Mothers are revered as the creators and carriers of life, and mothers shown in art are often elevated to the status of sainthood – unless the mother happens to be from the African diaspora. The familiar seventeenth-century European Madonna is an image of the virginal figure of Mary, the mother of Jesus – almost always shown as a white woman, despite the fact that Mary was from Nazareth in Galilee, and was, in all probability, olive-skinned like Jesus and Joseph, as are the majority of people from that area.

Through the centuries, motherhood has been linked to an idealised white birth, as depicted in the painting The Virgin and Child with Two Angels by Liberale da Verona. In art, white motherhood was put on a pedestal and worshipped as a position of purity, self-sacrifice and virtue.

The Virgin and Child with Two Angels

probably about 1490-1510

Liberale da Verona (c.1445–c.1526)

Centuries of repeated cultural messages about the 'ideal' mother, supported by the upheld dominant white culture, continues to have an impact on how non-white mothers are viewed and treated in popular opinion and the law.

Motherhood is the root of the world. Without motherhood, human civilisation as we know it would not exist. It has been proven that human civilisation started in the African continent, yet, despite this, most canonical art images of mothers depict white women in a saintly, nurturing role, and positive images of Black motherhood are generally obscured. Black mothers were traditionally viewed as 'others', and not quite human.

Anne Davidson's 1985/1986 sculpture Woman and Child shows a traditional scene of maternal protectiveness. The protective mother is displayed as both soft and strong: she pulls her child close to her side, with her right hand an open palm around the child's back, and her left hand in a clenched fist, determined to face whatever is ahead. However, even in the late twentieth century, representations of mothers and scenes of tenderness between mothers and children from the African diaspora remained sparse in European art collections.

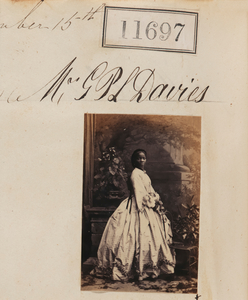

Sarah Forbes Bonetta was born a princess into a West-African Yoruba dynasty. Her parents were killed during war when she was five, and so she was captured as a state prisoner and given to Queen Victoria as a 'gift' in 1850. Queen Victoria became a distant surrogate parent for the young girl, and later a godmother to Forbes Bonetta's own daughter Victoria Davies, in whom she retained the 'warmest interest'.

Queen Victoria arranged for a series of people to care for Forbes Bonetta, arranging her education with the Church Missionary Society in Sierra Leone in 1851, and upon her return to England four years later, aged around twelve, putting her under the charge of former African missionaries Reverend James F. Schön and Mrs Anne Schön. The Schöns' house, in Chatham, Kent, was a base for several Africans in the UK.

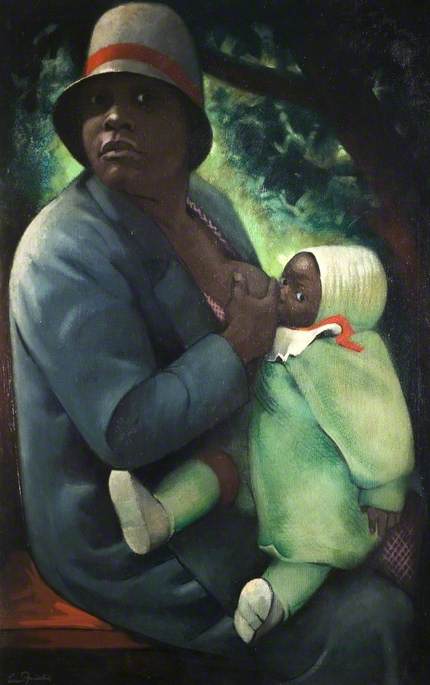

Black Mother (1931), by Bohemian painter Ernst Neuschul, portrays a mother breastfeeding her child. This portrait shows both mother and child as alert to outside influences rather than focused on the intimate act of bonding and nourishment. Neuschul's painting was created as a celebration of Black motherhood and humanity at a time when the Nazi party was forcibly sterilising African-Germans, and increasing the persecution of people of colour in Germany. Neuschul elevates the image of an oppressed figure with this work of respect and dignity.

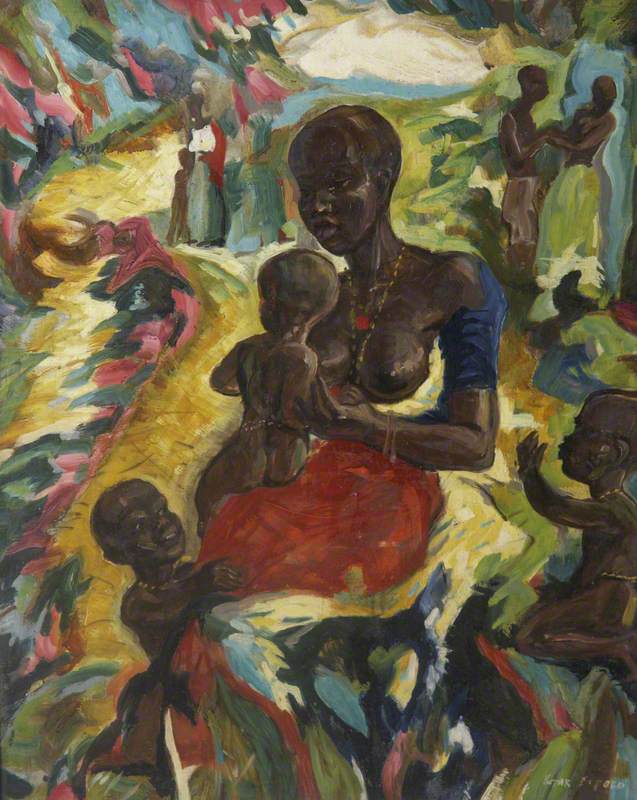

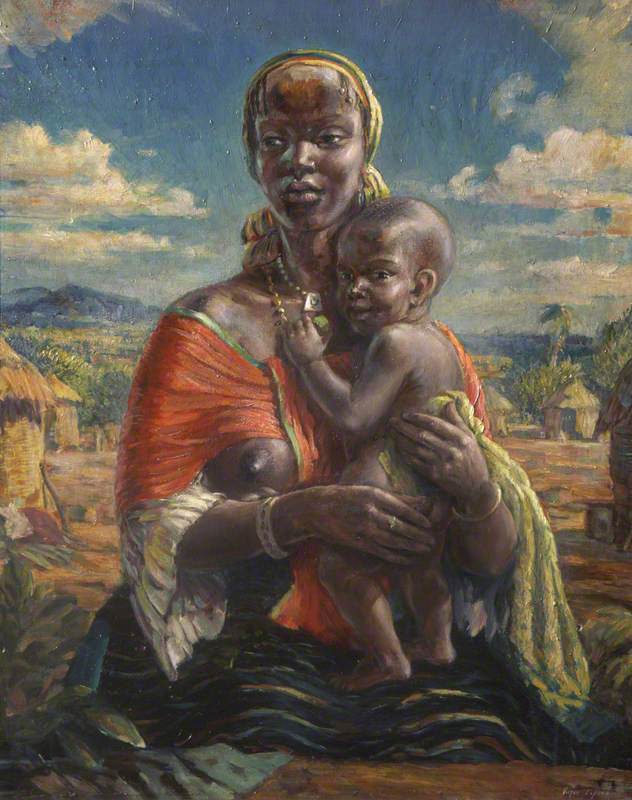

In contrast to Neuschul's Black Mother, renowned portrait artist Thomas Cantrell Dugdale's earlier Motherhood painting shows a peaceful nursing baby with the mother figure calmly gazing on the child nestled in her arms, unconcerned about anything apart from being a mother. The themes of connection and gazing at one's child also appear in African Mother by Helen D. Kiddall, produced around three decades later than Dugdale's portrait.

Kiddall shows the softness and tenderness in the connection between the African mother and the child cradled in her left arm, as her right hand also appears to lovingly caress her baby.

Yet despite these few examples, Black motherhood has been visualised, in the main, as impossible, base or problematic.

Black motherhood was seen as inhuman, disconnected, and always political: especially during the years of European enslavement when Black women, and the children they bore, were treated as property and products in the machinery of the 'triangular trade routes'.

An enslaved woman nursing a white baby

1861–1865, envelope design by unknown artist

The Black women held captive within the system had little or no chance to wean and nurture their own children, yet these same women were used as wet nurses to the children of the plantation owners.

African Woman Breastfeeding Her Child

unknown artist

In African Woman Breastfeeding Her Child, the downcast woman is barely connected to the oversized child at her breast. Further interrogation of the artwork, held at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in London, shows one hand loosely holds the back of the man child – whose arms are bigger than his mother's – while her other hand tightly grips her skirt. The woman is fertile and nourishing the child, but without evident emotional investment.

Nourishing and nurturing are central themes of motherhood. The life stories of Mary Seacole and Betty Campbell illustrate these concepts.

Mary Jane Seacole, née Grant

1869

Albert Charles Challen (1847–1881)

Mary Seacole was a Jamaican-Scottish nurse in the Crimean war. During her time there she noted, with some satisfaction, in her 1857 memoir, that soldiers in the Crimea referred to her as a mother figure: 'Their calling me "Mother" was not, I think, altogether unmeaning'. When Seacole met a new injured soldier she would ask, 'Who is my new son?', then add, 'all these fine fellows you see here are my Jamaican sons, are you not?' and the reply came, 'We are, Mrs Seacole, and a very good mother you have been to us.'

Seacole was not the only nurse in the Crimea, or elsewhere, to be referred to as a maternal figure: someone who is older, confident and caring. The mother figure is often readily accepted by people who desire a significant female role model in their lives, especially if the original mother figure is unable to fulfil that role. They may accept the nearest suitable alternative, like Mary Seacole or Betty Campbell who both stepped into the role as surrogate mothers to provide skilful care and services to those who needed them.

Betty Campbell (1934–2017), MBE

2021

Eve Shepherd, Castle Fine Arts

Rachel Elizabeth Campbell, MBE, known as Betty Campbell, is the subject of the first statue of a named, non-fictionalised woman in Wales. Eve Shepherd's 2021 bronze and black granite sculpture shows Campbell as Wales' first Black headteacher. The sculpture was selected by votes during a BBC Wales campaign for 'Hidden Heroines' by Monumental Welsh Women.

Betty Campbell, who became a teacher in 1963, was born in Cardiff in 1934 to a Welsh-Barbadian mother and a Black Jamaican father. This piece of public art located in Central Square, Cardiff reflects Campbell's achievements in the classroom and community, especially her public, maternal role as teacher and headteacher. The figures around the base of the sculpture of Campbell's bust show children of various ages and ethnicities including a girl wearing a hijab, a boy wearing a patka, and groups of other children throughout all eras being nurtured with piles of books and educational toys.

In place of a parent (in loco parentis), Betty Campbell, and other teachers, take on mothering roles and are seen as carers in an environment where they supervise other people's children for many hours each day. They can become objects of affection, or substitute parents where there is a need. Betty Campbell was a mother figure to her own children and the hundreds of children who knew her as a teacher.

Another Welsh demonstration of the motherhood connection is shown in John Pratt's 1955 black and white photograph of Dame Shirley Bassey and her mother Eliza-Jane Metcalfe working together as they wash up crockery using an enamel bowl.

Dame Shirley Bassey is one of six siblings born to her white mother. Bassey's mother, Eliza-Jane Metcalfe, may have been an unusual example of motherhood in Britain in the twentieth century when a white mother to a Black child was viewed negatively. Bassey's father was the Nigerian Henry Bassey and, after Shirley Bassey's birth, the family lived in Tiger Bay, Cardiff.

Metcalfe was raised in South Bank, Middlesborough but had to leave the area and move to Cardiff to raise her children. Although not totally accepting of dual heritage children, Cardiff had a better reaction to families of mixed heritage than much of the UK in the early part of the twentieth century. Wales is recorded to have had Black people in local populations since 1786. Metcalfe, as a mother of Black children, was viewed to have tainted the trope of virginal, white motherhood.

Early seventeenth-century depictions of revered motherhood in art were all white, reproducing the misrepresentation of Mary, the mother of Jesus, as the standard of maternal perfection. In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, there have been adjustments to the range of images that are used to depict motherhood. These now help to acknowledge that the peoples of the earth all originated from the African continent and Black motherhood is at the centre of humanity.

Marjorie H. Morgan, playwright, director, producer and journalist