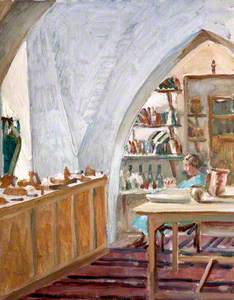

A painting at the famous house of a famous woman shows a scene different from the house's own beautiful views over the Devon coast. The windows of Greenway, the house its owner called 'the loveliest place in the world', look out to green lawns and wooded banks sloping down to the River Dart. The painting shows the hot dusty New Street in Baghdad, crowded with transport including a donkey, a bicycle, and a carriage, from which two smartly dressed western women look incuriously at the men lying in the dust by the ice cream vendor – one man peacefully asleep with his cloak rolled under his head, one perhaps in a sorrier state judging by the shocked stance of a bystander.

The painting was neatly signed Mary W. Parker, and there was certainly no mystery about the identity of the owner – Agatha Christie, one of the most famous and best-selling authors in the world. Her children passed the house and contents to the National Trust after her death in 1976.

However, the connection between the two women, and how the exotic painting came to hang on the walls of a cool white English country mansion, took the combined excavation talents of the Art Detectives – not helped by the fact that the artist later changed her signature to Mary Parker Smith, and finally Mary Smith – with the redoubtable Osmund Bullock and Pieter van der Merwe leading the hunt. The original query came from Professor Ihsan Fethi, an architect and art historian from Baghdad, who was intrigued by the painting, but said he could hardly find any information about the artist.

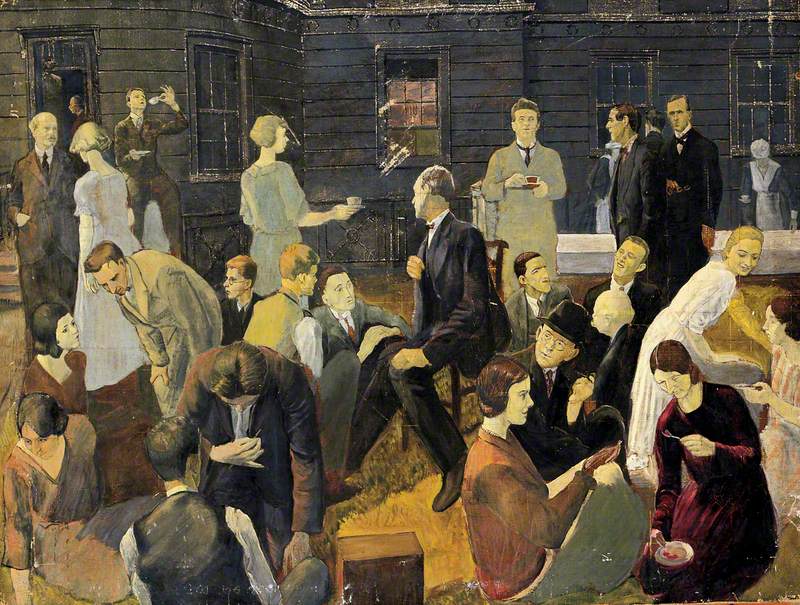

In 1930, the date of the painting, both women would have been very well known to the archaeological community in Baghdad, less as artist and author than as Mrs Smith and Mrs Mallowan, wives of the distinguished archaeologists Sidney Smith and Max Mallowan.

Mary Winifred Smith

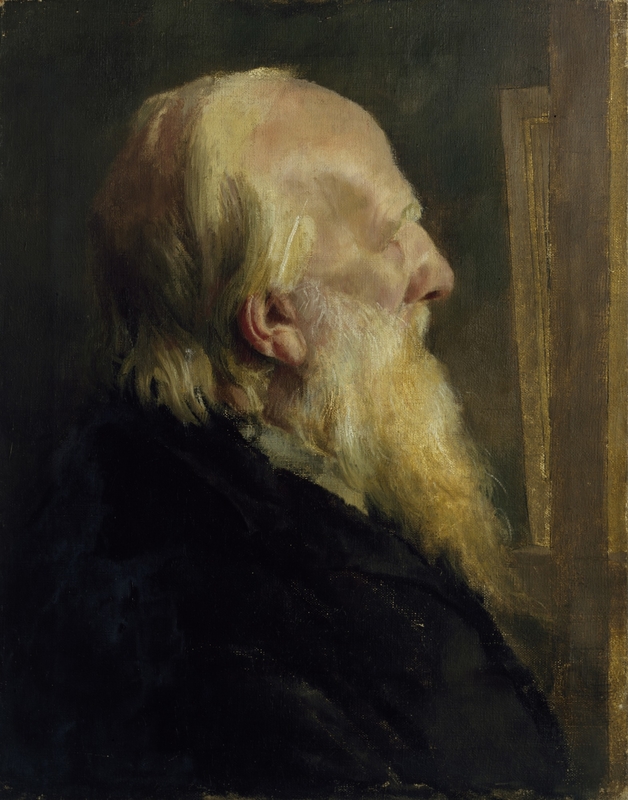

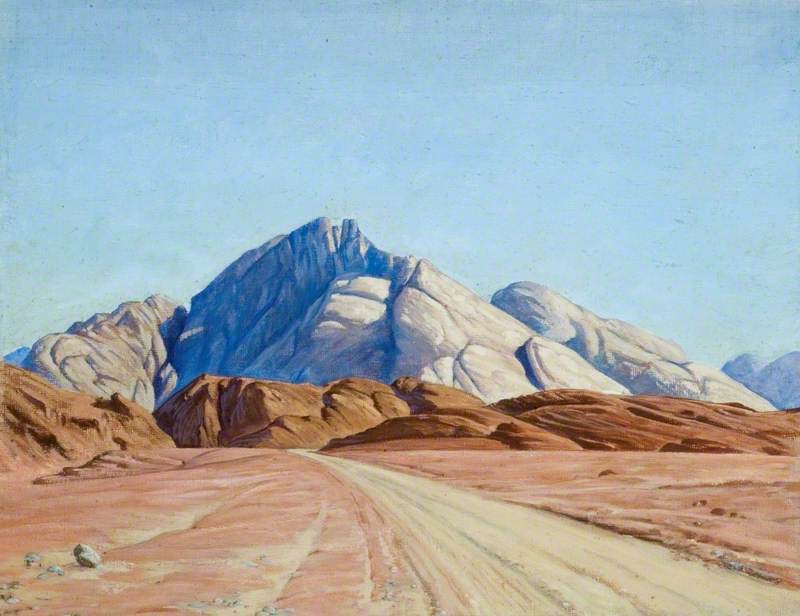

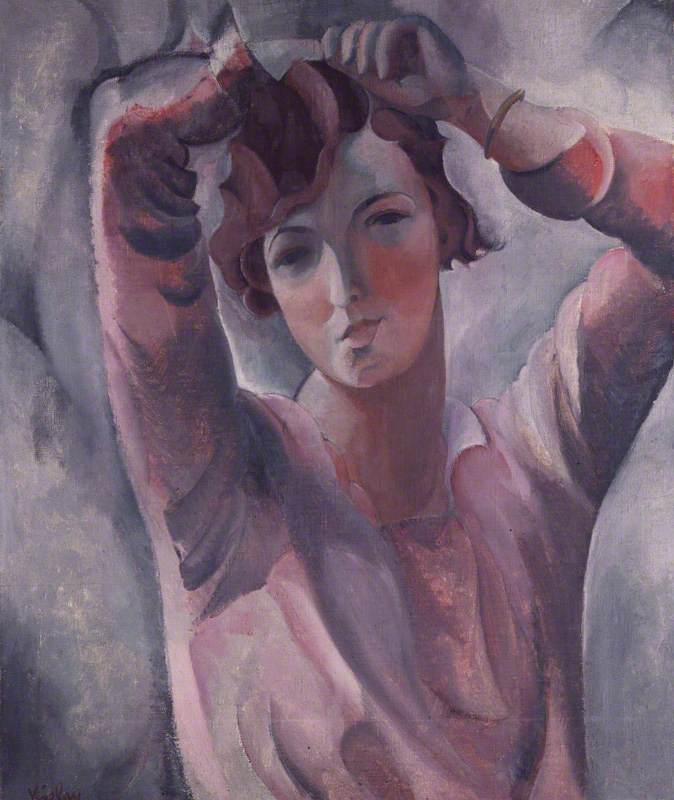

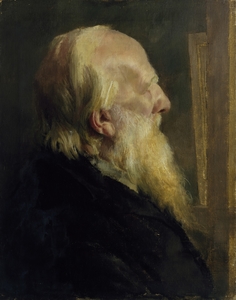

Parker, born in Bury, Lancashire in 1904, came to London in 1923 to take up a place at the Slade School of Art, where she studied under Henry Tonks and Philip Wilson Steer. She was just 19, so her father asked his 34-year-old cousin, an assistant keeper at the British Museum, newly returned from Leonard Woolley's famous excavation at Ur, to look out for her. They married in 1927, the year after she left the Slade. By then, Parker's career was promising – she won first prize for a portrait of an old man, now in the University College London collection, and exhibited with the New English Art Club (NEAC), though according to her son she was too shy to accept an invitation to work with Rex Whistler on decorations for the Queen Mary luxury liner.

Their son Henry, known as Harry, was born the following year, but in late 1928 Smith accepted a secondment to the Assyrian Antiquities Service and the Iraq Museum – on the recommendation of his predecessor Richard Cooke, who would soon become embroiled in controversy over antiquities dealing. The couple moved to Baghdad, leaving little Harry in England with a nurse.

In 1930 the 40-year-old Agatha Christie agreed to marry Max Mallowan, a rising star in Middle Eastern archaeology who had joined Woolley's excavation straight from university. The match raised eyebrows and not merely because Mallowan was 15 years her junior. It was just four years after an episode as famous as anything in her books, when she fled from a disintegrating marriage to Archibald Christie, and vanished for ten days before being tracked down to a hotel in Harrogate, making headlines across the world. They were finally divorced in 1928.

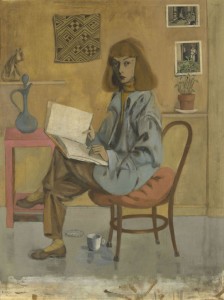

Agatha Christie (1890–1976), Seated, Surrounded by Objects

c.1932–1937

Dora Altounyan (1886–1964)

The second marriage was for life, and very happy. The famous quote, about the wisdom of marrying an archaeologist because the older one became the more interesting one was considered, was invented by a journalist. However Mallowan did apparently ask if Christie objected to his profession of 'digging up the dead', and she is said to have replied 'not at all, I adore corpses and stiffs'.

Both couples entertained widely in the academic and archaeological community in Baghdad. Christie often accompanied Mallowan on excavations – he moved to the equally starry site of Nineveh partly because Christie said wives were made unwelcome at Ur – and famously used luxury face cream to clean some of the beautiful ancient ivories. Her catering contributions, with three-course dinners every night and cake for tea every afternoon – helped make places on Mallowan's teams very popular.

The two women remained friends after their husbands' expanding careers separated them, and Christie dedicated her 1942 novel The Moving Finger to her. Parker was renowned for giving away paintings, and kept few records of sales, so the street scene was almost certainly a gift to Christie. Just such a street in Baghdad is described in the 1936 novel Murder in Mesopotamia ('dedicated to my many archaeological friends in Iraq and Syria'), not as the two women saw the city they loved, but through the gruesomely practical eyes of Nurse Leatheran: 'The dirt and the mess in Baghdad you wouldn't believe – and not romantic at all like you'd think from the Arabian Nights! Of course, it's pretty just on the river, but the town itself is just awful – and no proper shops at all. Major Kelsey took me through the bazaars, and of course there's no denying they're quaint – but just a lot of rubbish and hammering away at copper pans until they make your head ache.'

Parker and Smith returned to London in 1930 when he was appointed Keeper of Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum. They bought a house in Belsize Park, where their daughter Zoe was born in 1933. On the outbreak of war, Parker brought the children to stay with her parents in Bury, until Zoe was evacuated to the United States, and Harry went to boarding school. Smith stayed on in London until their house was badly damaged – destroying many of her canvases – and later demolished in the Blitz. In 1943 the family reunited in accommodation at the Museum itself until Smith retired on grounds of ill health in 1948. He then became Professor of Ancient Semitic Languages and Civilisation at UCL, and they moved to a flat in South Kensington where Parker continued to paint in a corner of the landing.

Parker continued to exhibit, with four paintings exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1947 and 1948, including portraits of Zoe – titled Reflection, and now in the Bury Art Museum – and Harry as a Cambridge undergraduate.

Harry Smith

oil on canvas by Mary Winifrid Smith (1904–1992)

She continued to exhibit both at the RA and the NEAC in most years up to 1965, and also often supplied illustrations for her husband's academic publications.

Girl with a Book

(the artist's daughter, Zoe) 1947

Mary Winifrid Smith (1904–1992)

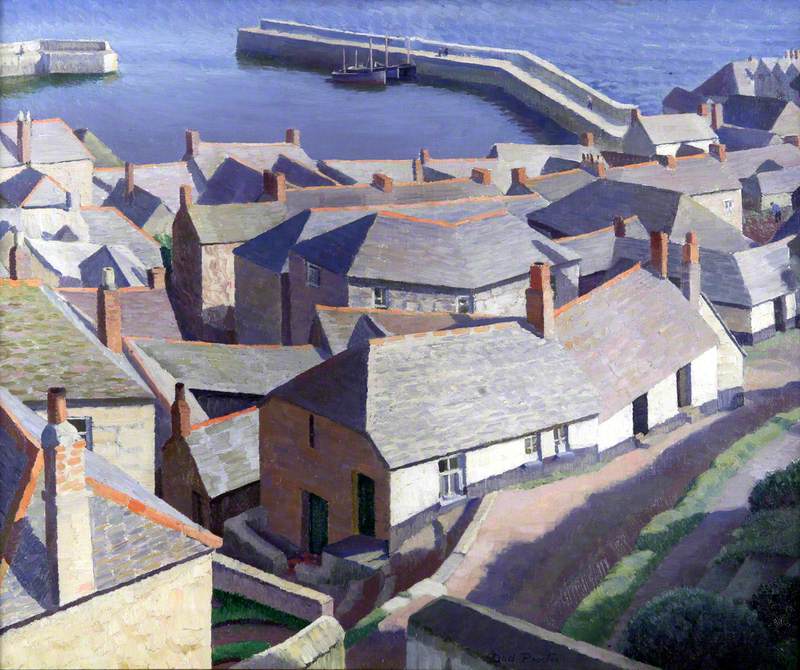

When Smith retired again in 1955 they moved to Barcombe, near Lewes in Sussex, which inspired paintings of local scenes, including a lovely sombre view of a Sussex farmhouse exhibited in 1962, bought by London County Council and now in the Lewisham collection.

Zoe married John Swinburne Ellingworth in 1959, and in 1961 emigrated to Australia, where John had grown up and had business interests. Harry became Edwards Professor of Egyptology at UCL, and curator of its Petrie Museum with its extraordinary collections from Ancient Egypt, and is still living in retirement in London.

Harry, in a message to this writer, says that his mother was a good artist who deserves better recognition, and that his father very much wanted her to continue her painting career. He believes her career was stalled both by the demands of family, his father's frequently poor health, and the move to Baghdad which interrupted her links with contacts in the London art world. In addition, he said, Mary was of a quiet and shy disposition, never one to thrust herself forward.

One of the last pieces of the jigsaw came all the way from Australia, from Mary's grandson Giles Ellingsworth, who recalled that she came to live with them in Melbourne in 1982, following her diagnosis of dementia after Sidney's death in 1979. She died there in 1992. His mother Zoe still lives nearby – and still, he said, has the eyes of the girl in the portrait in the Bury museum.

His family still treasures a number of her paintings, including one of a young Iraqi boy made around the same date as the street scene. 'They are all beautiful pieces,' he wrote, 'and we are slightly bemused that she never was recognised for her work.'

Maev Kennedy, writer