In 1730, a fortune teller by the name of Madame de Lebon received a visit from a little girl and her mother. Lebon went on to tell this nine-year-old girl that one day, she would reign over the heart of a king. From then on, this girl was known by the nickname Reinette ('Little Queen'). Reinette, whose real name was Jeanne Antoinette Poisson, would eventually be known to history as Madame de Pompadour, mistress to Louis XV.

Although her influence with the king was great – he retained her friendship and political counsel even after the end of their sexual relationship – Madame de Pompadour was also an important cultural force within the arts. She was both a sitter and a patron – she was a patron of many Enlightenment figures, including Voltaire – but also a creator.

Not content with commissioning and wearing jewellery, she created her own intaglios, installing a talented gem carver at Versailles and keeping a drilling machine in her apartments. She made a series of designs by the jewel engraver Guay into a portfolio of printed engravings, copies of which still exist in various museums, including the British Museum, the Met Museum, New York, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the Rothschild collection in the Musée du Louvre and a recently rediscovered copy that belonged to Pompadour herself at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. The engravings show everything from allegorical images depicting the personifications of Love and Friendship, to a charming etching of Pompadour's pet spaniel, Bébe, tail in the air.

As well as commissioning various works of art and architecture to adorn her Versailles apartments and various other pieces of property, Pompadour was herself the subject of numerous portraits by the likes of Jean-Marc Nattier, François Hubert Drouais, and François Boucher, some of which can be found on Art UK. The variety that can be seen in these portraits gives us a glimpse into the various ways that she sought to portray herself, and the assortment of roles she played throughout her long court career.

In a portrait from the early 1750s by a member of the French School, we see her as a pretty young girl, garlanded with flowers. This image contrasts with a portrait by Drouais, completed after Madame de Pompadour's death in 1764, but began in the last year or so of her life.

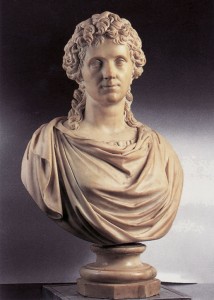

Madame de Pompadour at her Tambour Frame

1763-4

François Hubert Drouais (1727–1775)

Here, we see Pompadour in the role of a respectable woman of middle age, rather than the pretty, florally adorned youth of the French School portrait. Clad in a lace cap, she sits at her tambour frame, in the role of an artistic creator.

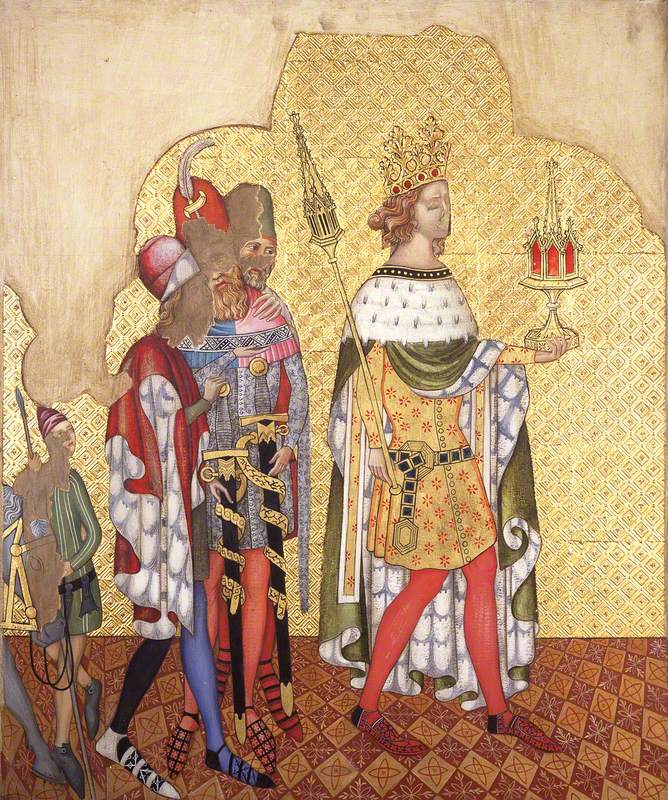

During the 1750s, Boucher created various images of Pompadour, all of which depict her in the same pose. Her body is positioned face-on, but her head faces off to the viewer's left, her gaze following that direction, giving us a semi-profile view of the marquis' face. The first shows her in a sumptuous panniered gown with frilled sleeves with matching ruffled choker, allowing us to see the grandeur of eighteenth-century court dress on full display.

Like the French School portrait, Reinette is adorned with flowers – but now, instead of a delicate garland around her neckline, a dramatic bunch blooms out of her bosom. This increase in the drama of her dress, accompanied by the sumptuousness of the Versailles apartments that form the background show off the rococo style that Madame de Pompadour loved in all areas of taste – decor, clothing and art.

Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764), Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson

c.1758

François Boucher (1703–1770) (attributed to)

Another Boucher depiction, this time a portrait, sees Pompadour (now closer up and seated) in a similarly elaborate ensemble, with the hat in her right hand of the initial sketch now replaced with a book. In front of her, is the marquis' writing desk, both objects reference Pompadour's intelligence and love of learning.

Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764), Mistress of Louis XV

1758

François Boucher (1703–1770)

The book, and its associated reflection of the marquis' intellect, is continued in the third Boucher portrait, which sees Reinette outside, surrounded by greenery, another common feature of her beloved rococo genre.

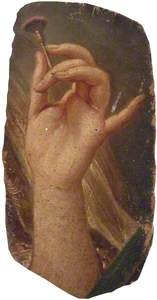

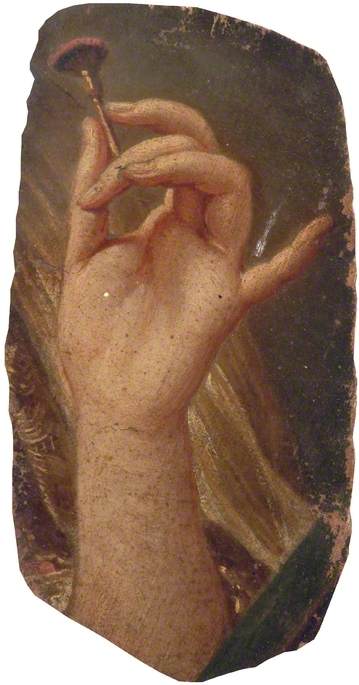

A painting, now at the Bowes Museum, shows an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century copy of a portion of another Boucher portrait.

The Hand of Madame de Pompadour

18th C–19th C

François Boucher (1703–1770) (copy after)

The Hand of Madame de Pompadour shows the marquis holding up her makeup brush, a section of a larger tondo image of Reinette applying her makeup at her dressing table.

Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour

1750 with later additions, oil on canvas by François Boucher (1703–1770)

The image is again decadently rococo. Reinette is clad in a splendid white gown, accented with large pink frills. Even the cape she wears to keep her makeup off of said dress matches, with the white cape she drapes around her shoulder crowned with a pink ribbon at her throat. On her wrist, she wears a pearl bracelet with a cameo of the king at its centre – and, God forbid it not also match her ribbons and rouge, it is, of course, a bright pink. This intimate gesture – the wearing of her lover on her arm – mimics the overall intimacy of the portrait. Here, we do not see her in the formality of her apartments or gardens, but are instead privy to the very process of her getting ready. The directness of her gaze (in contrast to the other Boucher portraits, this one sees Pompadour look at the viewer straight-on) only adds to this intimacy.

Sketch for a Portrait of Madame de Pompadour (1721–1764)

c.1750

François Boucher (1703–1770)

This mixture of grandness and familiarity, youth and maturity, frivolity and intellect seen throughout these various portraits gives us a fascinating look into the complexity of Pompadour's character and interests, and the ways she sought to portray this complexity to others. When one combines this rich portraiture with the legacy of her wider artistic patronage and own artistic endeavours, we can see that Madame Pompadour was truly a mistress of the arts, as well as mistress to a king.

Chloe Esslemont, freelance writer and co-founder of TabloidArtHistory