For many women artists who lived through the Second World War, as Mary Fedden (1915–2012) did, the conflict meant a hiatus in their careers. Far fewer women than men saw their work supported by regular commissions from the War Artists Advisory Committee, and many, like Fedden, volunteered for war work. Fedden worked in the Land Army, and then for the Women's Voluntary Service, before being called up to serve as a driver in the NAAFI in 1944.

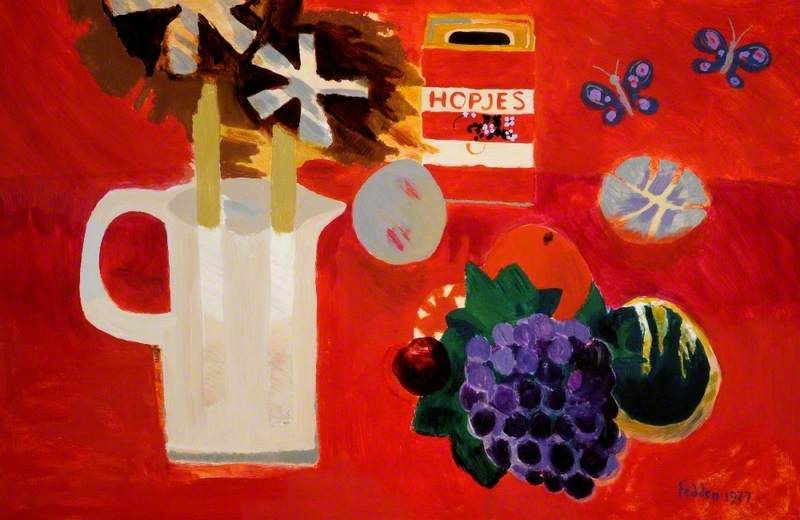

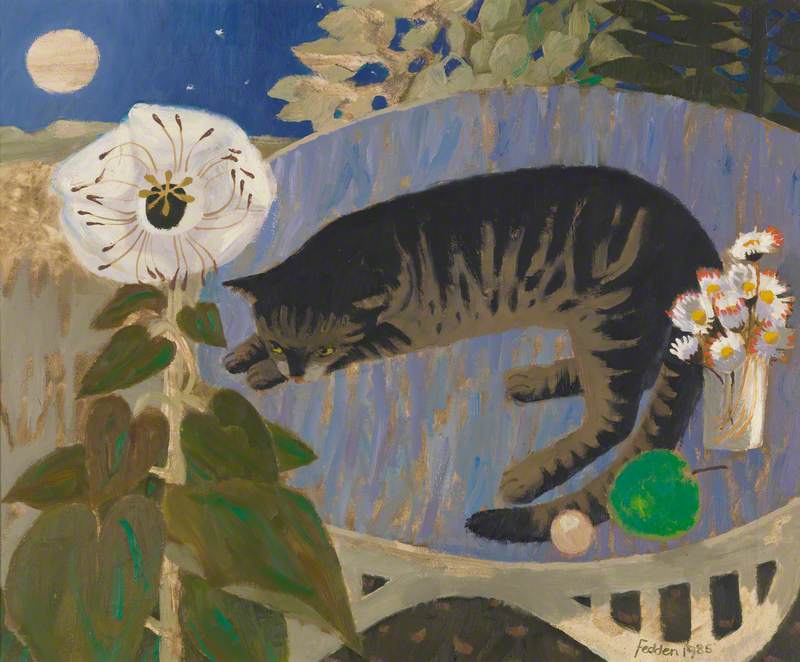

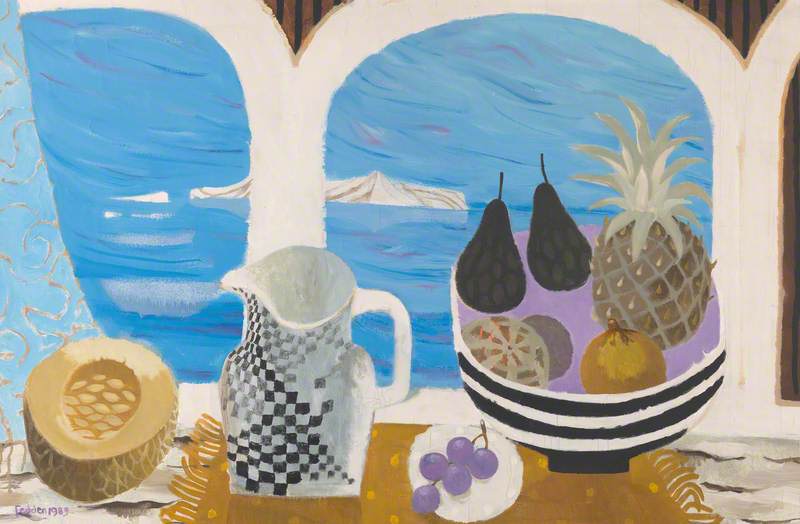

The privations of war restricted her painting life and cut her off from great art – The National Gallery, for example, sent its collection to safety, and travelling to Europe to see paintings was impossible. This would be a challenge for any young artist, and was especially so when there were none of the technological advantages we have today, of accurate reproductions and virtual museum tours. After the war, Fedden seems to have been determined to make up for lost time, and to capture in her paintings the pleasures of life previously taken for granted, but denied to so many – beauty and colour, foreign fruits, abundant flowers and distant landscapes.

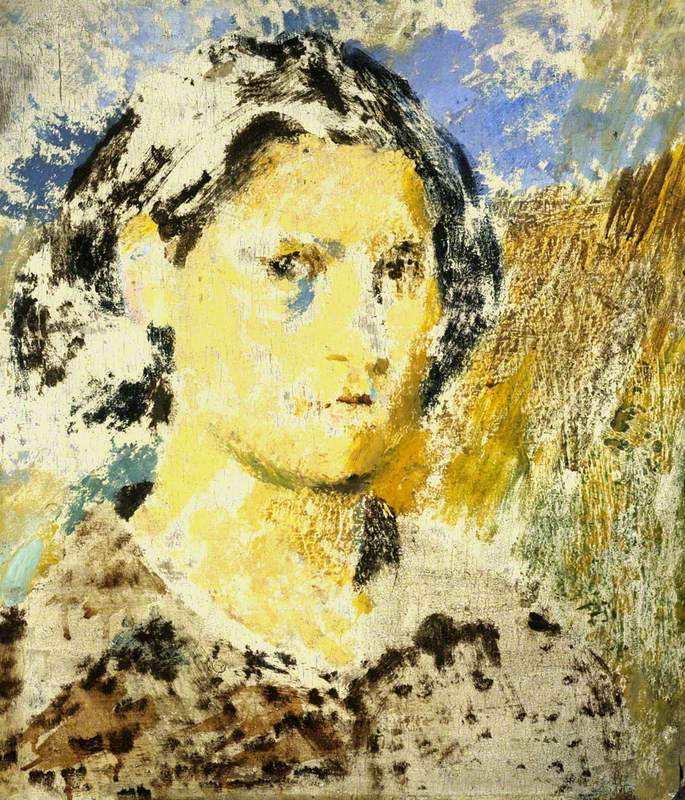

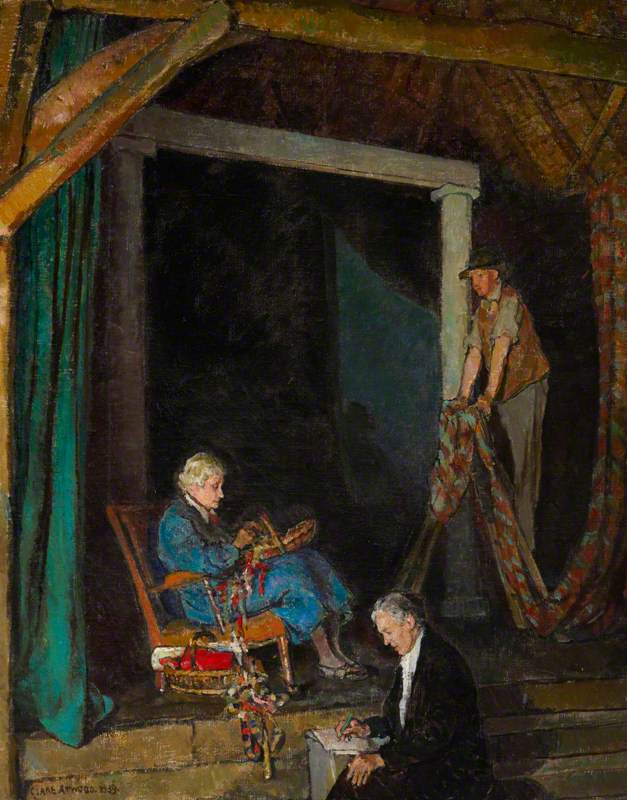

Fedden had moved from her home city, Bristol, to train at the Slade at the age of 16, and its influence can be seen in an early painting, The Prophecies of Isaiah.

It is reminiscent of Slade school competitions, when students were asked to create work on biblical themes, and of her precursors there such as Stanley Spencer (1891–1959).

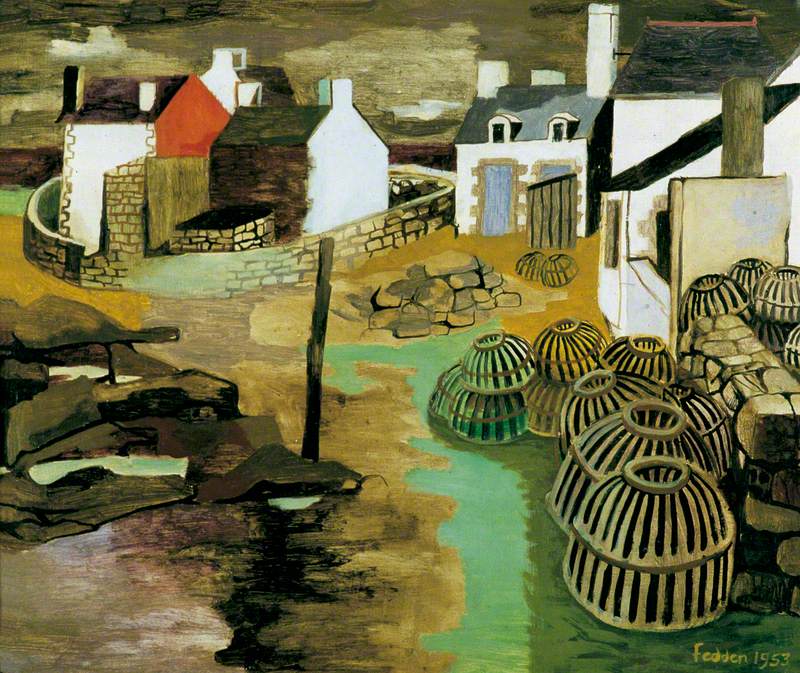

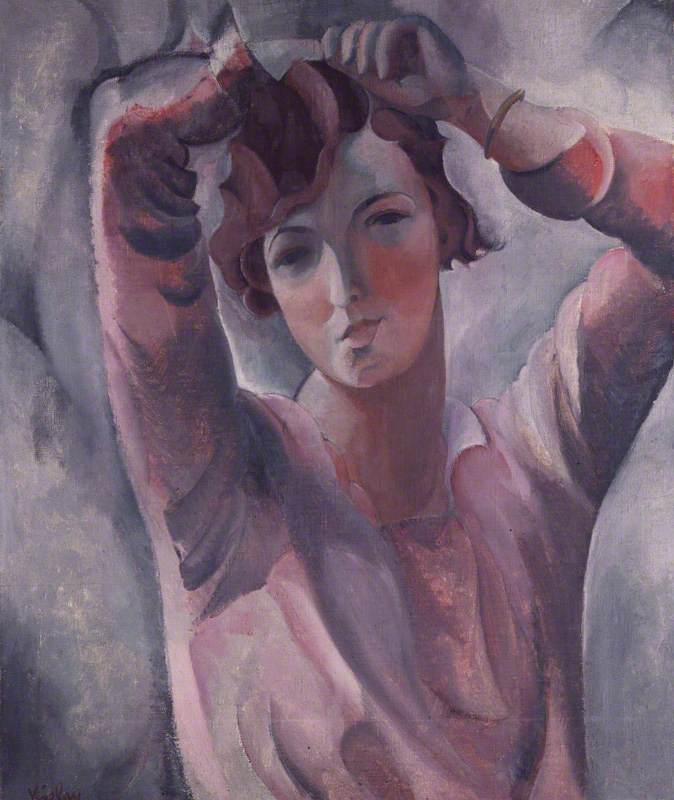

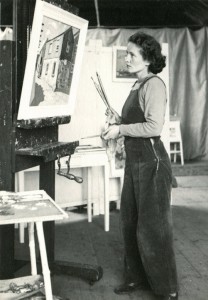

But it was a particular Slade tutor, Vladimir Polunin (1880–1957), who was to help form Fedden's painting more than any other. The theatre designer had worked with Diaghilev's Ballets Russes and with Pablo Picasso, and Fedden's opulent palette, strong even when it was subtle, harks back to the sumptuous colours of the ballet's costumes and sets. Like Polunin, Fedden worked for a time as a stage painter, designing for Sadlers Wells and the Arts Theatre, but her ambition was to be a fine artist, and from 1946 she began to devote herself to easel painting.

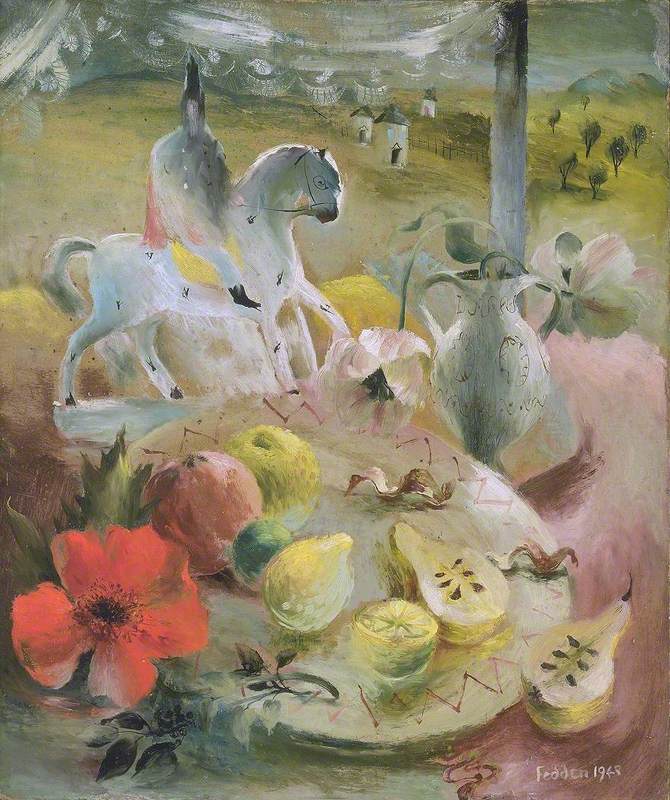

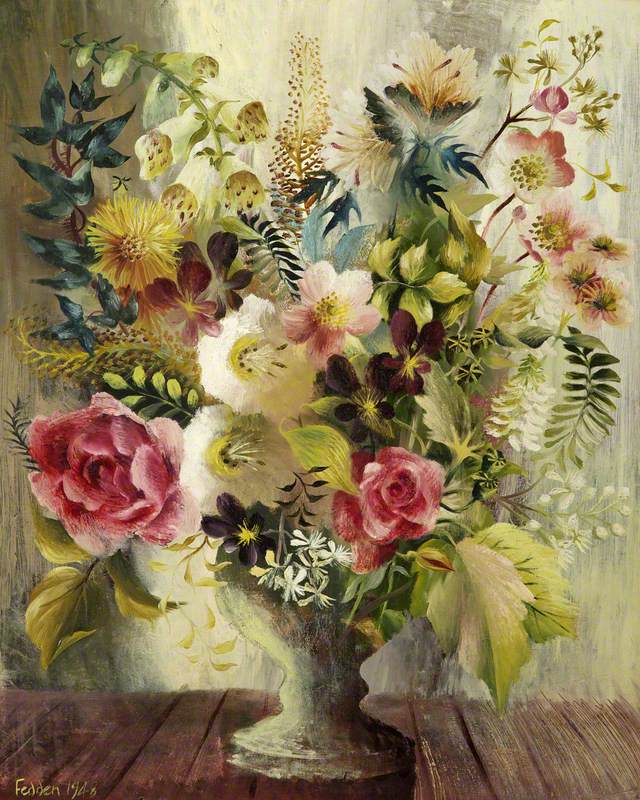

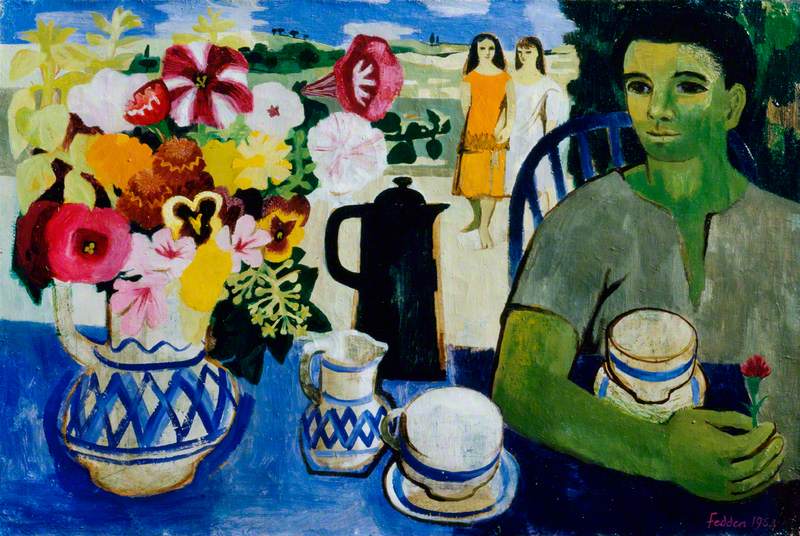

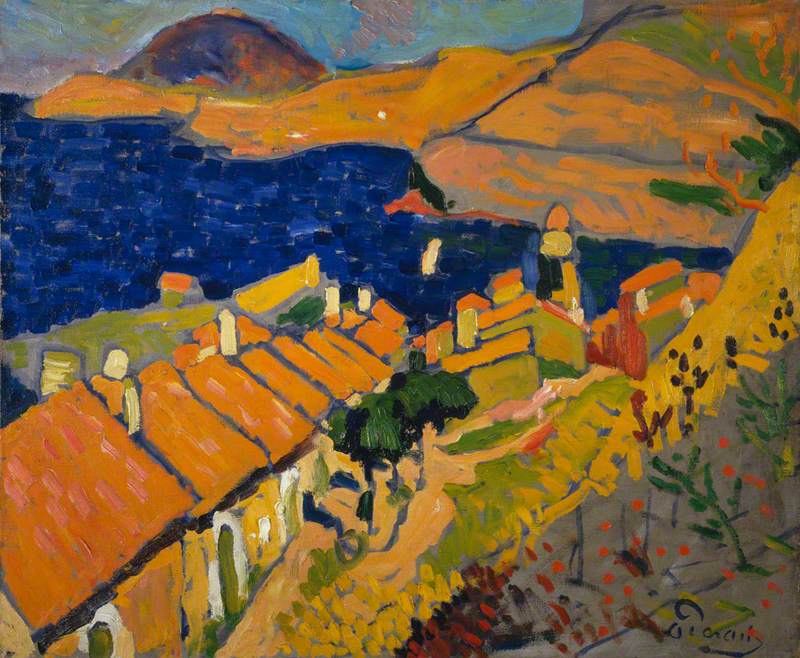

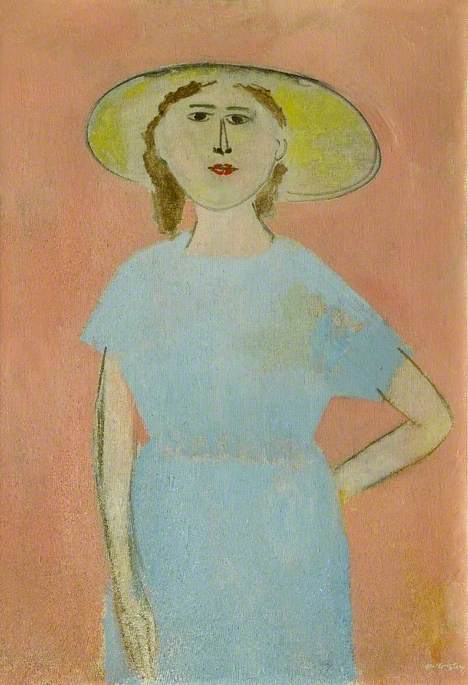

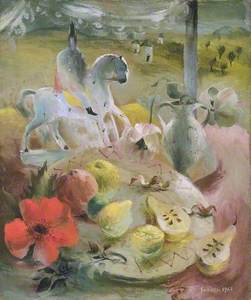

The following year Fedden had her first solo exhibition, at the Mansard Gallery, Heal's Department Store, where she showed still-life and flower paintings. Her Sicilian Flowers, painted during this period, gives an idea of her art at this time.

Once travel was allowed again, Fedden made full use of the opportunity, visiting several continents over her lifetime, and there is a reference to her journeys in the title and subject of this painting. The exquisite colour which, though not yet as vivid as in later years, gives a foretaste of what was to come.

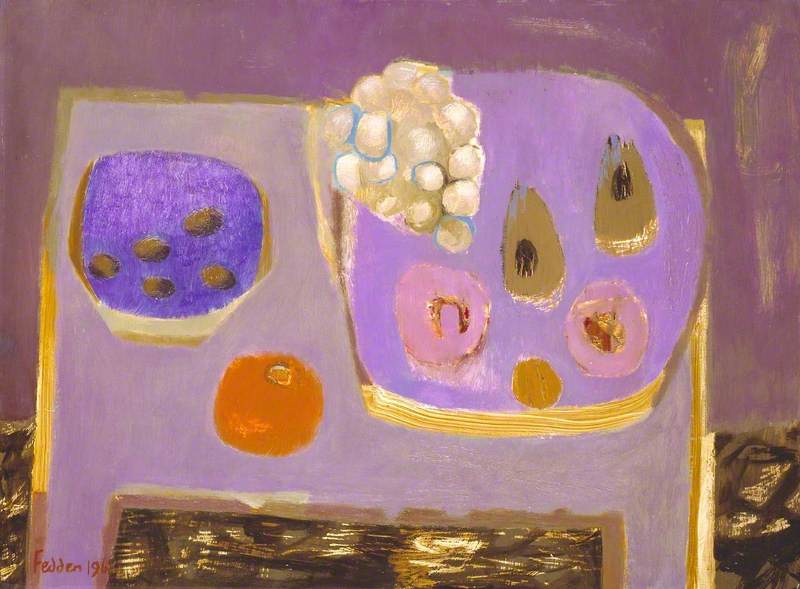

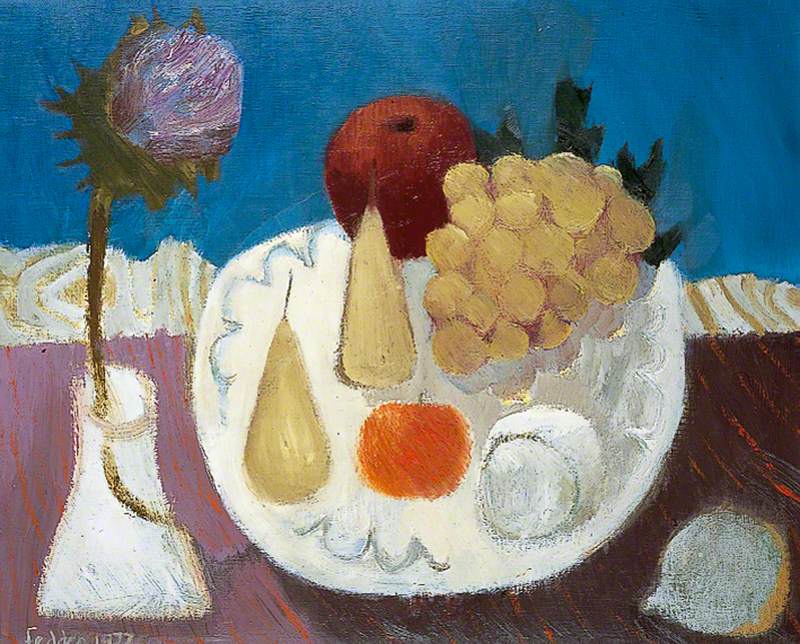

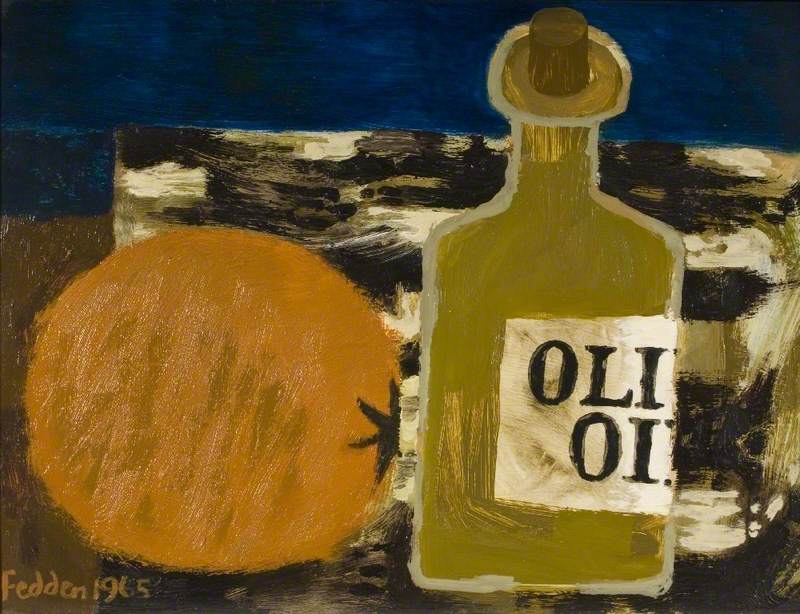

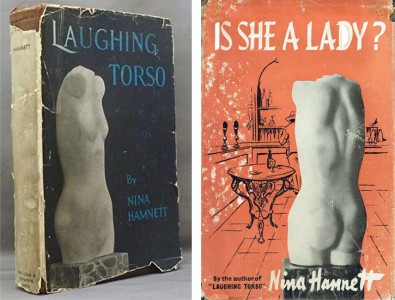

We can imagine, perhaps, during the current pandemic crisis and ensuing lockdown, a little of what it was like for those in mid-twentieth century Britain to emerge from a period of national isolation, privation and loss and find the world opening up once more. The later 1940s and 1950s was an era in which there was a hunger for the experiences that had been scarce, if not impossible, during the war years. Elizabeth David's A Book of Mediterranean Food, published in 1950 with a cover by John Minton (1917–1957), a friend of Fedden’s, contained a still life of tables laid with food – melons, grapes, lemons, garlic – and wine, against the backdrop of a landscape of blue sky and sea.

There was a desire for the end of austerity, to build a new world out of the ashes of the old that was epitomised in the Festival of Britain held on the South Bank of the Thames in 1951. Fedden was one of a number of artists commissioned to make work for the festival, and painted a mural (since destroyed) about children's lives and programmes for a pavilion celebrating one of the newest technologies then available: television.

In the same year she married fellow artist Julian Trevelyan (1910–1988), whom she had met at the Slade. Their partnership lasted until his death in 1988, and led to collaborative work and mutual influence over nearly 40 years.

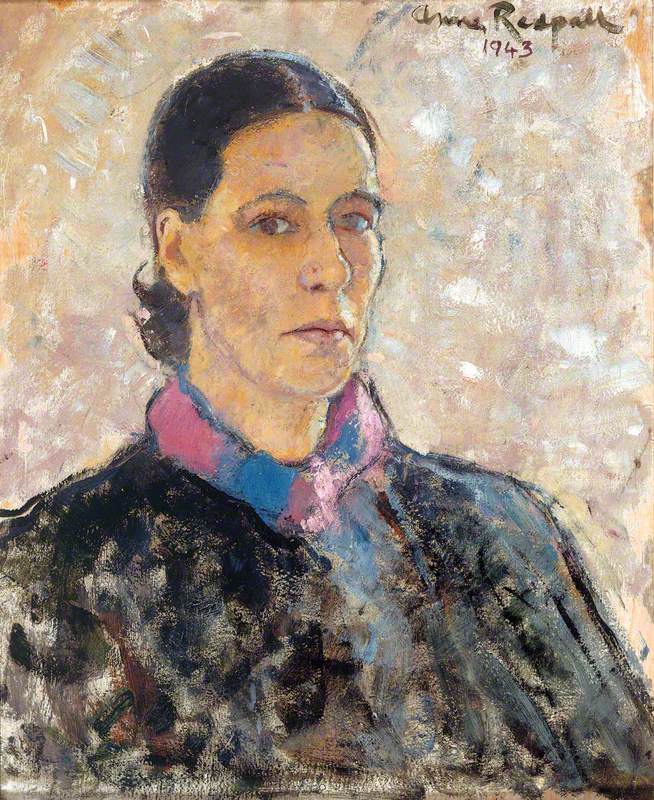

Fedden would use her husband's rejected etchings as source material for her collages, and credited their further development to his knowledge of French modernists such as Matisse, Picasso and Braque, and their compositional inventiveness with the most quotidian objects: a bottle, a newspaper, a bowl of fruit. She was already an admirer of Anne Redpath (1895–1965), Winifred Nicolson (1893–1981) and Ben Nicholson (1894–1982).

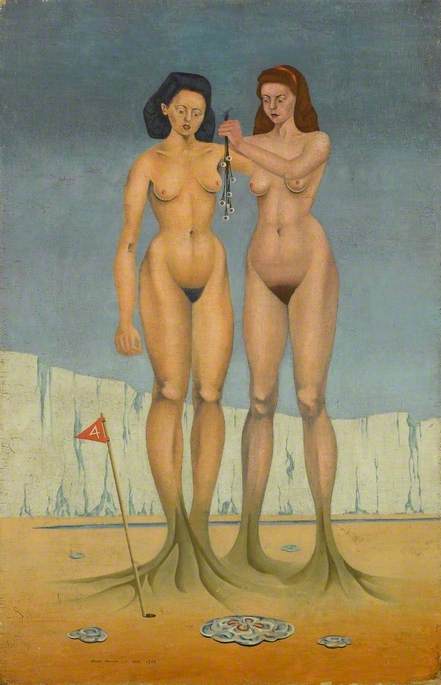

Interviewed for the National Life Story Collection in 1991, Fedden described how her travels with Julian Trevelyan allowed him to develop his passion for painting reality that he had kept something of a secret during his earlier, pre-war, surrealist period. They were jointly commissioned to make a mural for Charing Cross Hospital. Their oil painting, Old Hammersmith, of 1980, marries the subject of an old riverside London that was fast disappearing with a modernist sensibility evident in the panorama of cut-off figures in an urban landscape, with advertisements (for tea and Bovril) and Matisse-like simplification of birds and clouds.

The couple lived and worked at Durham Wharf, Hammersmith, and their art collection, which included work by Picasso and Henry Moore (1898–1986), was auctioned in 2016 to fund development of their building into a not-for-profit centre for artists, who are too often priced out of studios in the capital.

Fedden also left a legacy of success to inspire future women artists. She was the first-ever female painting tutor at the Royal College of Art, where she taught David Hockney (b.1937), Allen Jones (b.1937) and Frank Bowling (b.1934) – no small feat at a time when talented women (such as Pauline Boty, 1938–1966) were discouraged from even applying to be students of painting.

Mary Fedden (1915–2012), President of the Royal West of England Academy (1984–1988)

Sylvia Manasseh

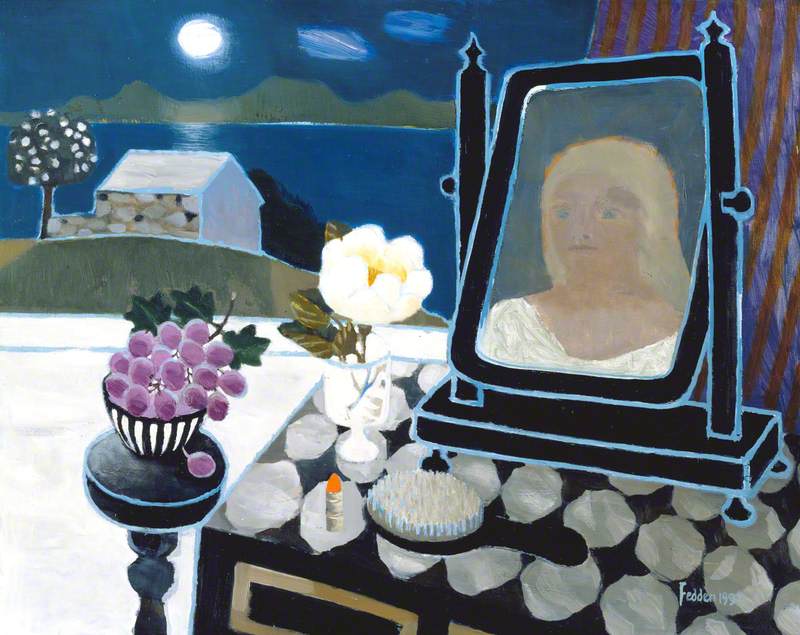

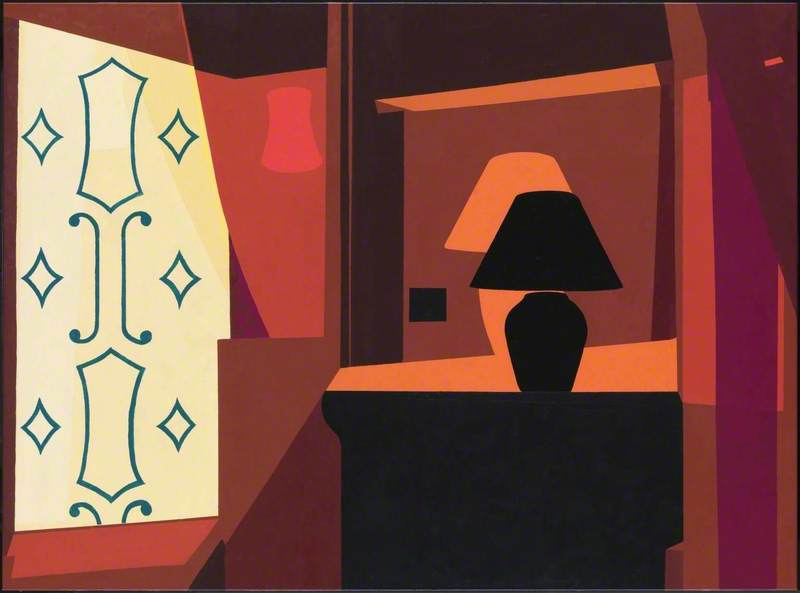

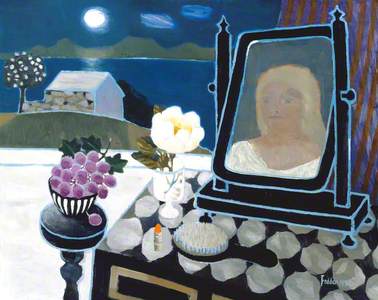

Fedden also became President of the Royal West of England Academy, Bristol, in the mid-1980s, and was elected to the Royal Academy in 1992. The painting she gave to the Academy on becoming an RA, Reflection, is of an interior.

A woman sits before a mirror but her gaze is not trained upon herself but drawn out through an open window, over the water and into the distance.

Alicia Foster, curator