History is a slippery beast, and the past is a living, breathing thing.

The senses as we know them are deeply bound up with structures of power, and the opposition between the mind and body has long been correlated with an opposition between male and female. From the eighteenth century onwards, European Imperialism relied heavily on strengthened and enforced modern categories of difference – race, gender, sexuality, and religion.

Alongside a burgeoning ideal of the hyper-masculine European male, senses pertaining to the mind, such as reason and rationale, which were traditionally associated with 'masculine' pursuits such as science, were privileged. The body, however, was regarded as inherently feminine, 'other': something to be tamed and even feared, with women deemed more corporeal than their male counterparts. Historically, there has been a sense of scepticism and even suspicion with regard to being 'in' your body.

© the artist. Image credit: Christabel Beddoes

Asoebi

sculpture by Sokari Douglas Camp (b.1958). The installation of five colossal steel sculptures will be outside Morley Gallery in the community garden until 15th November 2023

Today, there is recognition that bodies are retainers, of history, memory, and trauma. Contrary to what people may believe, trauma is not primarily an emotional response, rather, it always occurs in the body. Indeed, trauma – including historical, ancestral and intergenerational – can physically be mapped in the body, and recent research suggests it is even passed on in our DNA, inextricably linking us to our history and ancestral past, as our bodies house the unhealed dissonance of our ancestors.

© the artist. Image credit: Christabel Beddoes

Undule 1

sculpture by Adaesi Ukairo

However, just as trauma occurs fundamentally in the body, so does healing. As Resmaa Menakem notes, resilience is also built into the cells of our bodies, and one characteristic that nearly all human bodies share is a profound ability to heal. When we heal, this ripples outwards, spreading health and resilience from generation to generation. Throughout time, black and brown women's bodies have been oppressed, othered and objectified. Today, and always, being in your body is a radical act of resistance.

© the artist. Image credit: Christabel Beddoes

Asoebi

sculpture by Sokari Douglas Camp (b.1958)

'The body is where our instincts reside and where we fight, flee, or freeze, and it endures the trauma inflicted by the ills that plague society.' – Resmaa Menakem, My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Mending of Our Bodies and Hearts

Scholars and experts have widely discussed the limits of language to describe the experiences and sensations of the human body. In The Body Remembers, somatic trauma expert Babette Rothschild discusses the clumsiness of the English language when it comes to differentiating the conscious experiences of emotions from bodily sensations: the word 'feeling' usually stands for both. Nevertheless, everyday phrases – across many languages – encapsulate the interconnectedness of emotions and bodily sensations: we carry tension, we hold trauma.

Consider how much of the language around emotions is weighted. Sculptural works, such as those of Sokari Douglas Camp and Adaesi Ukairo bear the physical, palpable heaviness of being.

© the artist. Image credit: Christabel Beddoes

Asoebi

sculpture by Sokari Douglas Camp (b.1958)

Douglas Camp's sculptures, welded primarily in steel, explore the history and contemporary socio-political issues relating to the African diaspora, whilst often making reference to her Nigerian heritage.

Londoneer (2010) is an ode to the impossibly well-dressed West African women of London. The figure balances a handbag casually on one arm and clutches a Tesco bag in the other, instantly recognisable as she does her supermarket shopping. Here, the artist renders the human body a vivid example of tension; we can almost feel the grip of her hand around the bag, and her shoe straps clinging diligently to the spaces between her toes. She is, however, defined curiously through the void. She wears a gele – a Nigerian headwrap – atop her head, with long locks of hair cascading downwards, but she is faceless.

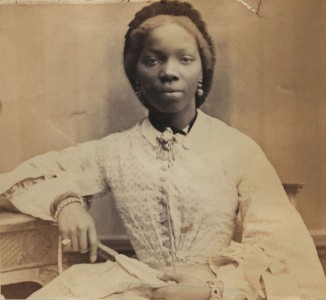

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the artist

Londoneer

2010, sculpture by Sokari Douglas Camp (b.1958)

The artist has made the conscious choice to use the 'Stars and Moon' pattern of the Ankara cloth she wears to create the overall form of the body; much like a silhouette drawing, her being is expressed through the metal's negative space. In this way, the viewer can move not only around the sculpture, but through it – maximising its physical presence.

The emphasis on the fabric points to the status of clothing as a signifier of status and wealth in West African culture, but also, the way in which elements of our culture come to define us, down to our bones. Here, Londoneer is discernible by what is left out, what is not shown: a hint at the artist's ability to see herself – or at least a part of herself – in this woman.

© the artist. Image credit: Christabel Beddoes

Undule 2

sculpture by Adaesi Ukairo

Adaesi Ukairo's sculptures express, in tangible form, the fluid movement of energy of a life lived and the experience that a body holds. Working in copper and brass – so-called 'underdog materials'- Ukairo is drawn to their warmth, richness, and resplendent earthy tones. The artist, who is of mixed heritage, describes an 'entangled feeling,' and views her practice as an attempt to 'reach out and pull oneself out of entanglement' whilst navigating her identity and the dichotomy of feeling visible and invisible at once.

Undule (2022) series – her most free-form pieces – are created using anticlastic raising, transforming a single sheet of metal into an undulating organic form using only a hammer. The artist describes this part of her practice as a 'pure expression of intuition' and a kind of meditation, 'exploiting the elasticity of copper with my hammer and forming stakes.'

© the artist. Image credit: Rod Morris

Undule 3

sculpture by Adaesi Ukairo

Both Douglas Camp's and Ukairo's works poignantly address the fragility, but also resilience of the human body. Steel, copper and brass – incredibly resilient materials – transition when welded, exhibiting a translucent, watery quality when they catch the light. This contrast of seemingly opposing elements – water (fluid) and solid mass (fixed), points to the dynamic, ever-changing states of the body in fight or flight, resistance or rest. Their works exude a remarkable fluidity that seems to defy the constraints and nature of the mediums in which they work.

Bodies of water are significant in Hannah Uzor's work. Driven by her interest in history, diasporic culture and its manifestation in personal and public memory, Uzor's practice draws heavily upon historical research. For her latest body of work, the artist draws upon recent research of the Tonga people. In the 1950s, under the colonial regime, the Kariba Dam was developed by the British Empire along the Zambezi River to electrify the burgeoning industries of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and the copper mines of Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia). The Gwembe Valley was flooded in order to build the dam, which subsequently caused the displacement of around 57,000 people who had lived for centuries along the river, connected to its patterns and conscious of its power.

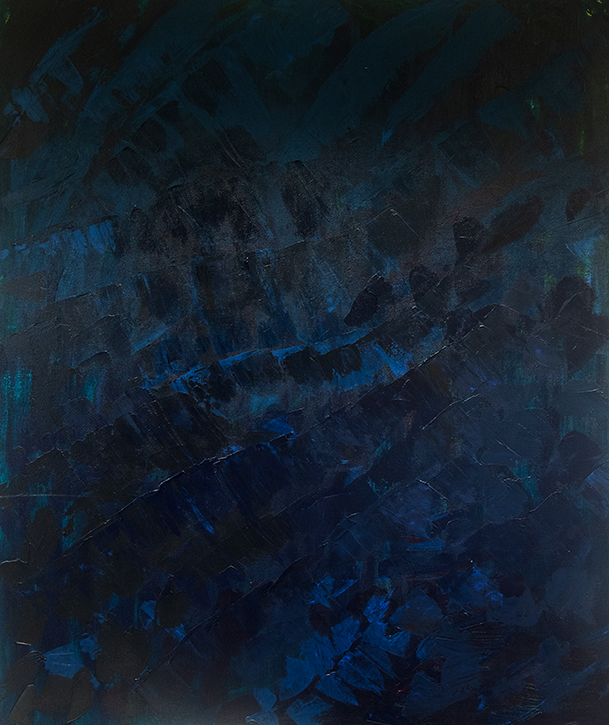

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the artist

Deep Blue See

2023, painting by Hannah Uzor (b.1982)

Deep Blue See (2023) considers what we do when we are in situations that require us to delve deeper. The figure in the painting resides underneath the dark blue water and foliage, but is barely visible to the eye. The mystery of this piece pertains to the things we do not know, or have not been told about our history(ies), and those left out of the mainstream narrative, such as the Tonga people. Similarly, her anatomical works, such as Not All That Glitters II (2023), are a symbolic rendering of body and memory in an attempt to imagine who people were beyond what we collectively remember – making tangible the echo of their presence.

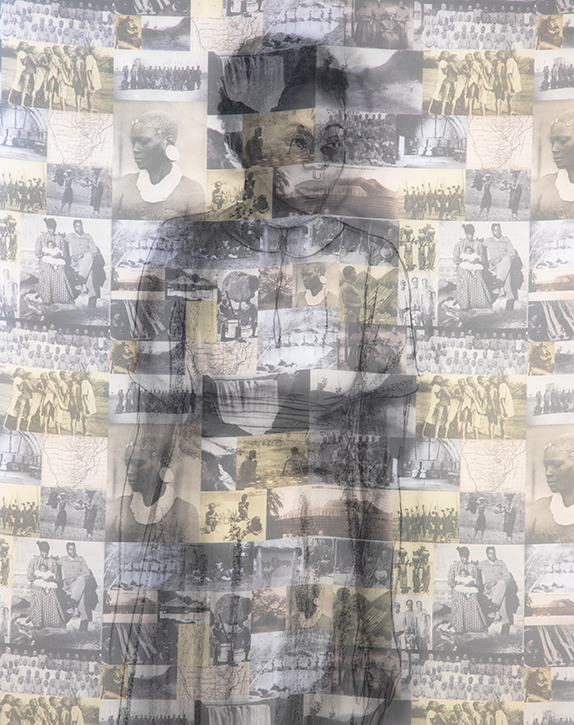

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the artist

Not All That Glitters

2023, artwork by Hannah Uzor (b.1982)

Camilla Dilshat's works provoke an awareness of our own physical presence, as her practice investigates how the body experience forms an understanding of one's diasporic identity, whilst simultaneously shattering one's sense of place. Resting After Fullness (2022), which is comprised of sheep's wool – an important commodity in Uyghur culture – explores the tactility of materials, and the feelings they evoke as a way to transcend spoken language. At first glance, sheep's wool appears soft, but it is, in reality, fairly coarse to the touch. It also happens to be one of the most resilient natural fibres.

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the artist

Resting After Fullness

2023, sculpture by Camilla Dilshat

Dilshat is interested in dualities – connection and disconnection, bodily comfort and discomfort, and how these intertwine. In her work, the body is an uncomfortable home to inhabit. In A Sinking Feeling (2023), the artist explores the co-existence of rest, discomfort and trauma in a diasporic body. The chair – a site of rest – is laden with a heavy body, its latex surface bowing under its weight, and the body is not resting comfortably as one would expect.

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the artist

A Sinking Feeling

2023, sculpture by Camilla Dilshat

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the artist

I work at not seeing you, I am tired of not being seen

2014, sculpture by Sonia E. Barrett

A desire for connection and a sense of discomfort is palpable in the work of Sonia E. Barrett, who is interested in history, with a focus on Britain and the British cultural landscape. Through her practice, she asks: 'how can we know each other in meaningful ways?' I work at not seeing you, I am tired of not being seen (2014) considers class and the subdivisions amongst labourers, and is inspired by the artist's early experiences of encountering other Black people at work. The piece consists of four pairs of feet: one tiny pair holds a mirror up, whilst the second pair is at rest. The tiny feet underneath the mirror easily go unnoticed, emphasising how labour hierarchies render certain people invisible.

Barrett notes: 'I am obsessed with bodies and locating the body in the crime scene of menial labour. I am fascinated by the lack of drama and the lack of climax in these crimes. In many ways, the true horror is their normative continuum.'

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the artist

Telling Time

2019, sculpture by Sonia E. Barrett

Telling Time (2019) is concerned with the bodies of humans, animals and trees. In the work, cross sections of 'tree limbs' operate as clock faces; indeed, it is well-known that you can count the growth rings on a tree trunk to decipher its age. Here, Barrett points to the characteristics and qualities that humans and trees share. For instance, in spoken language, the central part of a human body is referred to as a 'trunk', and the language of woodworking makes reference to human anatomy – there is the 'butt', 'tongue and groove' and 'half lap' joint.

© the artist. Image credit: courtesy of the artist

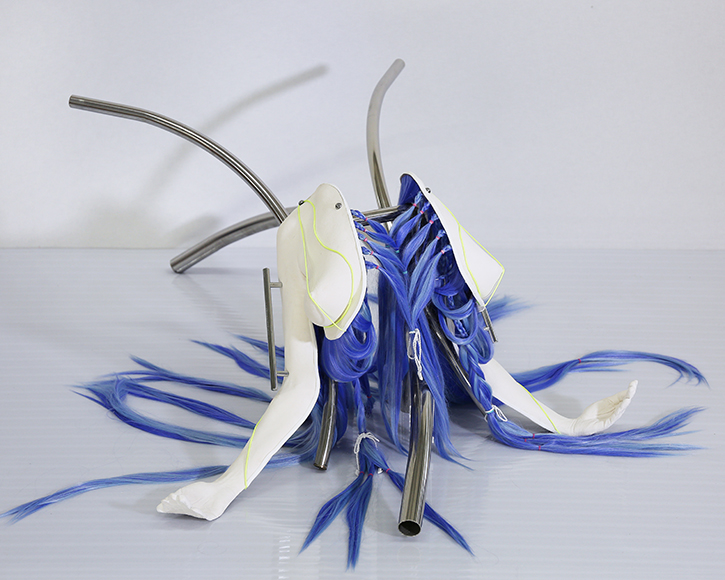

Garment 2

2023, sculpture by Ahyeon Ryu

Moving from labour to leisure, Ahyeon Ryu's futuristic installation incarnates the experience of entering a luxury shop, juxtaposing the ways in which the body is transformed into a commodity in a consumerist society. The installation conjures a relationship between the audience, artist and object, in which the audience are active participants and consumers of the bodily image. In Garment 2 (2023), the artist presents the upper torso of a body, its breasts exposed and arms laid out across the floor. However, this body is split open, seemingly vivisected, to reveal blue hair – a hark to popular culture and anime – in the place of ribs.

Hair – an often-loaded symbol in visual art, suggesting idealised female beauty, health and fertility – takes on a different life here. Its substitution for something so concealed and unseeable renders it wholly uncanny. The highly inorganic 'cyborg' colours – such as synthetic blue and neon highlighter yellow – in Ryu's works enhance the strangeness of the commodified, hyper-sexualised bodies.

© the artist. Image credit: Christabel Beddoes

Asoebi

sculpture by Sokari Douglas Camp (b.1958)

As Audre Lorde notes, 'As women, we have come to distrust that power which rises from our deepest and nonrational knowledge. We have been warned against it all our lives by the male world.'

Our bodies are the vessels through which we experience the entirety of the world. They are also fragile things, prone to illness, injury, ageing and eventually, expiration. But despite these heavy burdens, within them lies great resilience and strength. The artists in this exhibition delve deep to interrogate their experiences of the embodied self, using the body to grapple with (dis)connection, otherness, and the parallel need for resistance and rest.

The body is a powerful investigative tool, its conscious engagement a decolonial practice. So often, in order to move forwards, we need to look back, from where we have come. Similarly, to heal collective wounds, we must start with our selves. We must begin with the body.

Melissa Baksh, art historian, freelance writer, and Gallery and Exhibitions Officer at Morley College London

The exhibition 'embodied', curated by Melissa Baksh, is at the Morley Gallery until 28th October 2023. Sokari Douglas Camp's Asoebi installation will be in situ outside Morley Gallery in the community garden until 15th November 2023

Further reading

Rosalyn Driscoll, The Sensing Body in the Visual Arts: Making and Experiencing Sculpture, Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020

Audre Lorde, 'Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power', 1978

Resmaa Menakem, My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies, Central Recovery Press, 2017

!['Phoebe Boswell: A Tree Says [In These Boughs The World Rustles]' at Orleans House Gallery](https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/w800h800/artuk_stories/boswell753x1000-edited-thumb-1.jpg)