Lucian Freud (1922–2011) painted eight portraits of his first wife, Kathleen 'Kitty' Garman (1926–2011), between 1947 and 1951. Girl with a Kitten (1947), one of 100 artworks included in my new book, Look At This If You Love Great Art – is among the most unsettling.

You would think that paying attention to minute details – a cluster of eyelashes, the folds of a lower lip, wisps of hair – would make a portrait more realistic. And yet, Freud's razor-sharp precision threatens to strip his sitter of her essence.

Kitty is shown against a beige wall, squeezing a kitten by its neck. She gazes blankly to the side, her stare cold and distant rather than tender, her knuckles turning white as she tightens her grip. There's a stark similarity between her and the young feline: both have wide, upturned eyes, reflecting the light; Kitty's straight dark eyebrows are mirrored in the kitten's markings; its pale paws, which look as if they've been dipped in cream, match her pallid fingers.

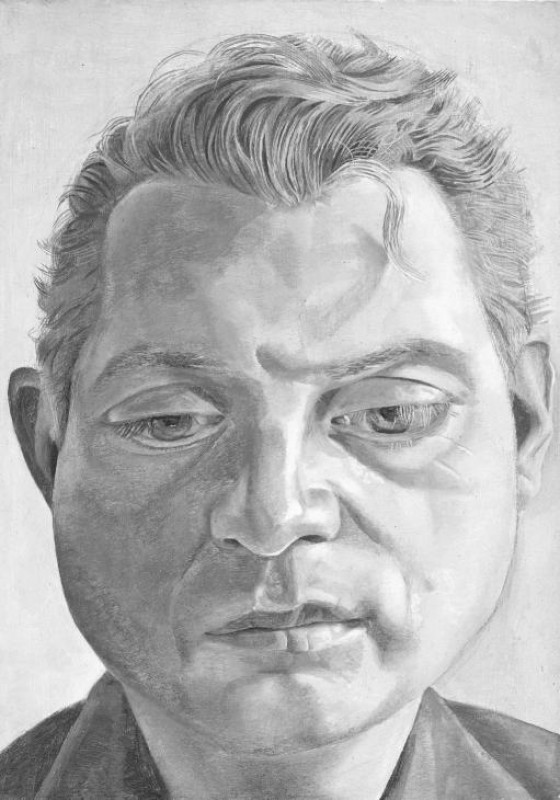

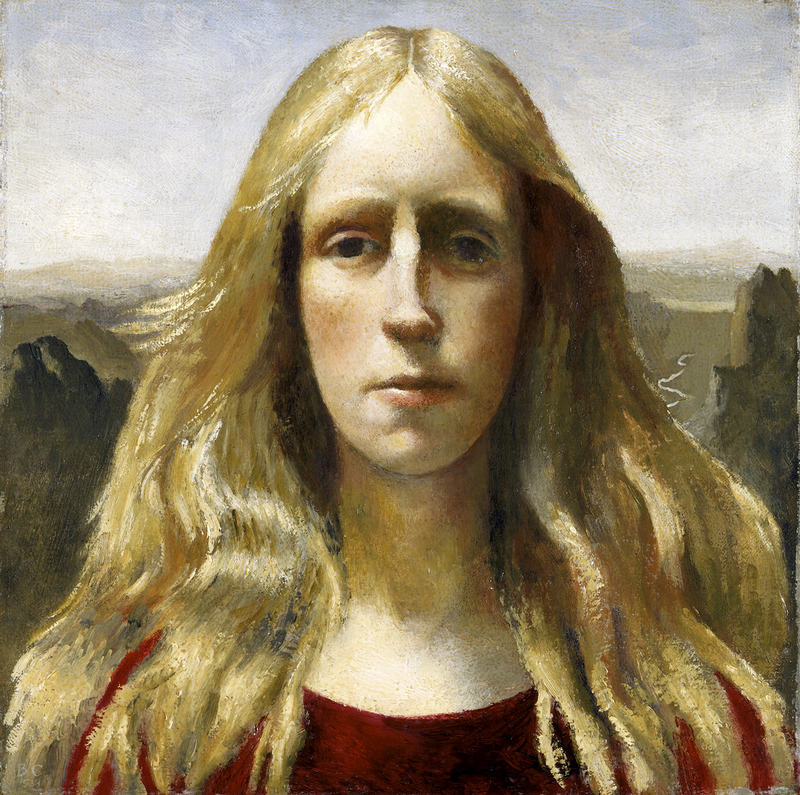

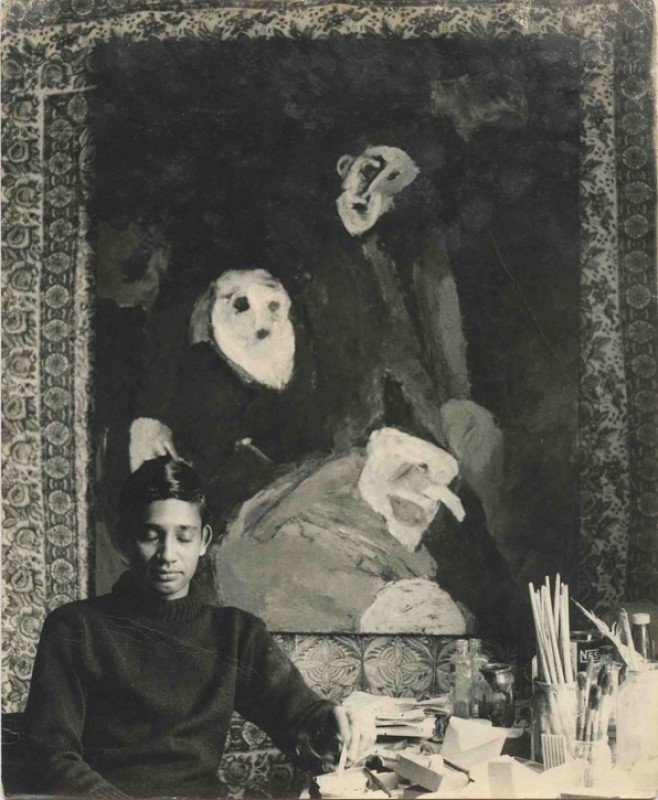

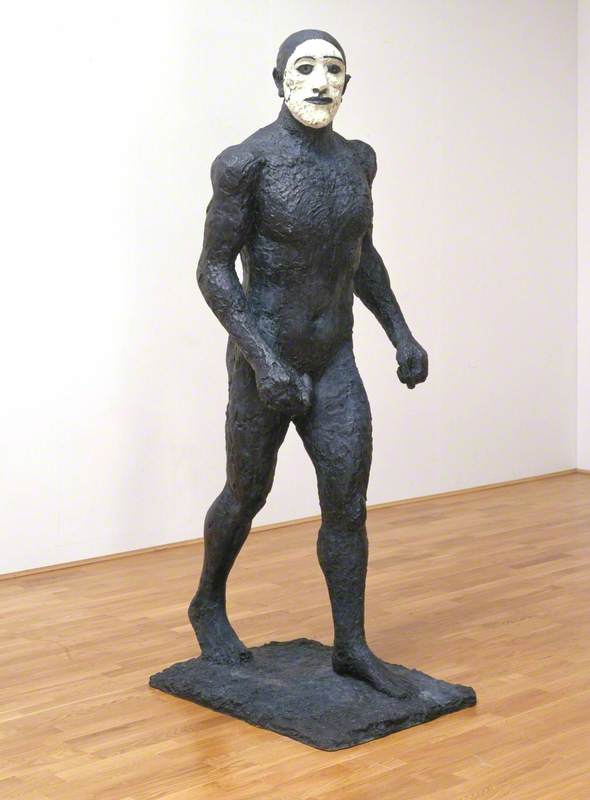

Kitty was well practised at sitting patiently for her portrait. The eldest daughter of the American-born twentieth-century sculptor Jacob Epstein and his lover, also called Kathleen Garman, she frequently modelled for her father. Here she is in bronze, cast in 1944, with a thick tumble of curls and those same wide-open eyes.

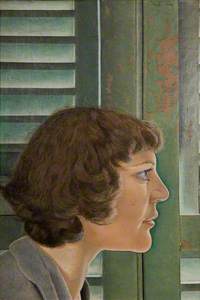

A few years later, her hairstyle has changed, but her expression remains fixed in time.

In Freud's Girl with a Fig Leaf (1947), Kitty hides behind a natural mask. The wavy leaf covers the majority of her face, drawing extra attention to her tweezered eyebrow and single unblinking eye.

Kitty and Freud married in February 1948, and in the same year, he painted the confrontational Girl with Roses. Newly pregnant, his young bride sits stiffly, with an ashen face, a glimmer of teeth visible between her lips.

Unfazed by its thorns, she clutches a two-toned rose – another lies limp in her lap. This pink-and-yellow breed was renamed the 'Peace Rose' at the end of the war, making it less of a love token and more a prickly reminder of bloodshed.

In the more lovely, less unnerving Girl with a White Dog (1950–1951), Kitty is pregnant with the couple's second child.

Both the setting and Kitty's casual attire, not to mention the way her yellow robe appears to have slipped off her shoulder to reveal her right breast, give the impression that this later portrait is also more intimate. But her expression remains vacant, the work's title anonymous.

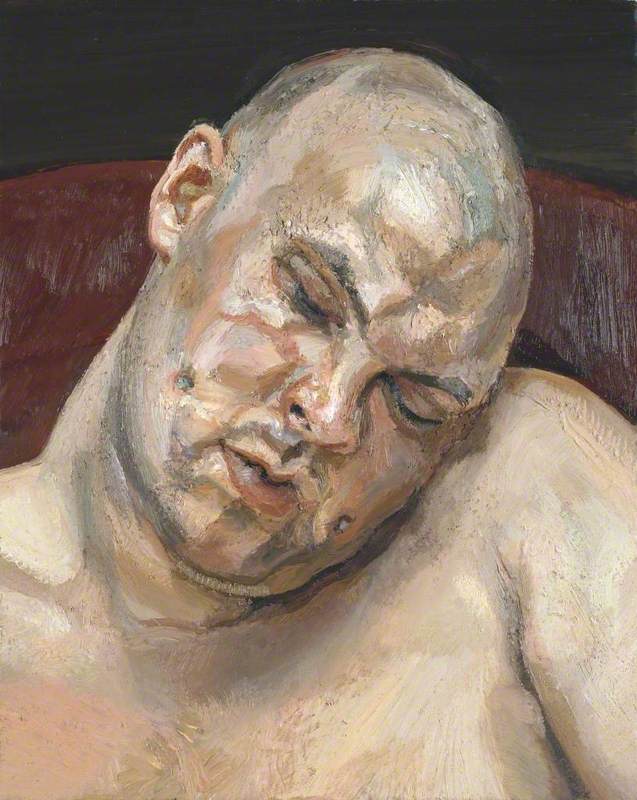

Freud once said that his early portraits were the result of his 'visual aggression' with sitters, that he would make both them and himself uncomfortable by sitting up close and staring. As for their scrupulous nature, he explains, 'I was trying for accuracy of a sort. I didn't think of it as detail. It was simply, through my concentration, a question of focus. I always felt that detail – where one was conscious of detail – was detrimental.' He sought to depict the world as it was, complete with imperfections, free from flattery.

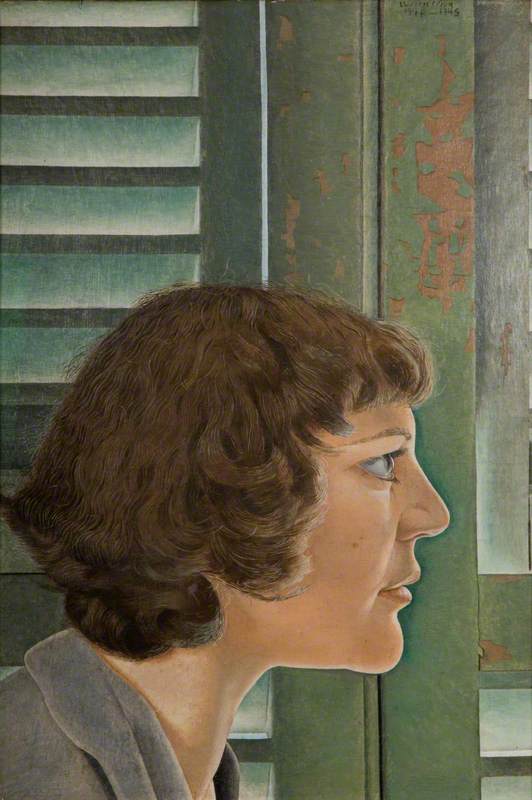

In Kitty (1948–1949), the peeling paint of the olive-green shutters commands as much attention as his wife. His approach was ruthlessly objective.

All of Freud's portraits of Kitty exude both fragility and strength, two qualities, coincidentally or not, in keeping with her upbringing. A child born out of an affair, she grew up in an unheated studio in Bloomsbury before being sent to live with her grandmother, Margaret, in Hertfordshire.

In 1923, Epstein's first wife, with whom he lived in London, shot Kathleen (Kitty's mother) in the shoulder with a pearl-handled pistol.

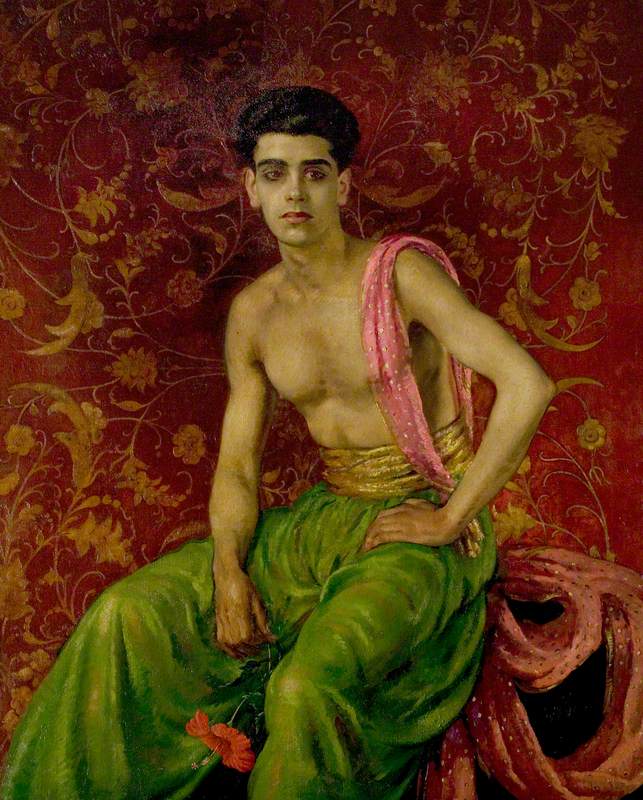

Kathleen Garman (1901–1979)

1935

Jacob Epstein

That Kitty believed the incident happened while she was in the womb paints her as a survivor. Her brother Theo, who struggled with his mental health, died of a heart attack in 1954, and nine months later her younger sister Esther killed herself. Of her siblings, Kitty was the only one to live a long life.

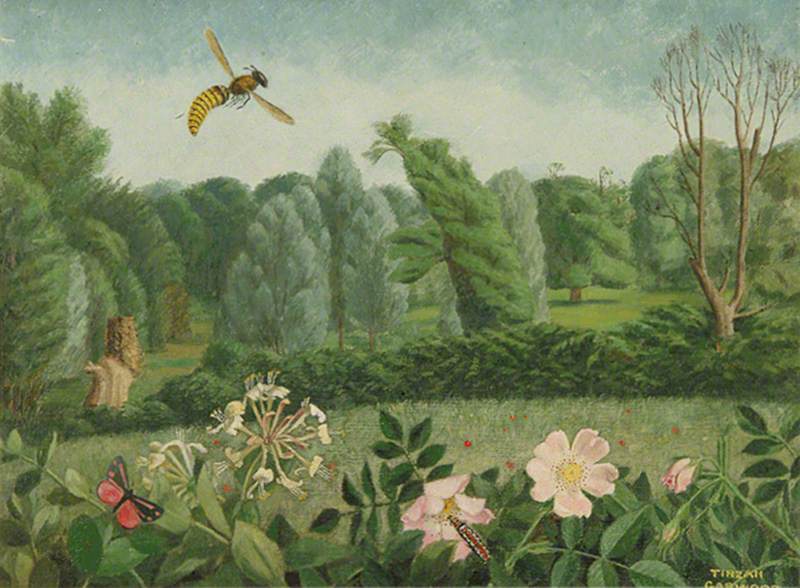

As well as a muse, she was an artist. In her late teens, she studied painting under Bernard Meninsky at London's Central School of Arts and Crafts. Discouraged by her mother, she put away her brushes, but in later life, she produced delicate pencil drawings and watercolours of plants and landscapes.

In the closely cropped Girl with a Kitten, Kitty's skin is like porcelain, tempting the viewer to reach out and tap it.

View this post on Instagram

She might not look particularly concerned as she half-strangles the kitten, with glazed-over eyes and parted lips, but she also doesn't look like she's enjoying it. The kitten, on the other hand, stares directly at us. In contrast with Kitty's flyaway hair, its whiskers remain neatly in place.

Like many of Freud's uncompromisingly exact early portraits, this one is almost too real, high definition. The ironic effect of such verisimilitude is that Kitty is sapped of life – it's the artist's merciless scrutiny that shines through here, far more than any feeling for his wife.

Still, the minuteness of detail is mesmerising. And the endangered kitten? An omen, perhaps: the marriage lasted just four years.

Chloë Ashby's Look At This If You Love Great Art is published by Ivy Press on 1st June 2021