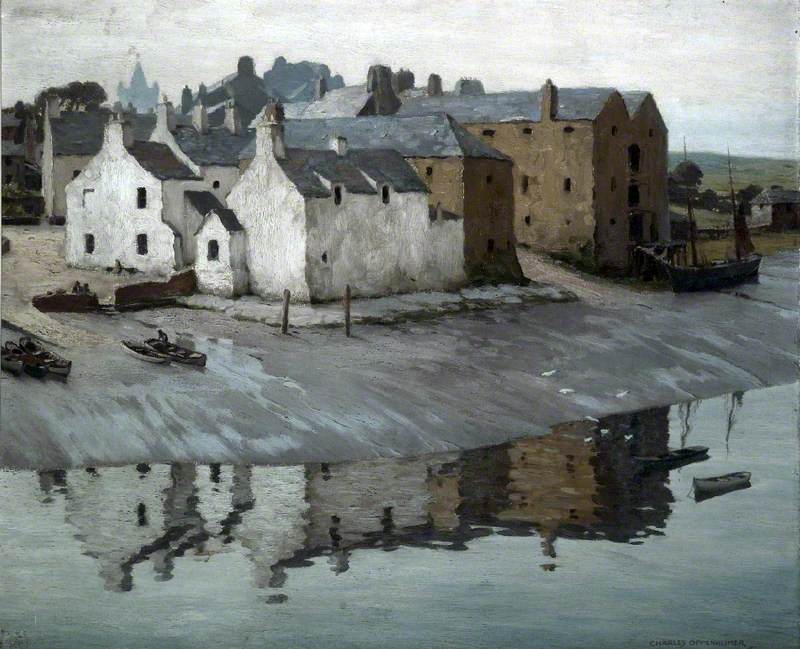

Taking his cue from the realism of 'The Glasgow Boys', a group of anti-establishment painters who were vehemently against the academic teaching of the arts, Fergusson decided to adopt their painterly style – impasto, thick brushstrokes and darker palettes. The group's leaders included artists such as James Guthrie, John Lavery and William York Macgregor, who took an interest in flattened Japanese prints, Celtic design and the emergence of Impressionism.

Morocco, Spain and France

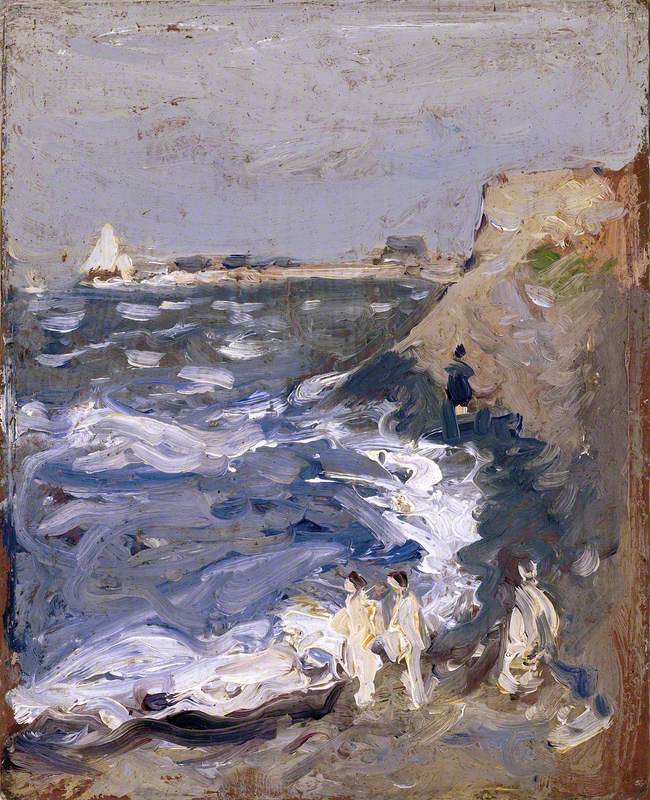

Shortly after, he voyaged overseas, visiting Morocco, Spain and eventually France, a country with which he had a lifelong obsession. A proud Scotsman who often spoke about the historic connection between France and Scotland, Fergusson insisted on writing 'Ecossais' after his name at exhibitions in Paris.

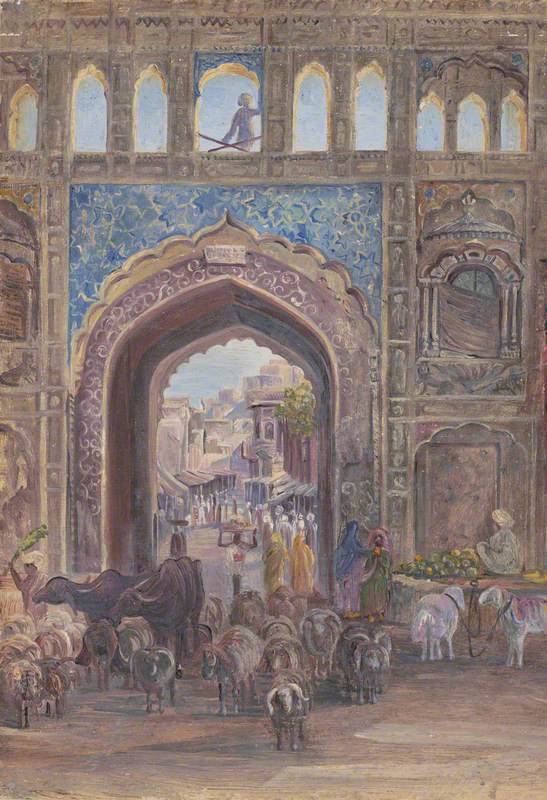

Fergusson first visited Morocco in 1899. By painting Tangier, he was following in the footsteps of the Glasgow artist Arthur Melville, who had painted a series of watercolours inspired by Tangier and other locations in North Africa and the Middle East.

Inspired by Melville, Fergusson once declared: 'Although I never met him or saw him, his paintings gave me my first start: his work opened up to me the road of freedom not merely in the use of paint, but freedom of outlook.'

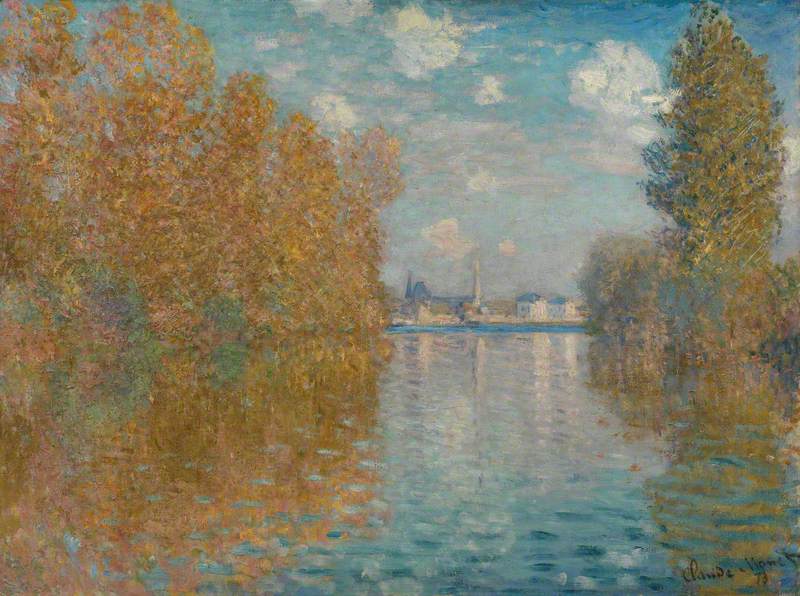

Throughout the early 1900s, Fergusson spent his time in Paris rubbing shoulders with the likes of Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. He continued to travel around France, often alongside Samuel John Peploe, who was to become a fellow Scottish Colourist.

In Paris, he studied the works in the Louvre and encountered the paintings of the Impressionists who, like the Glasgow Boys, preferred to paint realist subject matters 'en plein air' (i.e. outside). He took up his training at the Academie Julian and Academie Colarossi.

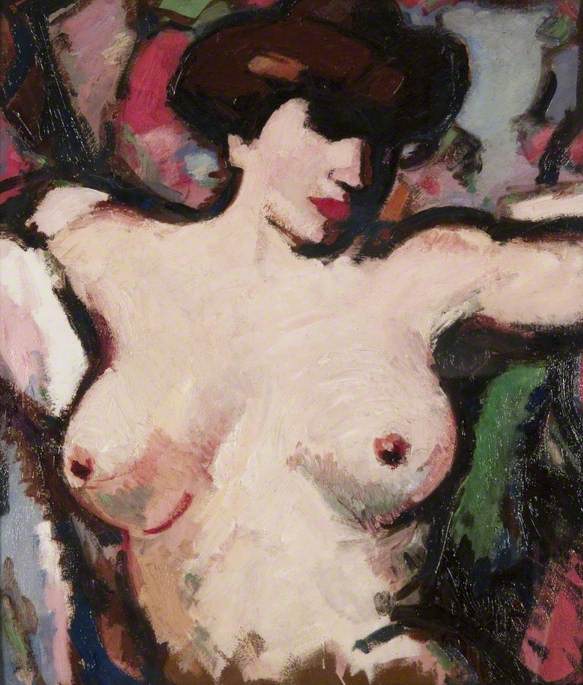

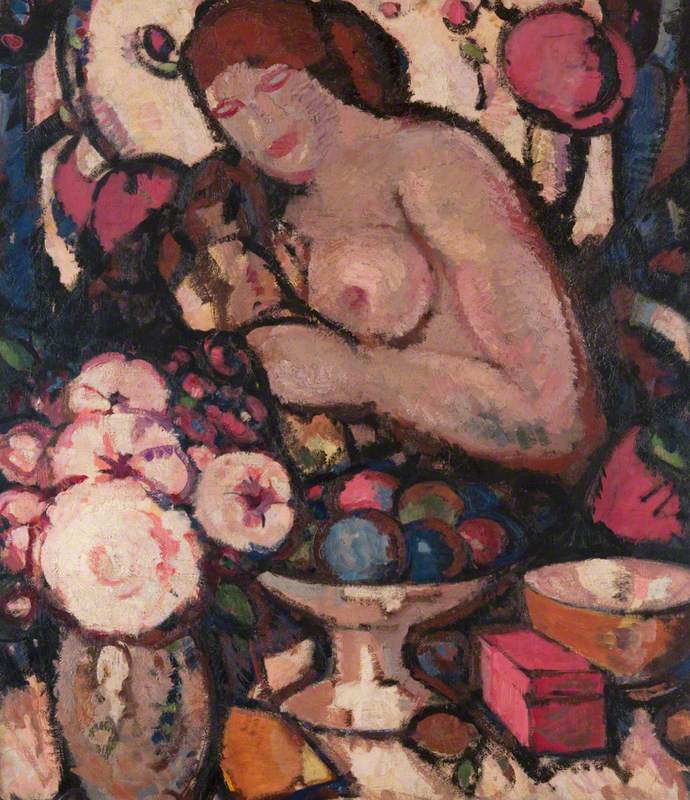

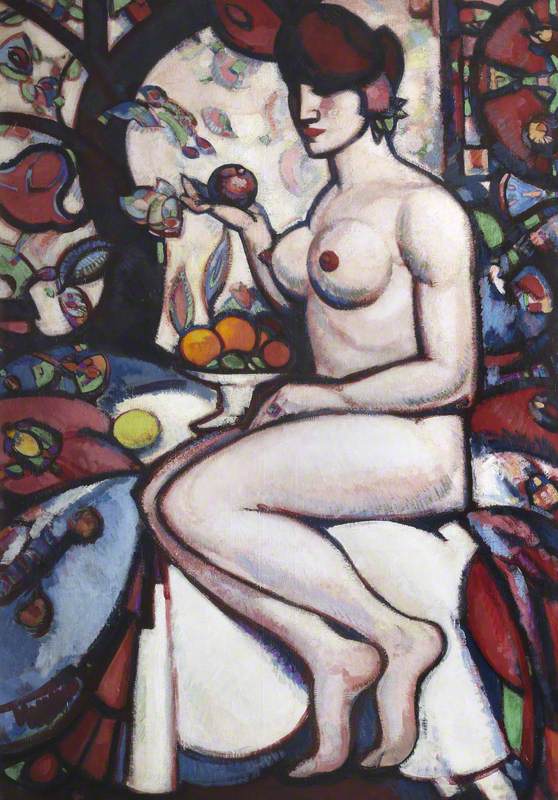

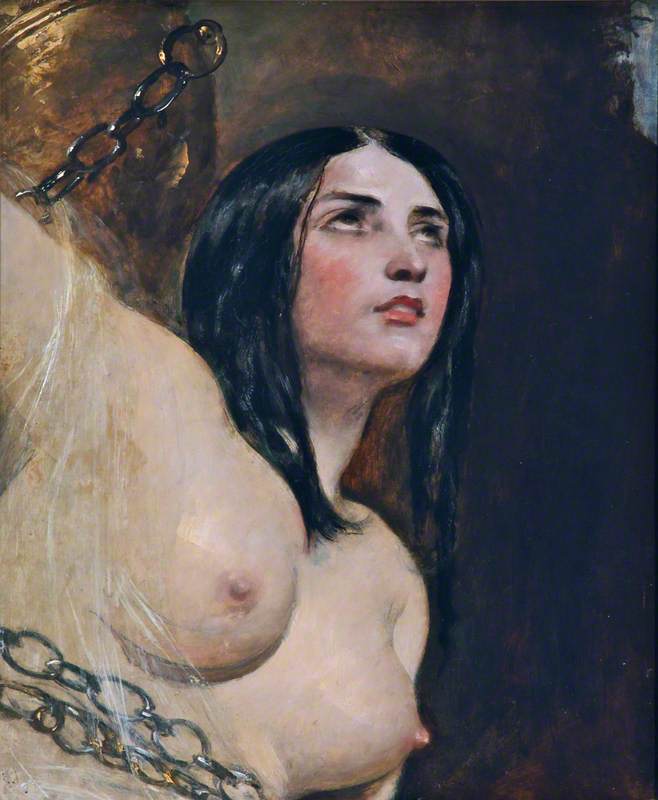

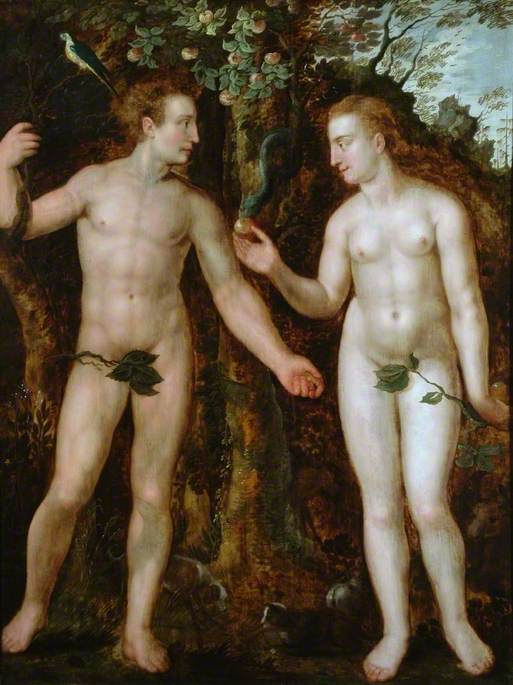

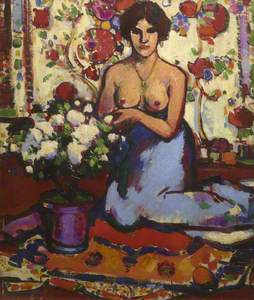

Fergusson's female nude from the early years of the 1900s bears strong resemblances to the nudes of Édouard Manet, especially in his use of impasto brushstrokes, a characteristic also attributed to the Glasgow School. He once remarked: '[Peploe and I] were very impressed with the Impressionists... Manet and Monet were painters who fixed our direction.'

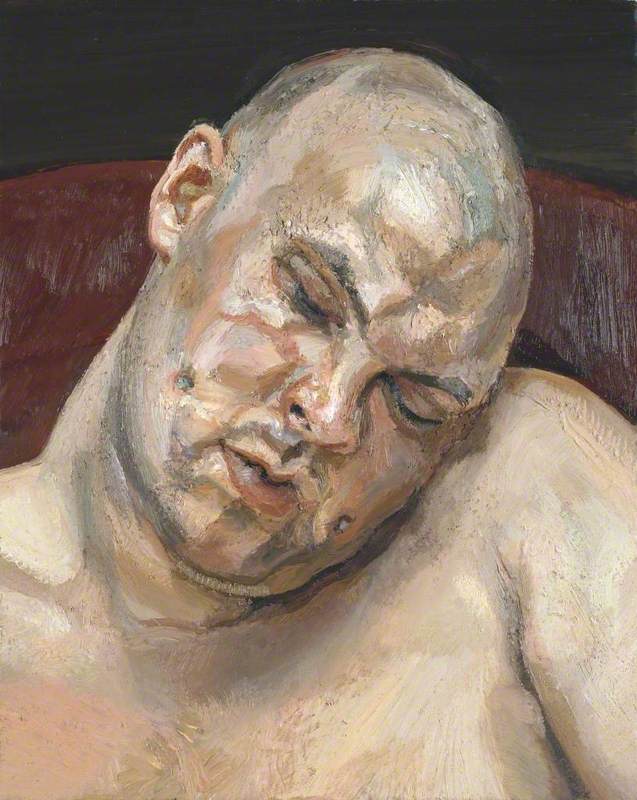

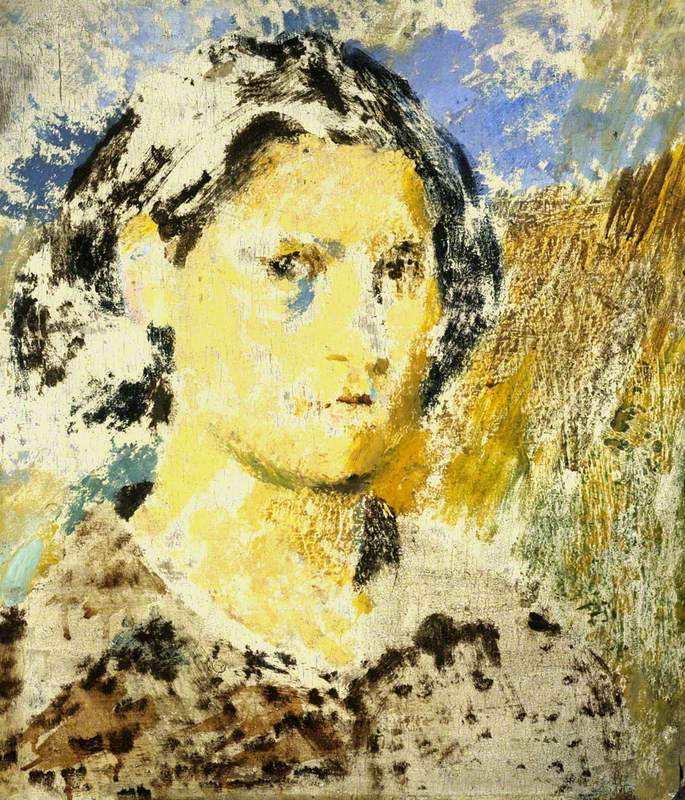

This painting is one of Fergusson's earliest self-portraits. Capturing himself smiling, the work conveys his lively character and charisma.

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961), Artist

c.1902

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

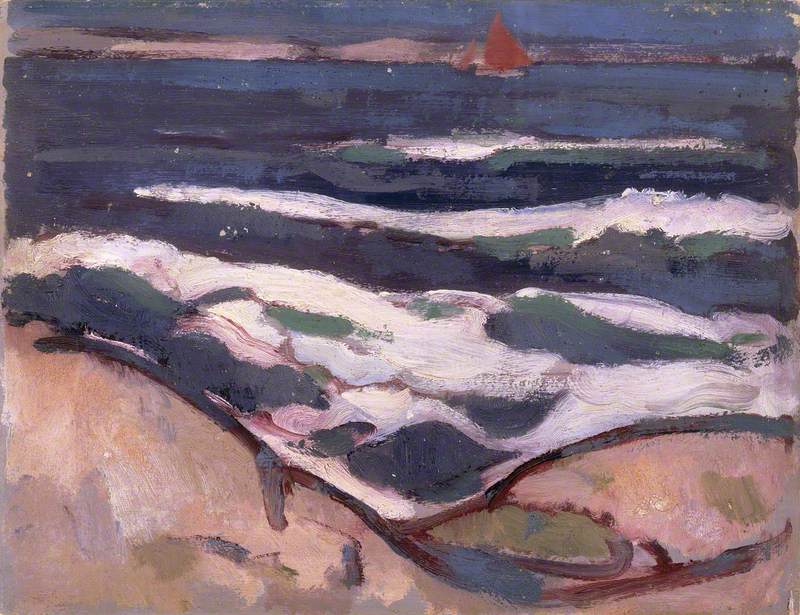

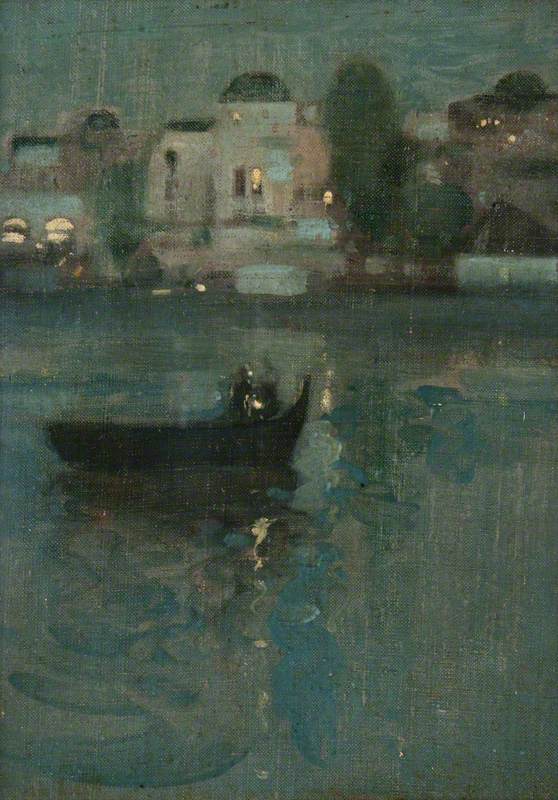

Around this time, Fergusson was also taking inspiration from the American artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who spent much of his career in both London and Paris.

El Grao, Valencia: Nocturne

1901

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

The painting Dieppe, 14 July 1905: Night was one of Fergusson's largest and most ambitious of the period. It perhaps pays tribute to Whistler's Firework Nocturne paintings.

Café society in Paris

In 1907, having succumbed to the creative, bohemian lifestyle abroad, Fergusson made the bold decision to move to Paris. He settled in Montparnasse, the artistic epicentre of the city.

He recalled: 'I was in Paris without any money or rich relations... but repeatedly encouraged by what some people call le bonair de Paris.' Warmly embraced by an intellectual crowd of artists and literary figures leading the avant-garde, Fergusson found a new home.

In the same year, he began creating paintings that emulated the works of the Impressionists, such as this 1907 painting titled Café-Concert des Ambassadeurs.

In Paris, he began sketching Anne Estelle Rice, a fellow artist who also became his lover.

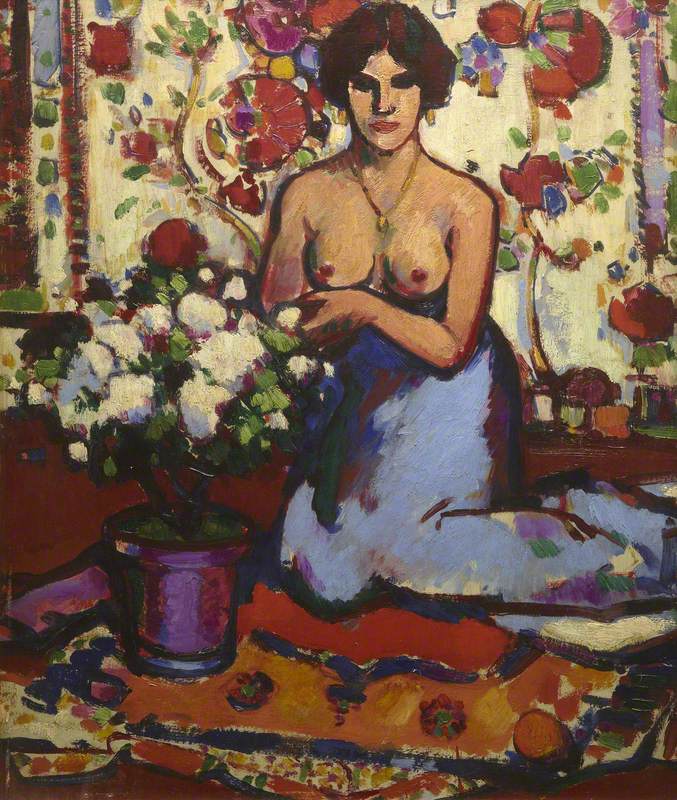

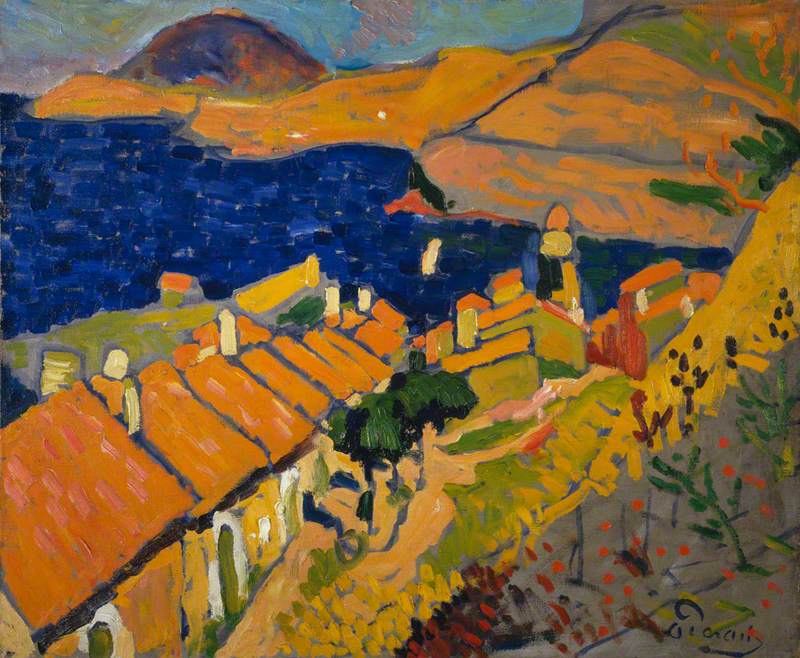

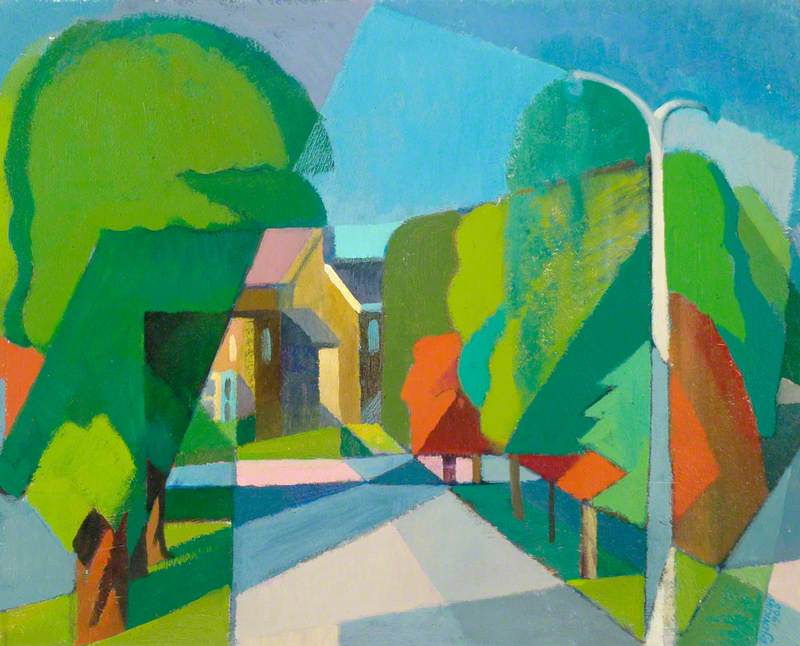

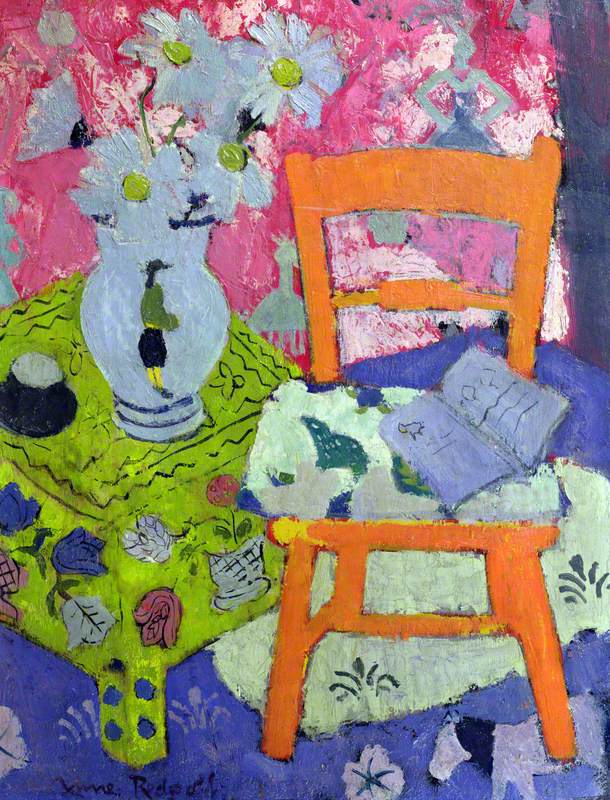

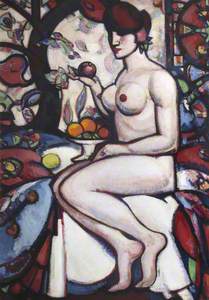

Around this time, Fergusson became enchanted with the movement titled the Fauves (wild beasts), avant-gardists who were proposing radically new approaches to colour, perspective and form. Central members included Henri Matisse, André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck whose unconventional works were displayed in the 1905 exhibition at the Salon d'Automne, which made a huge impact on Fergusson.

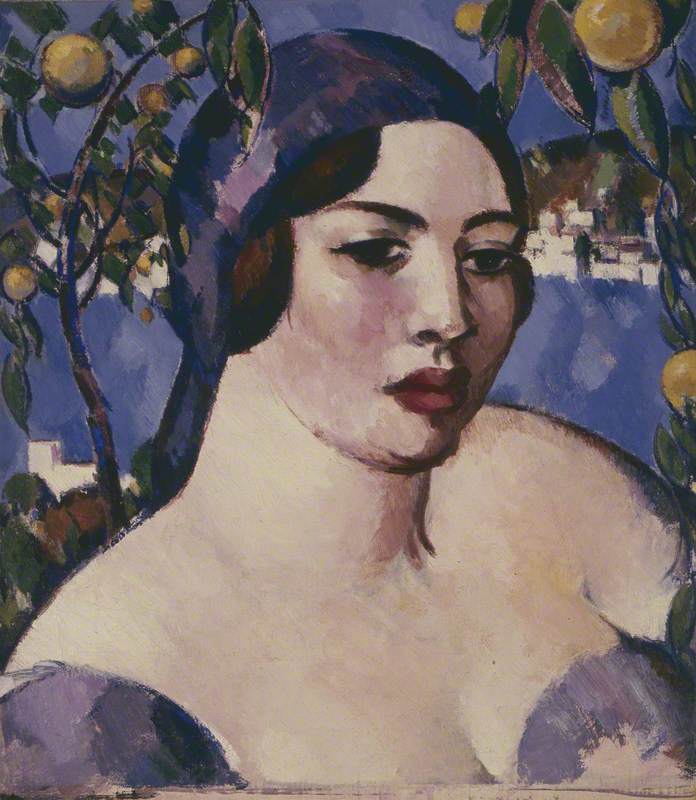

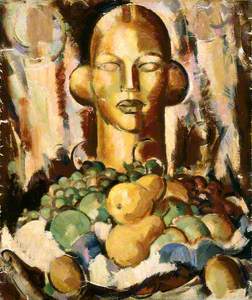

The female nude

Between 1910 and 1911, Fergusson became fixated with painting female nudes, mirroring the popular subject matter of the modern French artists.

By the turn of the century, artists had abandoned idealised representations of the female nude, and instead they adopted natural renderings.

Fergusson's nudes embraced a gritty realism, but also revealed his experimentations with colour.

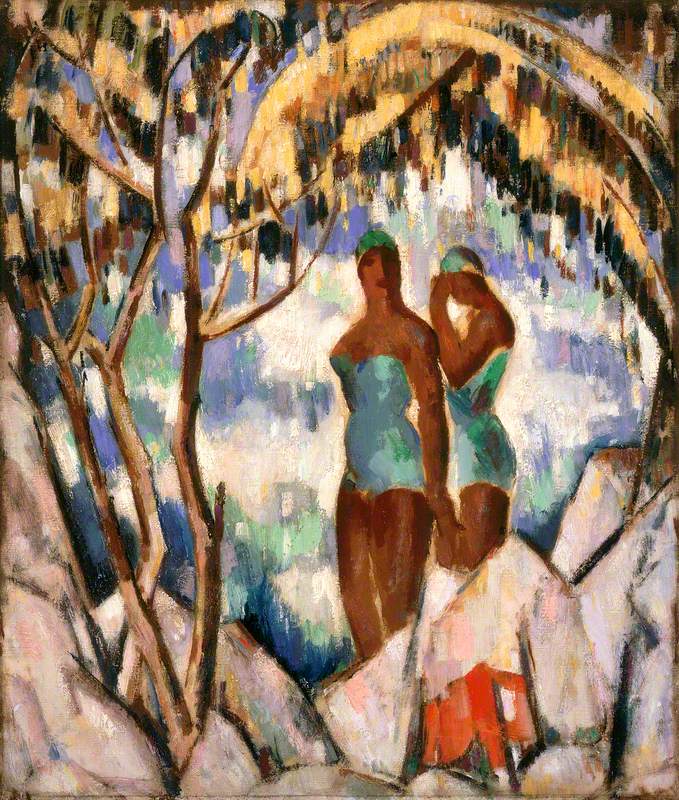

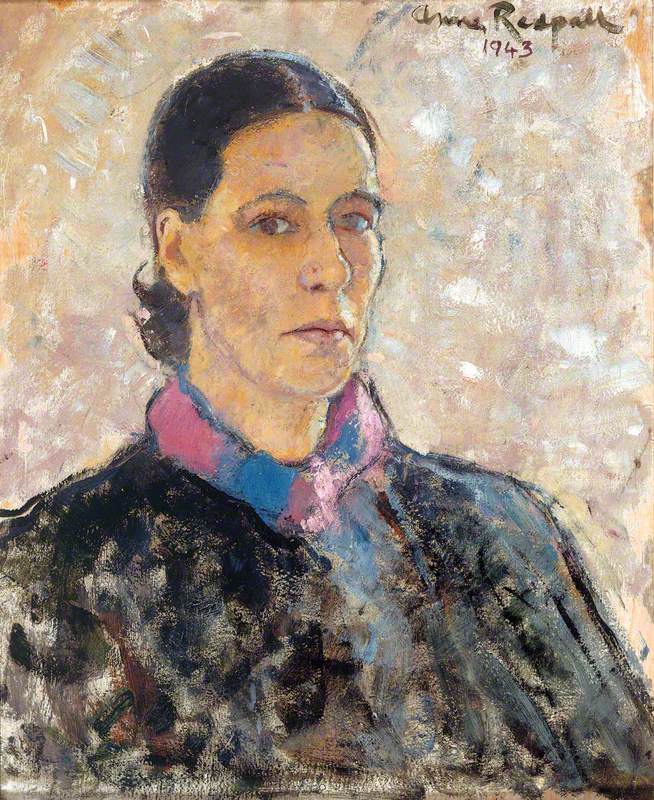

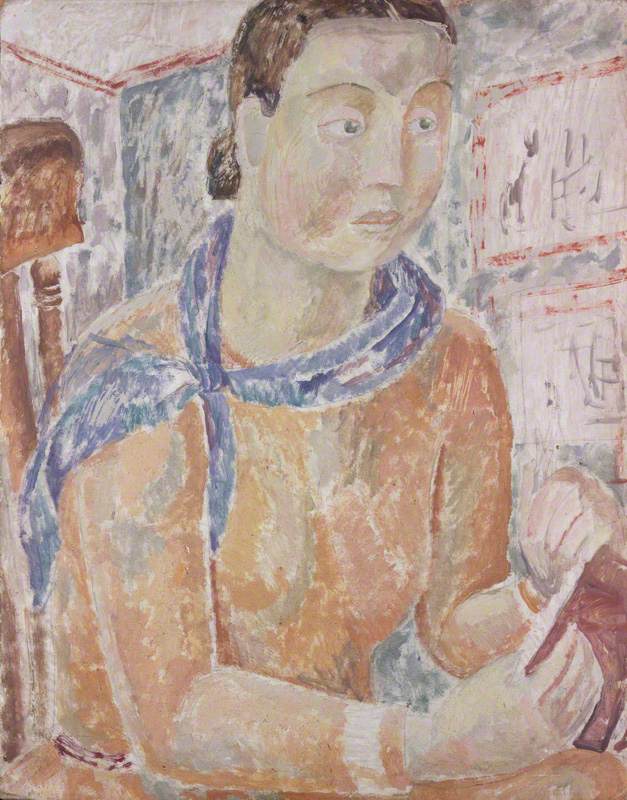

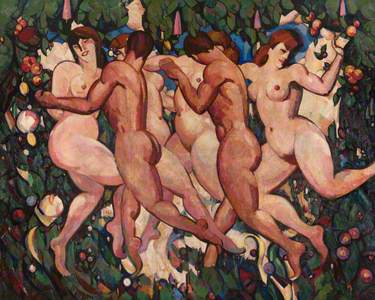

In 1913, he met the pioneering English dancer Margaret Morris while she was touring with her own dance company in Paris. They began a personal and professional relationship that would last until the artist's death (though allegedly Fergusson allowed her to have other relationships). Morris established a dance school in England and became a proponent of the celebrated dancer Isadora Duncan. She also experimented with painting – 33 of her works are on Art UK.

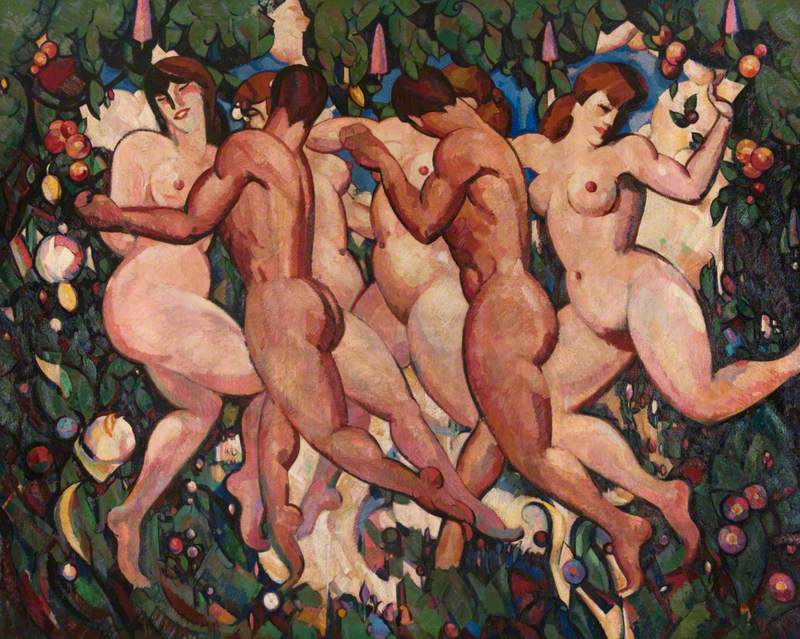

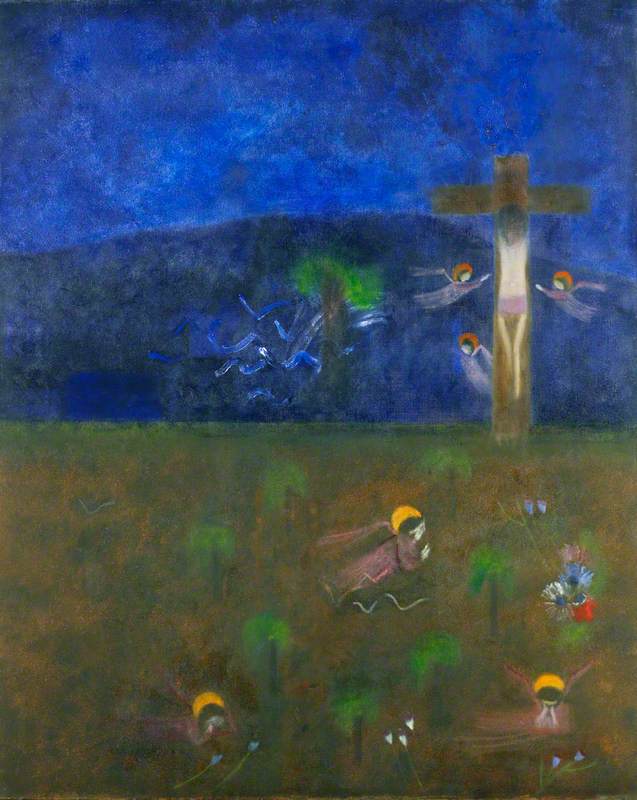

Around this time, perhaps inspired by Morris, Fergusson's work began to explore the theme of dance as a subject matter. Perhaps the most famous example is Les Eus (1910), which was possibly also influenced by Matisse's The Dance – a painting that had been exhibited at the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1910. An energetic painting imbued with expressive sexuality, both it and the Matisse were later read in connection to Stravinksy's The Rite of Spring, which was first performed in Paris in 1913.

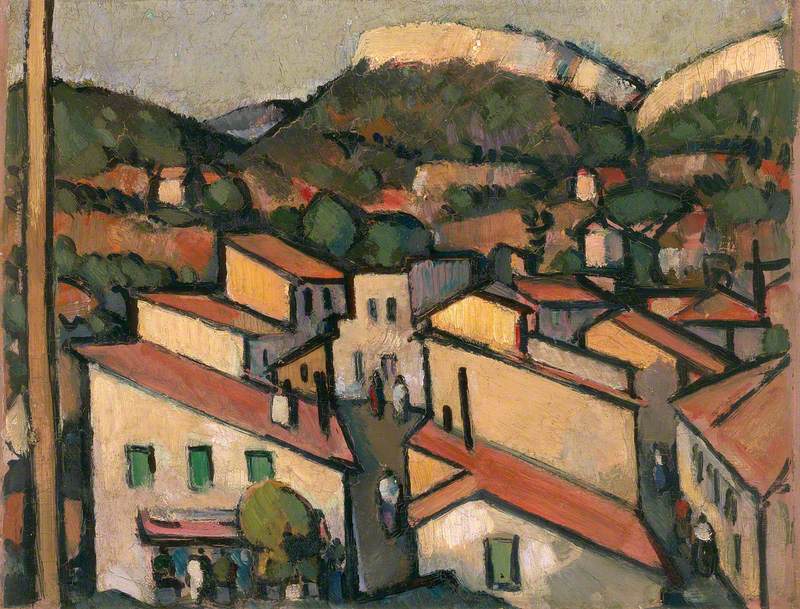

Outbreak of war and a shift in practice

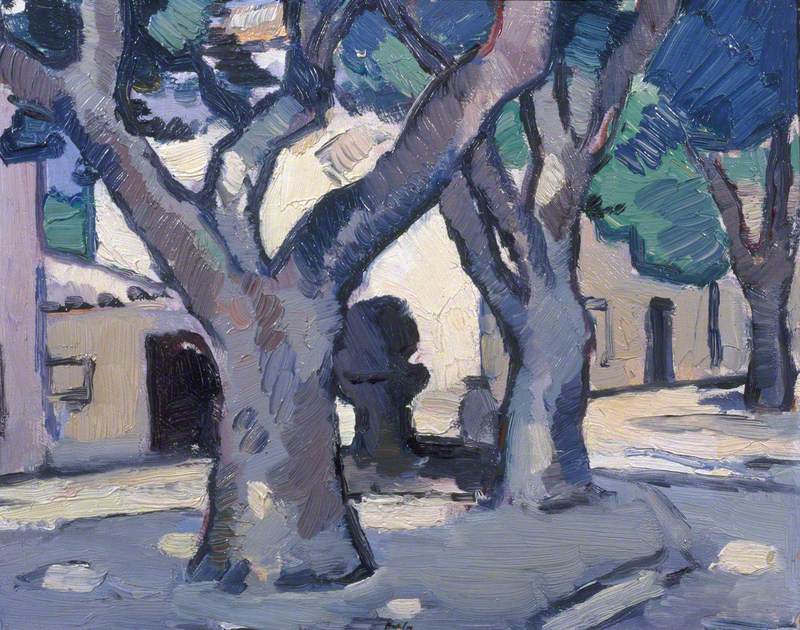

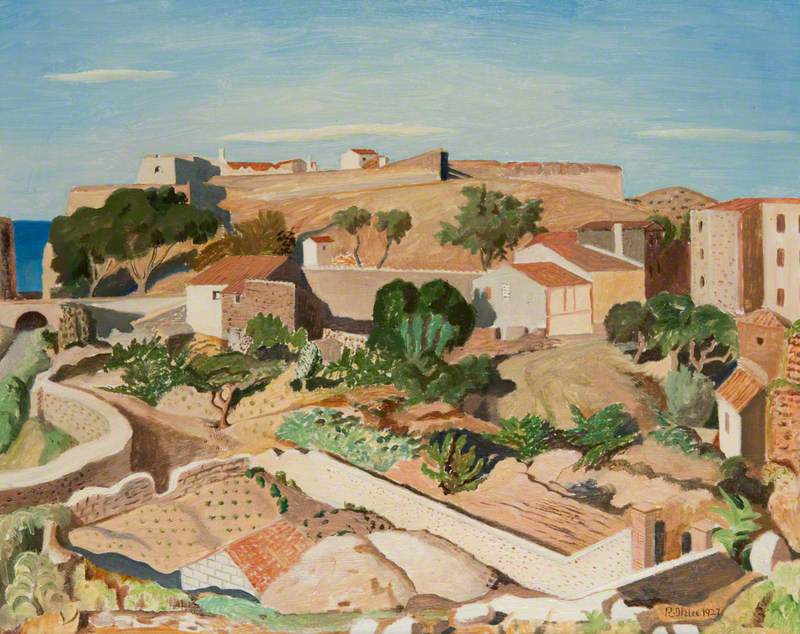

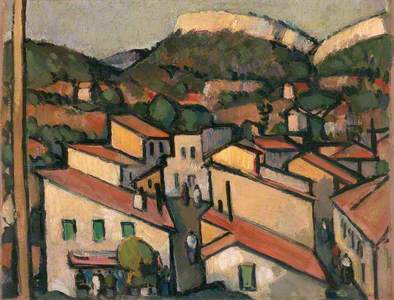

Despite his sparkling social life in Paris, Fergusson declared his fatigue with the city in 1913: 'I had grown tired of the north of France; I wanted more sun, more colour; I wanted to go south.' For the rest of his life, he would regularly escape to regions in the south, chasing the warm, Mediterranean climate.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Fergusson returned to England with Morris and successfully avoided being conscripted into the army. Now in his 40s, he was at the forefront of European modernist art and had no intentions of sacrificing his life.

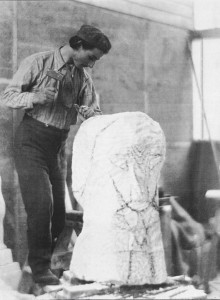

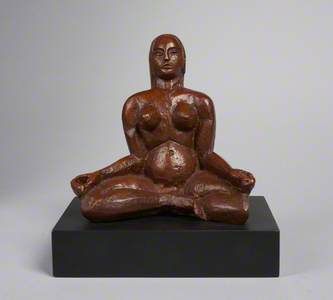

In August 1916, Fergusson referred to this sculptural carving above in a letter he sent to Margaret Morris: 'I've been at it two afternoons and have done three sides of a stone, nearly square. It resembles somewhat the one you've seen. Same kind of stone...'

This small figurine corresponds to and reflects the 'exotic' and 'oriental' themes explored by both Morris and Fergusson.

Female Dancer

(nude, legs flexed, arms behind head)

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

So how did Fergusson avoid being conscripted into the army? At the start of the First World War, the British army's age limit was raised to 51 meaning Fergusson was eligible for active service.

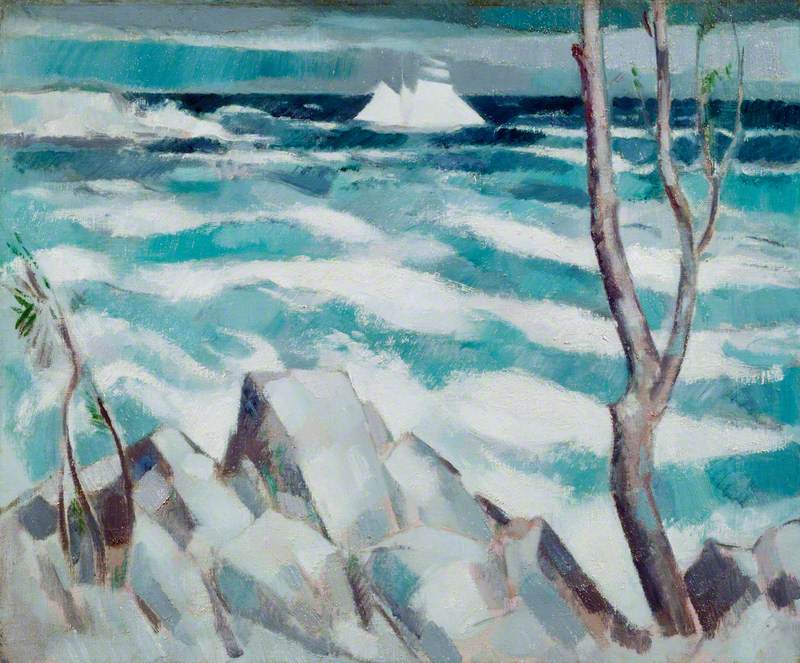

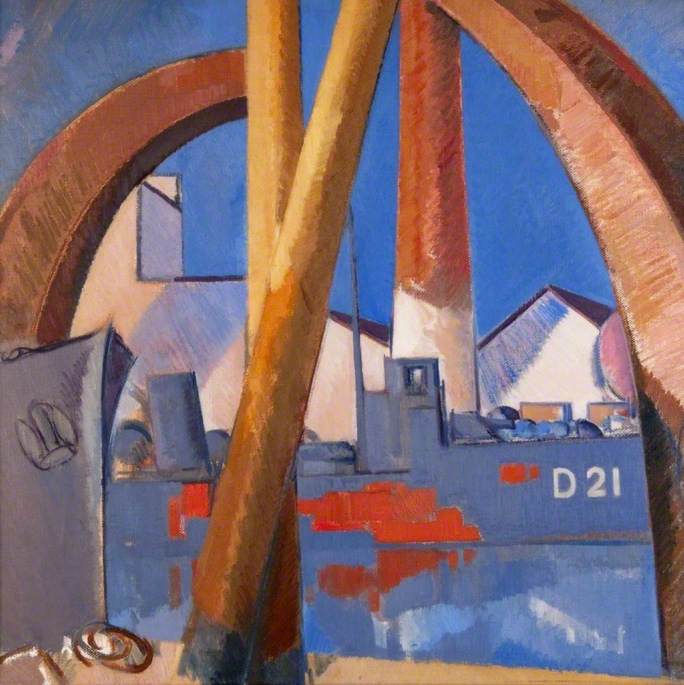

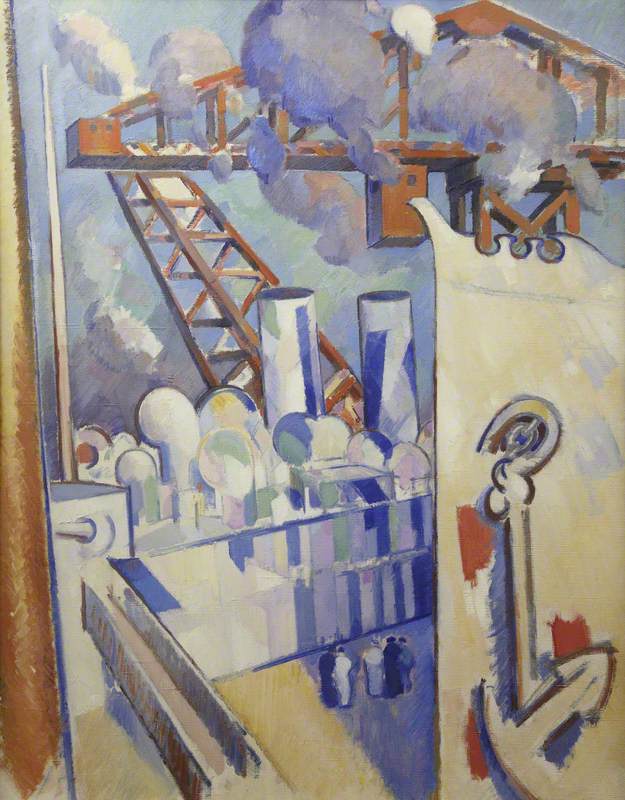

He wrote to Alfred Yockney, the secretary of the British War Memorials Committee at the Ministry of Information, proposing that a committee of artists be formed to decide how best to make use of their abilities during the war. Yockney agreed to recruit Fergusson as an artist for the Ministry of Information. Despite not technically being a 'war artist', he was permitted to go to the Portsmouth docks to paint what he saw. There, he created these works of the dockyard.

By the time he had submitted his paintings for consideration by the Admiralty, the war had already finished and his paintings were returned. It was only 14 years after the artist's death that one of his paintings was purchased by the Imperial War Museum.

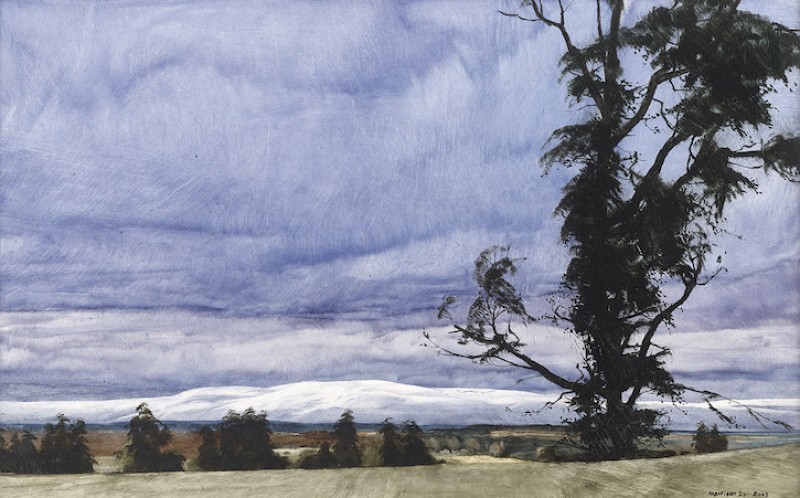

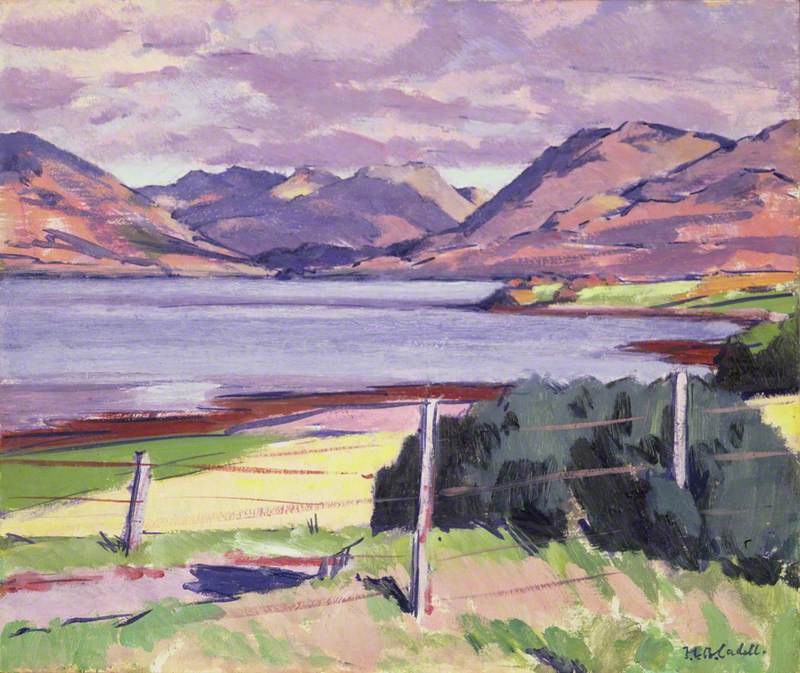

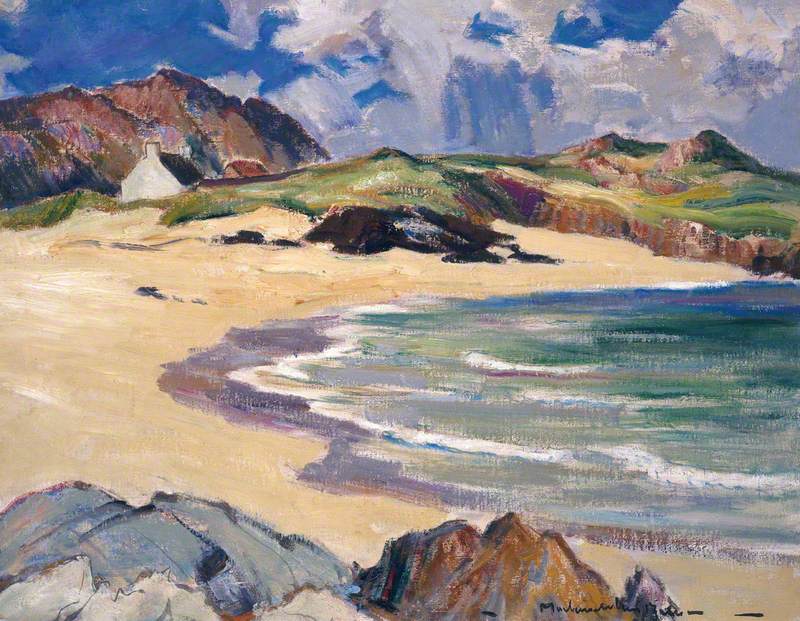

The inter-war years

In the 1920s, Fergusson settled in a studio in London and held his first solo exhibition in 1923. He produced a series of Scottish landscapes but spent most of his time in London where Morris's dance company was rising to success. The couple worked together and Fergusson became Art Director of her Margaret Morris Movement (MMM) schools, designing costumes for her stage productions.

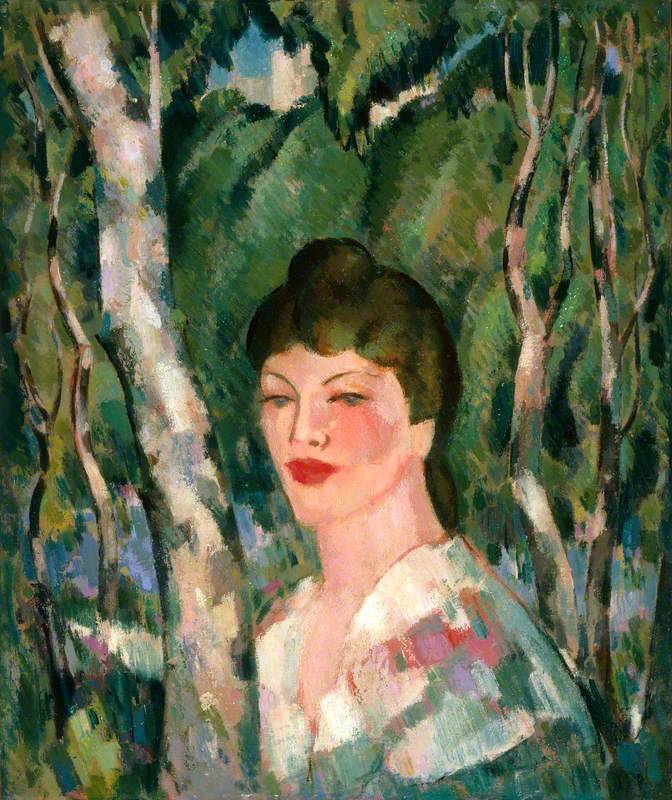

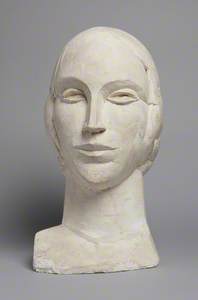

Thorenc Head (Margaret Morris, 1891–1980)

1929

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

In 1928, Fergusson and Morris returned to Paris, where they were reunited with the artistic community they had mixed with before the war. By this time, Fergusson was a central member of the group that had become known as the Scottish Colourists.

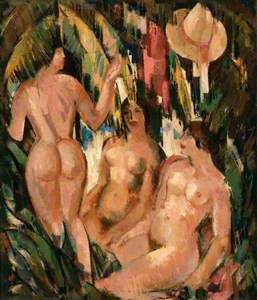

Spring in the South (Margaret Morris, 1891–1980)

1934

John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961)

At the start of the Second World War in 1939, Fergusson and Morris returned to Britain and settled in Glasgow. There, Fergusson became a member of the Glasgow Art Club and Morris established the Celtic Ballet. The couple collaborated on many creative projects together, including setting up the New Art Club.

During this time, Fergusson created more sculpture – an art form he dabbled with throughout his career.

Later years

Fergusson and Morris remained in Glasgow after the war, but frequently returned to France in the summer. Towards the end of his life, Fergusson appeared to focus on paintings that reflected the Mediterranean summer heat and, of course, his fascination with the female form.

One of the last survivors of the avant-garde era led by the Impressionists in Paris, Fergusson died aged 86 in 1961. After his death, Margaret Morris, with whom he had spent fifty years, created the J. D. Fergusson Art Foundation which still owns the majority of his works today.

In 1992, the collection opened the Fergusson Gallery in Perth, part of Culture Perth and Kinross, a museum and gallery commemorating his life and work. The gallery also holds a number of pictures by Morris.

Today, Fergusson is remembered not only as one of the talented group of Scottish Colourists, but also as a pioneer of modern painting who absorbed many strands and currents of the European avant-garde.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK