Yinka Shonibare CBE has stood at the forefront of contemporary British art for the past few decades.

From his fourth-plinth installation Nelson's Ship in a Bottle in Trafalgar Square to his signature headless mannequins clothed in Dutch wax batik fabric, his works powerfully examine the interrelationship between identity, race and colonial history in a globalised world.

We are proud that Shonibare is Art UK's 2019 Patron. To celebrate our collaboration, I interviewed him about the evolution of his work, his views on public sculpture, and his concerns for the future.

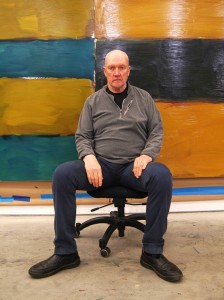

Born in London in 1962, Shonibare moved to Lagos, Nigeria with his family at the age of three. He remained there until the age of 17, when he decided to return to London to pursue an art degree.

He went on to study Fine Art at Central Saint Martins (formerly known as the Byam Shaw School of Art) and then at Goldsmiths, University of London, where he received an MFA in 1991.

As a young art student, Shonibare found himself drawn to sculptural forms rather than painting. Though he admits, 'I never intended to become a 'sculptor'.'

In fact, Shonibare has experimented with many mediums, from video, photography to performance work.

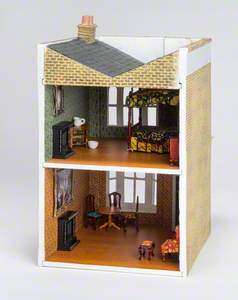

He has perfected the art of the diorama – uncanny installations that appear to be taken directly from a theatre production or stage set.

'I see all of the art forms as connected, and I have never isolated sculpture from other mediums.'

While he deploys colourful fabrics that are rooted in colonial trade and history, the common thread running through all of his work is a subversive approach to art history, ironic wit and baroque theatricalism.

What were the influences of his practice?

Emerging on the art scene in the 1990s – the same time as the Young British Artists (YBAs) – Shonibare's early practice shared an openness for unconventional mediums and materials.

'My work has always incorporated fashion, textiles and popular culture.'

Unconcerned with following in the footsteps of British modern artists, Shonibare took his own path.

'I was not taking influence from the sculptural practices of Henry Moore or Barbara Hepworth... nor even my closer contemporaries at Lisson Gallery like Richard Long or Richard Deacon.'

His sculptural works departed radically from previous forms and he took influence from postmodern and contemporary critical theory.

'My practice has always been rooted in postcolonial and deconstructive theory; the texts of Edward Said and Jacques Derrida.'

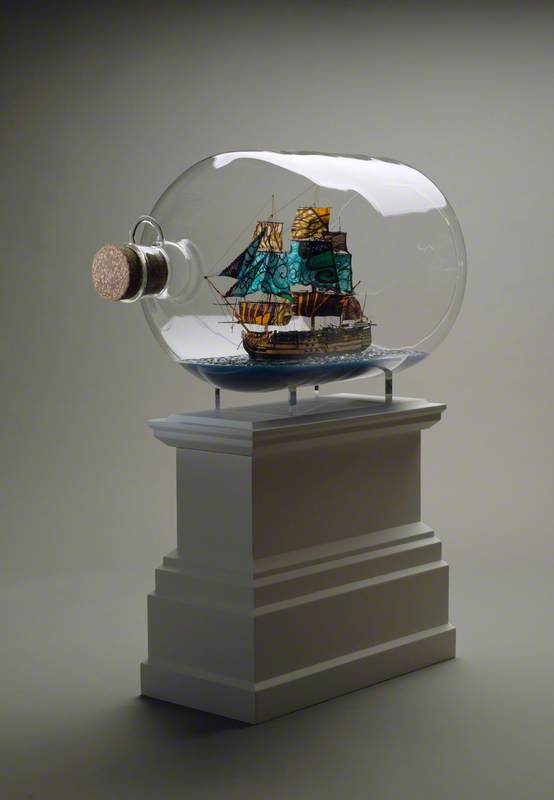

Nelson's Ship in a Bottle

by Yinka Shonibare (b.1962)

The desire to subvert art historical traditions is integral to Shonibare's practice, not only for aesthetic reasons, but political ones. He notes, 'as a medium, sculpture has always been more closely associated with the elite.'

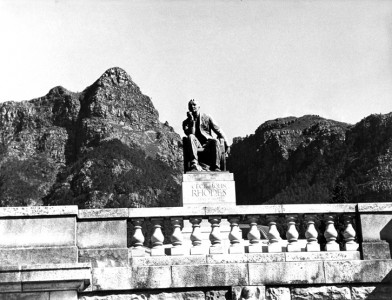

As it happens, out of nearly 9,000 records of public sculpture currently on Art UK (there are many more to arrive), a significant proportion of the artworks reflect individuals and bodies of (white) power – the church, the monarchy or the government.

He continues: 'It is so incredibly important for these works to be digitised and no longer solely in elite spaces. This means they can reach a wider audience alongside helpful contextual information.'

'My work deconstructs the grand narratives rooted in the history of power and empire. I aim to look at those traditional icons and dismantle that power.'

This incentive is most visible in Nelson's Ship in a Bottle, commissioned to appear on Trafalgar Square's Fourth Plinth. Significantly, the work was the first time a black British artist was chosen for this public sculpture commission. The site-specific installation responded to its immediate surroundings – Nelson's Column and the square itself – both created to commemorate Nelson's victory at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805.

'The ship is a scaled-down version of the HMS Victory, the ship captained by Nelson... but the sails are made from African textiles.'

A postcolonial twist on conventional British public monuments, Shonibare explains: 'I wanted to represent what Britain is like today, using Nelson as a symbol.'

But Shonibare's practice is also about deconstructing the dominant narratives of art history, namely the Eurocentric aesthetic traditions underpinning modernism.

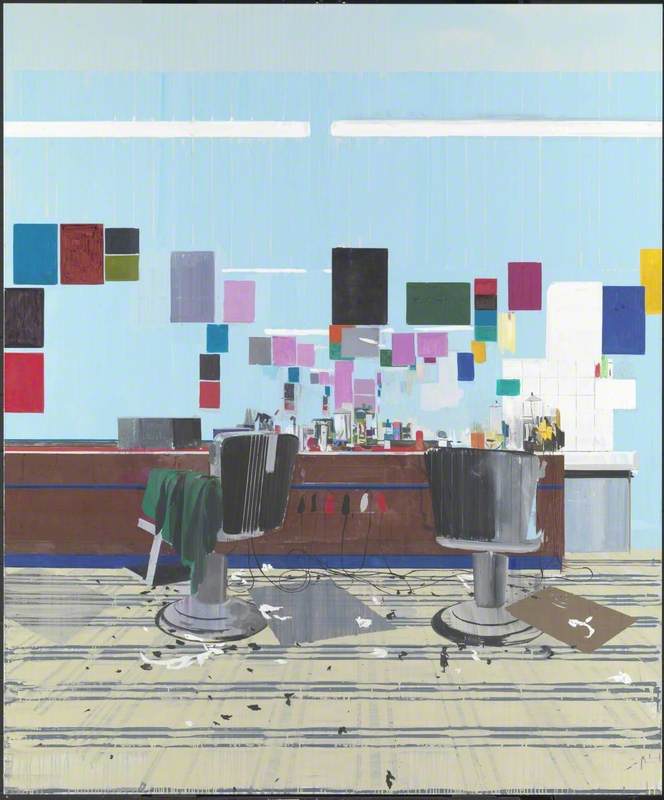

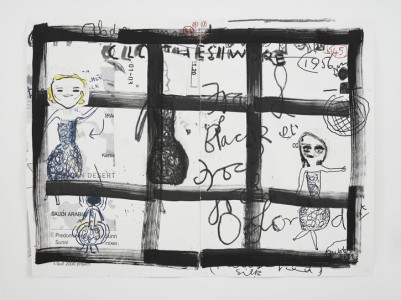

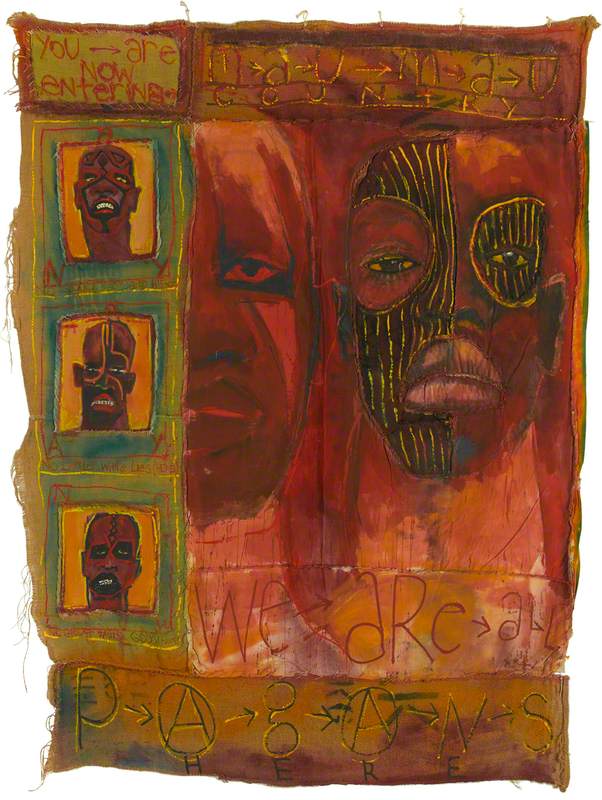

In 2003, Shonibare debuted the work Line Painting commissioned by the Arts Council. He explains that the work was about 'reproaching modernism, in particular, the doctrines of American art critic Clement Greenberg.'

Published in 1960, Greenberg's influential essay 'Modernist Painting' had praised the work of the American Abstract Expressionists, and advocated a form of flattened, autonomous and self-reflexive painting.

Imitating the abstract style of mid-century painting, Line Painting acknowledged yet subverted Greenberg's formalist approach to painting. Shonibare explains:

'The work went against Greenberg's teaching that art should be autonomous, or follow the doctrine of 'art for art's sake'.'

In a gesture of playful irony, Line Painting introduced elements of the external world through the use of Dutch wax fabric. An inherently political gesture and a form of institutional critique, Line Painting pointed to a dimension beyond the intellectual parameters of the museum.

A question on the artist's mind was: 'How can I bring something from Brixton market into the gallery?'

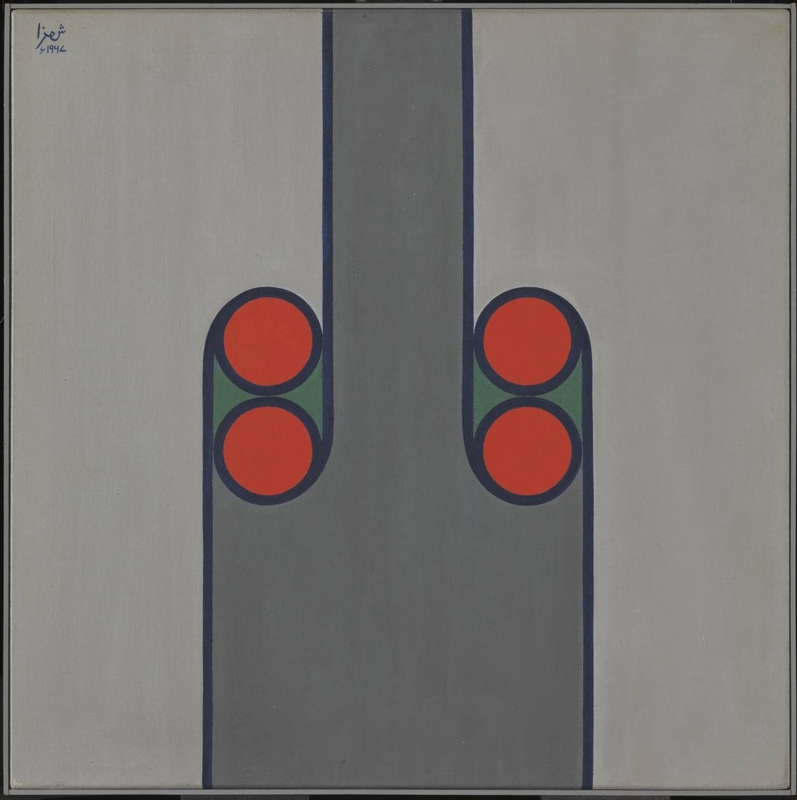

Wind Sculpture VI

by Yinka Shonibare (b.1962)

Shonibare's signature colourful fabrics have a complicated historic import.

'African' or Dutch wax prints, originally stemmed from the process of Indonesian batik (a wax-based technique), which was later industrialised by the Dutch colonisers. By the 1880s, the fabric travelled on Scottish and Dutch trading ships to West Africa, where it became a symbol of identity and independence by the 1960s. Finally, the textiles returned to post-war Britain during the time of immigration.

A poignant reflection upon our hybridised culture, Shonibare's work powerfully communicated that 'Britishness' is inseparable from its colonial past.

'I didn't want my sculpture to look unapproachable. It needed to be something people could relate to, something that felt familiar.'

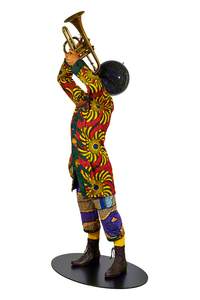

Shonibare's life-sized mannequins appear so familiar, they have an uncanny, anthropomorphic quality. Trumpet Boy uses Shonibare's trademark headless figures, a motif which he abandoned in the aftermath of horrific terrorist attacks.

Why did he create decapitated figures in the first place?

'This started as a joke about the French Revolution. In the early 1990s, I was thinking about this period of history and the guillotine. But when the terrorist attacks became more and more frequent, I decided to stop creating headless figures. It all became too macabre.'

A universal symbol, the motif of the globe 'voids the issue of identity. It prevents the work from alienating groups of people.'

He adds: 'I wanted my work to be viewed everywhere by everyone.'

Globe Head Ballerina

by Yinka Shonibare (b.1962)

So should we regard Shonibare as a 'political' artist?

'My work is not about producing or pushing some kind of ideological position,' he reflects.

'I wanted my work to deal with serious issues in a playful way... it's about providing a space for reflection. If I've already decided the outcome, there is no space for thought.'

Shonibare's brilliance lies in the fact that his art usually poses a pertinent question. He challenges the status quo rather than pushing a political dogma.

Reflecting on Nelson's Ship in a Bottle, Shonibare says, 'the work made a huge impact, partly because it divided opinion. While some people regarded it as a celebratory work, or even jingoistic, others thought it was being critical of Nelson and British history.'

Shonibare also refuses to take a simplistic and one-sided approach to Brexit, a divisive topic that has brought new relevance to much of his oeuvre.

'Human survival has always been based on compromise. There is no such thing as a 'no deal'. We will be negotiating our relationship with Europe for years.'

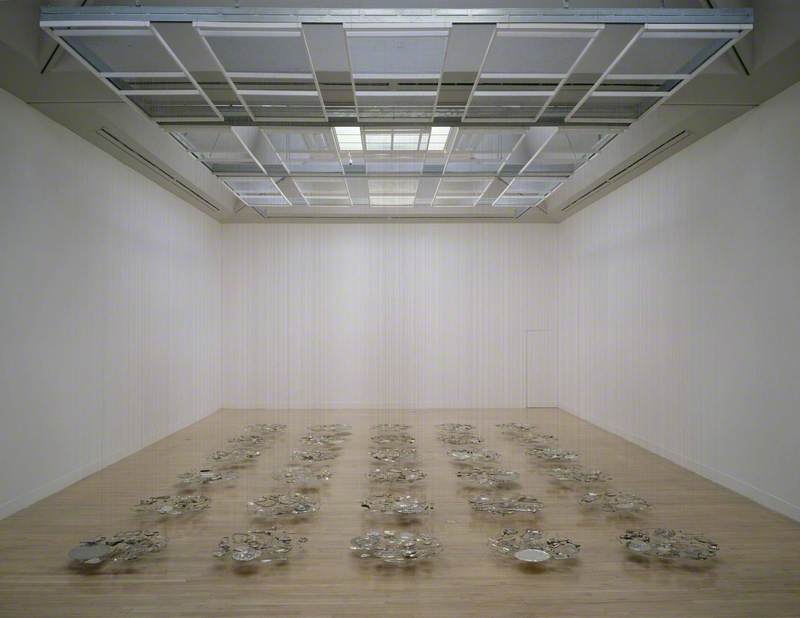

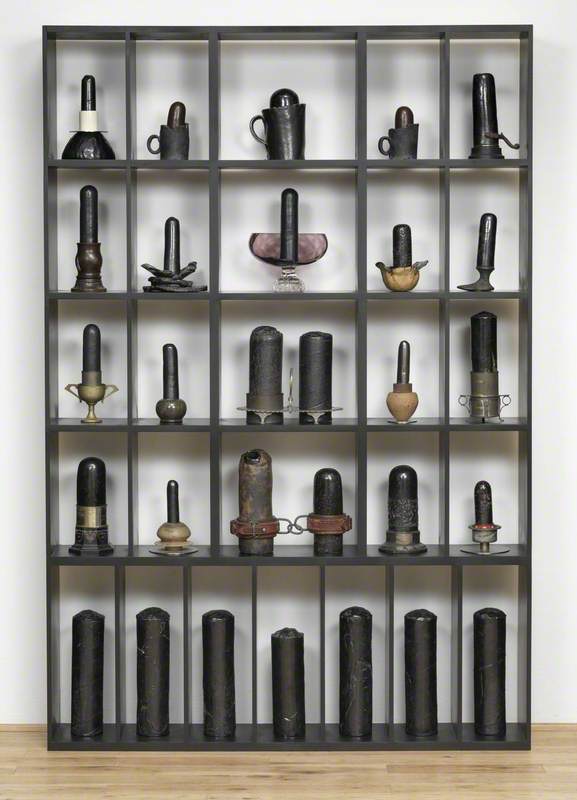

An embodiment of this inevitable historical process, End of Empire (2016) was commissioned to commemorate the centenary of the First World War and stands in Turner Contemporary, Margate.

'I wanted to make a work that could express the possibility of conflict with possible resolution. The upswing and downswing is a metaphor for this balancing act.'

End of Empire

sculpture installation by Yinka Shonibare (b.1962)

More recently, Shonibare's practice seems to have shifted.

In reaction to current global affairs, his work explores pressing political themes from the present and near future – migration, climate change and even space travel.

Since 2015, Shonibare has made three Refugee Astronaut sculptures.

First exploring the figure of the astronaut in the early 2000s, Shonibare's motif has now taken on a new significance, especially as we wait in anticipation for companies such as Elon Musk's Space X to create commercial space travel and missions to Mars.

'The figure of the astronaut was initially a simple metaphor,' he explains.

For Shonibare, the astronaut stood as a symbol of discovery and expansion into new territory. Pointing to both future explorers and historic ones, the work hints at the exploitation of foreign lands and indigenous communities.

A prophetic glimpse into a near future, Shonibare explains that, 'Refugee Astronaut points to the inevitable political questions that lie ahead of us.'

Refugee Astronaut

by Yinka Shonibare (b.1962)

What distinguishes Shonibare as an artist is his ability to collapse the political and playful – the past, present and future. His sculpture acts as a powerful paradox that shines a light on the relevance of cultural hybridity and postcolonialism.

To end our conversation we return to possibly his most iconic work, Nelson's Ship in a Bottle. I ask: how did you get that ship into the bottle?

To which Shonibare replies with a smile: 'If I told you I'd have to kill you first.'

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK