Having spent my entire working life in the art world, many – if not all – of my heroes are artists.

It all began back in the early 1970s when I landed a job at the prestigious Thomas Agnew Gallery at 43 Old Bond Street, London (the building is listed and currently a branch of the fashion chain Etro). I popped in the other day and very little has changed – the ground floor rooms and gallery spaces are as I remember them. Only the original dark mahogany doors have been removed, otherwise the central greenhouse space is still there, as is the upstairs gallery, along with the deep red flock wallpaper.

In my time there, this was a very seductive place – among our clients were the owners of the grandest estates and houses along with the super wealthy international clients, most notably the 'two Pauls': Mellon and Getty. I was sucked willingly into this world with all its differing styles and periods of art.

In 1975 I counted 17 works by Turner in our stock. However, it was modern British art and its artists that drew me in. To me, it seemed much more approachable, real, recent and fun.

Unlike our mainly Old Master and nineteenth-century stock, some of the artists I liked such as Duncan Grant were even still alive! I did meet Duncan in the summer of 1974. All the senior gallery staff were away on holiday and Old Bond Street was as quiet as the grave, so I was allowed to choose the works for the re-hang in our two bay windows looking out on the Albermarle Street entrance.

I chose to fill both windows with our entire stock of pictures by Grant who, by an extraordinary coincidence, was passing in his wheelchair right past our windows at the very same time. He was dressed in all white, topped off with a wide-brimmed Panama hat. He was with his carer and they stopped to look – I waved from the window and invited them in. Duncan seemed delighted to see so much of his work in the window and stayed talking for ages about where, when and how he painted each picture.

Not long after my encounter with Duncan Grant, I met the delightful Bernard Dunstan who was a regular gallery artist. I used to help hang his shows and he and his his wife Diana Armfield lived to paint and painted to live, and so for them a successful show was key – they took a keen interest in all elements.

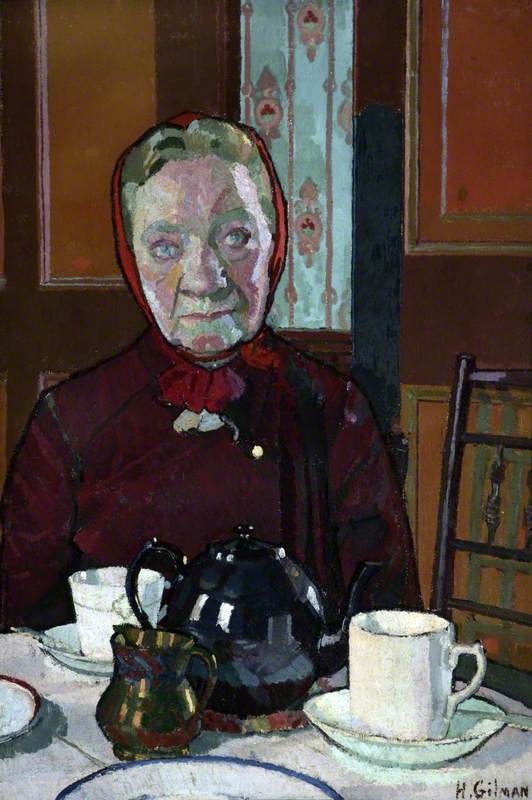

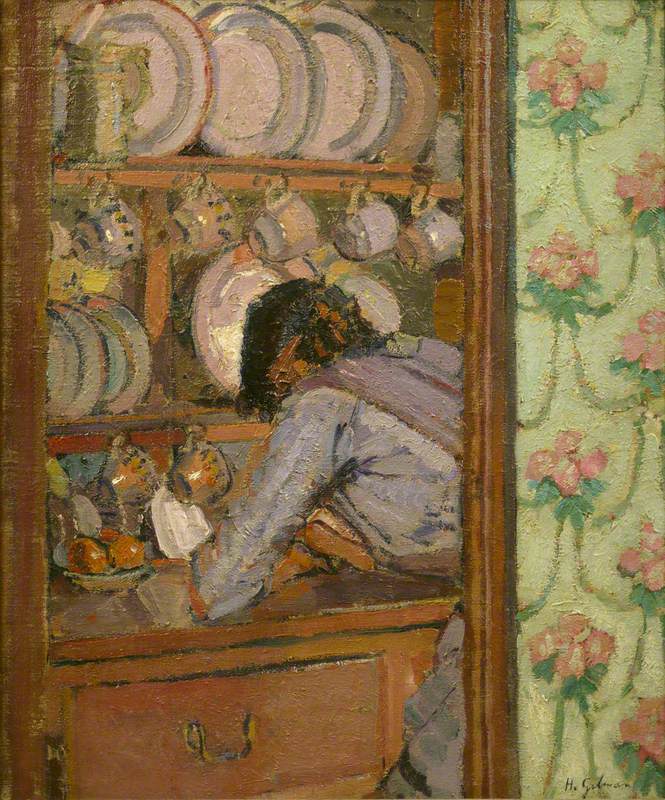

The following year we showed Peter Brook, whose work is now experiencing a market renaissance. Later that year we had a Camden Town selling and loan exhibition that included Harold Gilman's Mrs Mounter which got me hooked on the Camden Town painters.

I went on to meet Frederick (Freddie) Gore who, when I asked him about his father Spencer Gore, politely told me that everyone asks him that. As his father died when he was a baby, there was nothing he could tell me or anyone.

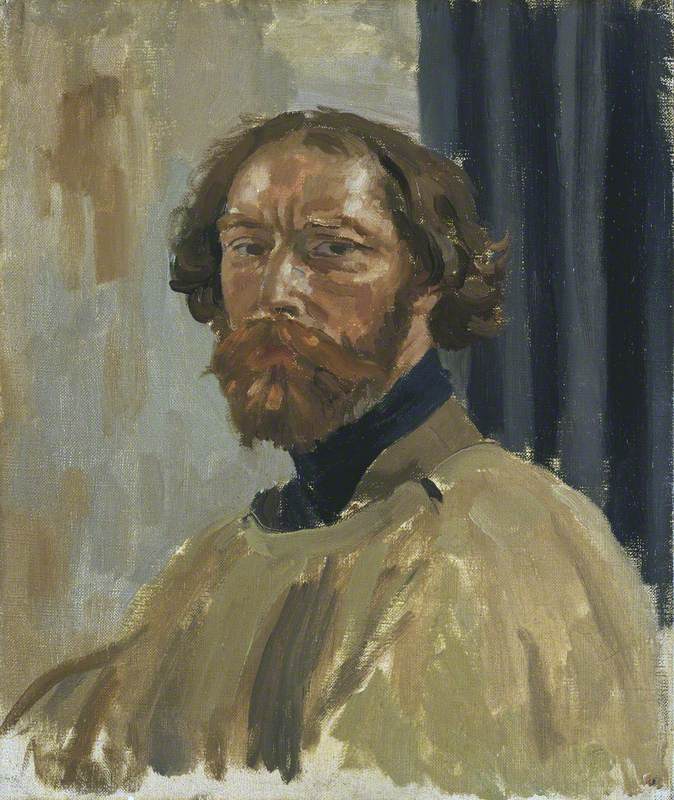

I left Agnews in 1976 to join Christie's, where the sheer volume of art I saw far exceeded my expectations. I discovered the work of Augustus John and William Orpen, YBAs of their time and both brilliant draughtsmen. I began to meet people who knew both artists and one particular meeting stands out. I was working on an over full-length portrait by William Orpen of Mrs St George, belonging to the sitter's grandson. Orpen had had a longstanding love affair with Mrs St George while both were in Dublin in the years before the First World War.

'Orpsy', as he called himself, was 5 feet 3 inches, and Mrs St George was very nearly six feet tall. In Dublin circles, they were known as 'Jack and the Beanstalk'. I had not yet met the picture's owner and he arranged to come and see me one afternoon. When he arrived I was totally tongue-tied as to all intents and purposes, judging from every middle-aged photograph of Orpen I had ever seen, there standing in front of me was the living embodiment of Orpen himself – same height, distinctive face and features, receding hairline, sloping forehead... The owner broke the silence by saying 'yes I know what you are thinking – my Granny was a little indiscreet and as you can see I am the result of their union.'

I was utterly charmed by him and the whole back story, the picture went on to sell extremely well and everyone was happy. I also felt I had learned something unique about Orpen the man through this experience.

A few years later, in 1993, I found myself hosting an 85th birthday party for the Royal Academician Carel Weight. We had hung a small group of his pictures. All were chosen by Carel, as were all the party guests for a celebratory drink. However, on the night of the party, one key person was missing – Carel himself! His friends had all told me that he was always very late. I had convinced myself that he would surely arrive in good time for his own party. Not a bit of it – he was super late and arrived long after the speeches and toasts. None of his guests were in the least bit bothered or surprised.

When he finally arrived most people had left. Carel was quite content to wander around the now-empty room looking at his pictures with me in tow and shared a few personal memories. He told me that as a young child of about six, his mother placed him with a childminder in Fulham during the week. The childminder had so many babies and younger children to look after that she would let him wander off on his own wherever and whenever he wanted, just as long as he came back in time for tea.

Thus Carel found himself observing the world from the outside, rather like L. S. Lowry who taught Carel during his time at the Royal College of Art. I remember one very dramatic painting in the show – a terrified woman, arms outstretched at a first-floor window of a house in a Fulham street. The house was on fire and the fire engines were racing to attend, the flames had reached roof level.

I asked Carel about it, and he told me he witnessed the whole scene at first hand on one of his street jaunts, aged about eight or nine.

I regularly saw Carel and the equally delightful Mary Fedden once a month at the RA during meetings of the Artists General Benevolent Institute, a charity that provides for artists that fall ill or are in difficulty.

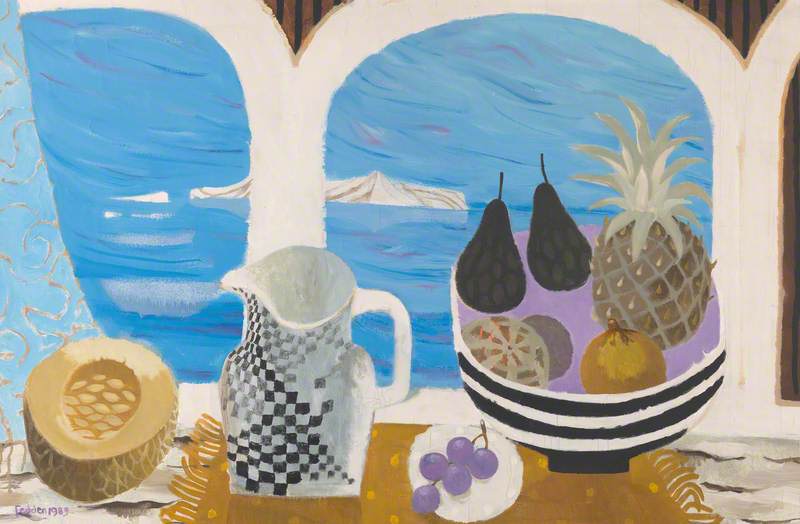

After one meeting I remember Mary telling us that she effectively reined back her painting career following her marriage to Julian Trevelyan, as was the convention at the time. She only began in earnest again in the early 1980s a few years after Julian died. Such was the enthusiasm for her work that queues of eager buyers formed along the length of Cork Street at her exhibitions.

This leads me to L. S. Lowry, an artist whom I never met and whose life and character I have learned about from his friends, patrons, dealers and neighbours – particularly his near neighbour in Mottram, Lawrence Ives. Lawrence was a consultant psychiatrist, and Director of the Greater Manchester area health authority. He and his wife Daphne visited Lowry regularly as he only lived 150 yards away up a lane. From their first meeting in 1959 until Lowry's death, Lawrie and Daphne built up a collection of 17 pictures and drawings by Lowry which we sold for them in 2000. Tantalisingly, Ives told me that Lowry often wandered down to see him late at night for a chat but that his friendship and profession prevented from telling anyone what they spoke about over the years. He would often start telling me something and then stop himself.

Of all our modern British painters, Lowry is a very English taste and the best-known artist among the general public. Also, for some reason, he is the only artist collected in quantity, often by people whose only interest is Lowry. The variety, range and subtlety of Lowry's work makes this perfectly possible.

I think the mental picture people have of Lowry's art is dominated by what I call his 'signature' pictures – industrial landscapes or town scenes with figures. For me, as good as this work is, there is a great deal more to Lowry than just these works, such as his minimalist seascapes and empty haunting landscapes. I have always found Lowry fascinating both as a painter and as something of a mystery man who continues to surprise me.

Jonathan Horwich, art historian