'Fixed in the memory, a rich seam of strife and suffering, sudden death, choking disease, degradation and dignity.'

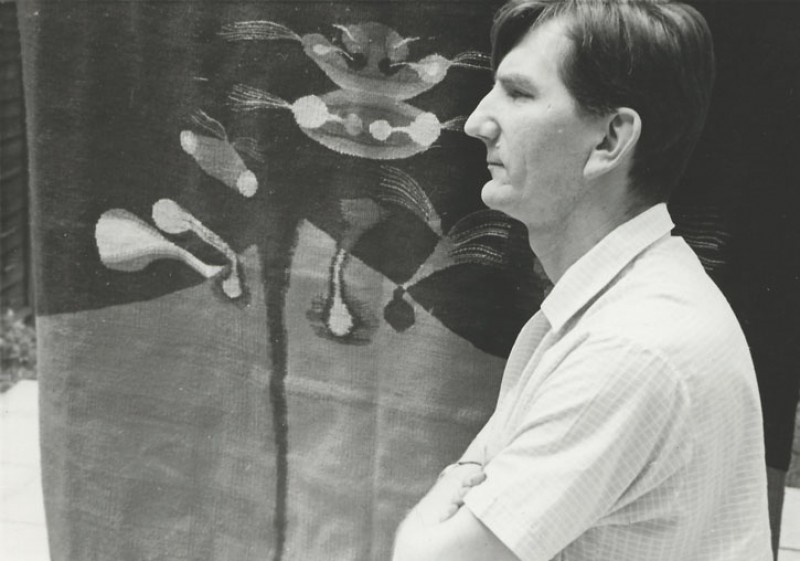

This introduction – from a 1979 documentary (Kane on Friday) about the Welsh artist Nicholas Evans – aptly describes the body of work produced by the ex-miner over a 26-year period.

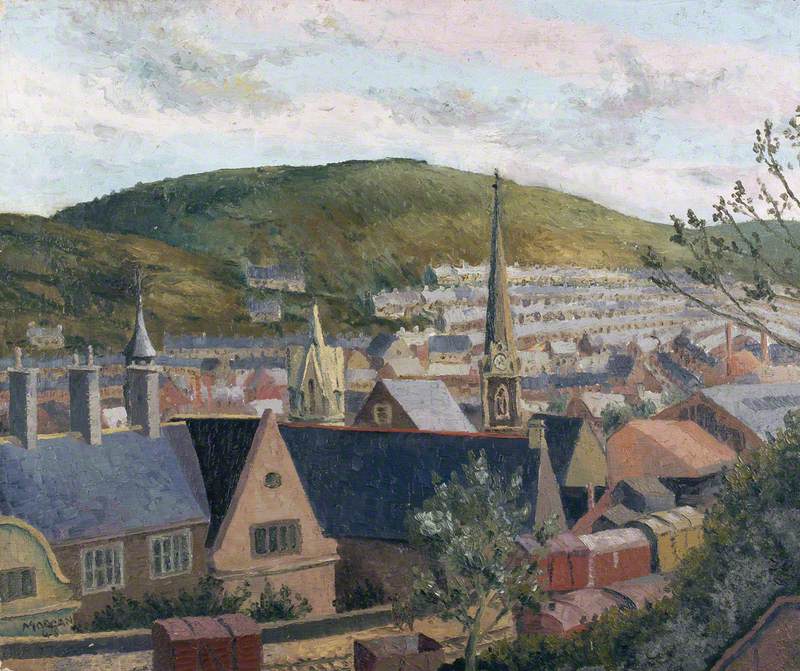

Born in 1907 in Aberdare, Nicholas Evans was brought up in the centre of a close-knit mining community. It was a community that, right up until his death in 2004, he sought to portray in art, with a truth that often verged on the dramatic, but which was always painted with a deep love for the people he knew.

Nicholas Evans' father was a collier and his mother had been a pit girl. Evans, himself, began in the tradition of the mining community he hailed from at the age of 14. Sadly, two years later, his father was killed at Fforchaman Colliery. As was the custom, he was brought home and laid on the kitchen table.

Evans never forgot the moment when he saw his father's return from his bedroom window. This was a turning point for Evans, for there had been many deaths in his family and the closely acquainted neighbourhood he belonged to. In respect of his mother's wishes, Evans left the mining work that he loved and became an engine driver for Great Western Railways, but he always longed for the mines. To him, they were in his blood and in his soul.

For the rest of his working life, Nicholas Evans continued to live and work amongst the mines and its people but his move into art did not come about until he was nearing retirement. It was only now that Evans began to pour onto the hardboard, that he primed with emulsion, his remembrances and his admiration for the industry.

Painting black and blue oils with his fingers and rags, Nick Evans, as he styled himself, instinctively knew what he wanted to show the world: his passion for the working man, with empathy rather than sentimentality. When describing his technique, Evans explained that he was aware that some of the great artists – such as Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci – all painted with their fingers. He equated the technique to playing the piano, explaining 'there is such joy in it.'

A grant from the Arts Council of £1,000 allowed Evans to make a significant outpouring of paintings that led to a one-man show at Oriel Gallery in Cardiff in 1978. The success of this show took him to London and to Browse & Darby, where Lawrence Gowing, Principal of the Slade School of Art, saw his work: 'I was aware we were in the presence of a very uncommon thing… deeply appealing and responsive to the condition of life of the ordinary people.' When Evans saw his name on the window of the gallery, he wept. Here was someone without a single art lesson to his name exhibiting in a London gallery.

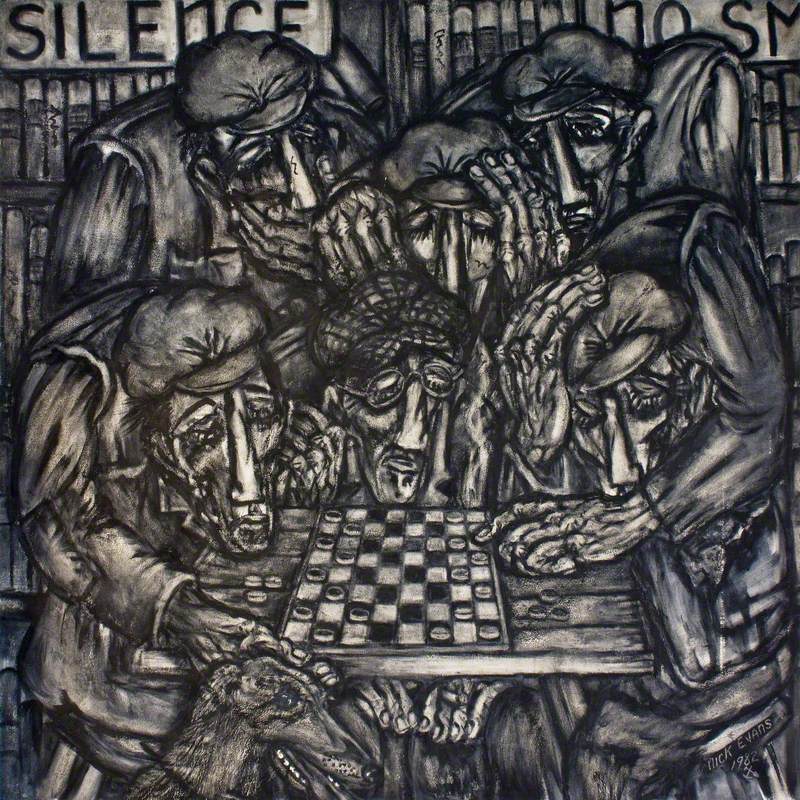

In the 1979 interview, Vincent Kane said that when he looked into the paintings, he saw 'death and suffering and disillusion' and asked Evans if he felt the same. He agreed but added, 'The comradeship I think outweighs it all. The friends who would come to help you if you needed it. I never found that anywhere else, only in the mines.'

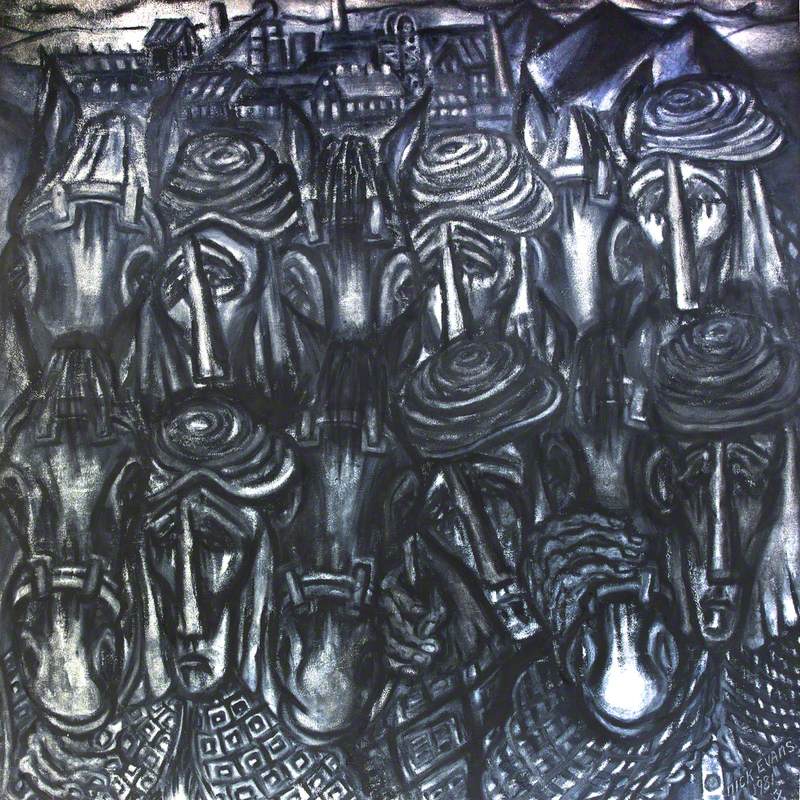

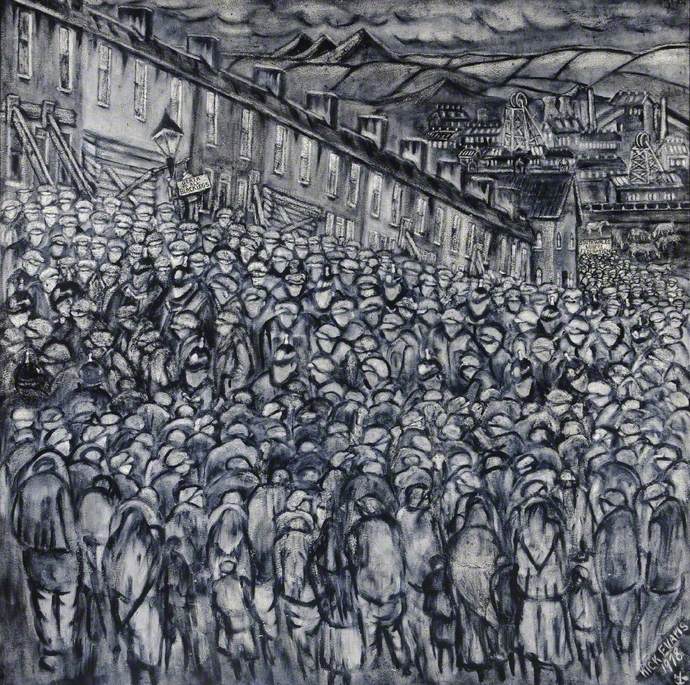

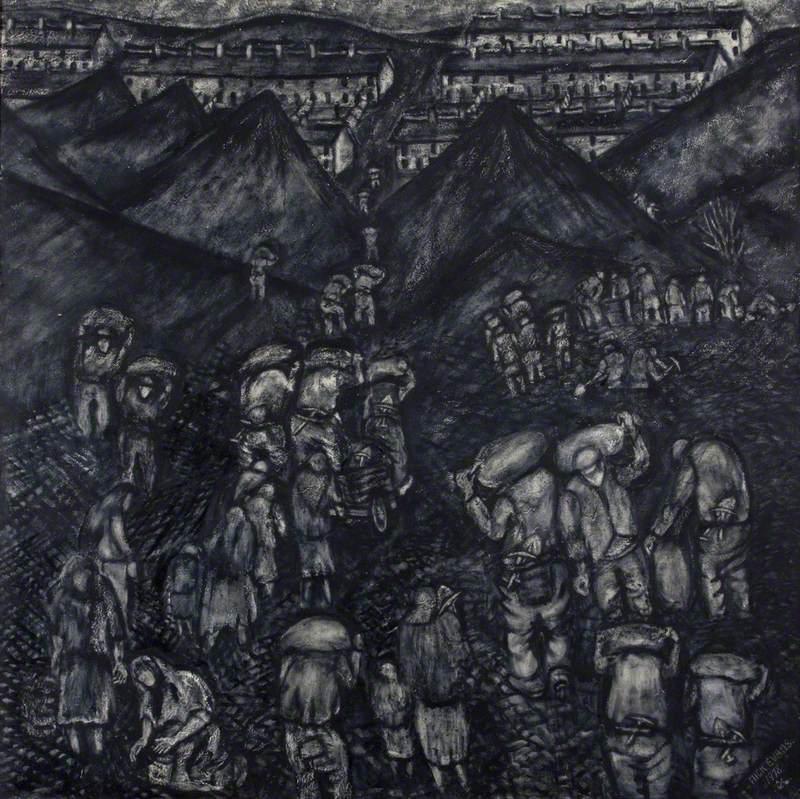

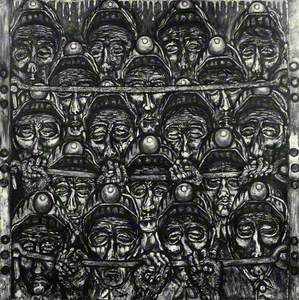

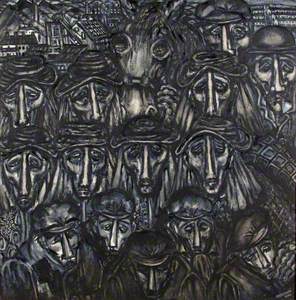

Pit Closure, Miners Coming Up 1977

Nicholas Evans (1907–2004)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru / The National Library of WalesAs he painted, Evans would start with a face, and he would talk to that face as if they were old friends. One idea would lead to the next and his hands would work frantically across the canvas, bringing these people and their stories to life. Stark and sombre, the canvases that came, one after the other, revealed many aspects of the mining community at work and at play. When surveying the huge body of work he created, he classed himself as 'The Miner's Historian' – an epithet that perfectly describes his output.

Life in the mines

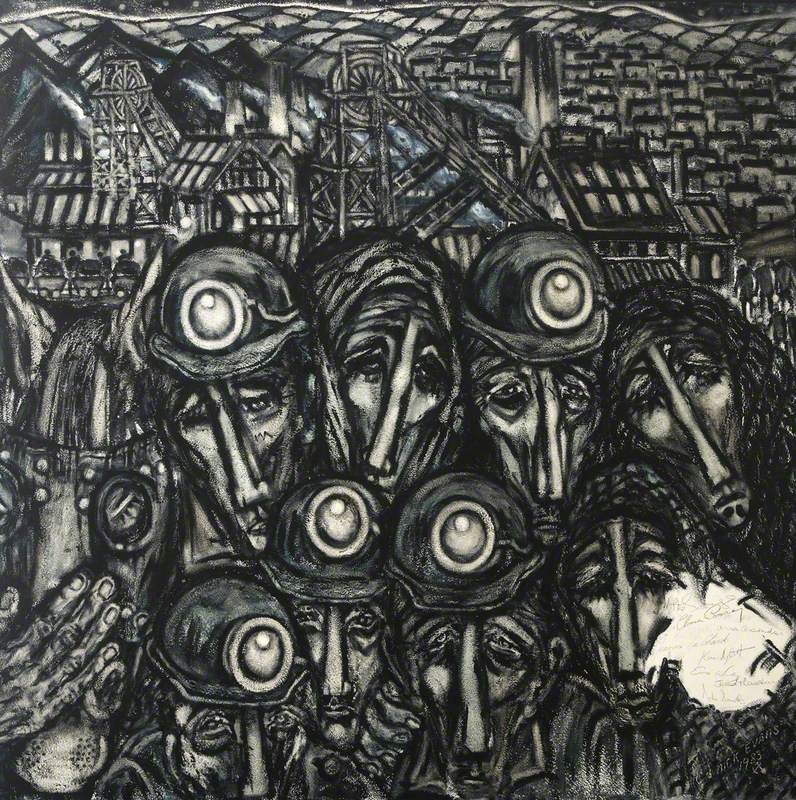

Many of Evans' works show the daily life of the mine. In Coming to the Surface, the men are cramped together in the cage that returns them to the surface after a day of toiling at the coal face. Their Davy Lamps are empty, and the pit helmet lights are now diminished. Tiredness is etched across the faces of the men as they look out at the viewer. This is a hard life, there is no question about that.

In his poem, Shaft, Sam Cairns describes what being inside the lift was like:

Within this metal cage

men are momentarily trapped

their lives and their families livelihoods

hang by the strength of ropes

tensility of the steely prison-like structure

skills of its makers

and mastery of the winder operator. They are all trusted

as are the nuts and bolts holding them together.

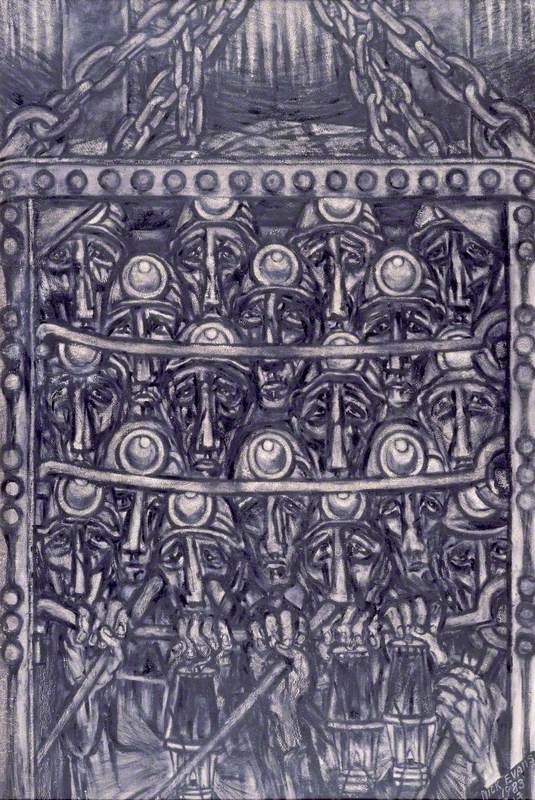

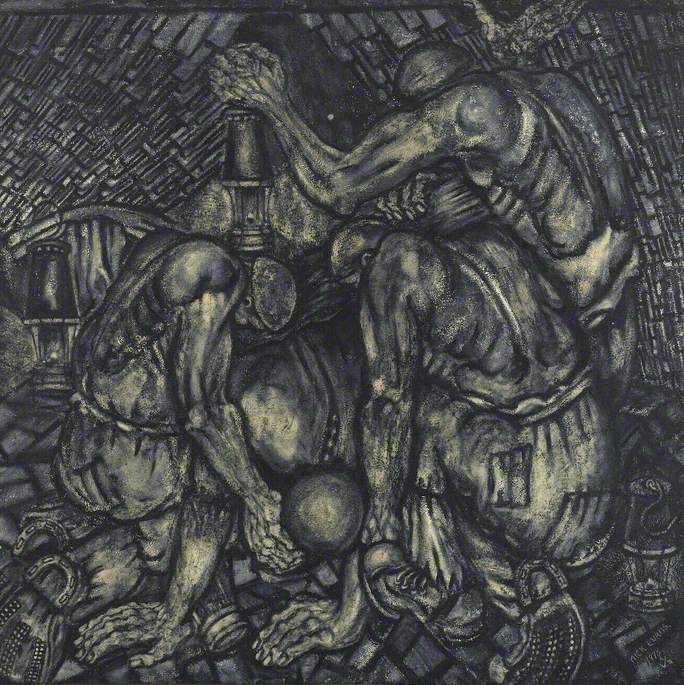

Unless you have experienced this working life, it is hard to imagine being so far underground, but in Claustrophobia, Evans takes us right into the heart of the experience. The contorted bodies are crammed into the smallest of spaces from the moment they step into the cage that takes them down the shaft. Evans saw the miner as a heroic figure, but there is no romantic viewpoint shown here. The men are shown grappling to find some space of their own, skeletal hands digging away. You can almost imagine that this work has been created out of the coal dust that coated their bodies.

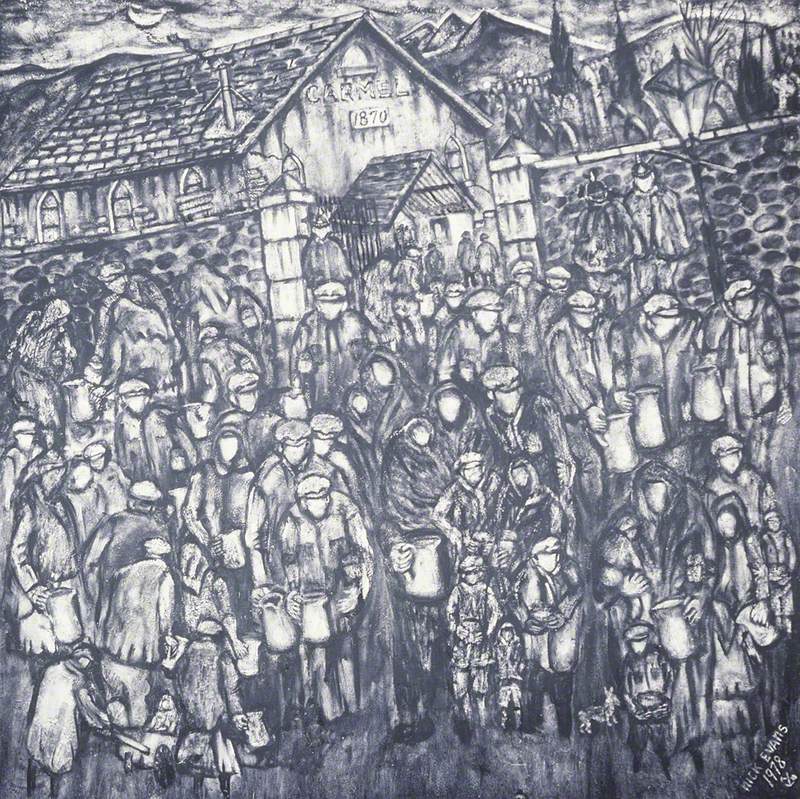

Colliery closures were an ever-present threat, and the mining unions would fight with strike action. In Hunger Marchers (1977) and Coal Pickers During Strike (1978), Evans revealed the difficulties that communities faced. Rhoda Evans, the artist's daughter, described what life was like in her 1987 book: 'The Miners' homes were cold and draughty. Many, with their families, visited the slag tip to grub for scraps of coal during strikes. These sites had been dug over, and over again during previous strikes. They yielded up but a small return for much labour. Even old pieces of wood, anything that would burn, were acceptable.'

The dangers of mining

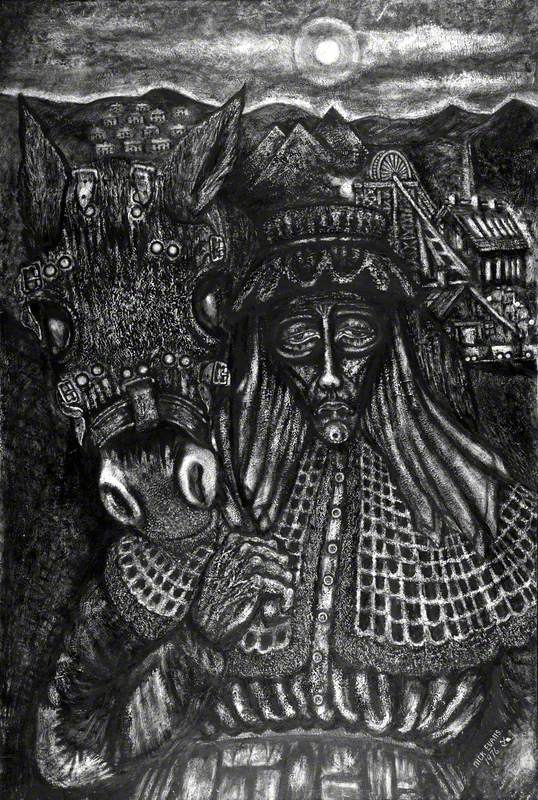

Nick Evans knew first-hand of the dangers of mining after the death of his father in 1923. Coming from a religious family, his father's death brought him closer to one of his colleagues, known as 'Dai Pentecostal'. Dai would sing as he hewed at the coal face and the young Nick would join in, eventually becoming a lay preacher himself.

In many of his works, he brings the imagery of Christianity to the mining community. Here, a collapsed mine has trapped the workers who huddle together unsure of their fate. Christ appears as the light of the earth, dressed as a miner and his outstretched arms protect the men while his golden keys show them the way forward. Rhoda Evans spoke of men being 'born again' underground: 'They were digging coal for the glory of God. They could be classified among the best workers and did their jobs as an act of worship.'

© the artist's estate. Image credit: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Entombed – Jesus in the Midst 1974

Nicholas Evans (1907–2004)

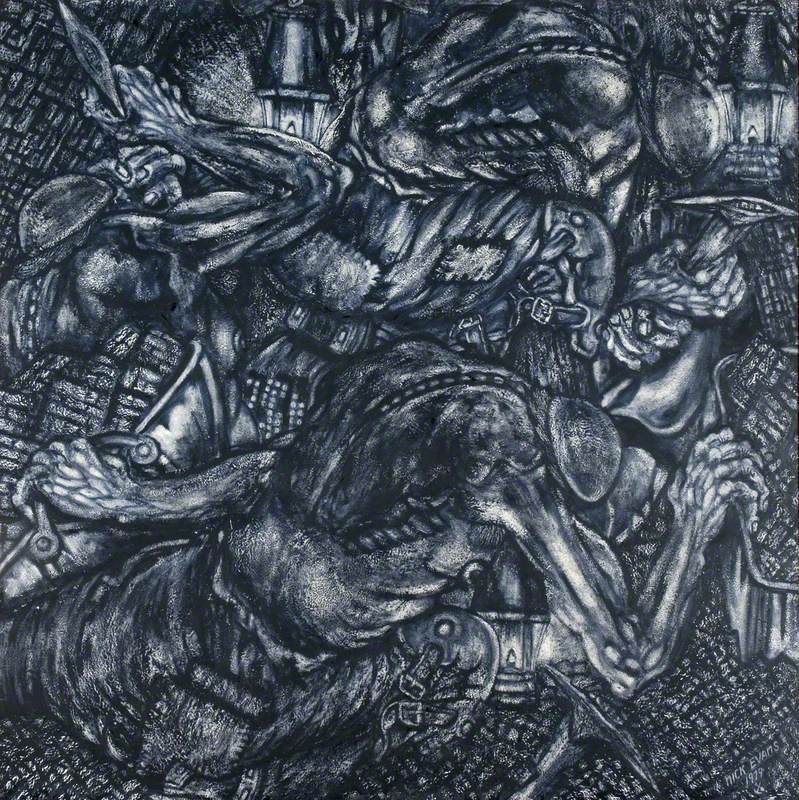

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum WalesDisasters were not confined to the mines: they could affect a whole community. In Aberfan (1979), Evans does not shirk from sharing the trauma and heartbreak that the disaster brought to the village on 21st October 1966. The spoil tip, built up over years, came down the mountainside as slurry, engulfing the houses and, most tragically, the Pantglas Junior School; 116 children and 28 adults died on that terrible day.

In Evans' painting, we see the grieving families huddled together, their hands covering their faces in their despair. One holds a swaddled baby close, as if afraid that it too will be ripped from their grasp. The tiny coffins are a heart-breaking reminder of the loss of so many young lives.

Women's role in the mines

One of Evans' earliest paintings was Women Working Windlass (Pit Top), made in 1978. In this work, Evans paid tribute to the women who worked on the surface and who are often forgotten in the history of mining. From 1842, while women were no longer working underground, their work at the pit top was vital: hauling the coal to the surface, loading it onto wagons and then sorting it. As time went by, the roles undertaken by women were given over to the men who had been injured in accidents.

Later, in his 1990 painting My Mother was a Pit Girl, Evans showed the women wearing hats to add a little femininity to their attire. As Rhoda Evans said, 'We should remember that although they worked as men, and in a dirty industry, they still retained their womanly pride.'

Fifty years separated Nick Evans from his mining experiences and his decision to express, in art, all of the thoughts and feelings he had about the life of the miner. He had continued to paint into his 90s and his last exhibition, 'In His Oils', was held at the Rhondda Heritage Park, fittingly on the site of a former mine, in March 2001.

There is no doubting the power behind his works. When asked about his legacy, Nick Evans said: 'I intend my pictures to arrest you. You can go to a picture gallery and pass pictures of lovely flowers, or a vase of daisies, or some trees. I'm hoping that when you come upon a painting I have done, you will stop.'

Wendy Gray, writer and teacher

Further reading

Sam Cairns, The Hearts Live On, acepub, 2014

Rhoda Evans, Symphonies in Black The Paintings of Nicholas Evans, Y Lolfa Cyf, 1987