Just before the Isle of Lewis becomes the Isle of Harris, an extraordinary piece of public art towers above the main road, unmissable to any driver. Unveiled in 1994, Lewis's first Cuimhneachain nan Gaisgeach (Land Struggle Cairn) is both a physical and cultural landmark.

Memorial to the Pairc Deer Raiders: Cuimhneachain nan Gaisgeach (Land Struggle Cairn)

Will Maclean, John Norgrove, James Crawford

The cairn – in the words of the project's main instigator, Angus Macleod – is 'dedicated to the memory of the people of Lochs who laid claim to the dispossessed land of their forebears and challenged the authority of the State to spotlight the poverty and injustice they suffered under the oppression of heartless landlords'.

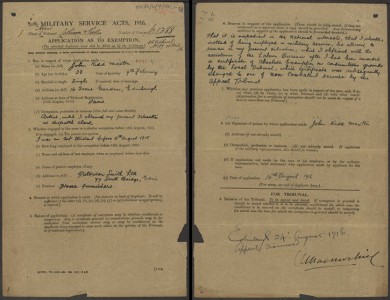

It commemorates a famous incident in November 1887, when around 200 Lewis men entered the local estate, shot some of the landowner's deer, and cooked and ate them.

Six of the men were put on trial at Edinburgh's High Court. All were found innocent; the verdict prompted a wave of further land protests across Lewis.

The dramatic story of the Park (or Pairc) Deer Raiders is recounted in detail in Joni Buchanan's 1996 book The Lewis Land Struggle. Significantly, the raid took place the year after the 1886 Crofters Act.

Described by Buchanan as 'the most fundamental piece of legislation in crofting history', the act provided security of tenure for crofters after years of being evicted by landowners to make way for large-scale sheep and cattle farming – the infamous Highland Clearances.

In the long term it would be transformative, but at the time it was too little too late for people who were already starving and desperate. By the 1880s, Buchanan writes, there were up to 300 landless families in the area, squatting on other people's crofts.

Something had to give, and between the 1880s and early 1920s it did – protest by protest and raid by raid. The Park Deer Raid lit a spark that gradually became a fire.

Aiginis Farm Raiders Monument: Cuimhneachain nan Gaisgeach (Land Struggle Cairn)

Will Maclean, John Norgrove, James Crawford

Buchanan's book, she acknowledges, is written 'unashamedly from the crofters' point of view'. That approach also informed the three remarkable sculptures built between 1994 and 1996 as part of an ambitious community-led project, Cuimhneachain nan Gaisgeach (Memorials of the Heroes).

The memorial to the Park Deer Raiders was the first. It was followed by two more, at Aignish (or Aiginis) and Gress, each inspired by a different incident in the island's long history of land protests (there was to be a fourth in Bernera but the community there opted to create a smaller-scale cairn themselves).

In 2012, work began on a fourth sculpture, An Suileachan, at Reef in Uig, on land newly acquired by Bhaltos Community Trust.

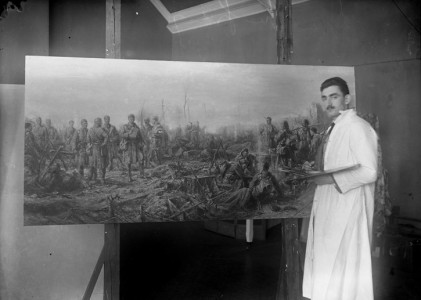

'They're not modern art parachuted into a community,' emphasises artist Will Maclean, who worked on all four (his wife and creative collaborator Marian Leven also worked on An Suileachan).

'They were commissioned by the community and as an artist, I was just part of a unit of people who brought these things to fruition.'

This unit also included stonemasons James Crawford and Ian Smith, who built the cairns, and teams of local people – too many to list here – who worked together on project management, planning applications, and events to mark the opening of each sculpture.

In each case, the local community decided on the location and the design. 'Each one had its own discussion,' recalls Maclean. 'From a design point of view, each of the incidents was visually different.'

In the case of the Park Deer Raid cairn, the sculpture was built with three entrances to mark the three ways the raiders entered the estate. Inside, a staircase leads you up to a viewing platform – the top of the sculpture is built from stones from the houses of the raiders who were put on trial.

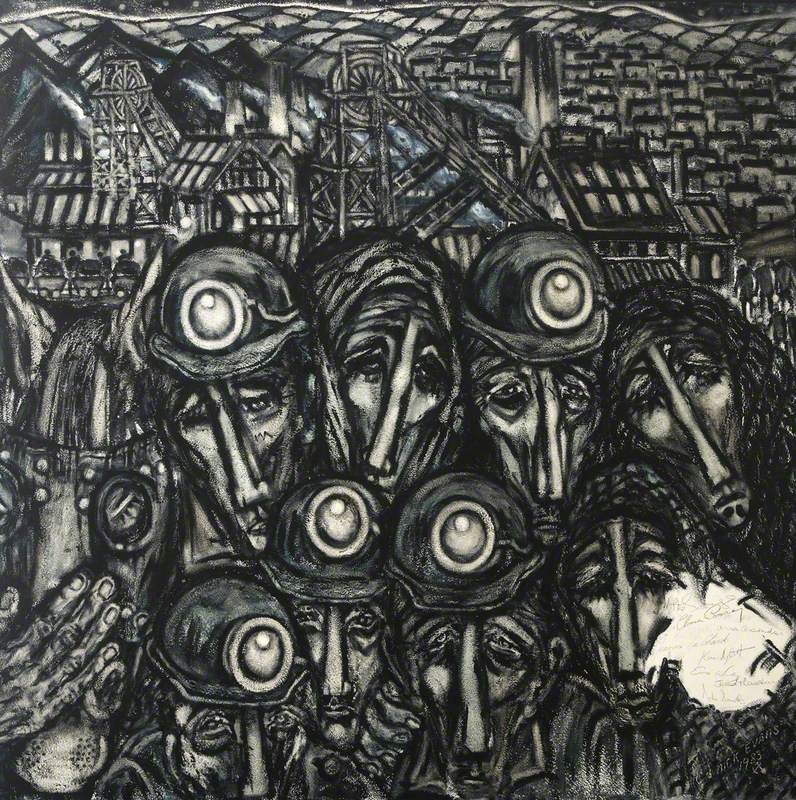

The Aignish Riot took place just a few weeks after the Park Deer Raid, in January 1888, as a group of around 400 people raided Aignish farm in an attempt to drive cattle off the land and reclaim it for small-scale crofting.

The result was a dramatic and bloody confrontation with police and marines armed with bayonets. The design of the sculpture, built close to the site where the confrontation took place, reflects the tension of the day; it resembles a cairn violently ripped into two.

The sculpture at Gress references a much later confrontation, in 1919, when Lord Leverhulme, then owner of the Isle of Lewis, addressed a crowd of crofters in an attempt to win them over to his way of thinking.

Memorial Cairn to the Gress and Coll Raiders: Cuimhneachain nan Gaisgeach (Land Struggle Cairn)

Will Maclean, John Norgrove, James Crawford

The sculpture – with its rectangular central column, like a modern industrial building, flanked by a more organic, traditional, cairn-like exterior – represents the ideological gulf between Leverhulme and his audience, and between large-scale landowners and crofters in general.

Leverhulme had ambitious plans to industrialise Lewis, through fish canning and using the farms around Stornoway for mass production of milk. But he faced formidable opposition from islanders who had just endured four years of war and were even more determined to exercise their right to work the land for themselves and their families.

William Hesketh Lever (1851–1925), 1st Viscount Leverhulme

1924

Philip Alexius de László (1869–1937)

Part of this story, of course, is the Iolaire disaster of New Year's Day, 1919, in which 200 Lewis men returning from the First World War drowned in a fierce storm less than a mile from Stornoway. Alongside the bodies washed up on the shore were Christmas presents for their families.

The intense cruelty of this tragedy traumatised the island for generations, but in the short term, it made the fight to return land to ordinary people all the more urgent. And so it is fitting that the Iolaire Centenary Sculpture, also designed by Will Maclean and Marian Leven, along with Arthur Watson, has a similar aesthetic to the land struggle sculptures (and to An Suileachan in particular – both were conceived as places for gathering and reflection).

Iolaire Centenary Sculpture

2019

Will Maclean, Marian Leven, Arthur Watson

Something else the Iolaire sculpture and the memorial cairns have in common is that they are both long-awaited acknowledgements of often hidden histories. The Iolaire disaster's psychological impact on the island was so profound that it was barely talked about for decades. And Hebridean history has largely been told from the perspective of the landowners. It wasn't until the 1970s that the injustices of the Highland Clearances began to get widespread attention.

The public response to the memorial cairns reflects this. Malcolm Maclean, a co-founder of An Lanntair arts centre in Stornoway, was involved in all four sculpture projects. He vividly remembers the opening of the first cairn in 1994, which included a procession of over 100 people from nearby Balallan, Gaelic psalm singing, and a ceilidh featuring 'every musician associated with the area' including the famous singer Calum Kennedy, performing there for the first time in 30 years.

Afterwards, a man approached Maclean and insisted on giving him a £10 note. 'We told him, no no, it's all free. He said, I know, I've been here all day. Just do more things like this.' By the time of the Aignish opening, he recalls, crowd numbers had swelled to over 1,000.

Both Malcolm Maclean and Will Maclean are keen to share a memory of John Mackay, son of one of the Aignish rioters, who took part in the official opening of the Aignish cairn. 'He told me that to begin with, it had been a cloud over his family for his father to have been put in prison,' recalls Will Maclean, 'but within his lifetime it had turned into an amazing celebration of this group of people.'

An Suileachan

Will Maclean (b.1941) and Marian Leven (b.1944) and John Murdo Macleod (1922–2018)

An Suileachan is perhaps the most obviously celebratory of the four artworks. A lot happened between 1994 and 2012 to change the narrative around land ownership in Scotland: the publication of Andy Wightman's book Who Owns Scotland in 1996, the community buyout of the island of Eigg in 1997, the formation of the Scottish Parliament in 1999 and, most obviously, the Land Reform (Scotland) Act of 2003 and its aftermath.

'An Suileachan was quite different,' notes Will Maclean, 'in that it was as much a celebration of the return of the land to the community.' This is reflected in the design, with its circle of benches and brazer for lighting a communal fire (built from century-old graveyard railings by Stornoway blacksmith John Macleod).

'As years have gone by, what pleases me most of all is that people have adopted the memorials as part of their community activity,' says Maclean. 'They're a living thing.'

An Suileachan

Will Maclean (b.1941) and Marian Leven (b.1944) and John Murdo Macleod (1922–2018)

It is largely thanks to the raiders that these communities exist at all, says Joni Buchanan. 'Lewis, down to the present day, retains a substantial rural population for one reason above all others,' she writes. 'It is that, at crucial points in the island's history, its people were prepared to resist the power of landlordism and insist on their right to remain on the land which they occupied.'

An Suileachan

Will Maclean (b.1941) and Marian Leven (b.1944) and John Murdo Macleod (1922–2018)

It's humbling, as a recent addition to that rural population, to discover all this history. Uig in 2021 is a thriving and closely-knit community including numerous families with crofts; my own family's life here began with a croft becoming available in 2017.

The family names of the Reef Raiders, engraved in An Suileachan, still make up much of the register at the area's well attended primary school. My nine-year-old daughter's best friend, who lives a short walk from An Suileachan, is one of their direct descendants. Her mother runs a mobile catering company called the Raider Trailer.

Andrew Eaton-Lewis, freelance writer

This content was supported by Creative Scotland

Further reading

Joni Buchanan, The Lewis Land Struggle, Acair, 1998

Andy Wightman, Who Owns Scotland, Canongate, 1996