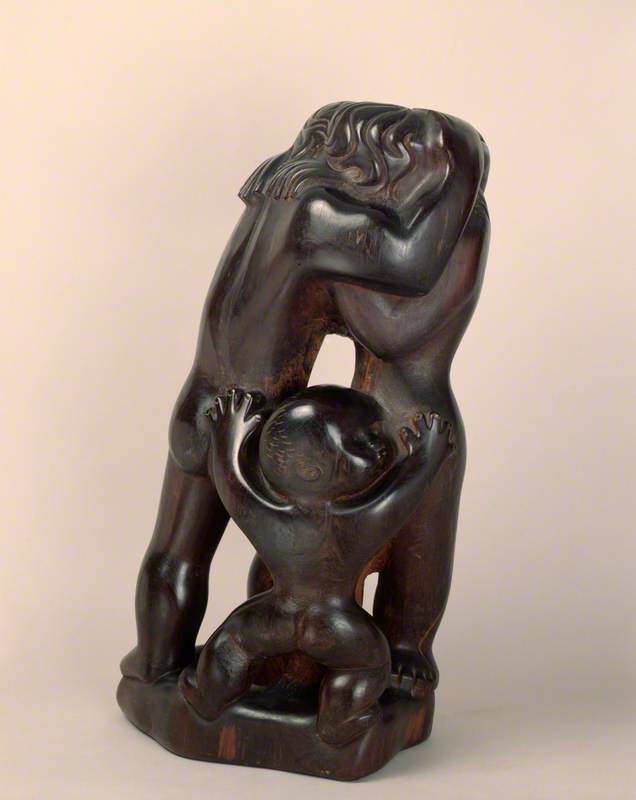

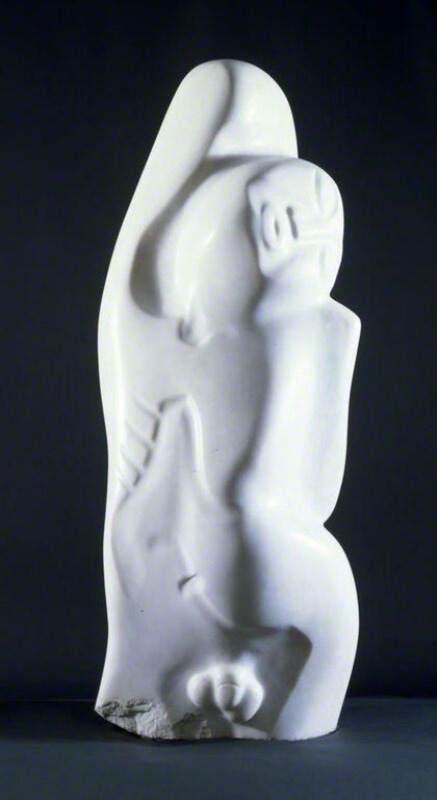

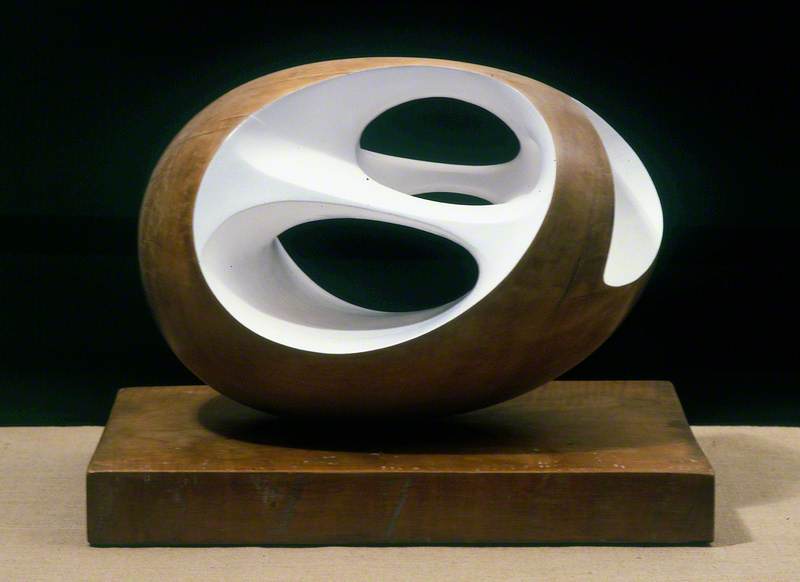

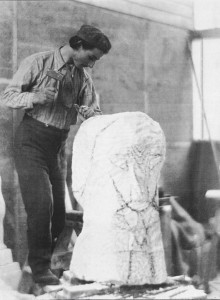

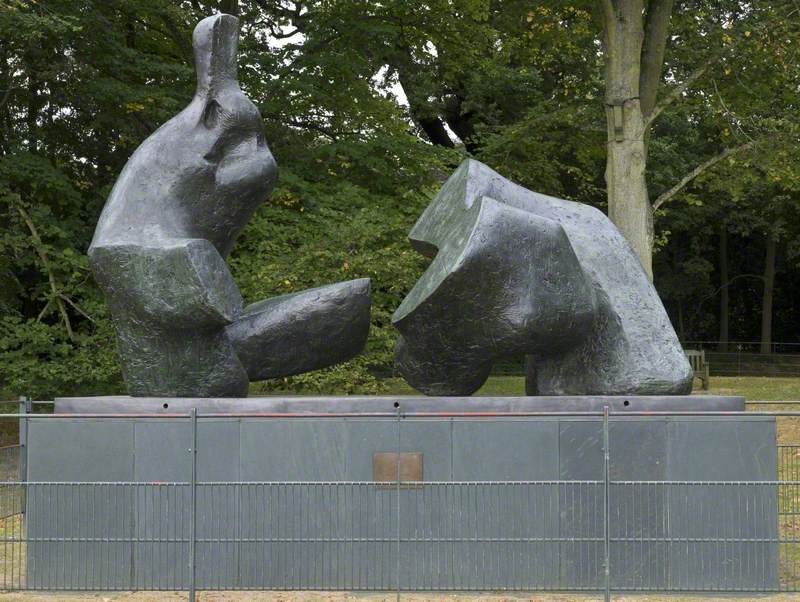

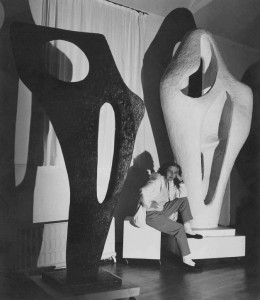

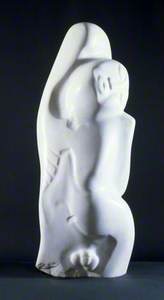

Leon Underwood (1890–1975) is best known today as a sculptor, being considered an important connection between the works of Gaudier-Brzeska, Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill before the First World War, and Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth (both of whom he taught) after the war. But his output was extraordinarily broad, and admirers are just as likely to come to him as a draughtsman, painter or indeed printmaker. His draughtsmanship – particularly his life drawing, and teaching of life drawing – was hugely admired in his lifetime. And his printmaking was innovative and influential, not least to the work of his students such as Blair Hughes-Stanton and Gertrude Hermes.

The perennial question in any consideration of Underwood is why someone of such art-historical 'significance' has been so relatively overlooked. Why is Leon Underwood not better known?

Commercial exhibitions have been few and far between. Blonde Fine Art held an exhibition of Underwood prints in 1992, The Redfern Gallery held a retrospective in 1996 and works have appeared in sales at Abbott and Holder, including a fine group of coloured linocuts. Pallant House staged its wonderful exhibition 'Leon Underwood: Figure and Rhythm' in 2015, publishing a typically scholarly and useful catalogue alongside. But that show was itself the first major survey of Underwood's art since 1969 and the sort of museum exhibition that John Rothenstein, Underwood's biographer Christopher Neve and others had been calling for since the 1970s.

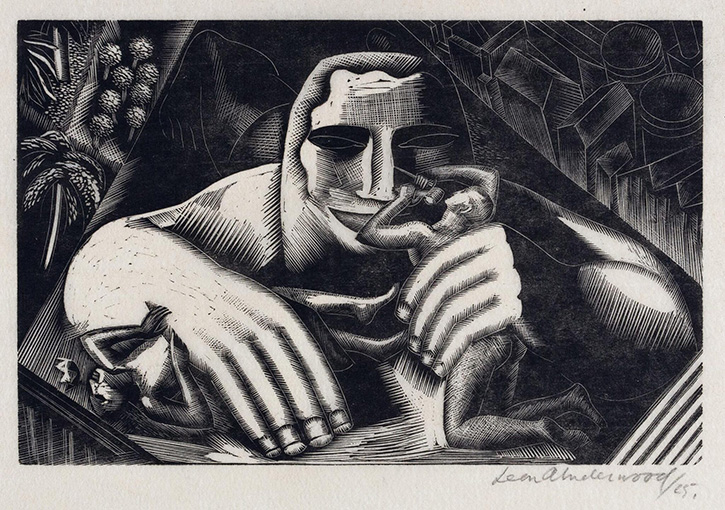

Pharaoh's Icon / Ceasar and the Slave

1925, wood engraving by Leon Underwood (1890–1975)

The fact is that Underwood's qualities are exactly what hampered his reception in his lifetime and in the years immediately following his death. He was a supreme technician in everything he did. But he was versatile to a fault, making it hard for critics and his audience to neatly categorise (and therefore quickly understand) him. He was a brave and intrepid traveller. But he seems always to have gone abroad at moments when his career and reputation would have benefitted from consolidation. Finally, he had deeply held beliefs on art. Regardless of one's taste, this gives his work an integrity and human quality. But his ideas – essentially that there should be a relationship between content and form in art, and that inspiration and intuition have a value over science and logic – ran counter to prevailing trends in artistic theory in the twentieth century, not least Modernism.

Underwood was trained at the Regent Street Polytechnic and then at the RCA from 1910 to 1913. In 1914 he travelled to modern-day Lithuania and Belarus, having to make a hair-raising journey home via Finland, Sweden and Norway as war broke out. He enlisted in the Royal Horse Artillery but was later transferred to the camouflage section.

In 1919 he attended a refresher course at the Slade and bought his studio in Girdlers Road, Hammersmith. From here he began to take students, often provided by Henry Tonks, who was oversubscribed at the Slade (Eileen Agar and Gertrude Hermes were two pupils he received this way).

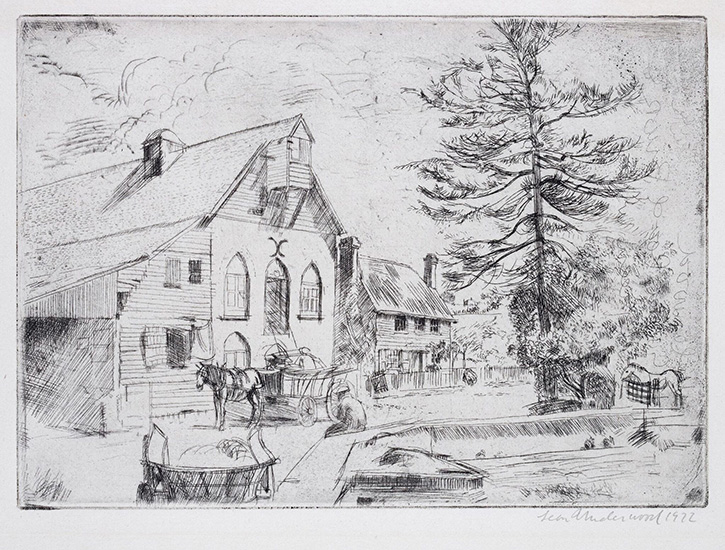

Kent; The Mill, Ashurst

1922, etching by Leon Underwood (1890–1975)

In 1920 he was awarded the Prix de Rome and joined the staff of the RCA as assistant master for life drawing. But Underwood, ever at odds with authority, fell out with William Rothenstein and resigned from his post in 1923. It was then he decided to use his Prix de Rome travel scholarship, once again cutting against the grain, to visit Iceland (rather than Italy) in the company of Blair Hughes-Stanton and Rodney Thomas.

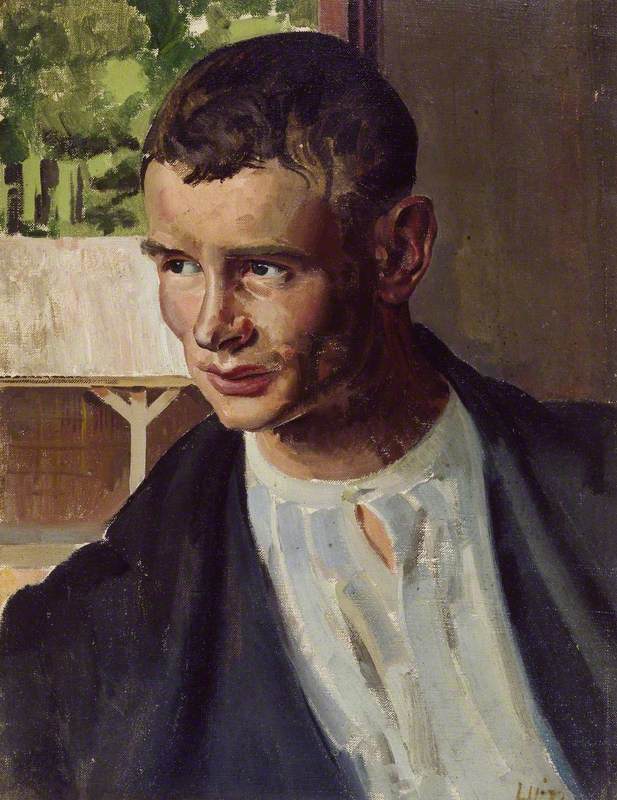

Underwood's Brook Green School of Art was formally established at his Girdlers Road studio in 1921. But it really came into its own on his resignation from the RCA in 1923, when Henry Moore and others persuaded him to carry on giving them life-drawing lessons in the evenings. The small and select roster of artists who were to become students of the Brook Green School of Art included Blair Hughes-Stanton, Gertrude Hermes, Nora Unwin, Mary Groom, Vivian Pitchforth, Raymond Coxon, Eileen Agar and Henry Moore.

'… except for Rothenstein there was only one teacher I learned anything from – Leon Underwood'. – Henry Moore

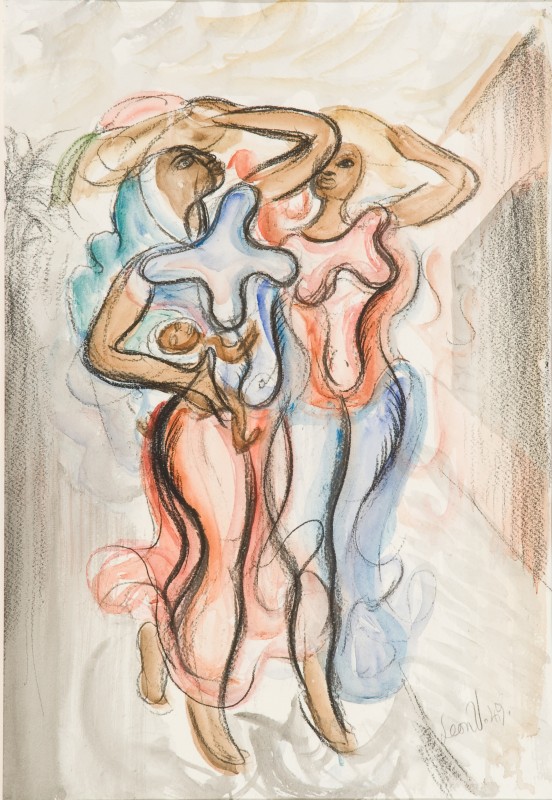

Eileen Agar said Underwood 'believed in the primacy of drawing, and indeed he taught little else at the Brook Green School'. While this may seem a traditional approach, Underwood's method of life drawing, and if teaching it, was anything but. While it may not be immediately obvious to us now, it was in stark contrast to that practised at the Slade and elsewhere. The whole ethos of the school was based on originality, practised in as informal a way as possible.

Drawing was very much taught at the school. But printmaking was explored together on equal terms.

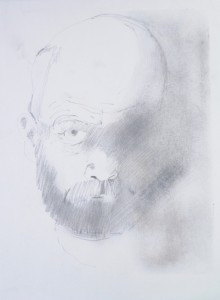

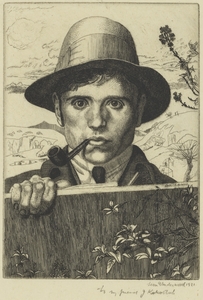

Underwood had himself studied printmaking under Frank Short at the RCA – although he was always adamant he learnt more from Short's assistant, Constance Pott – and had made a handful of etchings before and just after the First World War. In 1921, when he was himself teaching at the RCA, he used the acid baths there to make his great self-portraits, St Sebastian and Self Portrait in a Landscape. Frank Short, naturally, disliked these etchings. But they were well received elsewhere, and Underwood installed a press at Girdlers Rd. An intense period of etching followed culminating in an exhibition at the Chenil Gallery in 1922.

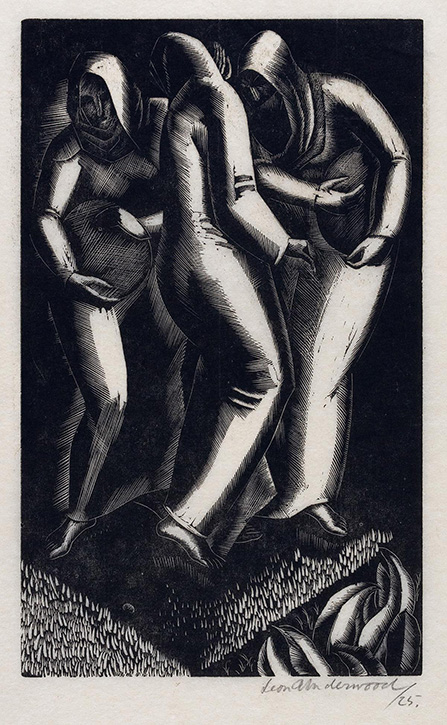

Three Peasants and a Lost Shilling

1925, wood engraving by Leon Underwood (1890–1975)

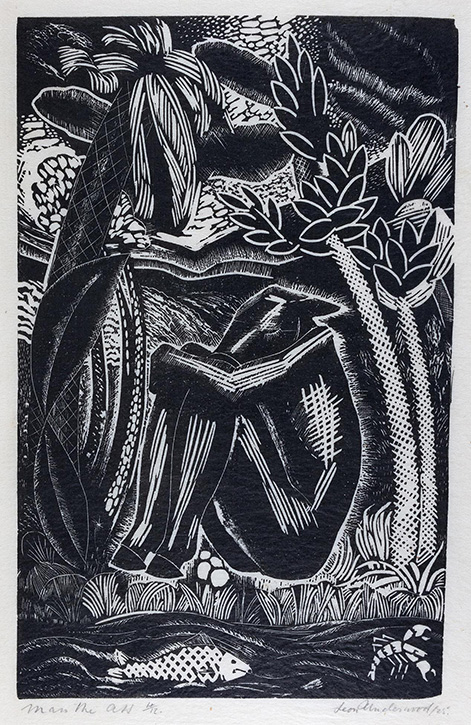

In 1923 wood engraving was introduced to the school by Marion Mitchell and a house style was soon established. This was marked by its experimental and expressive character and was in contrast to the arguably more 'craft' conscious work of artists such as Eric Gill.

Brook Green became a collaboration of artist-friends as much as a school and in 1925 Underwood and a group of them visited Dalmatia, Italy and then the Altamira caves in Spain. The pre-historic drawings Underwood saw there further consolidated his admiration for the art of 'primitive' cultures and his wonderful Human Proclivities of 1925 should be viewed in the light of this interest.

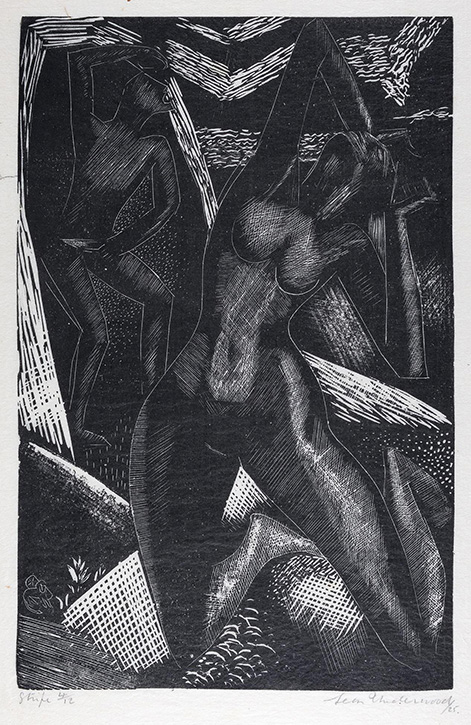

Human Proclivities: 'Strife'

1925, linocut by Leon Underwood (1890–1975)

The prints were made using a graver on lino, allowing Underwood to cut them freely and achieve great expressive effect while retaining the appearance of wood engravings. These impressions belonged to Underwood's pupil, the great printmaker Gertrude Hermes.

Human Proclivities: 'Man the Ass'

1925, linocut by Leon Underwood (1890–1975)

In 1925 Underwood, Hughes-Stanton, Hermes, Agar and Marion Mitchell felt their work was sufficiently different from their contemporaries to break away from the Society of Wood-Engravers and form the English Wood-Engraving Society. This group was relatively short-lived, only exhibiting together at the St George's Gallery until its closure in 1928. The graphic style of the Brook Green School instead found its culmination and ultimate expression in the early 1930s when they began publishing their magazine The Island, funded by Eileen Agar, and in which their work and philosophy of art (as espoused by Underwood) appeared.

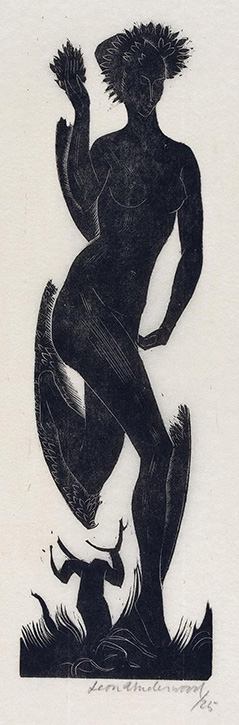

Daphne / Persephone

1925, wood engraving by Leon Underwood (1890–1975)

In 1926 Underwood travelled to the States, leaving Brook Green in the capable hands of Blair Hughes-Stanton. His intention was to capitalise on the boom in luxury house building in Palm Beach, for which he hoped to win commissions painting murals. The venture was a non-starter and he quickly moved to New York, initially attempting to support himself by selling some of the collection of African sculpture he had been making since 1919, but subsequently opening a school of art in Greenwich Village.

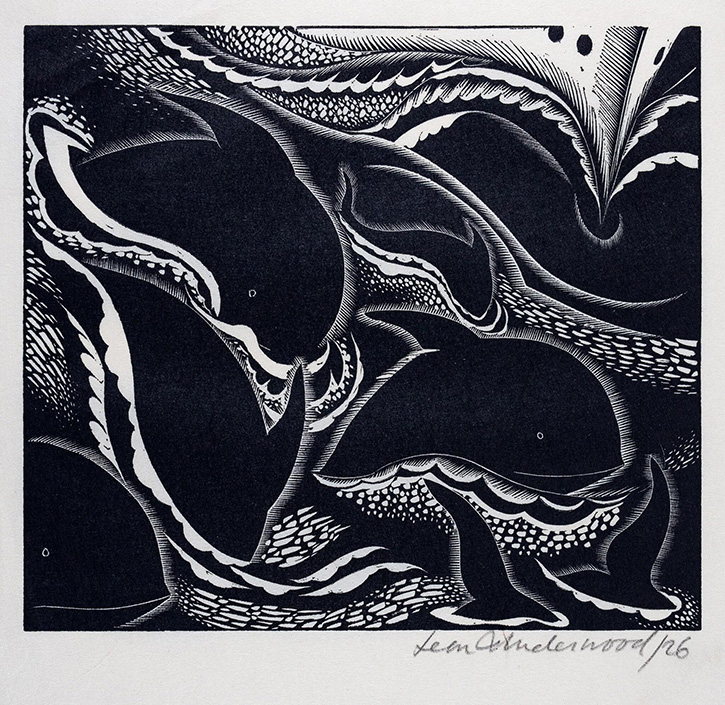

For almost the only time in his life, Underwood found his graphic style was in vogue, satisfying Art Deco taste and the dynamism and frivolity of the 1920s. He made illustrations for publishers including Brentano's, John Day, Vanity Fair and The New Yorker.

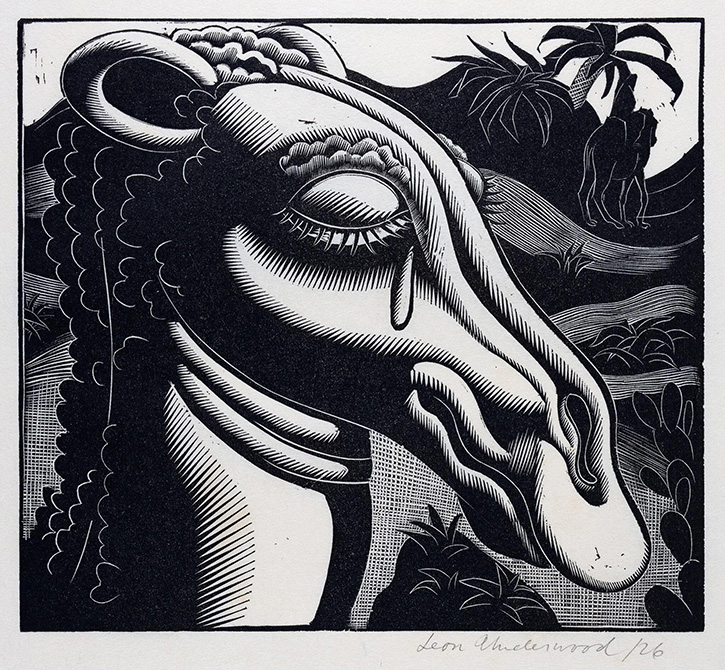

Camel

1926, wood engraving by Leon Underwood (1890–1975), for 'Animalia or Fibs about Beasts'

He also began to write and illustrate his own books. The first was Animalia; or Fibs about Beasts, published by Payson and Clarke in 1926. Dedicated to his son … 'To Garth / For whom cleaving facts asunder fall / And fancy sheds a healing light on all', this light-hearted but beautifully illustrated book won the New York Publisher's prize for book design. Underwood published an edition of prints which were shown at the English Wood Engraving Society's annual exhibition at the St George's Gallery, sharing a wall with works by Eric Ravilious.

Porpoise

1926, wood engraving by Leon Underwood (1890–1975), for 'Animalia or Fibs about Beasts'

Underwood's next book, The Siamese Cat, was written in England but he returned to New York in 1927 to hand the manuscript and illustrations to Bretano's for publication. It was then that Underwood and Phillips Russell (who had written the introduction to The Siamese Cat) proposed to the publisher that they be sent to Mexico to follow the route taken by writer and artist team John Stevens and Frederick Catherwood in 1839 and produce an illustrated account.

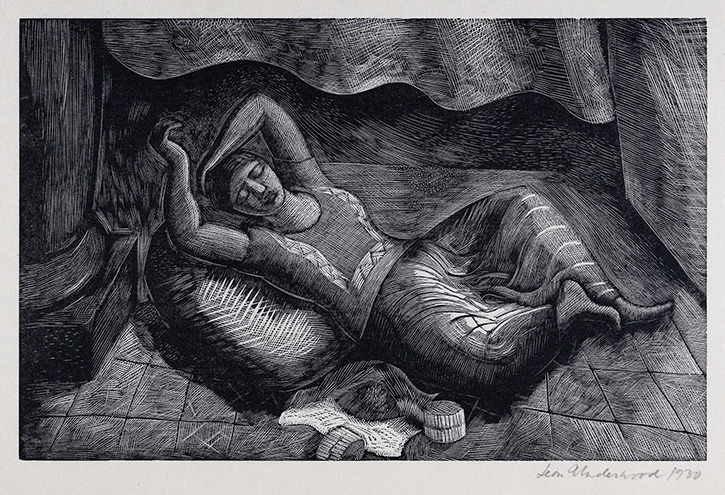

Cigarette Mater, Tehuantepec

1930, wood engraving by Leon Underwood (1890–1975)

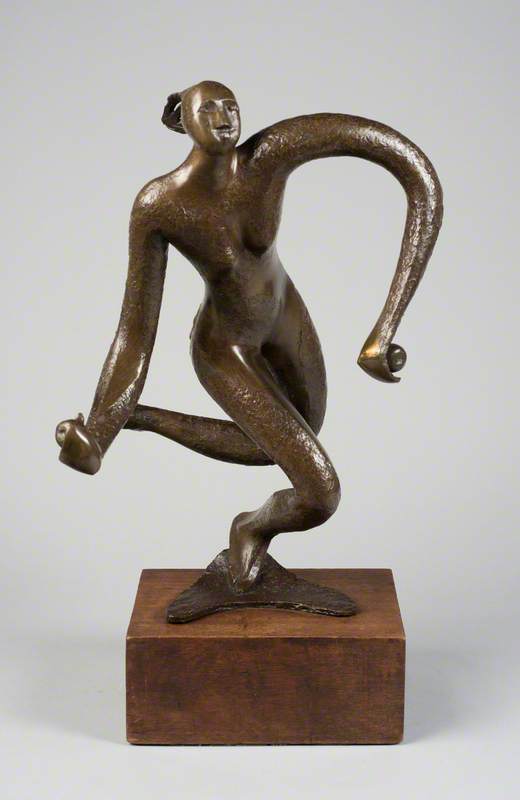

The pair arrived in Mexico in December 1927 and so began the most influential period of Underwood's life. The studies he made of Mayan and Aztec Art would have a profound impact on his work for the next decade.

Underwood's 'Mexican' works appear in all media, including illustrations made for Red Tiger: Adventures in Yucatan and Mexico, the reason for the trip. But simultaneously, he made a remarkable group of stand-alone wood engravings of Mexican subjects. Then in the mid-1930s, just as Underwood had suddenly moved from etching to wood engraving in the early 1920s, he turned to making large-scale coloured linocuts.

Pike Fishing

1936, linocut printed in colours by Leon Underwood (1890–1975)

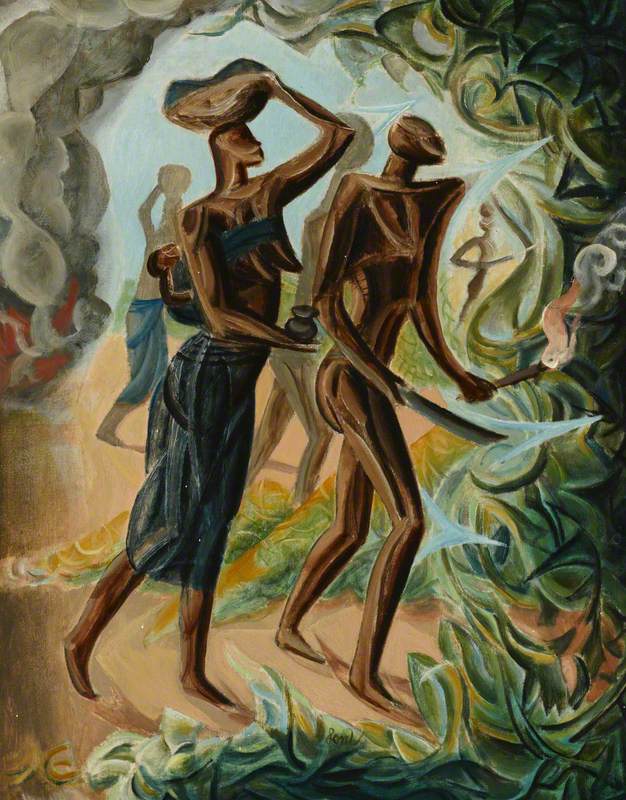

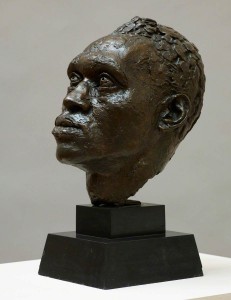

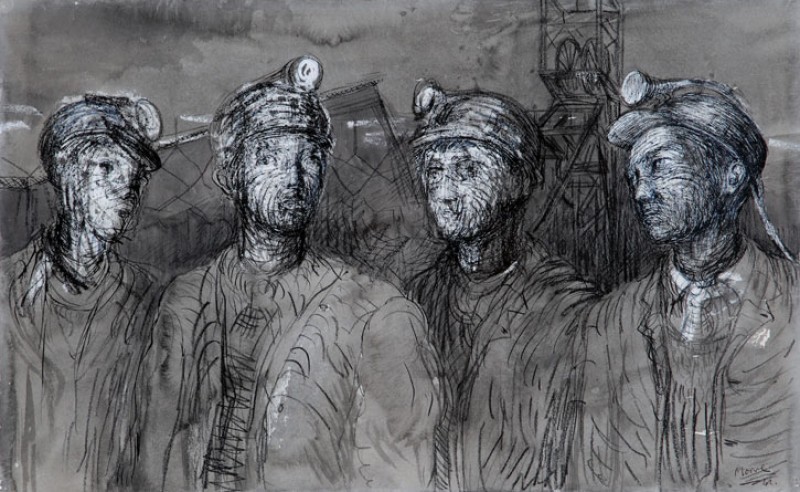

The Brook Green School of Art ended in 1939 and Underwood again went to serve in the Camouflage Unit. After the Second World War, he travelled to West Africa, lecturing for the British Council. Here he made one of the pre-eminent collections of African carvings, pottery and textiles, much of which is now in the British Museum.

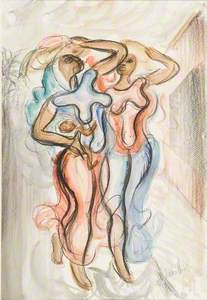

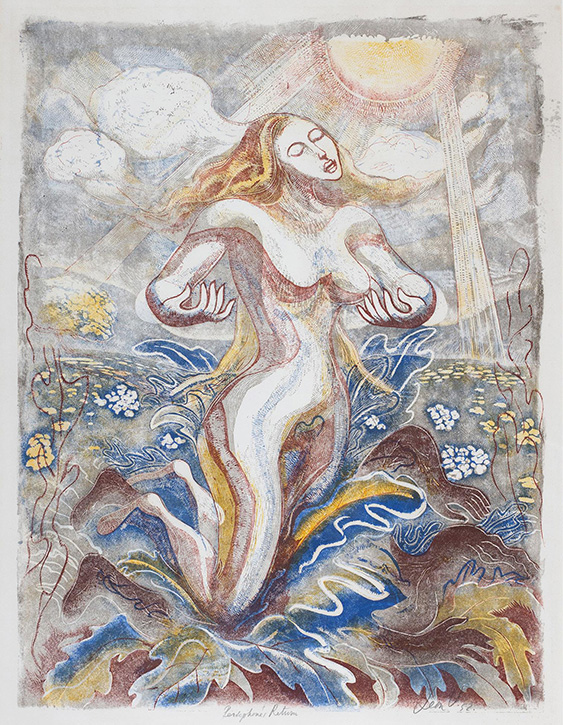

As Mexico had so influenced him in the 1920s and 1930s, the art of Africa now dominated his life and work. He wrote a number of books on African art in the 1940s, becoming a recognised authority in the field. He made new Africa-themed sculptures and continued to make large-scale linocuts, shown at an exhibition at the Beaux Arts Gallery in 1953. His printed figures of this date, if Western in first appearance, take on the sculptural form and exuberance of statuesque African carvings.

Persephone's Return

1952, linocut printed in colours by Leon Underwood (1890–1975)

This article only gives a broad introduction to Leon Underwood's remarkable life story, and mainly centres on his work as a printmaker – an exhibition of his prints is showing at Abbott and Holder until 7th October 2023. More information on the sale, and opening hours, are available on the Abbott and Holder website.

Tom Edwards, Owner and Managing Director at Abbott and Holder Ltd

Further reading

Jonathan Blond, Leon Underwood: Wood-engravings and Linoprints, Blonde Fine Art, 1992

Simon Martin (ed.), Leon Underwood: Figure and Rhythm, Pallant House, 2015

Christopher Neve, Leon Underwood, Thames and Hudson, 1974