In December 1542, Mary Stuart – daughter of James V of Scotland and the French noblewoman Mary of Guise – ascended the throne aged just six days, following the untimely death of her father.

Fascination with the Catholic queen and her dramatic life has endured for nearly 500 years since, with depictions spanning visual art, theatre and literature, as well as contemporary popular culture. These many and varied depictions of Mary serve to illuminate her tumultuous life and grisly death, but also leave many questions unanswered.

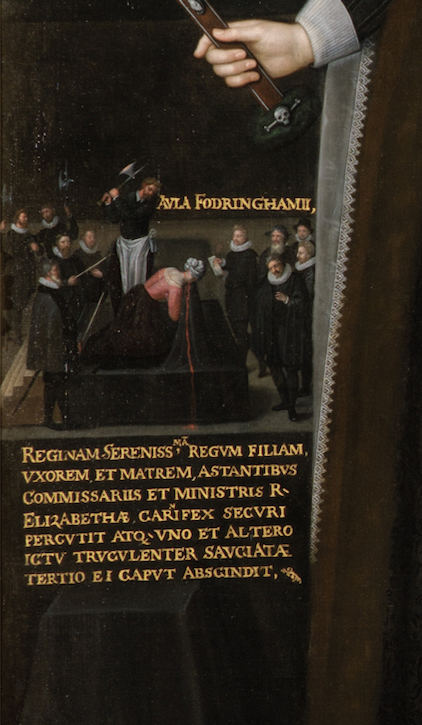

Take, for example, The Mary, Queen of Scots Memorial Portrait (as it is often known), which is in the collection of Blairs Museum in Aberdeen. This portrait, from around the beginning of the seventeenth century, is painted in the Flemish style, characterised by the use of oil paints and careful, realistic depiction of the subject matter.

It shows Mary on the morning she died – 8th February 1587 – when she was executed by three strokes of the axe at Fotheringhay Castle in England. Here, the artist depicts Mary in a black dress, indicating her status as a martyr for her Catholic faith, which was a constant source of both comfort and conflict throughout her life.

On the left of the painting is a graphic depiction of the actual execution, with Mary in a blood-red bodice, reflecting the violence of her final moments. Look closely at the detail below and you can see the three strikes that ended her life – two wounds on her neck with the axe raised to deliver the final, deadly blow.

Image credit: Blairs Museum

Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587)

(detail), c.1600, oil on canvas by Flemish School

The juxtaposition between Mary as regal and pious in the centre of the portrait and the small, sad figure at the left, stripped to her undergarments and forced to kneel at the executioner's block, is as striking for modern audiences as it would have been in the seventeenth century.

So how did this unusual portrait come to be? Despite the popularity of Mary's story today, during her own lifetime she was a controversial figure, both lauded and loathed depending on who you asked.

Mary spent her childhood in France, marrying François, the French dauphin, in 1558. He became king in 1559, but died the following year, leaving Mary to return to her native Scotland, a land gripped by religious and political turmoil. In the early years of her reign, she re-established the power of the monarchy and its finances but she had yet to win over the Scottish people.

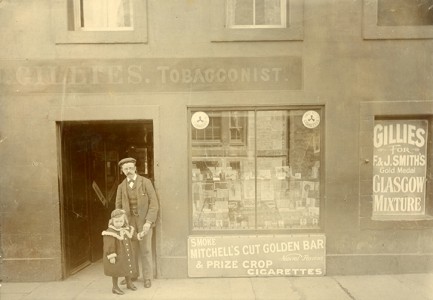

Image credit: National Trust Images

François Clouet (c.1515–1572) (after)

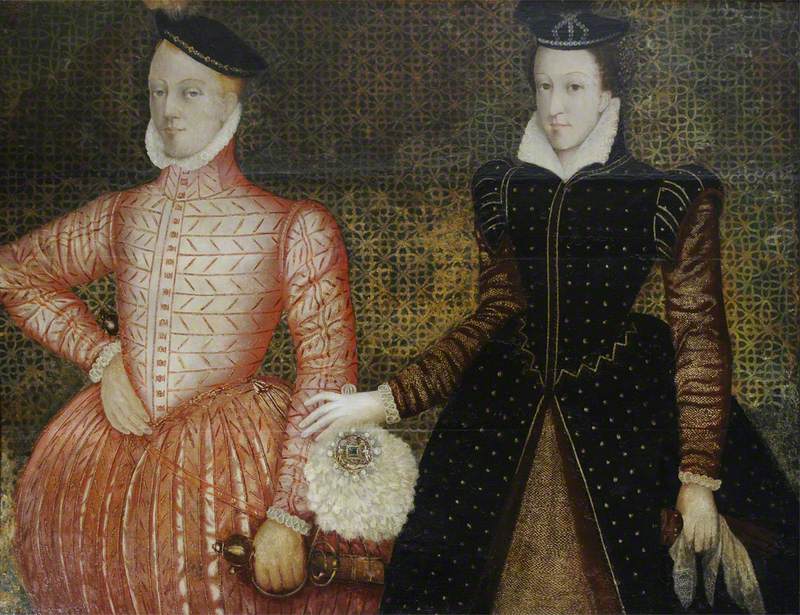

National Trust, Anglesey AbbeyIn 1565, Mary was married again, this time to her cousin, Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, and gave birth to her son and heir, James (later James VI and I) in 1566. A year later, her husband died under suspicious circumstances.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Henry Stuart (1545–1567), Lord Darnley, and Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587) c.1565

British (Scottish) School

National Trust, Hardwick HallControversy seemed to follow the queen as, just three months later, she entered into her third marriage with James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, who had been accused and acquitted of murdering Lord Darnley. Unsurprisingly, Mary was deeply unpopular following these events, and was imprisoned by her own noblemen before being forced to abdicate in favour of her infant son.

Mary's solution to this turn of events was to flee to England, in the hope that her cousin, Elizabeth I, would protect her. Instead, she was seen as a threat to the English throne and placed under house arrest. She was held in captivity for 19 years, abandoned by her country and her family.

Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587), at Fotheringhay c.1929

John Duncan (1866–1945)

Tullie House Museum and Art GalleryHer only comforts during these lonely years were her ever-present Catholic faith and her two loyal ladies-in-waiting, Jane Kennedy and Elizabeth Curle (both of whom are depicted on the right of the memorial portrait, as well as in the painting above).

As a gesture of gratitude, Mary gifted a miniature portrait of herself to Curle shortly before her death. Curle then travelled to Europe, where she commissioned the memorial portrait in Antwerp. The artist used the miniature to capture Mary's likeness.

Another fascinating object in the Blairs Museum collection, The Blairs Jewel, has possible links to The Mary, Queen of Scots Memorial Portrait. If you look closely at the features in the Jewel and the painting, the way in which the two artists have captured her expression – with a high forehead and curly red hair – are strikingly similar.

Perhaps they were working from the same original miniature, making a direct link between the two objects. The Blairs Jewel, also known as a reliquary, is unusual in that this secular portrait has been presented as a relic, surrounded by the names of female saints inscribed in gold lettering. A reliquary is normally used to house objects relating to saints and martyrs, such as bones or clothing. The exact history of this object remains shrouded in mystery.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Mary (1542–1587), Queen of Scots, Reigned 1542–1567 c.1610–1615

unknown artist

National Galleries of ScotlandThis is not the only example of the 'cult' of Mary, Queen of Scots, which grew in the years following her death. Shortly after the memorial portrait was unveiled, illustrations, engravings and paintings of Mary's likeness began appearing all over Europe, such as a large-scale portrait held by the National Galleries of Scotland, above, also said to have been based on a miniature, and the rather graphic Head of Mary, Queen of Scots after Decollation, below, currently held at Abbotsford House.

Image credit: Abbotsford, The Home of Sir Walter Scott

Head of Mary Queen of Scots after Decollation 1587

Amos Cawood

Abbotsford, The Home of Sir Walter ScottThe imagining of Mary's final moments continued into the nineteenth century, a focus for leading Pre-Raphaelite artist Ford Madox Brown in his emotionally charged Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, featuring fainting ladies-in-waiting, and Mary's royal mantle shown dramatically cast to the floor.

Image credit: The Whitworth, The University of Manchester

Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots 1839–1841

Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893)

The Whitworth, The University of ManchesterAnother portrait at Blairs Museum featuring Mary is the Mary Stuart painting, which depicts the queen as a young woman of around 21 years of age.

During her life, before she was suspected of plotting to murder her husband and forced to flee her own country, she was described as pretty and graceful, shown here through her fair skin and delicate features.

Little is known about this painting, other than it appears to be a seventeenth-century copy of a contemporary portrait that has now been lost. One clue can be found by looking closely at her hands.

Mary does not wear a wedding ring, meaning that it should date from before her marriage to the dauphin of France in 1558. However, it could be that her ring was painted out, as the dauphin died shortly after they were wed.

Image credit: Blairs Museum

Mary, Queen of Scots (1542–1587)

(detail), 17th C, oil on canvas by unknown artist

Her gown is depicted in elaborate and careful detail, especially in the lace at her wrists and neck, as well as the jewels on her belt. Contrast this with the drapery behind her, with visible brushstrokes and simplistic fleur-de-lis motifs in the corners. It is possible that the background was painted out as well, in an attempt to turn what was once a portrait for her first husband into one for her husband-to-be, Lord Darnley.

Another interesting French connection in this work is the spelling out of her name in gold letters, 'MARIE STUART'. For nearly 200 years prior, the powerful Stewart family, Mary's forebears, had ruled over Scotland. It was Mary, shipped off to France at the age of five, who changed the spelling of the family name from Stewart to Stuart. This made it easier for French speakers to pronounce and was possibly an attempt to endear herself to her to the French court, her home for 13 years.

Mary, Queen of Scots' depiction in visual art helps us to understand her relationship with faith, family, and the world she lived in. It is precisely the fact that she encompasses so many different identities – from 'martyr' to 'mother' and even 'traitor' – that makes her so interesting to us today.

Caitlin Jamison, museum volunteer