We might think of the nineteenth-century art world as dominated by men whose ideological and aesthetic preferences influenced public collections, the decoration of churches and civic buildings across the country and conclude that there was little room for women artists to thrive. However, from the second half of the nineteenth century, opportunities for women to undergo formal artistic training increased.

Whilst the art world remained dominated by men, women gradually became a more consistent presence in art academies, studios and galleries. Increased access to art education, and the burgeoning Arts and Crafts movement opened up new opportunities for women artists, who had an increasing presence in the design and manufacturing of stained glass from the late nineteenth century onwards.

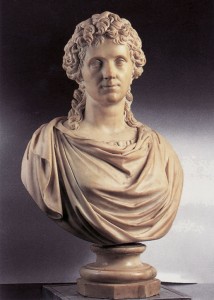

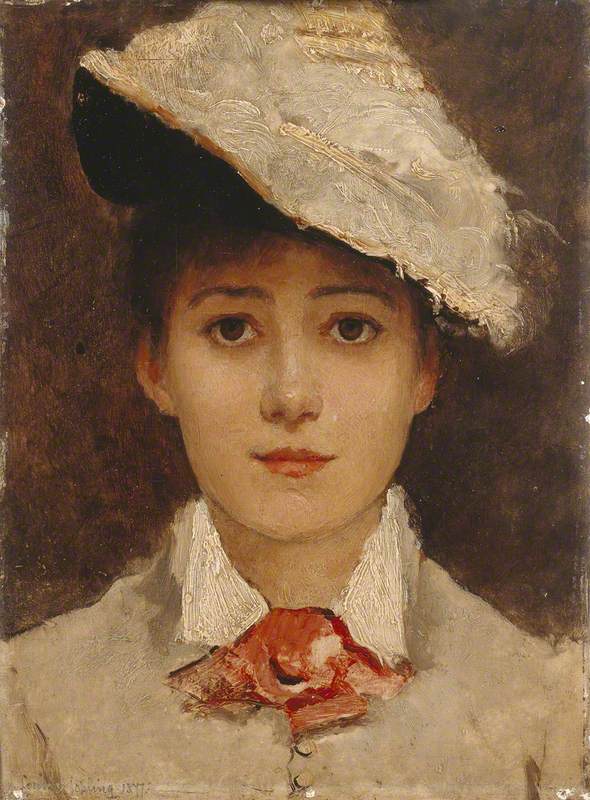

Mary Lowndes

c.1890s, platinum print by Arthur James Langton (1855–after 1919)

One of the first and most significant of these was Mary Lowndes (1856–1929), a pioneering artist whose work can be seen in churches and civic buildings across the country.

Lowndes trained at the Slade School of Fine Art in London (founded in 1871), one of the first fine art educational settings that gave both male and female students parallel access to the life model. Following her period at the Slade, from 1883 to 1886, Lowndes became an assistant to prominent stained glass designer Henry Holiday (1839–1927), where she assisted with cartooning windows and arranging life models.

The first of Lowndes' own designs for stained glass were made at Powell & Sons of Whitefriars between 1888 and 1892. By the 1890s, Lowndes was working independently from her own studio in Chelsea but, since she did not have access to kiln facilities, travelled across the city to Britten and Gilsen's studio in Southwark to select the glass, paint and supervise the firing and glazing.

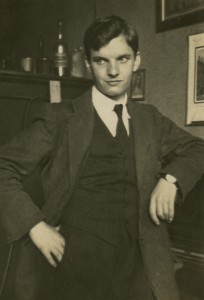

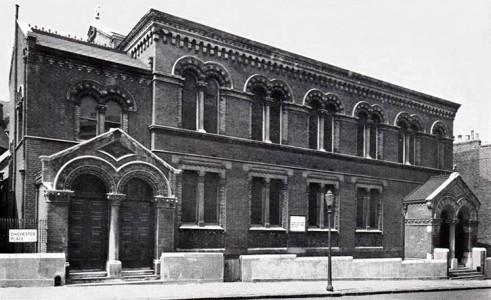

The Glass House building in Fulham, 2014

The need for a studio – that would allow her to work independently and have access to the facilities she required – led her to go into business with Alfred Drury, former foreman at Britten and Gilsen's studio, in 1897. Together they founded the eponymous 'Lowndes and Drury' studio in Chelsea. The studio flourished and in 1906 they moved to custom-built premises in Fulham, which later became known as 'The Glass House'.

The Glass House offered studio space and shared kiln and workshop facilities to independent artists, and quickly became a hub for English Arts and Crafts stained-glass design for leading artists of the day, including many women who were unable to take up positions within traditional studios.

This modern approach to the studio is not unlike the shared workspaces many businesses and artists utilise today. At the time it allowed these artists to follow the principles of the Arts and Crafts ideal and to oversee the design, cutting, painting and leading of their own windows. This was a more independent creative process than that experienced by artists working for larger commercial firms where the process of making a stained glass window was divided and many hands were involved in the production of a single window. The Glass House was an important centre of twentieth-century British stained glass production for more than 80 years, closing in 1993.

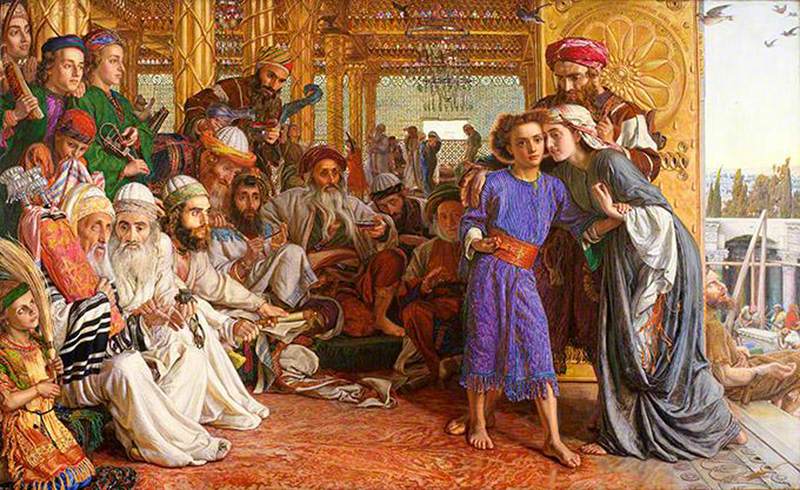

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple

(copy after William Holman Hunt) 1910

Mary Lowndes, Lowndes and Drury

Mary Lowndes' stained glass window depicting The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, now in the collection of The Stained Glass Museum, was made in 1910 at The Glass House. It is a close copy in glass of the famous Pre-Raphaelite painting of the same name, painted by William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) between 1854 and 1860. The scene illustrates a passage from the Gospel of Luke and depicts the moment at which Mary and Joseph find their son Jesus debating the interpretation of the scriptures with learned rabbis in the temple after looking for him for three days.

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple

1854–1860

William Holman Hunt (1827–1910)

Hunt sought to create a religious image that combined ethnographical accuracy with Biblical symbolism and travelled to the Middle East to conduct research before creating his painting. He is known to have used local people in Jerusalem as models for his paintings and studied ancient Jewish customs and rituals.

Hunt was one of the founders of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and his religious paintings made him famous. The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple was a popular image in the Victorian period. It was exhibited widely during touring exhibitions where visitors could buy a brochure describing the image and subscribe to an engraved reproduction.

By the time Lowndes was working on this memorial window, Holman Hunt's painting was in the collection of the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (where it was presented in 1896) and was widely known. Lowndes translated this well-known painting into glass, successfully combining key elements of the original design whilst meeting the requirements of the space and the design necessities of creating a stained glass window. A simplified composition was created by removing some of the figures and simplifying background details and perspective. This allowed the design to be successfully reproduced in glass, and for the window to emit more light.

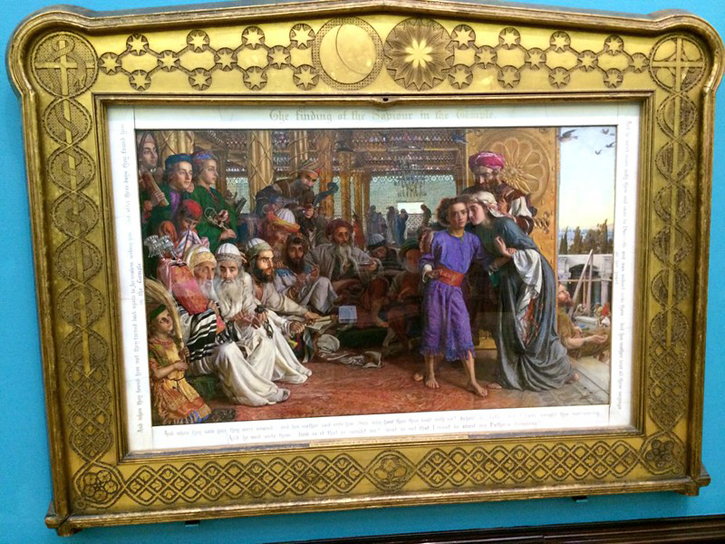

'The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple', framed, in Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

1854–1860, oil on canvas by William Holman Hunt (1827–1910)

Hunt's painting was displayed in an elaborate gold frame with painted inscriptions. Lowndes mimicked this effect in her window by creating a wide border of plain glass surrounded by laurel wreaths to frame the figurative scene.

A contemporary article praised the general appearance of the window, noting that 'Exception might possibly be taken to the border – a broad band of almost unrelieved white that scarcely harmonises with the old glass – but otherwise Miss Lowndes has been quite successful in her efforts, in the figure work conspicuously so; and in the faces of the chief priests and elders, so varying in their pose and expression, the feeling of intense eagerness and surprised wonder is strikingly apparent.'

All Saint's Church, now the Lincoln College library, in Oxford

Lowndes' window depicting The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple was originally made for a south-facing window of All Saints' Church, Oxford. Following the church's closure in 1971, the building was repurposed as a library for Lincoln College, part of the University of Oxford. This window was one of two stained glass windows that were removed and donated to the museum's collection in 1975 when the Grade I listed church was converted.

Newspaper reports state the window was commissioned 'In memory of Geoffrey Payne, who died in October 1908 and Mr Rupert Septimus Payne, died August 1910.' The men were aged just 23 and 19 respectively and both were sons of George and Octavia Payne of Oxford. The family ran a silversmith and jewellers business, Payne & Son, still trading today in Oxford.

Stained glass work by Mary Lowndes in St Peter & St Paul's Church, Shropham

It is not uncommon for subjects and compositions first seen in oil paintings to be replicated in stained glass, and many Pre-Raphaelite paintings were popular images for stained glass windows. But the horizontal format of Lowndes' large stained glass window is unusual. No other copies of paintings on glass made by Lowndes are known. In many ways, it is very untypical of her work. But this makes it more interesting as an example of her work and also in demonstrating the widespread influence of Pre-Raphaelite art in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

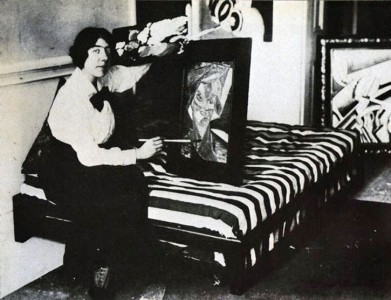

Alongside her commissions for buildings across the country and her commitments to the studio she had created, Lowndes also paved the way for many women artists through her feminist activism, as both a committee member of the feminist magazine The Englishwoman's Review and her active role in the women's suffrage movement from the 1890s. As Chair of The Artists' Suffrage League, founded in 1907, Lowndes assisted the Suffrage movement by creating posters, postcards, banners and Christmas cards to raise the profile of the cause.

We’re celebrating #StainedGlass artists who supported #Vote100 Mary Lowndes used her talents as an Arts & Crafts glass artist & her commitment to Women’s Suffrage to create many banners & posters for them. In 1907 she also founded the Artists’ Suffrage League #Suffragette100 pic.twitter.com/G5Fp4iPkX4

— Stained Glass Museum (@stainedglassmus) February 12, 2018

Lowndes never married, remaining an independent woman of independent means. She lived with her lifelong companion, fellow Artist's Suffrage League member and League secretary, Barbara Forbes.

Jasmine Allen, Director and Curator of The Stained Glass Museum

.jpg)