As Birmingham plays host to the Commonwealth Games this summer, there is a case for saying an artist who was brought up, educated and lived in the city, is a painter for our times. In a world riven by conflict and division, his work brings a gathered stillness, calm and a sense of place.

Joseph Edward Southall was born in Albert Street in the centre of Nottingham on 23rd August 1861 – the only son of Joseph Sturge Southall, a pharmacist, and Elizabeth Maria Baker. Both his parents were from distinguished Quaker families.

In September, the following year, aged 27, Joseph senior died, and so Elizabeth and her son moved closer to their extended family in Birmingham with Joseph coming under the guardianship of his uncle George Baker. To have relatives of the influence of the Bakers and Southalls was the greatest stroke of luck in a future artist's existence.

The Bakers were energetic industrialists and the Southall forbears were scientists and men of letters. Both families were campaigners and radicals and held in their hands an astonishing network of people, so that by an elaborate process of association, they could summon assistance for any challenge.

Joseph's Quaker education started at the Friends' School at Ackworth in Yorkshire, then Oliver's Mount in Scarborough and finally Bootham School in York. It was here he was first taught watercolour painting by the artist Edwin Moore, the son of the portrait painter William Moore. All of Joseph's schools had encouraged the study of the natural world and the recording of it through literature and art.

On 1st September 1878, a few days after his seventeenth birthday, Joseph began an apprenticeship at the offices of the Birmingham architectural partnership of Martin and Chamberlain. They were renowned for their Gothic Revival style of building inspired by The Stones of Venice, the seminal work of John Ruskin on Italian medieval architecture.

During the next four years, he continued his apprenticeship and studied art at evening classes, first at Osier Street Board School and later at the Birmingham School of Art, reading all that he could on the writings of John Ruskin and William Morris.

William Morris's case for the centrality of art in life especially appealed to him – art was not a matter of paintings on the wall. It was in the detail of everyday life including in the design of household goods. It was so omnipresent there was no need to define it.

After his apprenticeship at Martin and Chamberlain drew to a close, in the spring of 1883 he journeyed to Italy for the first time, travelling through Tuscany and Umbria in the company of his mother.

They visited the great centres of classical, Renaissance and Baroque architecture and art, studying the work of the Quattrocento master Fra Angelico and the other Italian 'primitives'. It was the work of Carpaccio's paintings in San Giorgio degli Schiavoni in Venice and the early Renaissance artist Benozzo Gozzoli at Pisa who sparked his interest in painting in tempera.

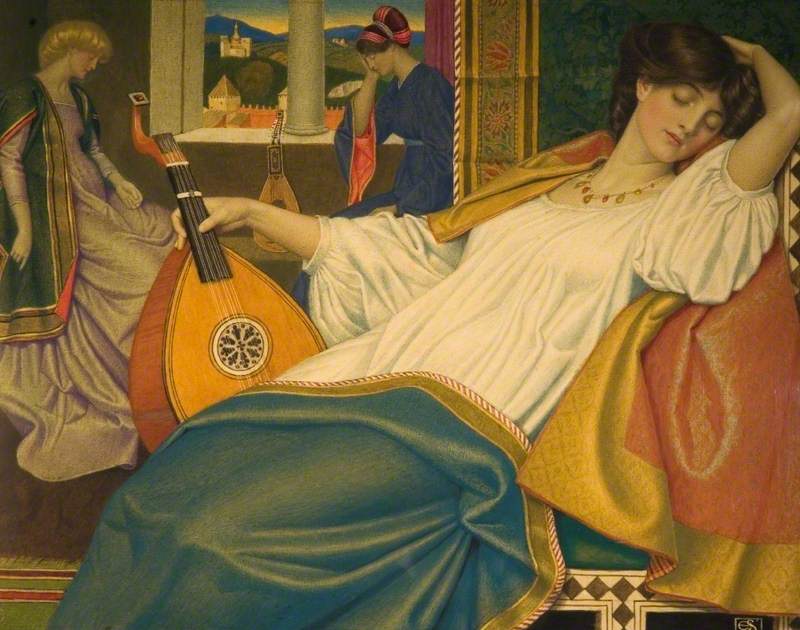

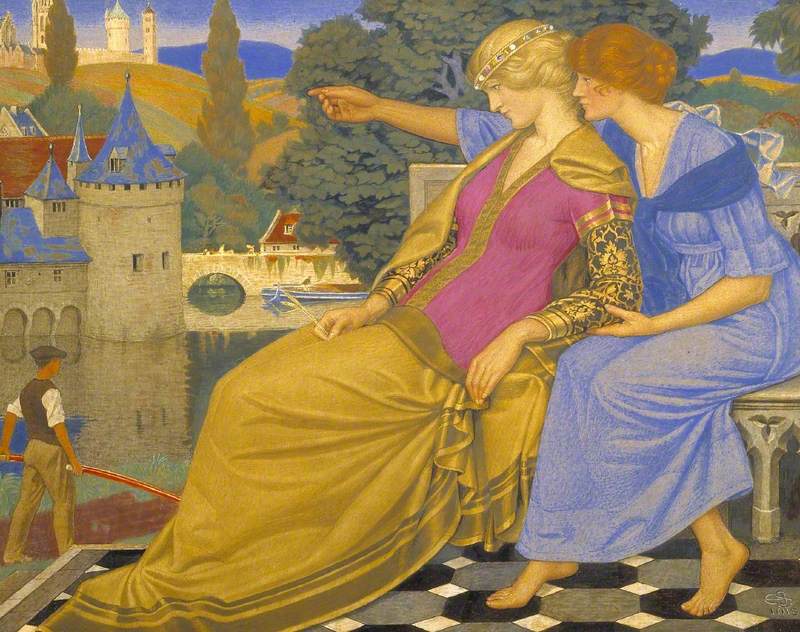

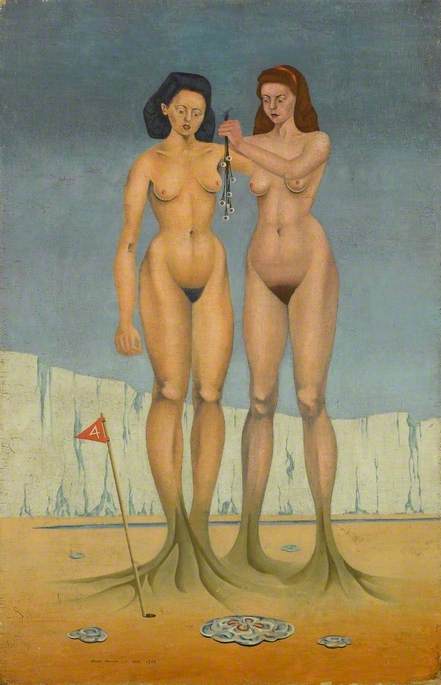

Beauty Receiving the White Rose from Her Father

1898–1899

Joseph Edward Southall (1861–1944)

On his return, Southall began his full-time arts education at the Birmingham School of Art, then under the inspired leadership of its headmaster, the artist and arts educator Edward R. Taylor. Taylor believed an artist should be rounded enough to make and paint with thought and care, a philosophy intended as a soulful reproach to the gimcrackery of industrialised batch production.

Not surprisingly, the school pivoted around William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones who had been born and raised in the city, and had been sensitised since childhood to art's role as a weapon against industrial grime and Victorian utilitarianism.

It was here that Joseph first met Arthur Gaskin, who would go on to become a lifelong friend. Joseph was the more proficient draughtsman out of the two and worked with extreme care and patience – attributes which were surely needed as he strove to perfect a recipe for painting in tempera in the way of the Italian 'primitives'.

There was very little literature on the subject, apart from Charles Eastlake's 1847 publication Materials for a History of Oil Painting and Mary Philadelphia Merrifield's 1844 translation of the early Renaissance artist and writer Cennino Cennini's Il libro dell'arte from c.1400, much was down to observation and guesswork.

Now 23 years of age, Joseph had moved into a house of his own at 13 Charlotte Road, Edgbaston, a property gifted to him by his uncle. It was during his second term as Lord Mayor of Birmingham in 1877 that Baker had invited John Ruskin to stay at his house and so had Ruskin's ear but also knew his critical eye. At a convenient moment in 1884, George had sent him some of his nephew's drawings made at the time of his tour of Italy.

Sufficiently impressed by his draughtsmanship, Ruskin handed Southall a commission to design a museum on the 22 acres of land at Bewdley in Worcestershire, which his uncle had given to Ruskin's arts and educational charity, the Guild of St George.

Sometime after this meeting, Joseph travelled to Italy (a trip most likely financed by Ruskin) and, among other places, again visited Pisa to study the Campo Santo artists. The idea that this group were nature's conduit was first proffered by Ruskin who believed the dazzling, mosaic-like vitality of early Christian Italian art possessed an emotional register absent in the chillier, more classical vision of Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo and Raphael.

Southall later visited Ravenna, where the city's mosaics were a key inspiration for Edward Burne-Jones's sinuous figures and decorative brilliance, which at once looks back to Byzantium and forward to Art Nouveau. In the end, nothing came of the museum and the commission was cancelled.

Coincidentally, Burne-Jones would go on to champion Joseph's ability as an artist. Again, it was George Baker who acted as matchmaker. He had commissioned Burne-Jones to design four stained glass windows for his mansion of Beaucastle in Bewdley, the ultimate Arts and Crafts fairytale creation. It was most likely Burne-Jones, too, who reiterated to Joseph his Renaissance forebears' rigorous philosophy that beauty held the key to Christian virtue – a philosophy he had adhered to while studying theology at Oxford University.

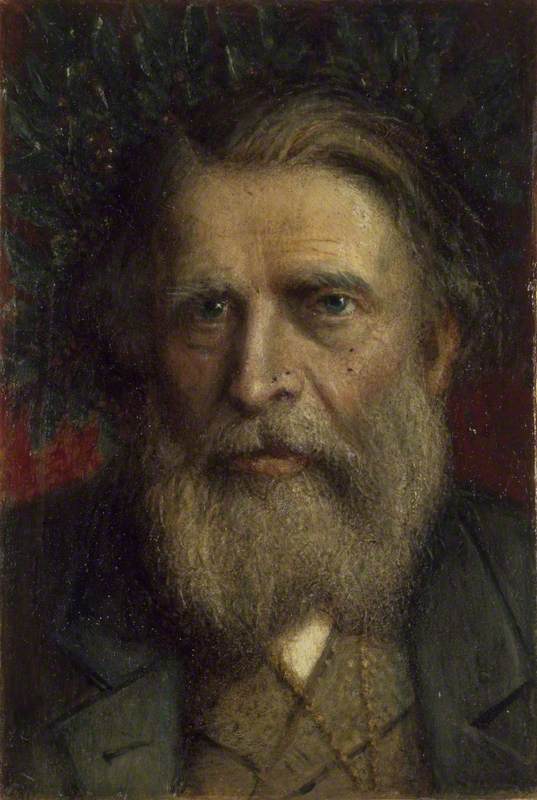

Southall's continuing good fortune in the art world owed something to the generosity and enthusiasm of Burne-Jones. Although he never used the medium, Burne-Jones was an enthusiastic ambassador for bringing back the use of tempera. In 1897, Southall produced three works in tempera including a self-portrait Man with a Sable Brush and 'Gismonda' (or Sigismonda...) which was painted in Burne-Jones's studio.

These pictures were subsequently submitted by Burne-Jones on Southall's behalf to the New Gallery in London, the successor to the Grosvenor Gallery, that same year. They were received with great acclaim by critics and the art-interested public.

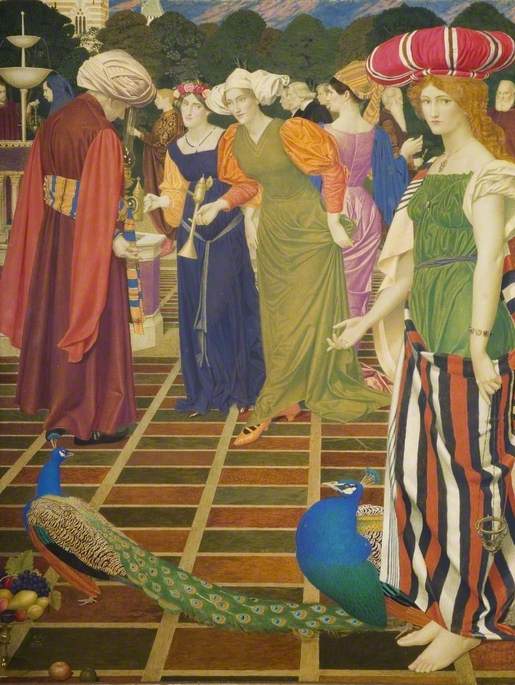

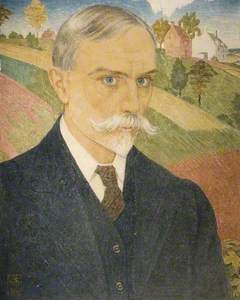

Beauty Seeing the Image of Her Home in the Fountain

1897/1898

Joseph Edward Southall (1861–1944)

This led to his involvement in various exhibitions including one at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society and of Modern Paintings in Tempera at Leighton House. The latter was effectively the launchpad for the foundation of the Society of Painters in Tempera, co-founded by Christiana Herringham and others, including Southall, in 1901.

Two years later, Southall married Anne Elizabeth Baker, his first cousin. They had been engaged for a number of years and Bessie (as she was known) frequently prepared Joseph's panels with gesso, stretched linen or silk for him to paint onto and gilded his frames.

Southall considered it essential to be involved in every step of the artistic process to ensure the quality of his artwork. This included designing and carving his own frames (he also designed furniture and was considered an expert embroiderer at the Birmingham School of Art), and even keeping poultry to guarantee a steady supply of fresh eggs.

In January 1910, as he made final preparations to show his work in France at the Galeries Georges Petit that spring, his mentor and guardian George Baker died. His uncle had closely followed his nephew's career, and had given him opportunities, encouragement and money.

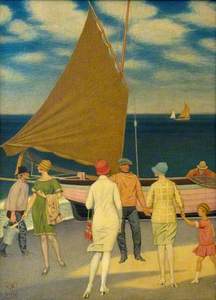

The exhibition in Paris was an astounding success not only in the number of paintings sold but also from an artistic standpoint. As a sign that the success of the exhibition was also down to Bessie's involvement, Joseph painted a double portrait of them walking on Southwold beach. In Bessie's hand is an agate, the stone used in the final process of gilding, to create a bright mirror finish.

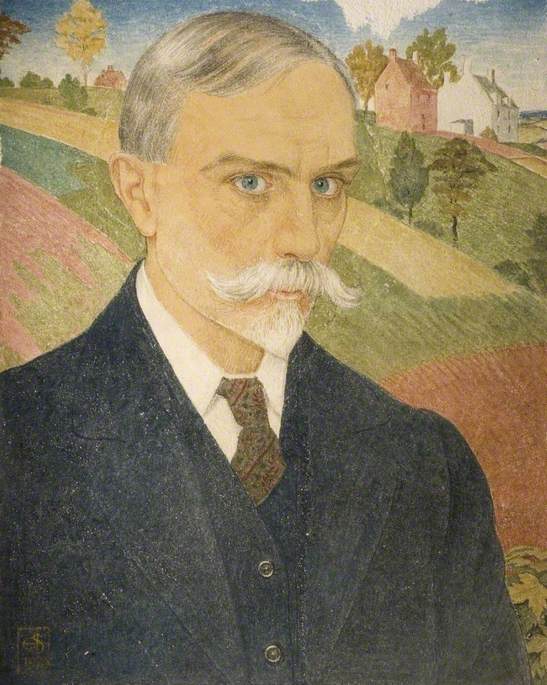

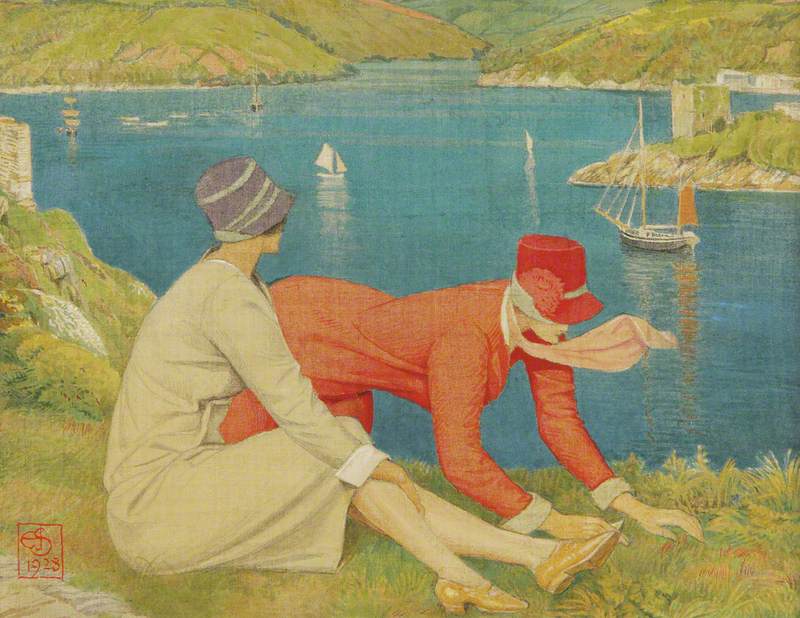

Joseph Southall and Anna Elizabeth Southall

1911

Joseph Edward Southall

The years leading up to the beginning of the First World War were the zenith in Joseph Southall's career. His technical mastery in tempera brought prestigious commissions, increasing artistic networks and recognition. He taught lessons and gave lectures both domestically and abroad. His work was widely exhibited in Britain, Europe and he also exhibited in America.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Southall followed his Quaker principles in arguing for peace and devoted much of his spare time to pacifism. In 1914, he was commissioned to paint a fresco for the staircase of the entrance to the Birmingham Art Gallery, 'Corporation Street, Birmingham in March 1914.'

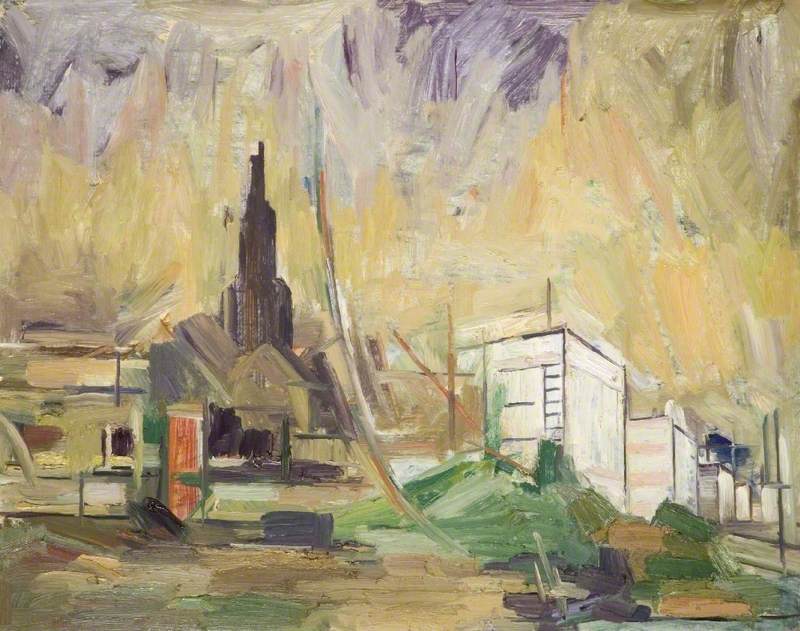

Corporation Street, Birmingham in March 1914

1914, fresco by Joseph Edward Southall (1861–1944). Situated at the top of the staircase at the entrance to Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery

Joseph's painting for the 11th Annual Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society at the Royal Academy in 1916 was titled The Return of Peace. It no longer survives but records of initial sketches indicate that the work was a colossal size at over 20 feet in height, and in a similar style to Belgium Supported by Hope.

When peace did return, life for Joseph and Bessie returned to a familiar pattern of overseas trips to Italy and France, interspersed with extended painting holidays in Southwold in Suffolk and the Fowey estuary in Cornwall. In 1926, the French recognised his technical mastery and significance and made him an associate of Les Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

A highlight of the interwar years, for him, was the 1930 Royal Academy Winter Exhibition where the South Rooms of the Royal Academy were, for the first time in its history, devoted to paintings in tempera. Southall's entry, The Return, was later bequeathed to Nottingham City Art Gallery.

In 1937, after a tour of Venice, Joseph was taken ill and underwent major surgery. He went steadily into decline, and although he doggedly stuck to painting cycles and continued to exhibit work throughout Britain and overseas, time was moving too fast. On 6th November 1944, Joseph died at his home in Edgbaston. The news of Southall's death was carried on the front page of the next day's Birmingham Post.

The poet and dramatist John Drinkwater, who had known Joseph Southall for many years, said: 'the people who complain that Southall's work had not the realism, or the muscularity of this, that or the other are not really saying anything about Southall at all. He was an artist who added a personal contribution of genius to the world of painting.'

Richard Morris, art historian – with thanks to Victoria Ward

Further reading

Joseph Southall 1861–1944, Artist, Craftsman, Birmingham Art Gallery catalogue, 1980

Patrick Dietemann, Wibke Neugebauer, Eva Ortner, Renate Poggendorf, Eva Reinkowski-Häfner and Heike Stege (eds.), Tempera Painting: 1800–1950 Experiment and Innovation from the Nazere Movement to Abstract Art, Archetype Publications, 2019

This story was updated on 12th August 2022 with thanks to George Breeze