In their 2013 book Horror in Architecture, Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing asked, 'why spend time on horrifying things? Isn't life difficult enough?'

Citing the seventeenth-century Italian writer Antonio Rocco, they claimed that we should 'look at problematic subjects because they are instructive. And because their opposite, anodyne beauty, contains a dangerous surfeit of sweetness'.

For Comaroff and Ker-Shing, 'deviance teaches; charm will make you sick'. If this is the case, perhaps a similar tendency, a penchant for spending time on 'horrifying things', a propensity towards distortion and dissymmetry and a preoccupation with bandits, murderers, skeletons and sexual deviants, led the Scottish artist Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002) to proclaim herself the 'high priestess of the grotesque'.

Her paintings, produced between the late 1950s and early 2000s, abound with monstrous, macabre visions. Works such as The Bridegroom or Woman with White Hair stand as the very antithesis of the tasteful, drawing room gentility of her contemporaries Elizabeth Blackadder and Barbara Rae.

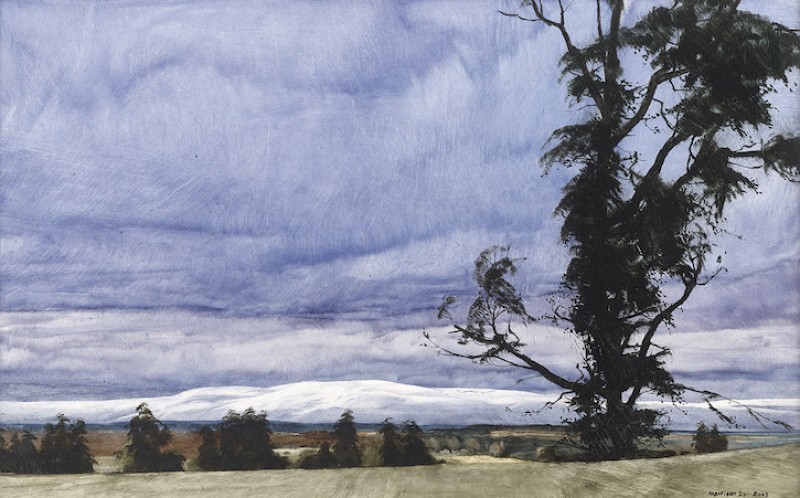

Sea Ice – Northwest Passage

2018

Barbara Rae

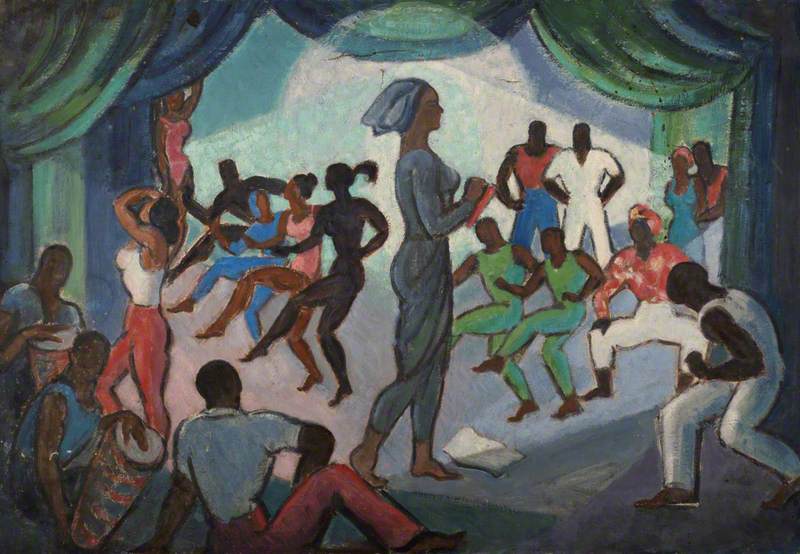

Douthwaite's early career focused on dance, movement and mime. She trained as a dancer with Margaret Morris in Glasgow and later joined Morris's Celtic Ballet, with whom she toured in the mid-1950s before abandoning her dance career to pursue her interest in art.

Katherine Dunham Dance Company Rehearsing, Empire Theatre, Glasgow

1952

Margaret Morris (1891–1980)

A self-taught artist with no formal training, her circle in the late 1950s included fellow ex-patriate Scottish painters living in England, including William Crozier, Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde. In the 1960s, she travelled with her husband, the artist and illustrator Paul Hogarth, and spent time with the poet Robert Graves, writer Brendan Behan and others.

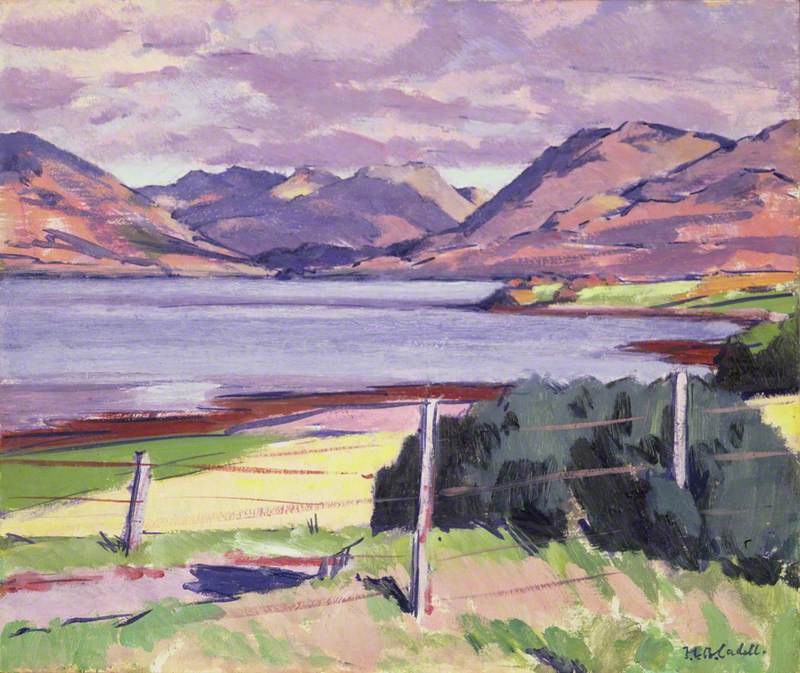

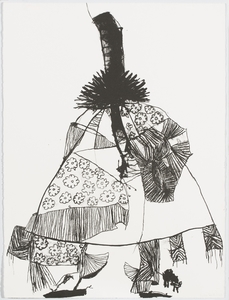

Masked Figure Venetian Carnival

1950

Robert Colquhoun

Douthwaite's disregard for the mores and conventions of bourgeois society and lack of an art education have led to her being critically framed as an outsider, a rebel working on the margins of the art world. However, in spite of her nomadic and unconventional life, she was, in fact, remarkably successful from the very start of her artistic career.

For an untrained artist from a modest background, it is striking that she was offered her first solo show in 1958 at the 57 Gallery in Edinburgh, only a couple of years after starting to paint professionally. In 1967 she was included in the iconic 'Fantasy and Figuration' exhibition at the ICA, and she went on to exhibit work in numerous solo and group shows in the UK and internationally, including a solo show at Glasgow's Third Eye Centre in 1988.

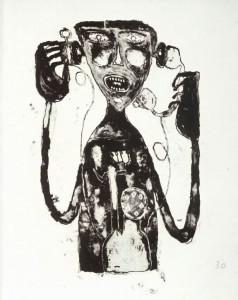

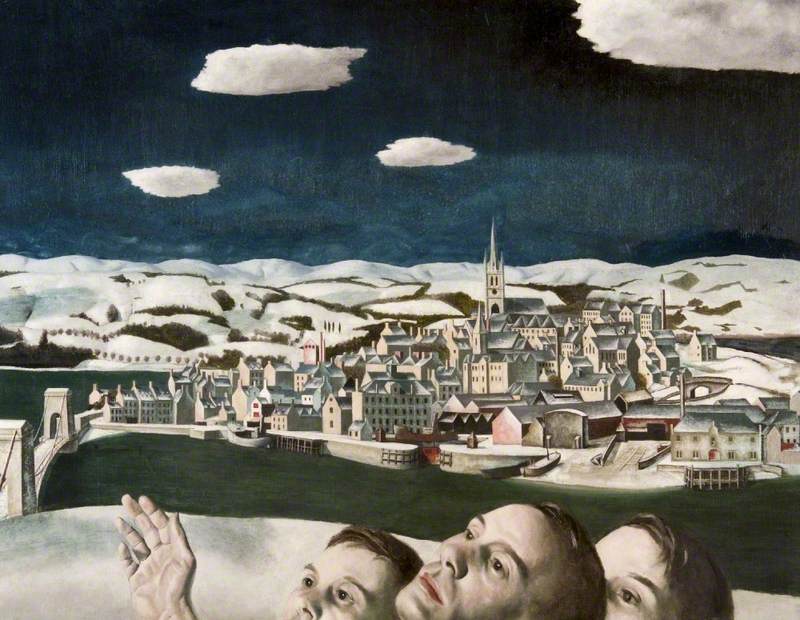

Final Instructions before Take-Off

1976

Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002)

The fact that Douthwaite did not attend art school resulted in works that the artist and critic Tom Lawson has referred to as having a distinctly 'unschooled quality'. Reflecting on some of the formal commonalities between their paintings, such as the dissonant use of colour, Lawson has claimed that he and Douthwaite shared 'a kind of aesthetic non-conformity because we haven't been trained'.

There is little tonal harmony in Douthwaite's paintings, a feature that adds to the jarring, discordant themes of her work. As a student in St Andrews in the 1970s, Lawson curated a large solo show of Douthwaite's paintings. The subjects included angry dancers, embalmed creatures, female spies and an abstracted portrait of the murderer Charles Manson, Buzzing Stinking Grass.

The painting was one of a series focusing on Manson, his 'girls', the so-called Manson Family and the killing of actress Sharon Tate. In it, Manson appears as a warped, contorted, grinning skeletal head against an acidic, bile-green background.

Such a 'calculated, distinct and determined use of colour, a contrast between tone and tonality to an emotional effect', was, for Lawson, one of the extraordinary aspects of Douthwaite's work.

Here, in a portrayal of what she deemed 'imaginary portraits of mis-directed power', the sadism and perversity of Manson's crimes are rendered visible through Douthwaite's nauseating palette and the twisted, reptilian cast of the murderer's skull.

The critic, artist and curator Cordelia Oliver wrote that 'every Douthwaite painting is like a performance', that the works always conveyed the sense of 'an actress trying to break free of the two dimensional straightjacket'.

Douthwaite's early career undoubtedly influenced her paintings: they reveal an enduring interest in performance and performativity both as subject matter (dancers and performers are frequent figures) and through an expanded painting practice that occasionally included elements of performance, such as her 1975 multi-media work Inanna, held at Edinburgh's Traverse Theatre, in which huge screened images of her paintings were accompanied by moving figures in costumes based on those in the paintings.

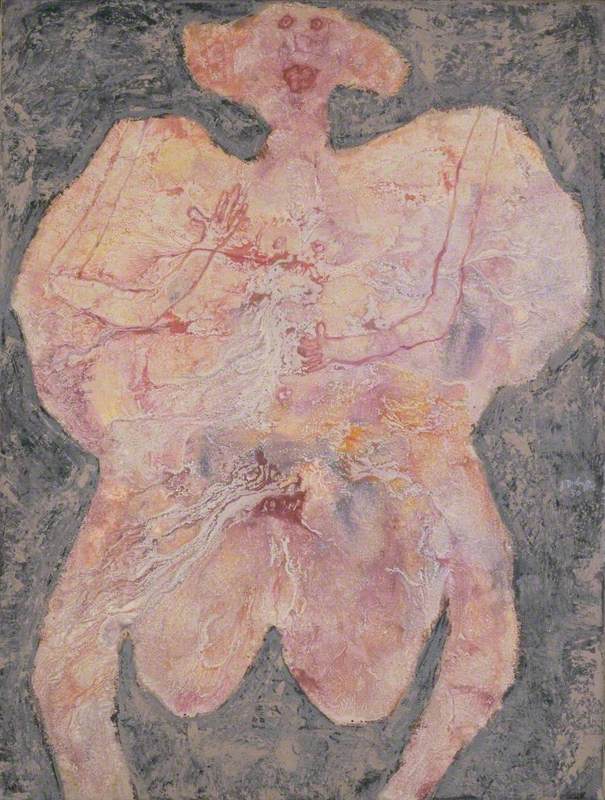

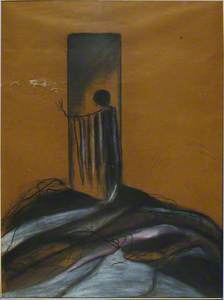

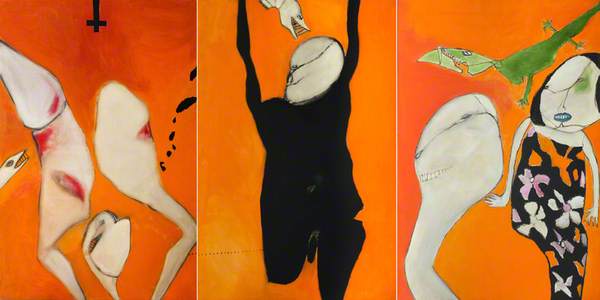

The Queen of Heaven (Inanna)

1970–1980

Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002)

As well as working as a dancer, Douthwaite had also worked as a mime artist and a set designer for other dancers and choreographers such as Lindsay Kemp, and the overlaps between her two creative passions, performance and painting, are profuse.

In 1972, at the Compass Gallery in Glasgow, she exhibited a show of what the artist and arts promoter Richard Demarco described as 'a group of sensually phallic symbols of dancers' heads'. Her numerous paintings depict dancers and performers of all kinds.

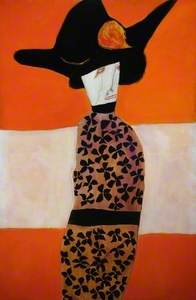

Black Spiky-Haired Geisha and Bent 'Topper'

1988

Pat Douthwaite

As well as the self-appointed 'high priestess of the grotesque', Douthwaite also proclaimed herself 'an illustrator of the subconscious'. There are clear affinities between her work and that of Expressionist and Surrealist artists in terms of both subject matter, style and approach.

In the year Hogey Bear was painted, for example, she had visited a Jean Dubuffet exhibition in Paris, and the similarities between Dubuffet's paintings of the 1950s and Douthwaite's early works of the 1960s are clear to see.

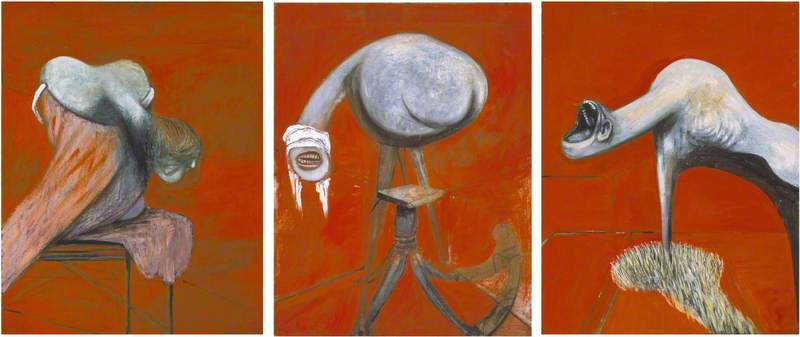

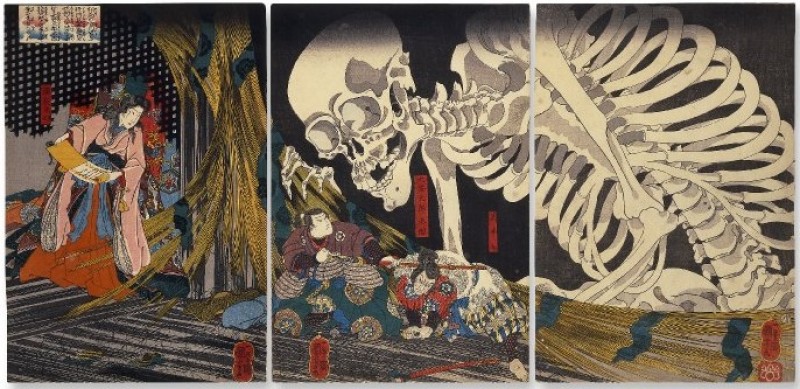

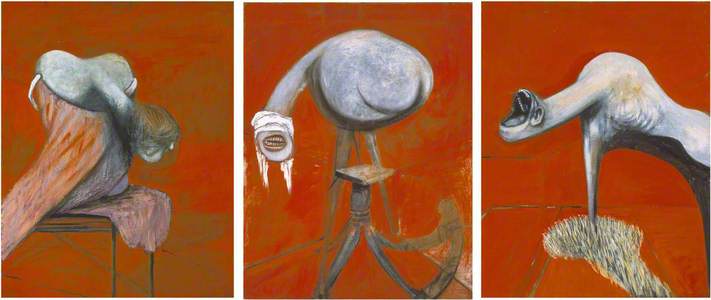

In her 1970 triptych The End of the World, another in the Charles Manson series, the formal resemblance to Francis Bacon's Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944) is striking.

Interestingly, Bacon's first art dealer, the Hanover Gallery in London, exhibited Douthwaite's Bacon-esque 'Sexy Skeletons' in the early 1970s, and many of the animalistic, phallic, open-mouthed skulls of her later paintings owe a debt to Bacon's studies, though Douthwaite's imagery was primarily concerned with particular cruelties suffered by women.

The recurrent themes and visual tropes of earlier Surrealist works are echoed in Douthwaite's work: women's bodies, contorted and laid bare; sex, death and altered states of consciousness; transgressive desire; twisted couplings and incongruous juxtapositions.

Her paintings of the 1970s and 1980s are littered with societal outsiders: drag queens, murderers and martyrs, such as 1979's portrait of the American outlaw Belle Starr, and the background of these figurative paintings are often nightmarish dreamscapes, fractured or distorted in some way.

Her later preoccupation with archetypal women (witches, goddesses and queens) recalls the work of Surrealist women such as Leonora Carrington (above) and Dorothea Tanning (below), as do her many paintings of women in ambiguous sexual encounters with animals, both devoured and devouring.

Her interest in concurrent, overlapping and integrated forms of creative practice represents another link with Surrealist approaches to art: in an early audition, she performed a Paul Éluard poem, and regularly incorporated poetry, performance, collage and design into her exhibitions.

Portrait of Myself with Malthy

Pat Douthwaite (1934–2002)

If the subjects of some of Douthwaite's works seem too unpleasant to dwell upon in their morbidity and horror, they are counterbalanced by what Douglas Hall, the first Keeper of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, referred to as the artist's 'keen satiric mind and acute sense of the ridiculous'.

View this post on Instagram

In 1969's Happiness is Green Shield Stamps, above, a female figure with a grinning, gargantuan head carries a glut of real, collaged shopping tokens. Hanging like a shawl over her hands, the woman's excitement is palpable.

Douthwaite's capacity to infuse her paintings with bathos is outstanding: there is a wry quality to many of her works, an absurd, darkly comedic element shimmering beneath seemingly repellent themes and subjects.

Her 'sexy skeletons' are both terrifying and incongruous, alternately human or bizarre, biomorphic abstractions. There are moments of genuine comic relief, which border on farce in some of her scenes.

Her characters, including self-portraits, often flaunt their alienation: Douthwaite's women, such as Woman in Orange with a Pink Bow (1997) wear huge, garish clothes or hats, their hair is untamed or enormous, their mouths, legs and arms akimbo.

Pat Douthwaite's paintings are some of the most singular and distinctive works by a twentieth-century Scottish artist. Why spend time on horrifying things?

In these highly original, wildly unconventional, formally and intellectually ambitious paintings, the high priestess of the grotesque produced some of the edgiest, most transgressive and idiosyncratic works in the history of Scottish art.

Susannah Thompson, writer and art historian

This content was supported by Creative Scotland