'Love is merely a madness' – William Shakespeare, As You Like It

Throughout history, philosophers, writers and psychologists have viewed love as a malady – a kind of mania that can drive us to dizzying heights of euphoria, to the depths of despair, or even utter madness.

Whether or not you agree with this theory, I’m sure many of us can agree that Valentine's Day can be a rather nauseating social event. Red roses, heart-shaped chocolates, stuffed toys. It’s all one big cliché isn’t it? You'd have to be mad to buy that stuff – oh wait.

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

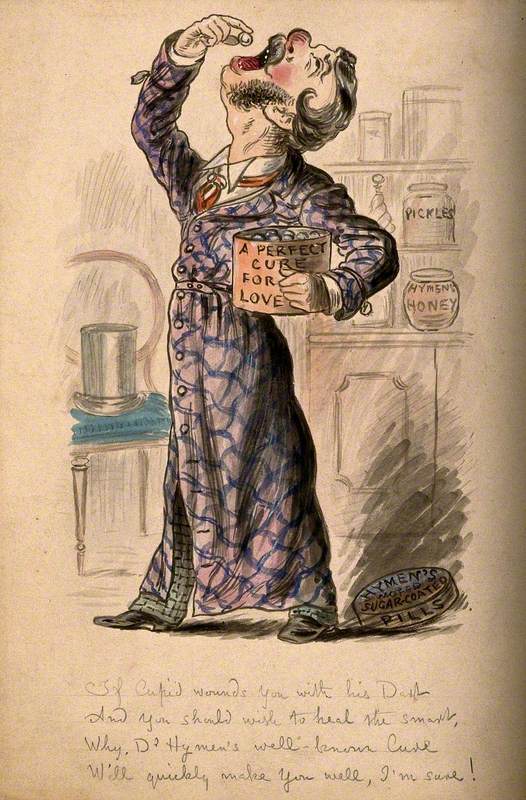

A Love-Sick Man Taking Some of Doctor Hymen's Pills to Try and Cure Himself

unknown artist

Wellcome CollectionWe're going to celebrate this annual event in another way, by considering how artists have depicted delusional lovesickness...

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

A Physician Taking the Pulse of a Lovesick Girl

Jan Steen (1625/1626–1679) (after)

Wellcome CollectionLove is blind

'Love is blind and lovers cannot see the pretty follies that themselves commit' – William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

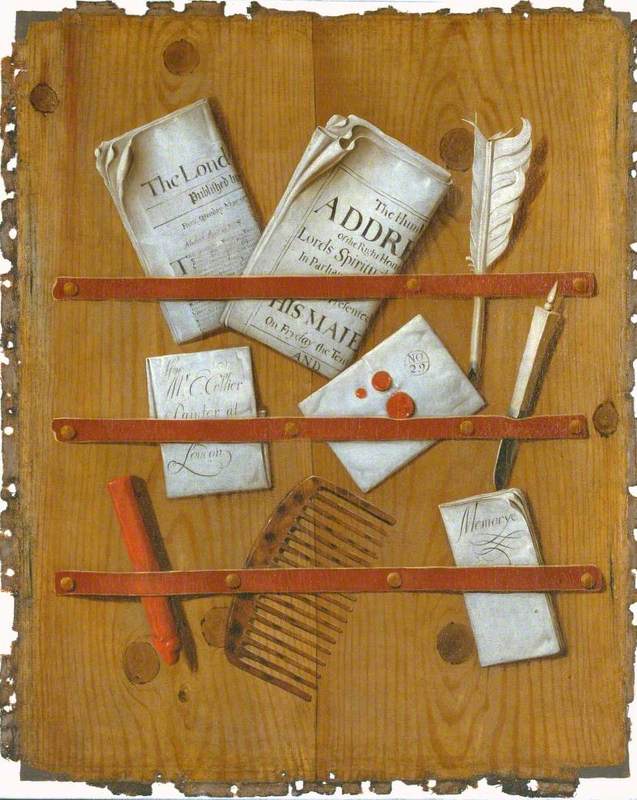

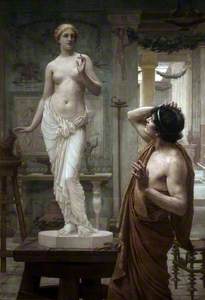

The expression 'love is blind' – essentially meaning that you can't help who you fall in love with – has endured for centuries. The aphorism is perhaps no better illustrated than in the classical story of Pygmalion, in which a sculptor falls in love with his own creation – a statue of a beautiful woman. In the story, Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, grants Pygmalion's wish and turns the ivory statue into a real-life woman. Pygmalion's erotic obsessions for an inanimate object become a reality (this is, like a lot of Greek mythology, quite disturbing by today's standards).

If it's possible to fall in love with a curvaceous block of elephant tusk, then love truly is blind.

The story of Pygmalion can be found in Ovid's Metamorphoses, which was later adapted into a play by the Nobel Prize-winning Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw. The classical narrative had a resurgence in popularity during the Victorian era, and artists such as the Pre-Raphaelite Edward Burne-Jones also painted Pygmalion. Shaw's play was the inspiration for the 1964 film musical My Fair Lady, in which Audrey Hepburn plays Eliza Doolittle – a loud-mouthed, yet loveable cockney flower girl from Covent Garden, who is given elocution lessons to be 'elevated' from her social class.

Image credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Love Animating Galatea, the Statue of Pygmalion c.1802

Henry Howard (1769–1847) (after)

Paintings CollectionThe idea and expression that 'love is blind' appears in many Shakespeare plays, in particular Romeo and Juliet, but was first used in Geoffrey Chaucer's Merchant's Tale.

Pygmalion and the Image: The Soul Attains 1878

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898)

Birmingham Museums TrustLove and melancholia

Image credit: National Trust Images

Mirth and Melancholy (Miss Wallis, Later Mrs James Campbell) 1788–1789

George Romney (1734–1802)

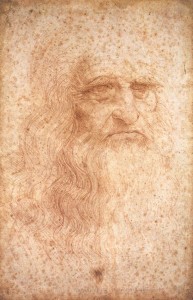

National Trust, Petworth HouseIn the twelfth century, the physician Gérard du Berry wrote extensively about the condition of 'lovesickness' which, he believed, was an imbalanced constitution due to the trauma of unrequited love. According to Berry, untreated lovesickness ultimately led to coldness and melancholia, a depressive condition also theorised by Robert Burton in his The Anatomy of Melancholy (1638).

Image credit: Brasenose College, University of Oxford

Robert Burton (1576/1577–1640) 1635

Gilbert Jackson (active 1615–1645)

Brasenose College, University of OxfordIn the medieval period, the condition of lovesickness was taken so seriously, medical treatments really did exist. Today we turn to terrible romantic comedies, ask Google for advice, try to avoid seeing our ex on social media, and probably eat disgusting amounts of ice cream. But in the medieval era, remedies included the root of hellebore, exposure to light, gardens, calm and rest, inhalations, and warm baths with plants such as water lilies and violets. (Actually, can we bring this type of love rehab back please?)

An excessive amount of 'black bile', which we today call sadness or melancholy, was symptomatic of lovesickness, treated through purgatives, laxatives and blood-letting. (Maybe don't try any of these at home.)

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

A Surgeon Binding up a Woman's Arm after Bloodletting 1666

Jacob Toorenvliet (c.1635–1719)

Wellcome CollectionIn fact, the notion of the 'four humours' was taken from Hippocrates, Galen and other ancient physicians. It was an idea that persisted until the Middle Ages. The four humours were described as melancholic (black bile), phlegmatic (phlegm), choleric (yellow bile) and sanguine (blood). It was believed that the

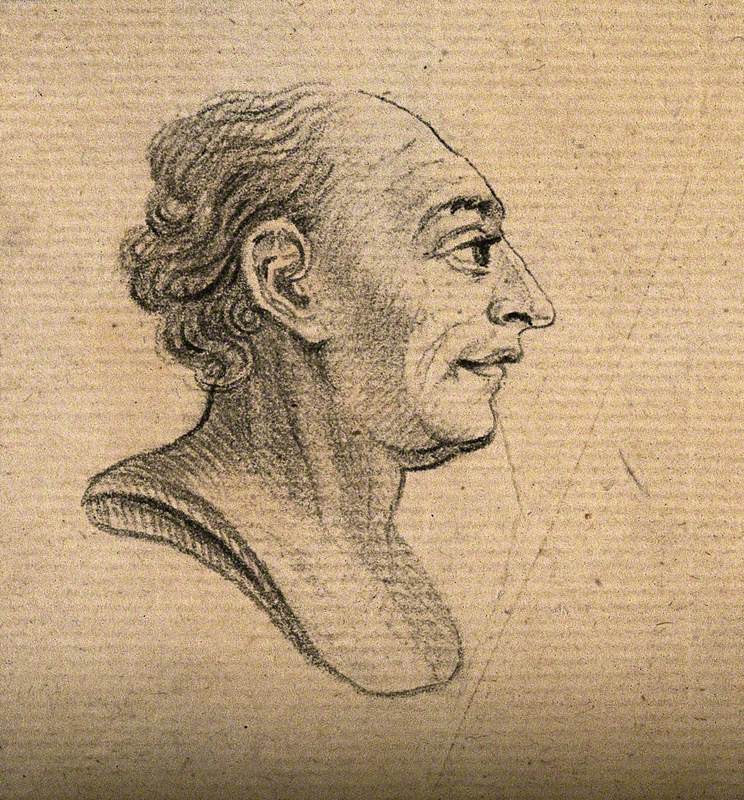

Image credit: Wellcome Collection

A Bust Showing a Phlegmatic-Sanguine Temperament c.1792

Thomas Holloway (1748–1827) (associated with)

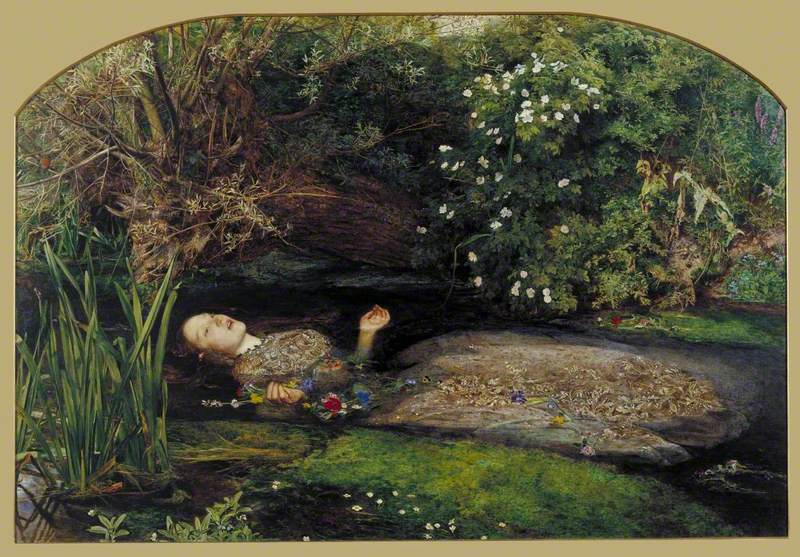

Wellcome CollectionFor Shakespeare, melancholy was the most complex of emotions, exemplified by his tragic character Ophelia, whose unrequited love for

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder

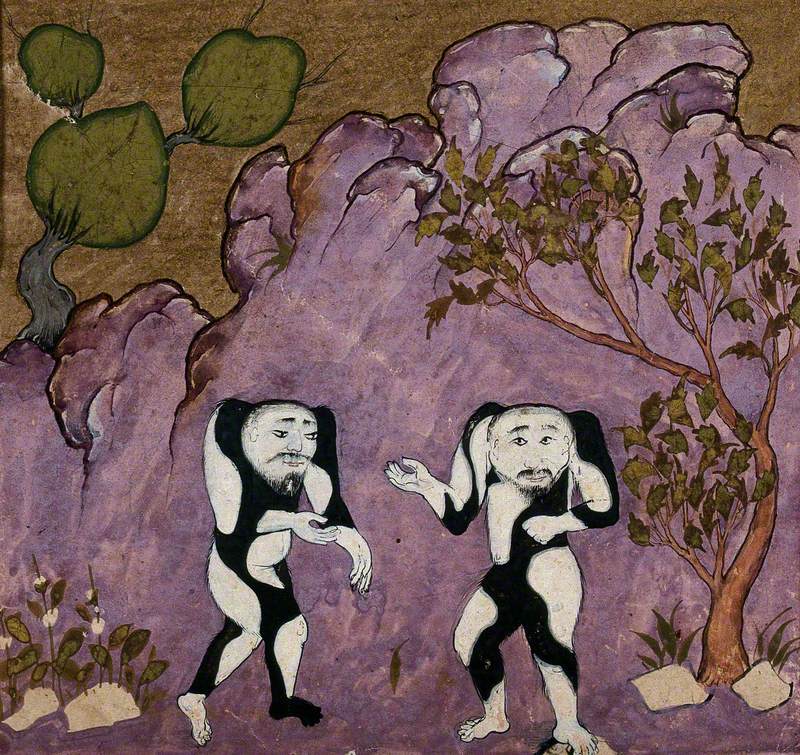

Another form of delusional love is narcissism, which has perhaps become more normalised in contemporary society. The notion of excessive self-love (in a non-physical sense...) was first discussed by the ancient

In the original Greek myth, the young, beautiful Narcissus fell in love with his own image reflected in a pool of water. Yet unable to consummate his love, Narcissus 'lay gazing enraptured into the pool, hour after hour', until he inevitably perished by drowning. In the story, Narcissus takes pleasure in rejecting others, when they too fall in love with his beauty. Echo, a mountain nymph, is left heartbroken, remaining only as an echo after Narcissus tells her bluntly he's just not into it (we've paraphrased from the Ancient Greek here).

Today, narcissism is considered a form of personality disorder, while paradoxically, others – for example, these readers of Elite Daily – argue that a healthy bout of narcissism can be a good thing.

The jury's still out on this one.

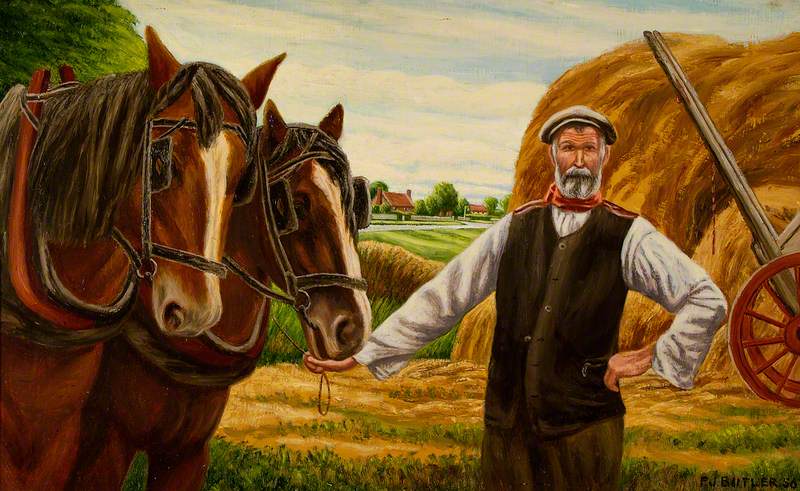

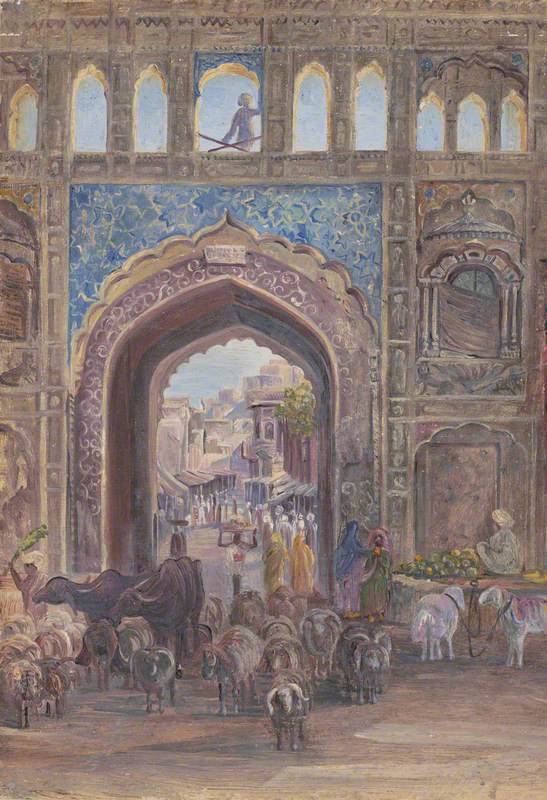

All is fair in love and war

This expression originates not from Shakespeare (as it is often mistaken), but from John Lyly's Euphues (c.1578). In short, it means that nothing is off limits when it comes to love and war – anything becomes acceptable on the battlefield. And, as Pat Benatar once sagely pointed out, love is indeed a battlefield.

This idea held some sway before the 1980s. Take, for example, the story of Antiochus I, a young Hellenic prince who falls madly in love with his stepmother Stratonice (awkward). The young prince is so desperately in love with his father's young wife that he falls seriously ill. Scenes of the Greek physician Erasistratus taking his pulse and diagnosing him with 'lovesickness' have been portrayed by artists for over the past 2,000 years, with some of the most famous depictions by Bellucci, Benjamin West, Guillemot, Ingres and Jacques–Louis David.

Image credit: The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology

The Marriage of Antiochus and Stratonice early 1490s

Bartolomeo Montagna (c.1450–1523)

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and ArchaeologySurprisingly, this story has a happy ending. Upon learning that his son was close to death because of lovesickness, Seleucus, King of Syria, allowed Antiochus to marry his wife.

We can only speculate what their family dinners were like afterwards... Please pass the salt?

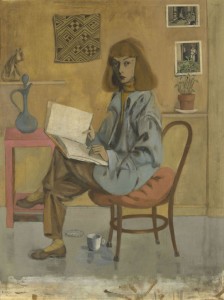

The course of true love never did run

Here is another Shakespearean proverb which is still used today, originating from the popular comedy A Midsummer Night's Dream. The play also centred around Shakespeare's conviction that love and madness were inextricably linked – 'lovers and madmen have such seething brains, such shaping fantasies, that apprehend more than cool reason ever comprehends.' In short, don't try squeezing any rationality out of a lovesick fool.

Within this farcical romantic comedy, four Athenian lovers are manipulated by ethereal woodland fairies, poisoned by Cupid's arrow, and duped by the mischievous sprite Puck. After drinking a love potion, they all become terribly confused and fall in love with the first character they see upon waking.

Here, Henry Fuseli has depicted Queen Titania falling in love with Nick Bottom, whose head was turned into that of an ass (again, love is blind).

Unlike Shakespeare's most famous tragedy Romeo and Juliet, there is a happy ending to this one.

Love actually IS all around...

This one certainly isn't Shakespeare... and if you are offended by this quote from an (arguably) Brit Christmas classic, you will probably enjoy this Jezebel article.

To conclude, before this article makes you cynical about love, let's consider the many upsides.

Despite some of the less favourable symptoms that appear on the wide spectrum of lovesickness – nausea, alarming heart palpitations, distraction, profound and unrelenting sadness – one can argue that falling in love is also one of life's most worthwhile experiences, especially if (let's hope) it is reciprocated.

But on an entirely different note, the universally understood subject matter of love and romantic failure has given us some of the best and most celebrated novels, music, poems, paintings, plays and films. Moreover, sometimes romantic failure can be a blessing in disguise.

On that note, we will leave you with this disgustingly cringeworthy conclusion – if love is indeed a sickness, then it is endemic and utterly incurable.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK