Maggi Hambling is a well-known and respected artist in Britain for her paintings and public sculptures, though her work is perhaps equally famous for its ability to divide public opinion. For over five decades Hambling has developed a distinctive vocabulary of painting and sculpture that has stood at the forefront of British visual art, with some of her most famous works being her portrait of the Nobel Prize-winning chemist Dorothy Hodgkin (1985), or sculptures such as A Conversation with Oscar Wilde (1998) or Scallop (2003) on Aldeburgh beach.

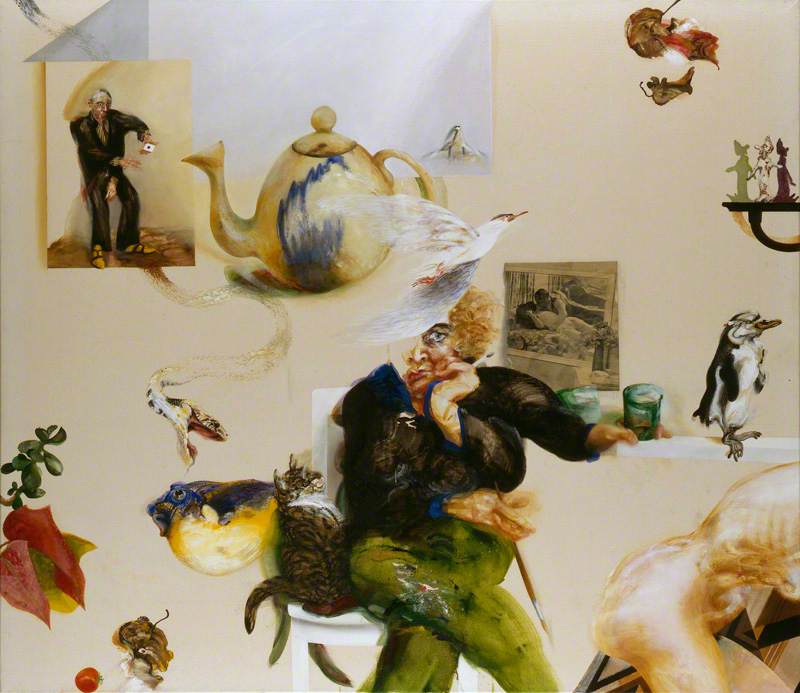

Based in Suffolk, Hambling is an eccentric, larger-than-life character who doesn't create art with the intention of pleasing an audience, or fitting into anyone else's ideas about what art should be. Her philosophy is that art, and in particular, painting, is in a constant state of 'happening': it must be allowed to come into fruition of its own accord, using the artist as a vehicle. Arguably, it's her unique ability to create strong reactions and stoke public debate – as seen in 2020 with her notorious A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft – that makes her an interesting artist who can reinvigorate the discipline.

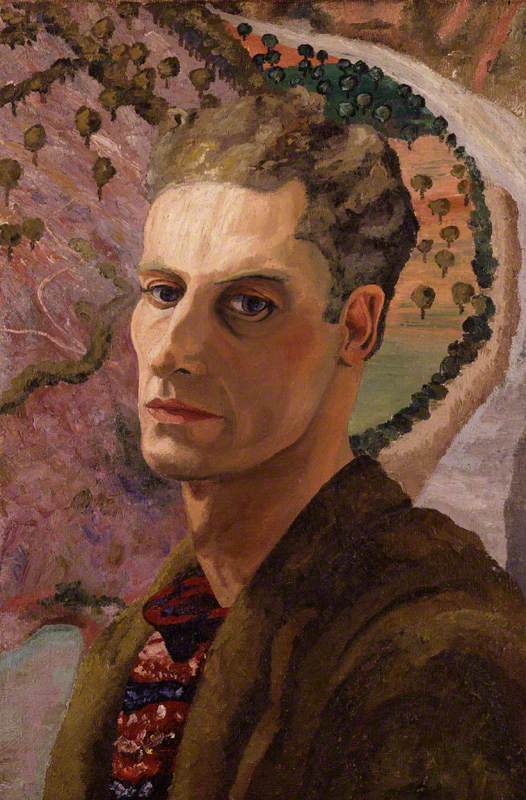

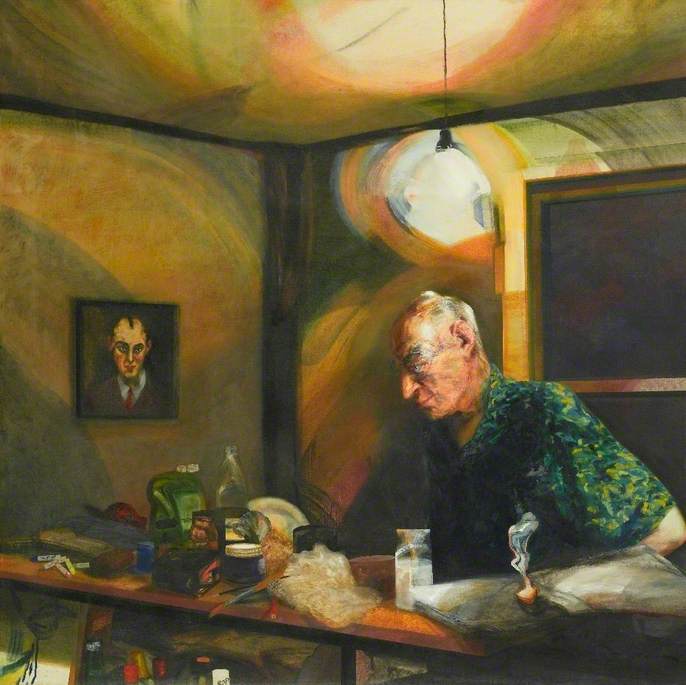

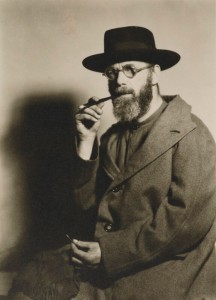

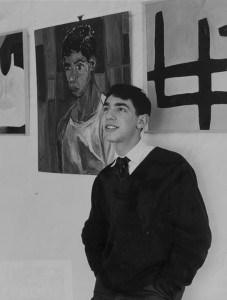

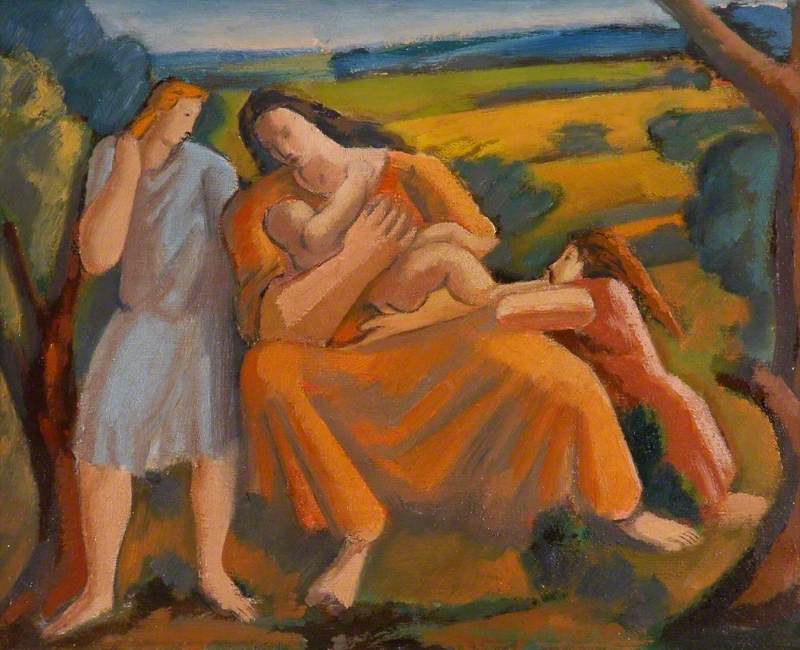

Born in Hadleigh, Suffolk, Hambling abandoned school halfway through her examinations to attend the East Anglian School of Art in Benton End to study art with Cedric Morris and Arthur Lett-Haines, the latter of whom became an important influence on her practice. Morris and Lett-Haines had first established the school in 1937, allowing it to flourish into a bohemian enclave of artists in the Suffolk countryside over the next few decades. Lucian Freud was welcomed as one of their first students, as well as figures such as people like John Nash, Frances Hodgkin and Bettina Shaw-Lawrence.

Speaking with the Financial Times in 2019, Hambling recalled: 'he [Lett-Haines] told me, aged 15, to make my work my best friend, which is how I have lived. Lett also said that no one could be an artist if they lacked imagination. He died in 1978 but remains my mentor. I have painted two portraits of him from memory recently.'

The artist continued her studies at the Ipswich School of Art in the early 1960s, before attending the Camberwell School of Art between 1964 and 1967. She also attended the Slade School between 1967 and 1969. She had her first exhibition in the early 1970s, and in 1980 she became the first artist-in-residence at The National Gallery. In 2010, she was appointed CBE for services to art.

A Conversation with Oscar Wilde

1998

Maggi Hambling

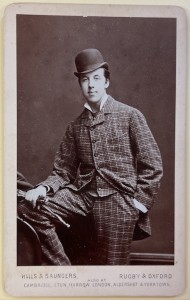

Hambling's first notable public sculpture, A Conversation with Oscar Wilde, is a memorial to the Irish writer, poet and playwright. The idea was first suggested by fans of his work in the 1980s, including the artist, filmmaker and LGBTQ+ activist Derek Jarman. Following Jarman's death due to AIDS-related complications in 1994, the committee 'A Statue for Oscar Wilde' led by Jeremy Isaacs and actors Judi Dench and Ian McKellen finally selected Hambling's design for the memorial. It was to be the first public monument dedicated to Wilde outside of Ireland, therefore the commission took on a significant cultural symbolism.

A Conversation with Oscar Wilde

1998, bronze and granite sculpture by Maggi Hambling (b.1945)

The sculpture reveals Wilde rising from his coffin, laughing and smoking. It was designed so that passers-by could touch and sit on it, like a public bench. 'You enter into a conversation with Wilde' Hambling explained, while revealing that she wanted to create a sculpture that would allow the viewer to be on the same level as the subject.

In an interview with frieze she said: 'Many people's idea of Wilde is that he was this extraordinary creature camping about the Café Royal, but he was very much a man of the people, too. He needed to be on our level.' Her unconventional and witty take on a memorial was inspired by a quote from Wilde's play Lady Windermere's Fan: 'we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.'

But the sculpture-cum-bench received ample amounts of scorn, with Tom Lubbock a the Independent describing it as a 'wilfully tacky, silly, Tussaudian tragedy.' Others found fault with its abstract and whimsical appearance, and the cigarette in Wilde's hand was stolen so many times, that the city stopped replacing it after a while (today the hand remains empty). The cigarette was perhaps also a reference to Hambling's own trademark; she refuses to be photographed without a cigarette in her hand, though she quit smoking years ago.

Nevertheless, the humour and unconventional nature of Hambling's memorial continues to attract countless pedestrians and tourists today, and it has become a cultural landmark of the Westminster area.

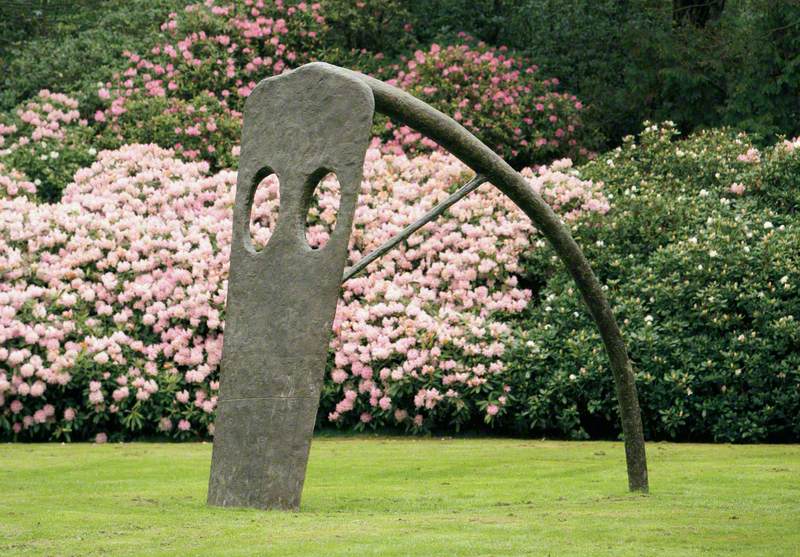

Scallop: A Conversation with the Sea

2003

Maggi Hambling, Sam and Dennis Pegg

Over the course of her career, Hambling has often credited the sea as her muse. Living close to the Suffolk coast, she regularly walks up and down the pebbled beaches listening to the sounds of the waves, which partly inspired her sculpture Scallop.

An ode to the composer Benjamin Britten, a fellow Suffolk resident until his death in 1976. The four-metre-high steel shell on Aldeburgh beach provoked a great deal of controversy – and vandalism – when it was unveiled to the public in November 2003. A project Hambling conceived of and paid for herself, the fact that it was not a public commission intensified the disapproval from some of the locals.

Formed of two halves of a broken shell and fabricated from steel, Scallop was designed to be both a sculpture and shelter for passers-by to sit inside as they contemplate and listen to the sounds of the sea. In the sculpture's upper edge a line of text is visible from Hambling's favourite Britten opera, Peter Grimes: 'I hear those voices that will not be drowned'.

Besides Britten, Hambling was inspired by the nostalgic memory of being a child and holding a shell to one's ear to hear the sea. The theme of an ongoing dialogue or conversation between art and audience, as well as the surrounding natural environment, informs and shapes the work.

In 2010, Hambling unveiled The Brixton Heron, a larger-than-life cut-out of a heron holding a fish in its beak and sitting on a weathervane. Commissioned by Lambeth Council, it is a moving, site-specific sculpture that engages with the surrounding community. In tended to lift the spirits of pedestrians or those travelling in eyesight of the sculpture, the artist chose to depict the heron on a weathervane to reflect the many directions from which the town's residents have come. 'Originally on this spot there was a Heronry. And then nearby a fish market. So a Heron fits the bill.' Hambling explained to Make it in Brixton.

A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft

2020

Maggi Hambling

Perhaps the most controversial of all Hambling's public sculptures, A Sculpture for Mary Wollstonecraft in Newington Green, London is situated outside the home of the eighteenth-century writer and proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft. Commissioned by the campaign 'Mary on the Green', the work would be the first public monument to Wollstonecraft in the world, and the completed silvered bronze sculpture was finally unveiled in November 2020.

To the surprise of many, the work presents an allegorical version of the real historical figure, one that was naked and emerging from indistinct organic forms. Wollstonecraft's famous quotation is inscribed on the sculpture's plinth: 'I do not wish women to have power over men but over themselves', taken from her 1792 work A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Numerous women criticised the sculpture, finding offence in the subject's minuscule size and lack of clothing. Others pointed out that her physique was idealised and unrealistic, perpetuating cultural pressures on women's bodies. Against the chorus of discontent, curator Eleanor Nairne wrote more positively about the work for the New York Times: 'The reactions to the work have focused on the nudity of this diminutive Everywoman. But might this also be understood as a metaphor for Wollstonecraft's vision of personal authenticity?'

In an interview with frieze, Hambling eventually gave her reaction to the reactions of her work. 'I was amazed by people's puritanical response to the tiny naked figure. They mistakenly thought it represented Wollstonecraft herself, but it's her spirit, she was a rebel, for goodness sake!'

What many misunderstand about Hambling is that she is not concerned with pandering to contemporary audiences, nor does she intend to be provocative for the sake of it. Her art is a direct reflection of her own creative process and temperament: she's an authentic individualist who doesn't follow the crowds.

To an extent, one could argue that Hambling's approach is quite insular, in the sense that she's working from her own intuition and research, rather than looking outwards and avidly ascribing to current cultural conversations. But this unhindered and uninhibited way of working is also her strength. She once said: 'When one is really painting, the painting has nothing to do with it. The painting is painting itself.' Whether the same philosophy can be directly applied to her public sculpture is up for discussion, though it is clear that above all she wants her audience to enter into a conversation with her works, all of which refer to the unique identity and history of their surroundings.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK