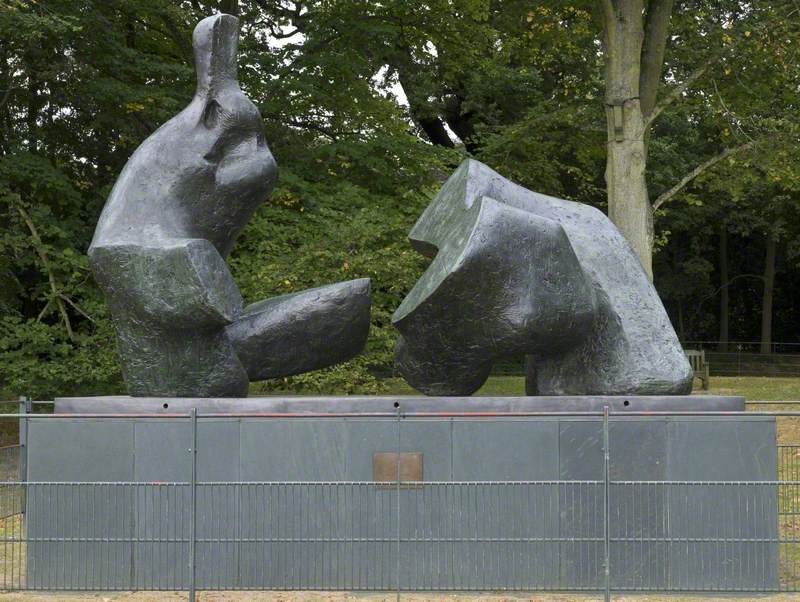

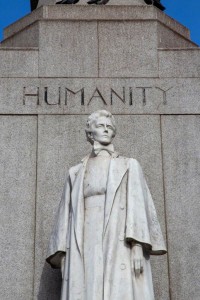

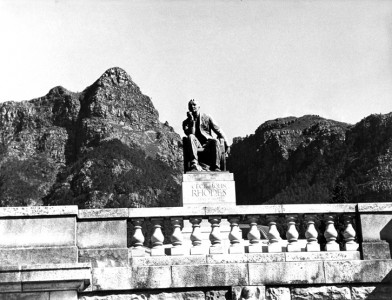

The recording and photographing of outdoor public sculpture is an important aspect of the Art UK sculpture project. More so than ‘collection-based’ sculpture, the monuments, statues, and even what we would class as ‘street furniture’, are fully woven into the fabric of our everyday lives.

As markers on the landscape, they are objects that contribute to navigation around our towns and cities, and, as manifestations of socio-political values and traditions, they are one of the fundamentally accessible ways in which we can learn about history, particularly that of our local area.

Volunteer photography in action

Reflecting design and aesthetic opinions of the time at which they were constructed, they also provide a means of measuring changing tastes in the production and consumption of public sculpture. Our public monuments can help us to understand cultural memory in each passing generation. They are some of the most emphatic contributions to developing a sense of place and community identity.

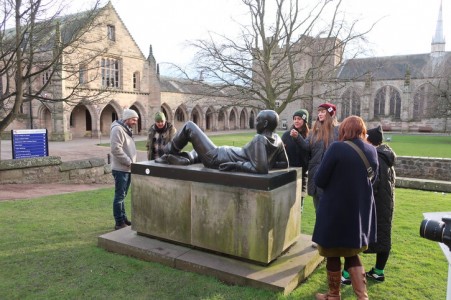

There are currently 130 Art UK sculpture volunteers all over the country, diligently researching and photographing public sculpture in their local areas. Thousands of images have already been taken, from the far north of Scotland to the Channel Islands. We are still in the process of recruiting and training even more volunteers, and the enthusiasm to help with the project seems undiminished.

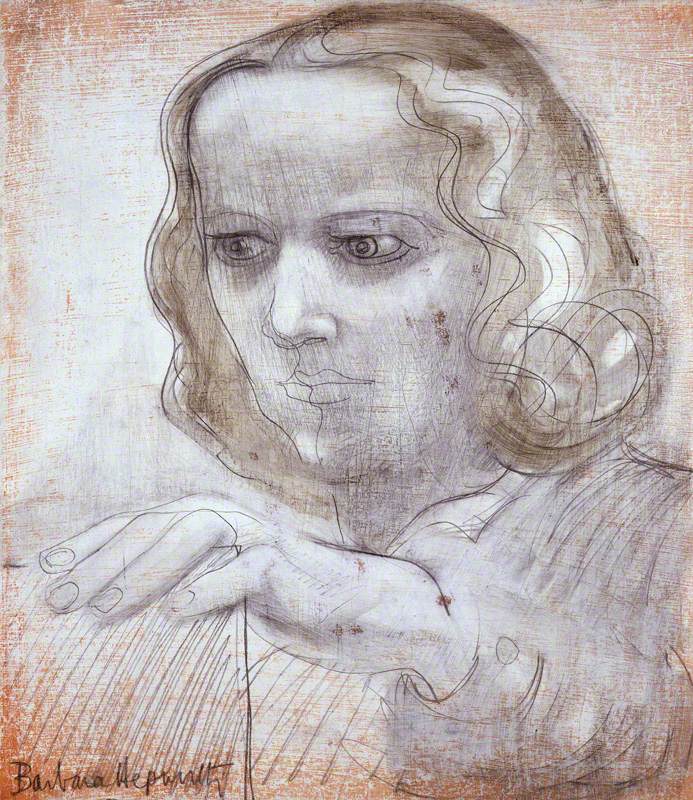

Volunteer photographers

Many of our photographers have come to us through their membership of the Royal Photographic Society, who have been enormously supportive of the project. The skills and experience of our photographers vary, however, and many who are less experienced are benefiting from the type of learning opportunities that

The comment that I perhaps hear most from volunteers is that, in helping Art UK, they have learnt such a lot about where they live. The unconscious familiarity we often have with local monuments – these ‘markers’ on our local landscape, often means that we rarely truly ‘see’ them, and a project such as ours can improve our ‘vision’ with regard to the sculptural heritage of our cities, towns, and villages.

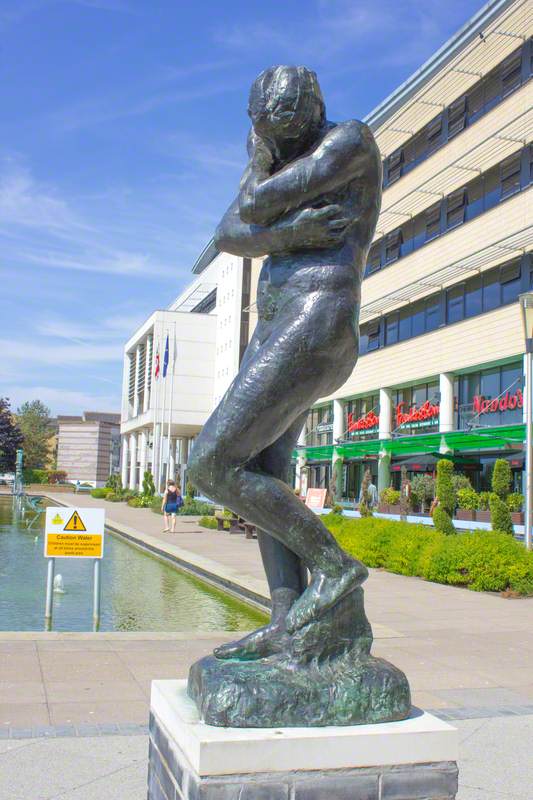

The breadth of object types that we are recording as part of the public sculpture aspect of the project is extremely wide. From the sculptural benches, drinking fountains, and waymarkers, right up to the monumental commemorative structures, war memorials and iconic landmark sculptures.

Jubilee Drinking Fountain in Bury, Greater Manchester

erected 1897, sculpture by T. R. Kitsell (architect)

Many of them are perhaps often considered ‘insignificant’ objects, but they can have an extremely important position both in historical

Matilda Drinking Fountain in Camden, London

erected 1878, bronze statue by Joseph Durham

Commemorative statues to ‘the great and the good’ abound all over the country, many erected in the mid-1800s at the height of a period referred to as ‘Statuemania’; there can also be few towns and cities that do not have a statue of Queen Victoria. We also find, however, statues to individuals who have a specific place within the history of the local area, often hidden away in unusual locations.

Big Jim Larkin, Donegall Street Place, Belfast

erected 2006, sculpture by Anto Brennan (mural, 2013 by Danny Devanny and Mark Ervine)

On a recent trip to Belfast, I found a statue of Jim Larkin, the Irish republican, socialist and trade union leader, affixed to a wall down an alleyway, around which a mural had been painted. It is on the gable wall of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions office in the Cathedral Quarter of the city. This is close to Waring Street, where Larkin led the Belfast dockers’ strike of 1907. Recording such objects on the Art UK website not only provides important information about history but also helps us to find these, often somewhat hidden, sculptures through its mapping function.

There can also be few cities, towns and villages that do not have a war memorial. Again, through its volunteers, Art UK is surveying and photographing a wide range of these. While recognising the important work that the Imperial War Museum has carried out through its War Memorials Register, a comprehensive national database of UK war memorials, Art UK is primarily interested in those that have a significantly sculptural element.

‘Lions of the Great War’ Memorial, Smethwick, West Midlands

erected 2018, sculpture by Luke Perry

The recent commemorations marking the end of the First World War, in particular, resulted in the erection of several new war memorials to those lost in that conflict, such as the ten-foot-high memorial Lions of the Great War, unveiled in Smethwick on 4th November 2018. The plinth is surmounted by a bronze statue of a Sikh soldier. It is the UK's first statue of a South Asian First World War soldier.

‘Eyemouth Widows and Bairns’, Eyemouth, Scottish Borders

erected 2016, sculpture by Jill Watson

War memorials are not the only monuments that commemorate the loss of life of course – many local communities have erected dedicatory sculpture to those who died in local disasters, such as the magnificent memorial to the ‘Eyemouth Widows and Bairns’ by the sculptor Jill Watson. It remembers those local fishermen who lost their lives in the great storm of 14th October 1881. Each individual character in the sculpture represents one of the bereaved.

Eyemouth 'Widows and Bairns’ (detail)

erected 2016, sculpture by Jill Watson (b.1957)

Public sculpture frequently reflects contemporary debate about socio-political issues. The debate around the lack of public statuary that depicts important women has been one that has now continued for many years but, happily, this appears to be changing with increasing momentum. The erection last year of several statues to key women involved with the women’s suffrage movement was an indicator of this. Not only did these statues finally pay homage to these incredibly brave and powerful women but, erected in towns where they had particular significance, they contributed to a sense of local pride and community identity.

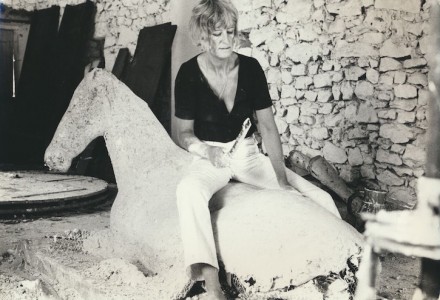

The sculptor Hazel Reeves (left) with Helen Pankhurst (right)

In front of the statue ‘Rise Up Women’, depicting Emmeline Pankhurst, St Peter’s Square, Manchester, by Hazel Reeves, erected 2018

The sculpture of Emmeline Pankhurst in Manchester, by sculptor Hazel Reeves, was perhaps the greatest demonstration of this. The unveiling was accompanied by literally thousands of people who marched to St Peter’s Square for the event, including around a thousand schoolchildren. The unveiling was attended by Helen Pankhurst, the Suffragette’s great-granddaughter.

The impetus to address the imbalance with regard to the lack of public statues to important women continues. Hazel Reeves has also been commissioned to create statues of Mary Clarke, the Brighton Suffragette, and Mary Anning, the Lyme Regis-born palaeontologist. Other projects are ongoing for statues to Nancy Astor in Plymouth, the first woman to take up an elected seat in the House of Commons, and one of Barbara Castle MP in Blackburn. The Art UK database will eventually make it possible, for the very first time, to search a national database of public sculpture and to discover not only the number of statues of women from

This is an exciting time, for researchers, and for those who are simply interested in the public sculpture that punctuates the roads, streets, and parks of their local area. The Art UK website will provide a means for us to answer questions that we have long wished to know the answers to with regard to public sculpture, but it will also act as a springboard for a new and more nuanced appreciation of the incredibly rich sculptural heritage that we possess.

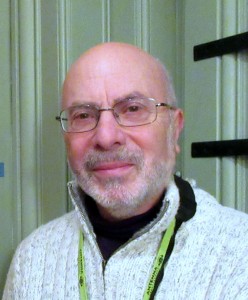

Antony McIntosh, Public Sculpture Manager, Art UK