The title of Michael Armitage's current exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, 'Paradise Edict', comes from a work made by the artist in 2019.

This painting seems to depict a tropical idyll, made up of lush foliage and blue skies. Yet a closer look reveals a more violent scene overlaid on top of the verdant green background: disembodied feet are suspended in the sky and hands pull forcefully at ankles. The serpentine coils rising up one of the ghostly figures echo the writhing tree branches nearby and suggest this is very much a fallen Eden.

The Paradise Edict

2019, oil on lubugo bark cloth by Michael Armitage (b.1984)

Paradise Edict is one of 15 oil paintings by Armitage on show at the RA in an exhibition that challenges cultural assumptions of Africa. The exhibition travels from the Haus der Kunst in Munich and, like that display, this one presents his paintings alongside works by other East African artists.

The recent Munich exhibition was the 36-year-old's first major museum presentation but, since his inaugural UK show at White Cube in 2015, his rise has been rapid, with solo exhibitions at the Museum of Contemporary Art Sydney, MoMA, New York, and South London Gallery.

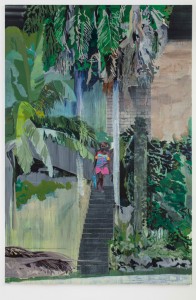

The Chicken Thief

2019, oil on lubugo bark cloth by Michael Armitage (b.1984)

Born and raised in Nairobi, Armitage studied painting at the Slade School of Fine Art followed by the Royal Academy Schools. Now he divides his time between London and Nairobi, although Armitage is clear that 'in terms of a sense of belonging, I only have that in Kenya'.

Kenyan society and landscape, as well as his own experiences of the country, form the backdrop to much of Armitage's work, yet the range of his source material is wide and diverse – from pop culture and politics to personal memories and art history.

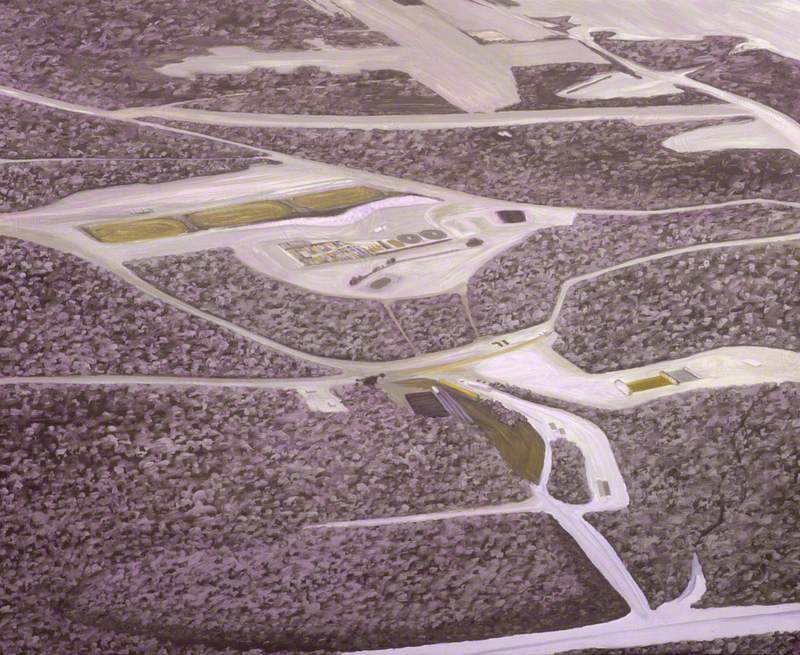

Nyayo

2017, oil on lubugo bark cloth by Michael Armitage (b.1984)

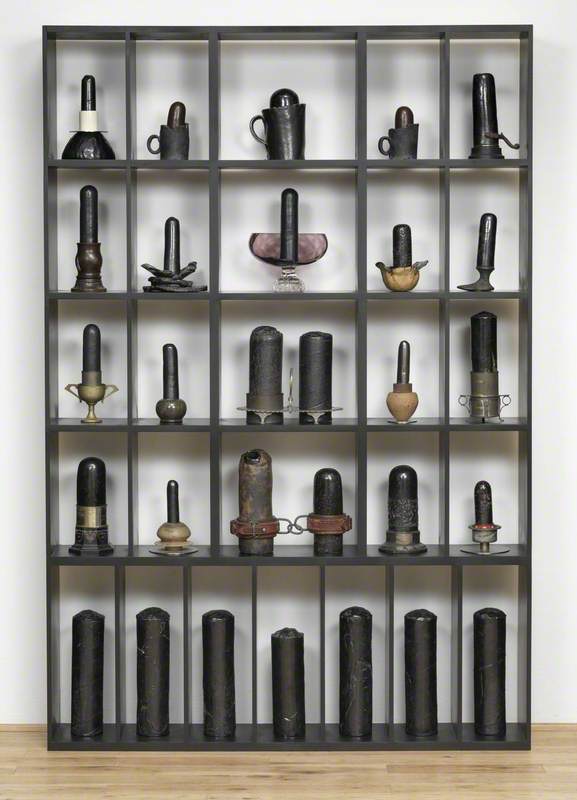

If Armitage's subject is rooted in East Africa, so too are his materials. The artist's large-scale works are painted on stitched-together strips of lubugo, a bark cloth used by the Baganda people of Uganda as a burial shroud. The cloth's resistance to paint led Armitage to build up thin washes of oil, which he then vigorously rubs, while the uneven texture of the material – featuring holes and stitching – becomes part of the work itself. His use of this unique painting support also signals a break with the European tradition of painting on canvas. In fact, Armitage's contemporary images of Kenyan life also frequently – and overtly – engage in a dialogue with Western art.

Nyayo (2018), for example, which depicts a naked figure ensnared by a snake, is modelled on the ancient Laocoön, while simultaneously referencing the Moi regime's practice of torturing political prisoners with snakes.

The Flaying of Marsyas

2017, oil on lubugo bark cloth by Michael Armitage (b.1984)

The Flaying of Marsyas (2017), the centrepiece of his exhibition at the South London Gallery in 2017, borrows its composition from Titian's work of the same name, but Armitage renders the tied-up figure in much more brutal terms, his open back laid bare like a slab of meat.

The Flaying of Marsyas

c.1570–1576, oil on canvas by Titian (c.1488–1576)

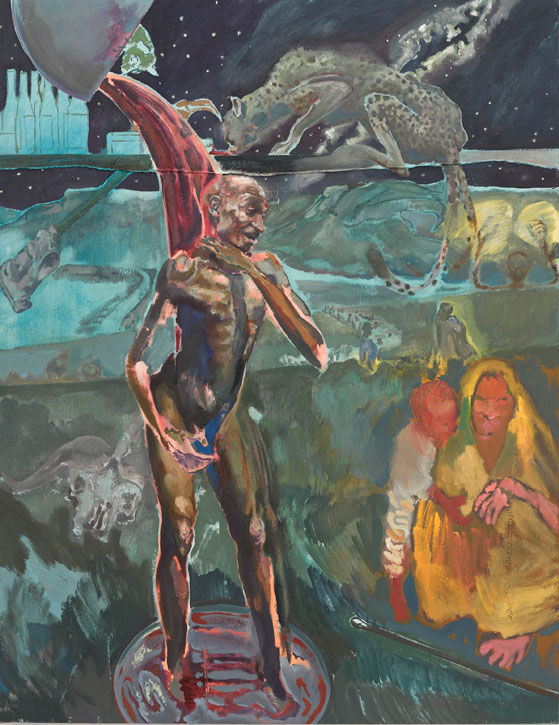

Titian's Pietà is the starting point for the figure Mydas (2019), in a painting that reworks the Midas myth. Armitage's version is set in a drought-addled landscape, the naked figure showered in blood while being watched over by a spectral cheetah.

Mydas

2019, oil on lubugo bark cloth by Michael Armitage (b.1984)

Armitage's seductive use of colour belies the violence and strangeness inherent in his paintings. His dream-like palette owes much to Paul Gauguin and yet, while his work can be seen as a rebuke to the French artist's colonial fantasies, he often plays with ideas around the exotic. His reworking of art history also allows him to challenge accepted ways of looking and to reframe 'otherness'.

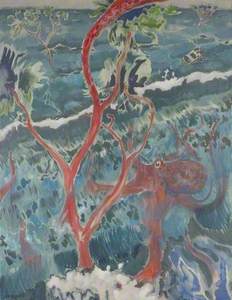

Baboon

2016, oil on lubugo bark cloth by Michael Armitage (b.1984)

While the reclining pose in Baboon (2016) recalls Édouard Manet's Olympia, the baboon's attempts to protect his modesty with an oversized bunch of bananas attracts rather than distracts our gaze. The overt sexuality of the image also speaks to the eroticism embedded in exoticising views of Africa.

Olympia

1863, oil on canvas by Édouard Manet (1832–1883)

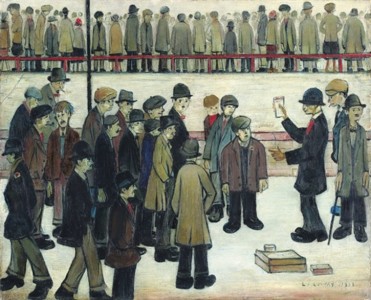

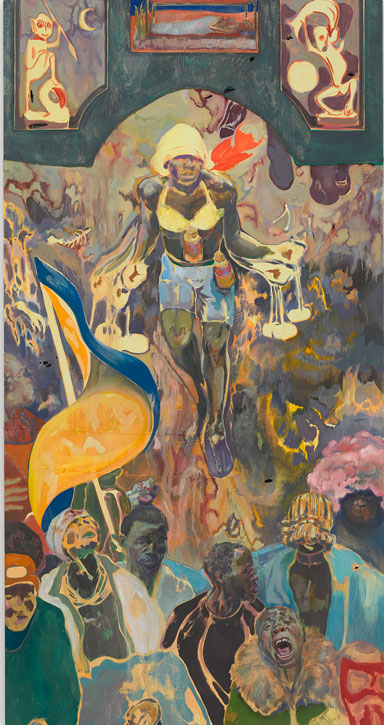

The highlight of the RA exhibition, which is organised into three thematic sections, is a series of eight paintings Armitage made about the 2017 Kenyan parliamentary elections. These works developed from Armitage's study of an opposition party rally in Nairobi's Uhuru Park, the frenzied atmosphere of which is captured in The Fourth Estate (2017).

The Fourth Estate

2017, oil on Lubugo bark cloth by Michael Armitage (b.1984)

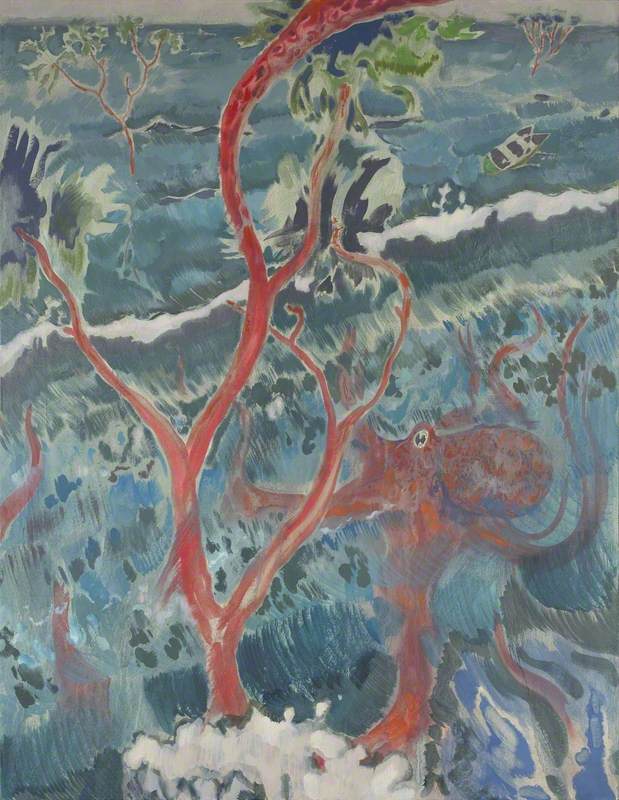

Based on Goya's etching Disparate Ridiculo (Ridiculous Folly, c.1820), Armitage's painting also shows several figures sitting on a tree, its tentacle-like branches reaching down towards a crowd of demonstrators below. This calls to mind the squirming branches in Paradise Edict, as well as a more fantastical work from 2016 titled The Octopus's Veil, in which the tentacles of a bright red octopus merge with the branches of a palm tree.

Pathos and the Twilight of the Idle (2019) takes Titian's Assumption of the Virgin as its inspiration but rather than an ascent into heaven, we're given a descent into hell – with smoke instead of clouds.

Pathos and the Twilight of the Idle

2019, oil on lubugo bark cloth by Michael Armitage (b.1984)

The peaceful protesters on the left-hand side of The Promised Land (2019) are relegated in the composition to the more violent figures on the right who are engulfed by billowing clouds of tear gas. This depiction of political unrest, which is drawn from real life, alongside more fantastical elements – a squatting baboon, the outline of a skeleton – is typical of Armitage's layered approach and his ability to weave many narrative threads at once.

The Promised Land

2019, oil on lubugo bark cloth by Michael Armitage (b.1984)

The RA exhibition also highlights the extent to which Armitage's work is indebted to East African modernism, with the section 'Mwili, Akili na Roho' featuring 35 works made by six artists working from the 1960s to the 1990s. This is curated in collaboration with the Nairobi Contemporary Art Institute, a non-profit exhibition space set up by Armitage in 2020 to support the development of art in East Africa (his commitment to the region is also clear in the charity edition, Dream and Refuge, which he released last year in association with White Cube in aid of Kenyan communities affected by the pandemic).

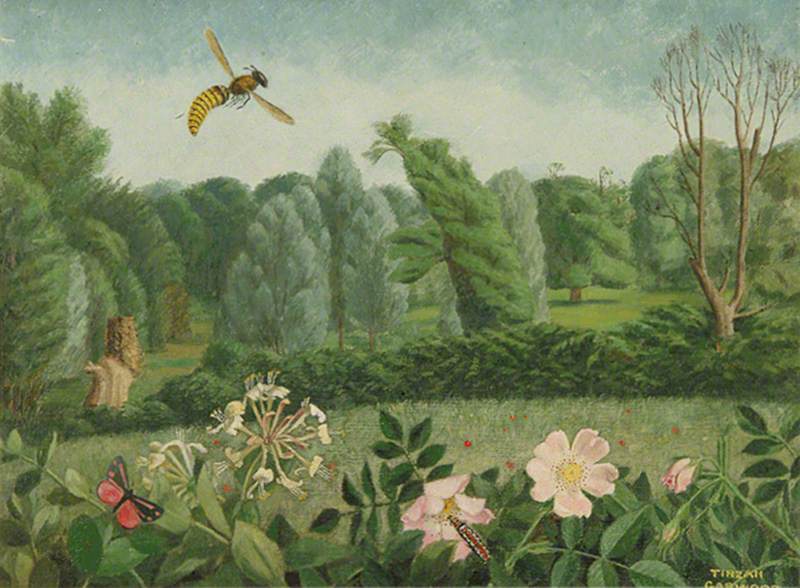

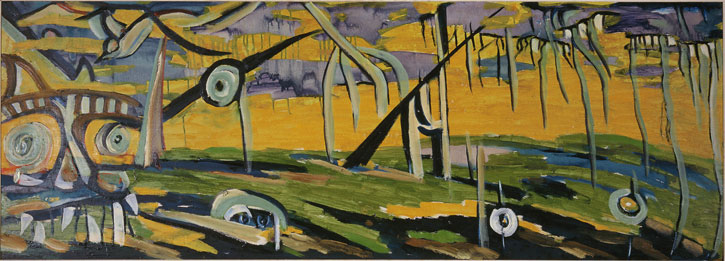

Armitage's tree motif seems lifted from Sane Wadu's My Life (1980–1990), whose composition is cut through by a backwards-bending tree, while Elimo Njau's Dream Landscape is reminiscent of the artist's own dream-like settings.

Dream Landscape

1968, oil on canvas by Elimo Njau

Elsewhere, the combination of lush landscape and horror in Asaph Ng'ethe Macua's The Genocide (which you can see in this video at 9 minutes 3 seconds), in which women hang upside down above a river, pre-empts Armitage's portrayal of Africa as a place of complex, conflicting forces.

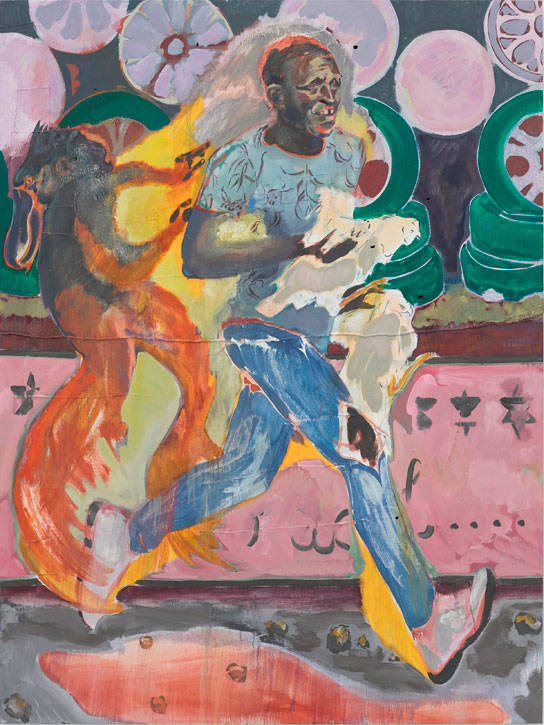

It's from Meek Gichugu, however, that Armitage gets his surrealism and his contorted, hybrid figures.

Untitled (Brother Wise Hooking Wisdom & Freedom)

c.1992, oil on canvas by Meek Gichugu

In combining these East African modernist sources with those from the European canon, Armitage unites two artistic traditions, giving them equal prominence in richly layered works.

Imelda Barnard, freelance writer and editor

'Michael Armitage: Paradise Edict' is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, from 22nd May to 19th September 2021