One warm evening in 1944, a group of Welsh miners crossed a bridge on their way home from work and changed an artist’s life forever.

The sun was low, and cast a glowing orange light across the scene. Probably the men didn’t notice Josef Herman watching: if they did spot him, they might have wondered how a young Polish émigré painter had found himself in the small town of Ystradgynlais. But to Herman it was the miners, not he, who were the noteworthy sight:

'For a split second their heads appeared against the full body of the sun, as against a yellow disc – the whole image was not unlike that of an icon depicting the saints with their haloes... The magnificence of the scene overwhelmed me.'

Herman had arrived that day, on a visit from London that he expected to last a fortnight. He stayed 11 years, and became a respected chronicler of the Welsh mining communities of post-war Britain. How did he get there?

Herman was aware of these contemporary troubles, but saw something else in Ystradgynlais, too: an enduring, close-knit community and a ‘monumental’ way of life that he respected and wanted to honour.

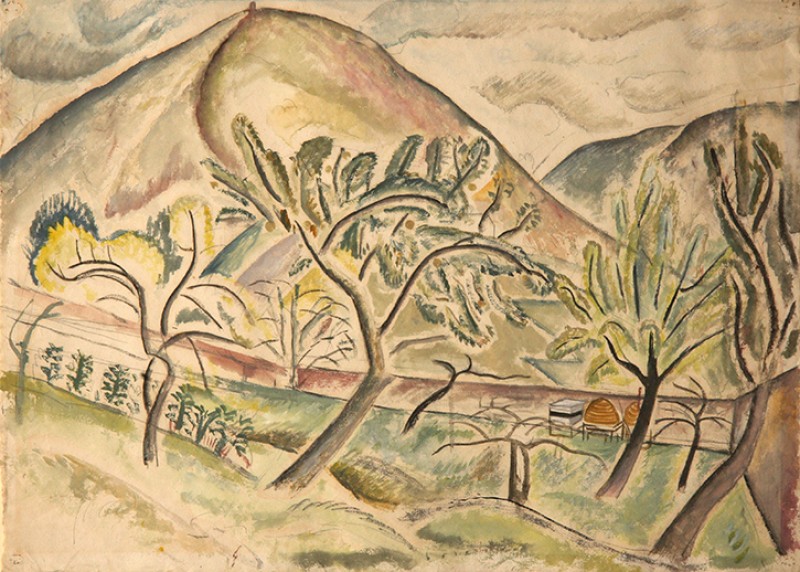

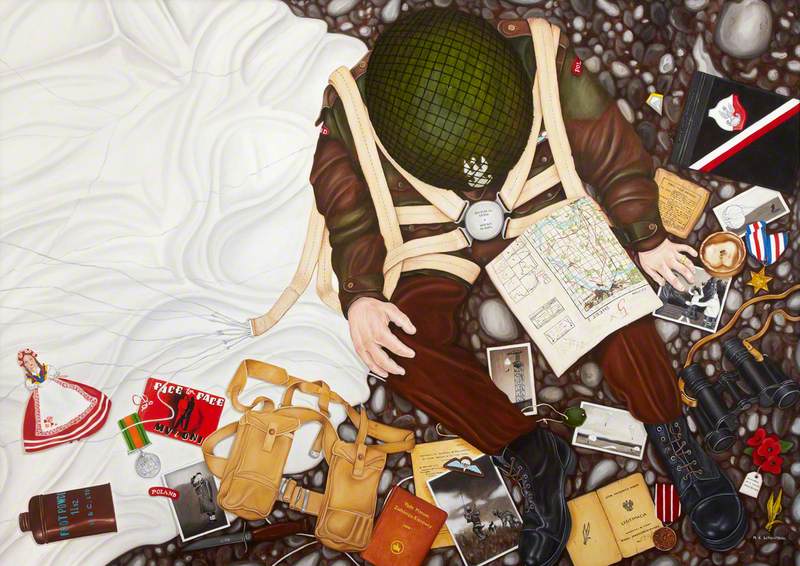

The artist’s journey to Ystradgynlais had been a troubled one. Born to working-class Jewish parents in Warsaw, he trained as a typesetter and graphic designer but later turned to painting. As a young man he was left-wing, idealistic, and committed to depicting the experiences of Poland’s poor. His earliest sketches were of workers in city ghettoes and peasants in the Carpathian Mountains, and he found much of modern painting, particularly abstraction, frivolous. In 1938, amid growing anti-Semitism and the threat of war, he moved alone to Brussels. He would never see his family again. In 1940 he was displaced to Glasgow, fleeing the German advance. It was there, two years later, that he discovered his parents and other relatives had been murdered by the Nazis.

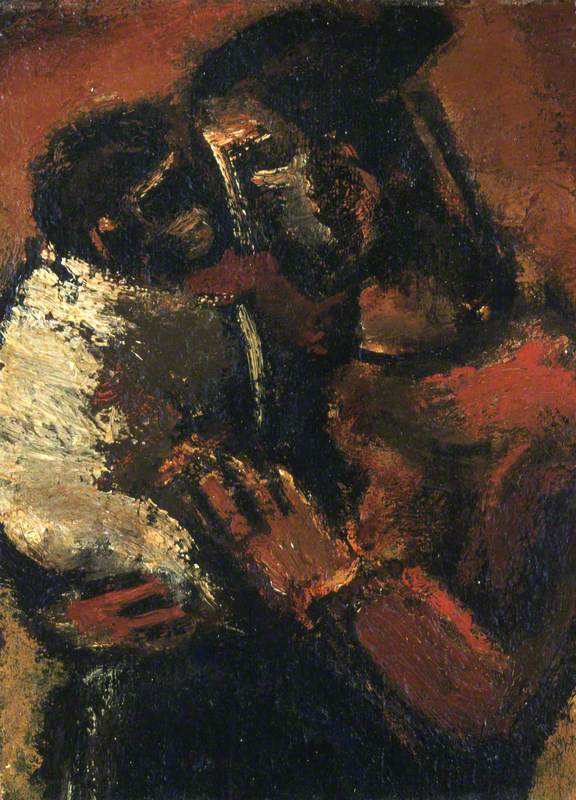

Herman channelled his grief into his work, creating vivid ‘memory paintings’ that evoked his childhood and Jewish heritage, along with compositions addressing the horrors of the pogroms. In 1943 he moved again, to London, but by now he felt emotionally and artistically spent. ‘The nostalgia for my childhood years had burnt itself out and nothing had taken its place,’ he later recalled, ‘except a vague feeling for big forms and a cry within me for a new belief in man’s serenity.’ One painting from this period, in the Ingram Collection, sums up the artist’s struggle. It depicts a woman and child sat side by side: they lean on each other, their heads downturned in an expression of both intimacy and sadness. It is at once a poignant image of a man yearning for his dead mother; a lament for the plight of millions of refugees; and a symbol of timeless familial love. Herman created it in 1943, and scribbled across the top-right corner of the page: Where to now? The following year, he had his own surprising answer: Ystradgynlais.

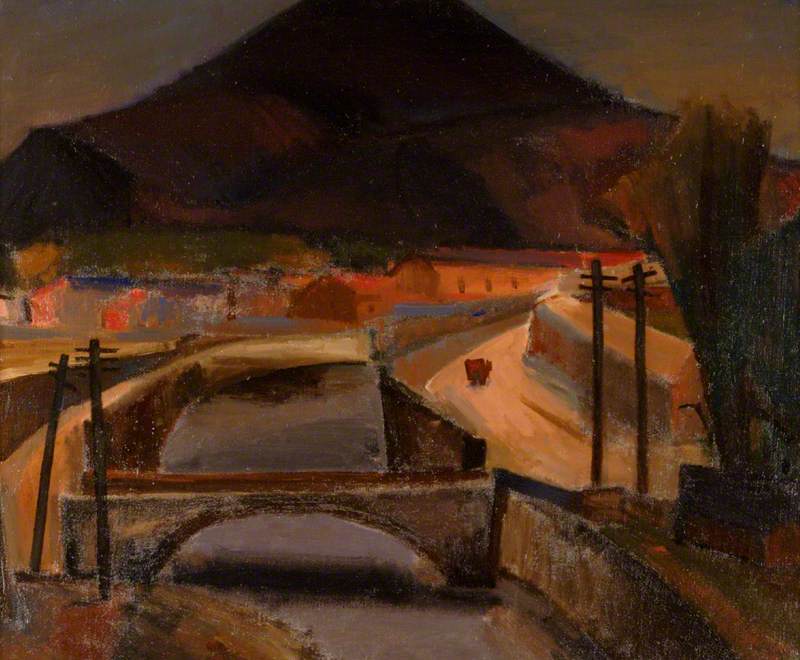

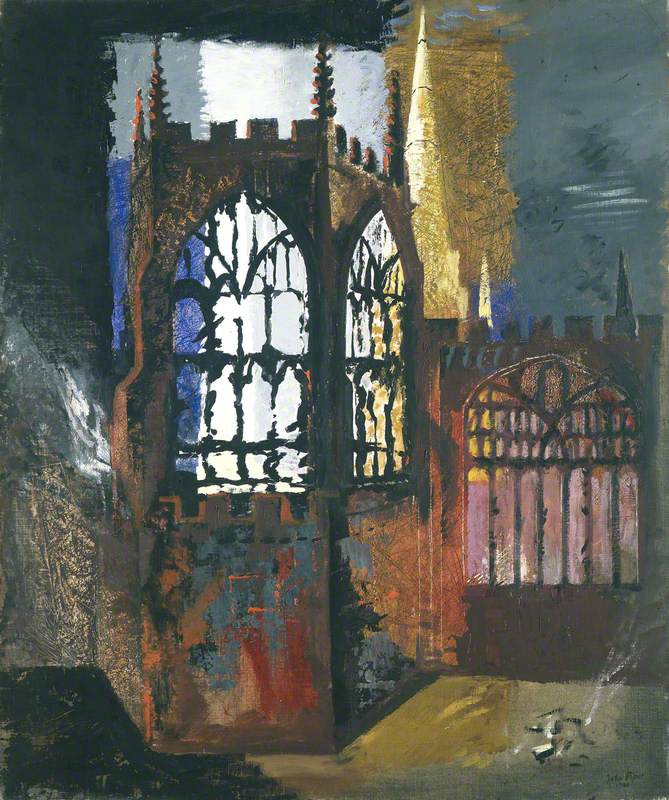

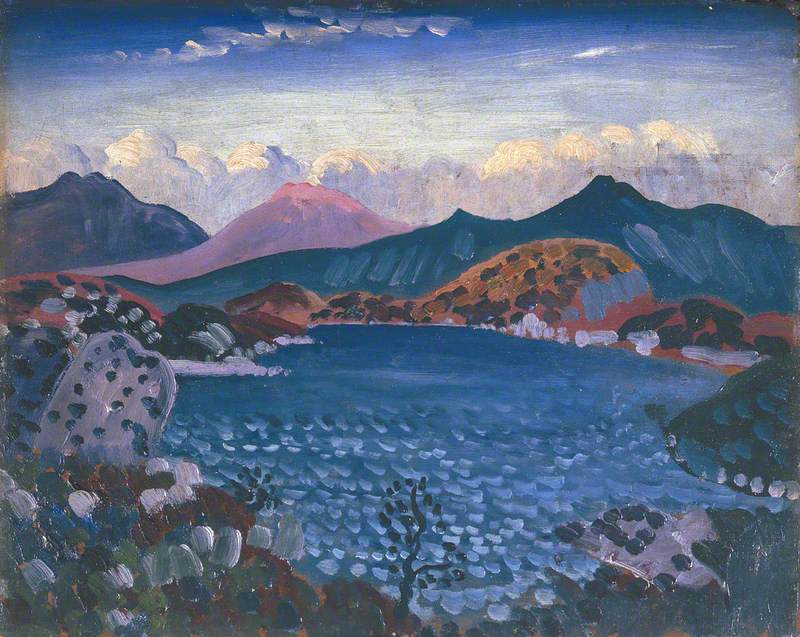

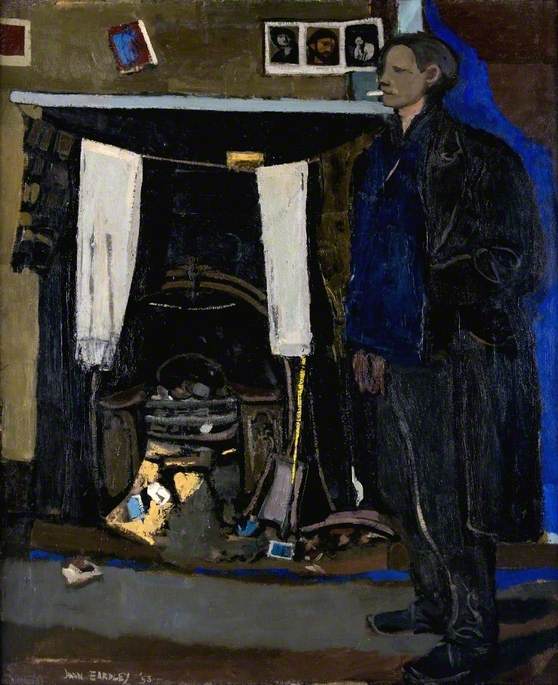

Herman visited South Wales at the suggestion of a friend, and meant to continue to Scotland to paint fishermen in Skye. Perhaps he already had a sense that, to find the ‘big forms’ and eternal subjects that he longed to paint, he would have to leave bustling London. But Ystradgynlais was a revelation. It was not a picturesque town: Herman’s paintings, such as The Bridge, Ystradgynlais of 1946 (now in the Southampton City Art Gallery) record its low-terraced cottages, wonky telegraph poles, towering coal tip, and the looming profile of the nearby Craig-y-Farteg mountain. But the artist had no time for romantic vistas – he was interested in the landscape only insofar as it supported people.

Coal mining had been the dominant industry in South Wales since the 1850s, and in the 1940s the majority of Ystradgynlais men still worked the coalface. But it was a hard and dangerous profession, and as the industry struggled in the twentieth century, strikes and disputes were common. The year Herman arrived, in 1944, the National Union of Mineworkers was formed in anticipation of the sector’s nationalisation. Herman was aware of these contemporary troubles, but saw something else in Ystradgynlais, too: an enduring, close-knit community and a ‘monumental’ way of life that he respected and wanted to honour. Mining, like fishing and farming, was an ancient occupation – people have worked the land for tin, copper and coal for millennia – and Herman, after years of displacement, was looking for somewhere with roots. ‘I have probably chosen to paint miners, rather than factory workers’, he once explained, ‘because miners, like peasants, have this deep attachment to their work and its surroundings.’

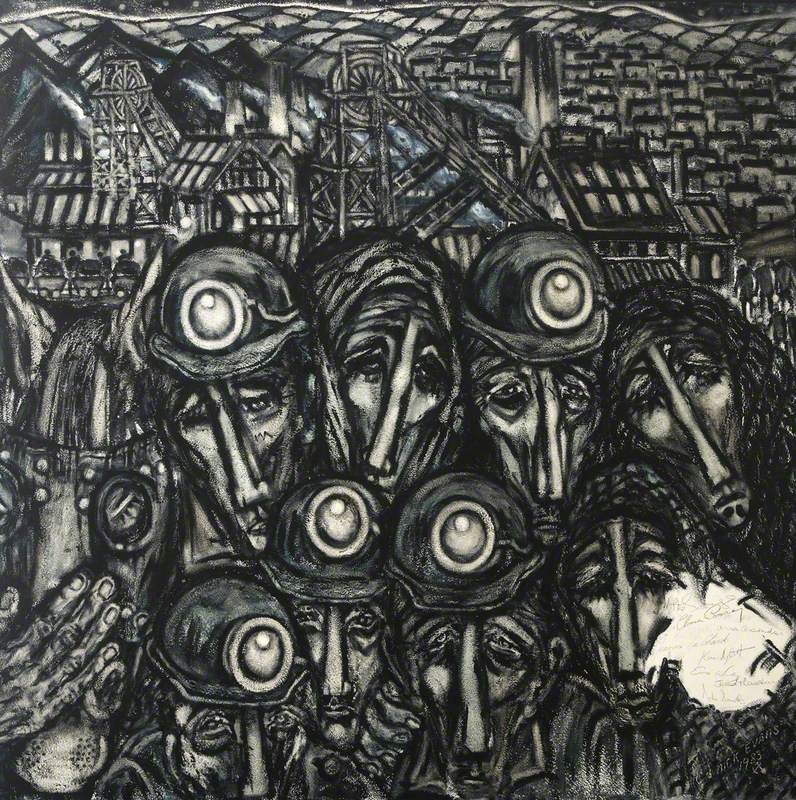

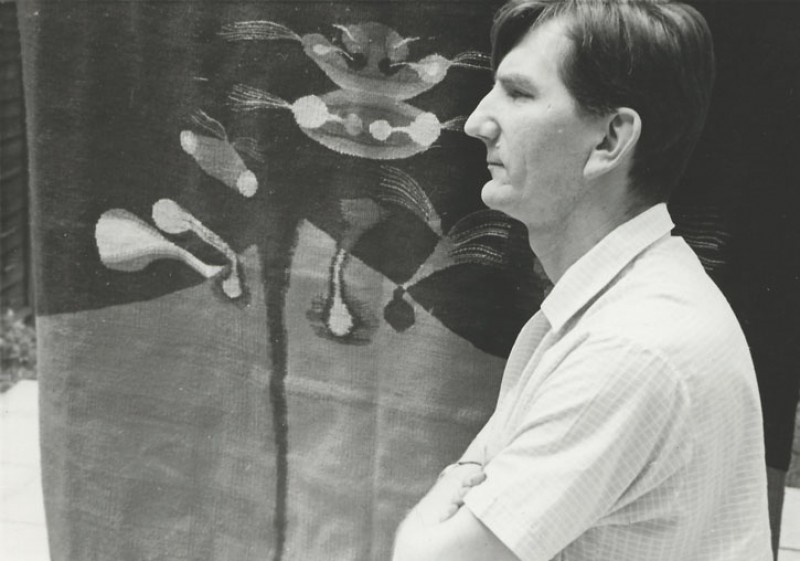

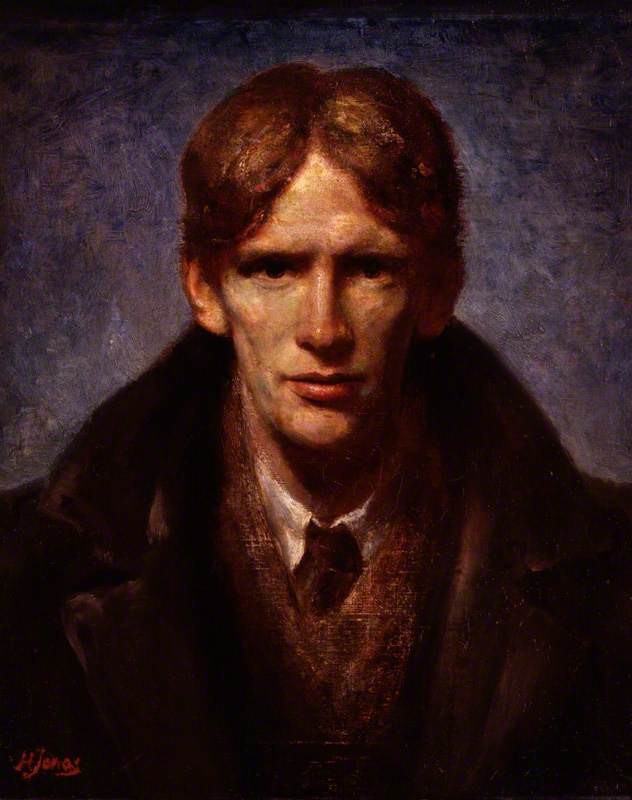

For the first few months that he lived in Ystradgynlais Herman didn’t paint at all. Instead, he drew: he went down into the mines to sketch, and recorded everyday life in the town, getting to know the locals as he did so; they came to refer to their new neighbour as Joe Bach, and later Herman painted several of their portraits. There was already a strong tradition of documentary art in South Wales, as Welsh miner-painters such as Vincent Evans and Evan Walters recorded their experiences. Herman wanted to create something different. ‘It was clear to me that multiplying scenes from the miners’ lives, or varied aspects of demographical landscapes will get me nowhere,’ he decided; ‘what I was out for was a deeper synthesis to concentrate ideas, to distil feeling into form.’

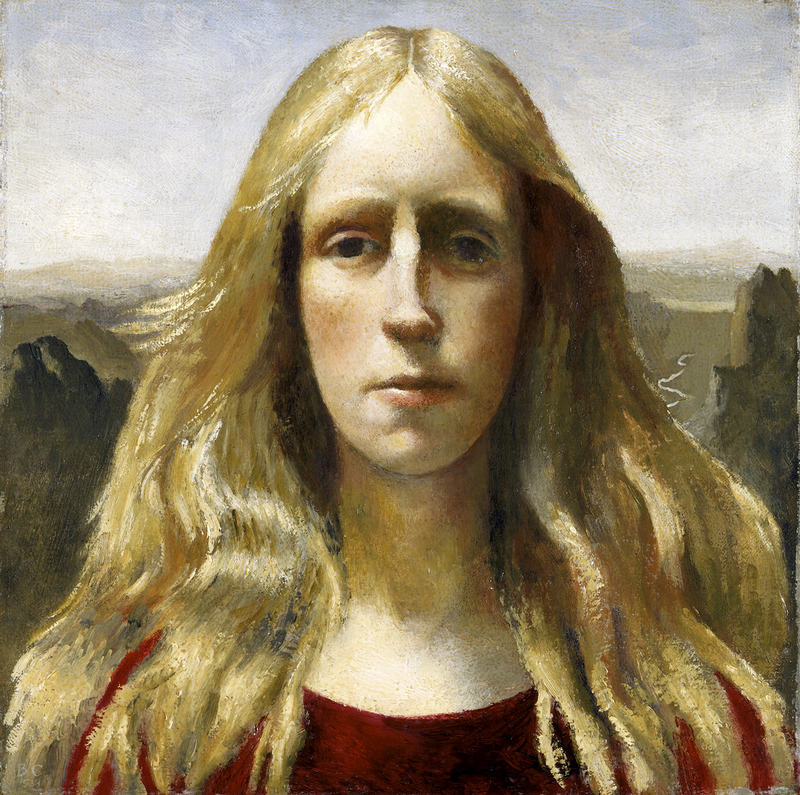

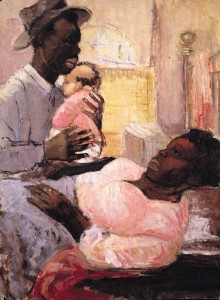

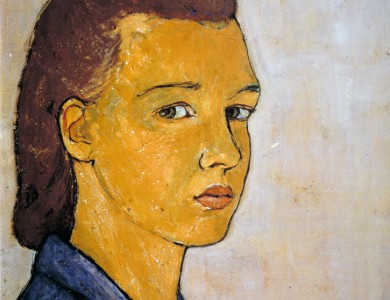

Over time, he developed powerful ways of achieving this. One was his distinctive way of depicting the miners: heavy-set, with broad shoulders and huge, powerful hands, they look as though they have been carved out of the mountains themselves. The women in Herman’s paintings are also monumental. In Ystradgynlais he tended to paint them in maternal roles, although at other stages in his career he depicted women at work. Herman monumentalised his figures to convey their inner and outer strength. Images such as Mother and Child at the National Library of Wales, and Miners at the Southampton City Art Gallery, are as much icons to labour as they are paintings of real people.

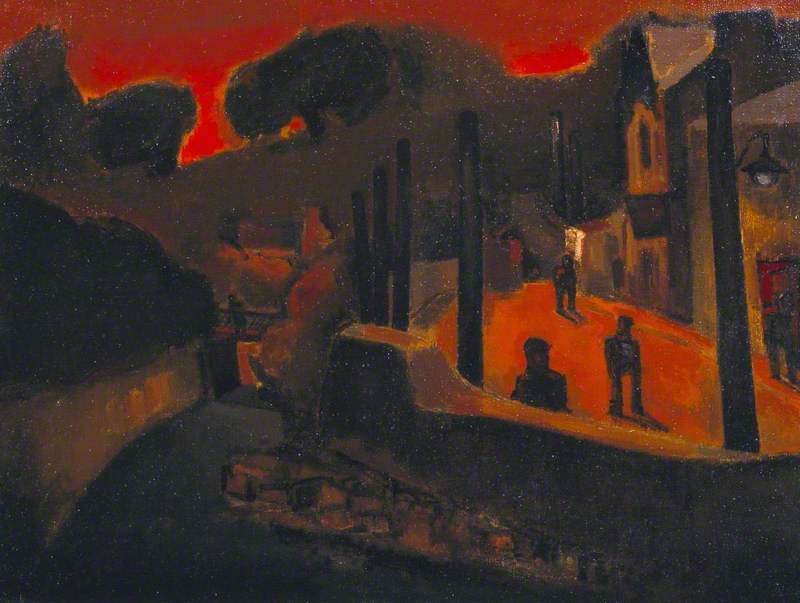

Herman added to this spiritual feeling through his use of colour. Evening, Ystradgynlais recalls the mystical sunset that he witnessed on his first day in town. Signs of modernity remain – such as the street lamp on the right – but everything is bathed in an otherworldly orange light, and the figures stand transfixed. ‘Endurance and silence are as frequently in my landscapes as in my figure paintings,’ he acknowledged. ‘I do not need a war to make me think of heroism. It is our endurance of the everyday.’

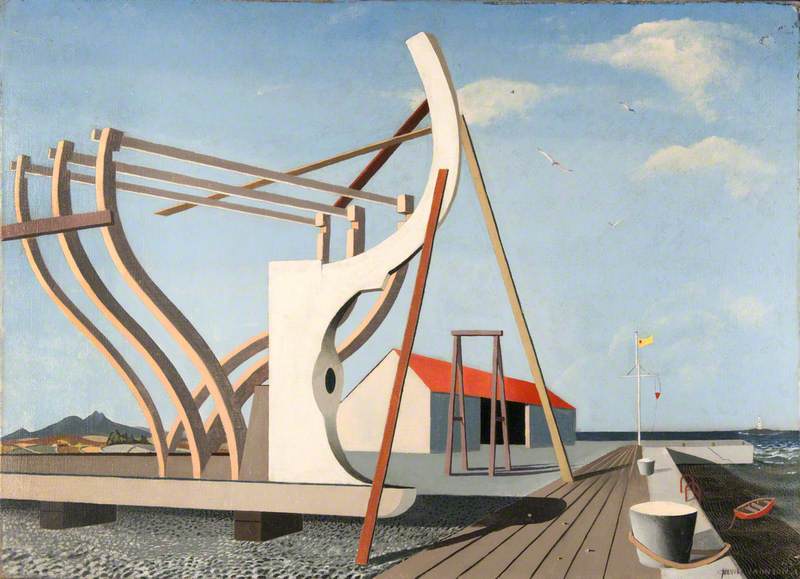

Not everybody was pleased. One disgruntled critic complained that ‘[Herman’s] miners and the women look like blotted, misshapen, prehistoric beings’. But many others admired his work, and in 1951 he was invited to create a major mural for the Minerals pavilion at the Festival of Britain. In the painting, six miners crouch in a row while a seventh stands to their left, linked to the group by a shadow that echoes the shape of the coal tip. Each figure is statuesque and suffused with a warm inner glow – they seem to embody the qualities of the mineral they mine. Herman was immensely proud of this painting, which is now housed at the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery. ‘All that preceded it found its culmination in this mural,’ he wrote. ‘All that followed it were not pictures but conceptions in monumental art.’

Josef Herman stayed on in Ystradgynlais for another four years, but in 1955, he moved on again, settling first in London, then in Suffolk. He also made various trips abroad to France, Spain, Israel and Mexico. But, as he put it: ‘Only Ystradgynlais changed my life and my work... When I left I took it with me.’ He was still painting miners from memory decades later, and he used techniques that he had perfected in Wales to depict farmhands, washerwomen and other workers around the world.

In the 1950s, Herman was a figure of considerable fame in the British art world. But his symbolic paintings slowly fell out of fashion as Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art and performance art rose to prominence. As rapid urbanisation and mechanisation transformed the countryside as well as the cities, Herman clung largely to his familiar traditional vision. This was deliberate: he wanted his paintings to speak to people on a different level. To him, art was a way of reconnecting with humanity in general, through time and across the world.

The eventual demise of the mining industry changed British life and politics forever. How will we remember its legacy as it passes into history? Last April, the UK ran for an entire day using only sustainable energy. In October, a Mining Art Gallery opened in the North East. Herman’s view of mining, his vision of an enduring way of life anchored in the land, seems of another age. But as twenty-first century life continues to evolve at a dizzying pace, it is well worth revisiting his Ystradgynlais.

Maggie Gray, art historian and writer