'To make pots is an adventure to me, every new work is a new beginning. Indeed I shall never cease to be a pupil.'

Lucie Rie (1902–1995) was an Austrian-born British studio potter, known for her innovative and modern approach to ceramics. A figure who permanently altered the landscape of studio pottery, both in Britain and abroad, the latest exhibition at Kettle's Yard in Cambridge is dedicated to the artist.

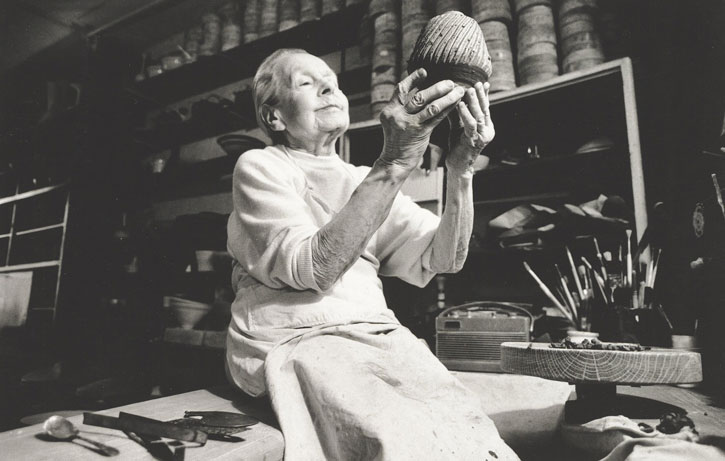

Lucie Rie working on the wheel, c.1952

Born 'Lucie Gomperz' in Vienna in 1902 to an affluent and secular Jewish family, Rie knew from an early age that she wanted to be an artist, initially a sculptor until she found her preference for ceramics. 'But when first I saw a pottery wheel, I decided at once to become a potter.'

She studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) at the age of 20, finally graduating in 1926. Associated with the Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop), Rie became exposed to the teachings of the Modernist architect and designer, Josef Hoffmann. Around the same time, she married her then-husband, Hans Rie, though the pair divorced in 1940.

In the 1930s, she established her own pottery studio in Vienna, where she experimented with brightly coloured ceramics and adopted an unorthodox raw-glazed style deploying rough surfaces and textures. Her work was well-received in Austria, and throughout the 1930s she won prestigious prizes for her ceramics, including a prize at the 1937 Paris International Exhibition.

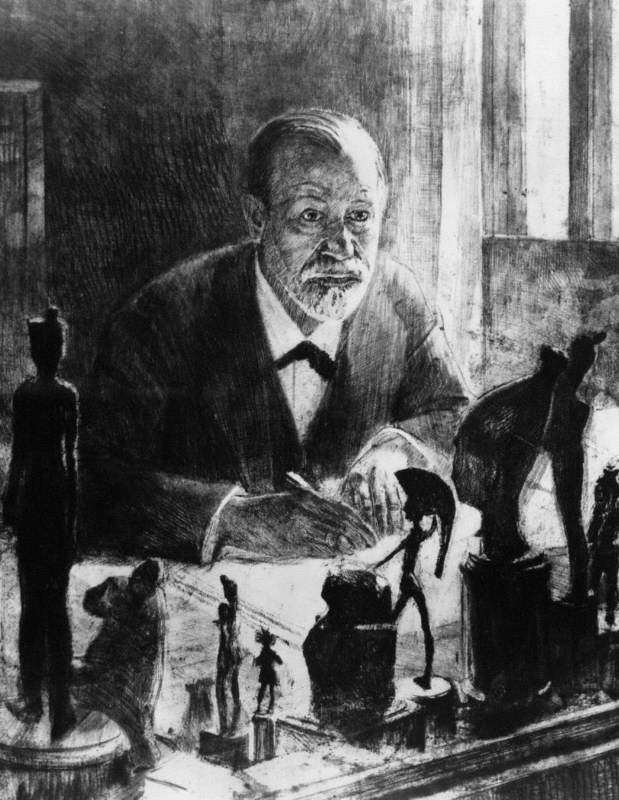

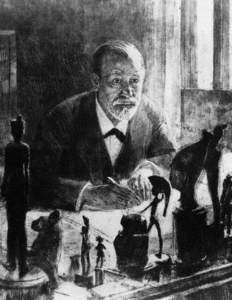

In March 1938, the annexation of Austria by Hitler's Germany, known as the 'Anschluss', came into effect, meaning Rie's career came to an abrupt halt. Open and widespread persecution of the Jews intensified in Austria immediately after the Anschluss. Jews were subjected to harassment, intimidation, and violence and were excluded from public life. In November 1938, the Nazis launched a massive pogrom against the Jews known as Kristallnacht, or the 'Night of Broken Glass.' Synagogues were burned, Jewish-owned shops and homes were destroyed, and Jewish men were rounded up and sent to concentration camps. By 1941, 130,000 Jews had left Vienna, including the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, who mixed in the same Viennese circles as Rie's family – her doctor father having worked closely with him.

Rie settled in London (carrying a few of her ceramics in her luggage) at the age of 36 in 1938. She resided at 18 Albion Mews, close to Hyde Park, which would become her home and studio until her death in 1995. Unknown to British audiences in the late 1930s, she was forced to set up an entirely new life and career for herself.

To integrate into the British art scene, she sought the advice of the esteemed potter Bernard Leach, who, inspired by Japanese pottery, advocated a rustic approach to ceramics – in simple and utilitarian forms. Although his ceramics diverged from Rie's refined, modernist style (he even described her pottery has having 'no humanity'), the pair became lifelong friends and creative confidants. While she did take inspiration from Leach's style – her pots becoming chunkier and more robust – she would later return to her elegant more refined style, in which thin lines typically accentuate the overall form of the ceramic.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, as a Jewish-Viennese woman in Britain, Rie was branded an 'enemy alien.' She lost her licence from the Board of Trade to make pots, so turned to the fashion industry. She survived by making accessories spared from rationing restrictions: ceramic buttons, jewellery and umbrella handles.

Buttons

1940s, earthenware by Lucie Rie (1902–1995)

Albion Mews became known as the 'Button Factory', and she hired a group of assistants, many of whom were also Jewish refugees. One of her creative protégés during this time was the German-born Hans Coper, who became an important ceramicist in his own right, as well as Rie's lifelong friend and collaborator.

Lucie Rie and Hans Coper

In 1940, Coper had been arrested as a refugee in England and sent by ship, along with other prisoners of war, to an internment camp in Canada. By registering with the Pioneer Corps, a unit that carried out construction and supply work for the British Army, Coper was finally able to leave the camp and return to England. At this point, in an attempt to find employment in London, he joined Rie's button workshop. Despite being twenty years his senior, the pair became close friends and creative collaborators. From the mid-1940s, the pair would often exhibit together.

The 1950s brought about significant change to British ceramics, witnessing innovative forms of pottery making. Such designs broke free from traditional constraints and experimented with new glazing and firing techniques, many of which Rie championed. Alongside Leach, then based in St Ives in Cornwall, Rie and Coper became leading proponents of this movement.

Bowl

1977, thrown porcelain with manganese glaze & sgraffito decoration by Lucie Rie (1902–1995)

Rie slowly established herself throughout the 1950s and 60s, becoming renowned for her distinctive tableware and one-off pieces, as well as her ceramic buttons. Stylistically, her ceramics stood out from other potters working in Britain in the post-war era, many of whom looked to medieval European and Asian traditions. In contrast, Rie's pieces were inspired by many sources – both historic and contemporary – and characterised by their refined shapes, delicate surfaces and vivid colours.

Coffee set

c.1960, stoneware by Lucie Rie (1902–1995), private collection

Both functional and decorative, modernist and abstract, she often incorporated subtle variations and irregularities that give them a unique and organic quality. She also became known for mastering a number of pottery techniques, including the 'flashing' glazing technique, in which the piece is fired in a kiln with a layer of powdered clay applied to the surface, creating subtler colour variations. By the late 1940s, she replaced earthenware ceramics with stoneware and porcelain, allowing her to make pots with thinner walls.

Around this time she also developed her signature technique known as 'sgraffito'. Derived from the Italian word 'sgraffire' meaning 'to scratch', the technique involves scratching a layer of coloured slip or glaze to reveal the contrasting texture of the underlying material. Many of her bowls and cups created in this era reveal delicate, thin scratched lines, as well as crosshatching.

Lucie Rie in her studio at Albion Mews, 1990s

In 1948, she became a naturalised British citizen. The following year, she held her first solo exhibition, at the Berkeley Galleries, London. Between 1958 and 1972 she taught at Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts, and continued to exhibit her work in British exhibitions.

Rie lived to the age of 93, though she stopped producing work after suffering from a series of strokes. Before her death she was awarded a damehood and also exhibited with Hans Coper at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Although she was forced out of her homeland, Rie's legacy lives on in Britain, a country where she found refuge and creative freedom. In 1951, Rie said: 'Here in England where I live and work for more than 12 years, I have found many friends many people who appreciate crafts... I believe that there is a wonderful spirit, a new beginning in this country and I am proud and happy to be a small part of it.'

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

'Lucie Rie: The Adventure of Pottery' is showing at Kettle's Yard, Cambridge until 25th June 2023