You can't really contest the most famous cultural exports of Liverpool: there are four of them, they sang 'All You Need is Love' and they add some £82 million to Liverpool's economy every year.

With no sign of Liverpool's Beatlemania waning, we thought it might be time to redress the balance – with a little help from some artists.

Liverpool is rich in artistic history. From Walter Crane to Alfred William Hunt, William Linton to Samuel Walters, Richard Ansdell to Christopher Wood, the city's art has broken free of the confines of the Mersey and travelled out across the UK – and the world. We've compiled four ways in which Liverpudlian art has made its presence known.

1. It was used in a campaign against President Truman

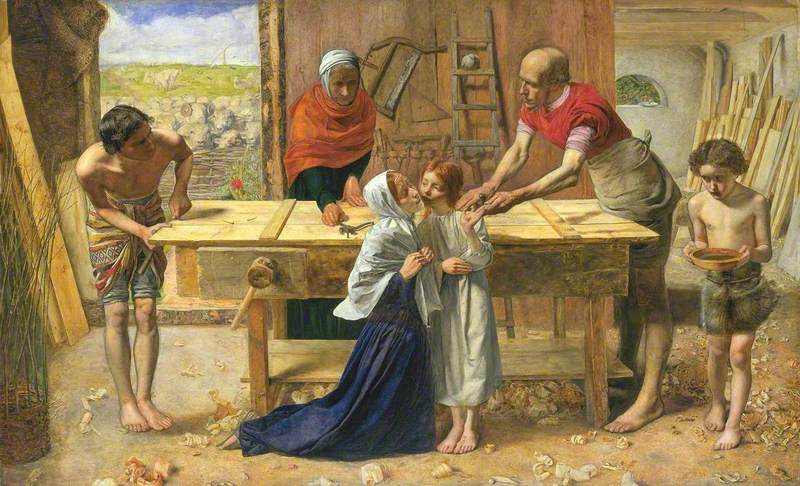

It was 1949, and a year since Aneurin Bevan had launched the NHS at Park Hospital, Manchester. 3,000 miles away, in Washington D. C., President Truman was trying to sell his similar vision of nationalised healthcare to the American people.

He had a harder time of it than his British counterparts: weary from war and scared of Communism, the American public wasn't convinced by what they saw as an overly intrusive federal government. The American Medical Association (AMA), opposed to the reform, was able to take this fear and run with it, attacking Truman's bill as 'socialised medicine'.

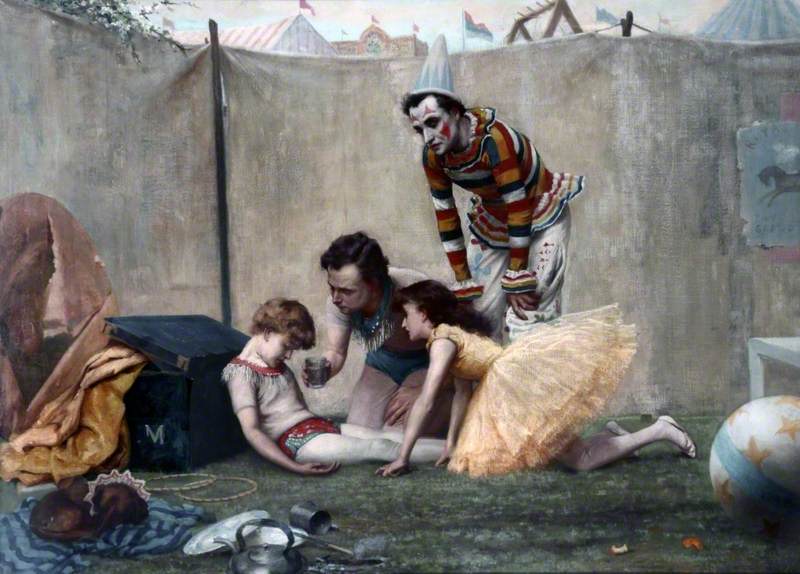

One of their most powerful campaign tools was The Doctor, a well-known (and well-loved) painting by Liverpool artist Luke Fildes, based on his personal, tragic experience – Fildes was inspired by the doctor who cared for his son Philip, before he passed away. The artwork was paired with the slogan 'Keep politics out of this picture', telling the public that matters of health were best left to kindly looking physicians, rather than the federal government. 65,000 of these posters were displayed, and helped to raise public scepticism for Truman's proposal.

Fildes died in 1927, so never saw his painting used by the AMA. He had produced many works inspired by the social realist movement, illustrated stories for Charles Dickens, and his work often depicted poverty in realistic and powerful ways: so perhaps he wouldn't have been too impressed by The Doctor being used in this fashion. Still, it's proof that America was looking to Liverpool long before the Beatles came along.

2. It played a key role in Britain's first modern art movement

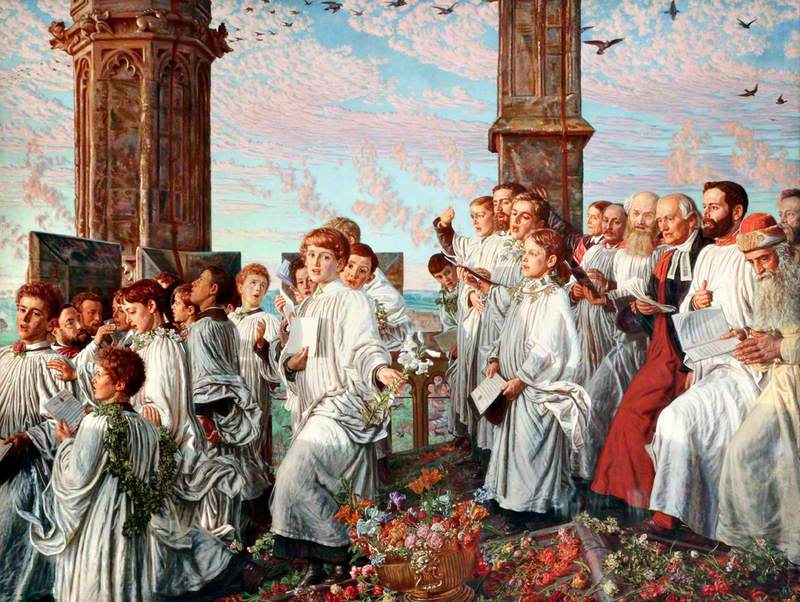

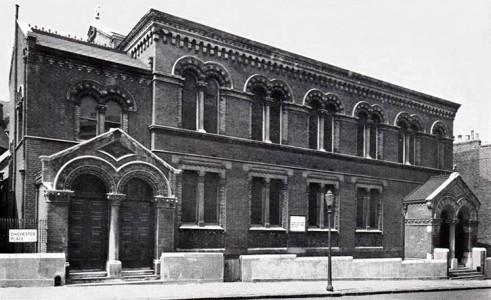

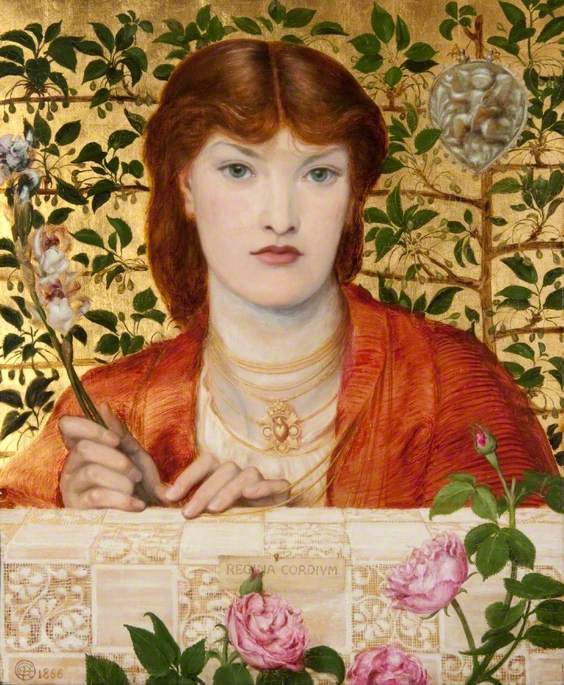

A city full of free spirit and intellectual curiosity; a desire to look at something cutting-edge instead of Old Masters; eager patrons, newly wealthy from booms in trading and banking, willing to take a chance on buying modern art: these were the ingredients that meant Liverpool was among the first places to welcome the then-controversial works of the Pre-Raphaelites in the 1800s.

The establishment of the Liverpool Academy – intended as a regional version of London's Royal Academy – also played its part. The Pre-Raphaelites saw their works displayed in Liverpool when the art world in London was still doubtful; the Liverpool Academy even offered to pay costs for paintings transported between London and Liverpool if they did not sell during their time in the north.

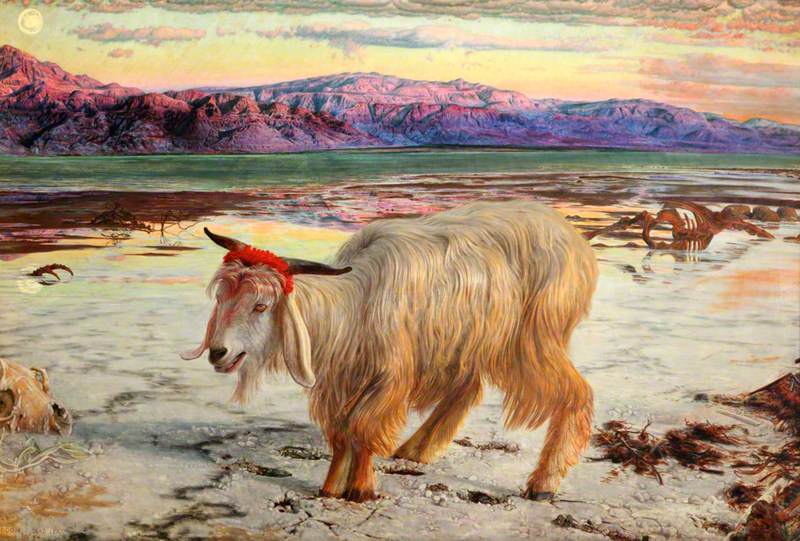

Strange, powerful works such as William Holman Hunt's The Scapegoat were displayed, and the Academy caused controversy among its members by regularly awarding its annual £50 prize to Pre-Raphaelite works. The controversy ultimately caused a split in the Academy's ranks and the formation of a breakaway society, the Liverpool Society of Fine Arts.

Christopher Newall, curator of the Walker Art Gallery's 2016 exhibition of the Pre-Raphaelites, spoke to the BBC about the phenomenon of wealthy patrons in Liverpool, such as George Rae, who had more Rossettis in his collection than were anywhere else in the world:

'There were lots of people who made lots of money in their generation and didn't have a preconception of what kinds of art they should have on their walls... they came to it with a delightful open-mindedness. They were often people of independent frame of mind, perhaps because of the traditions of non-conformism and Unitarianism that existed in the city... there was a sense that you didn't need to be in awe of the past.'

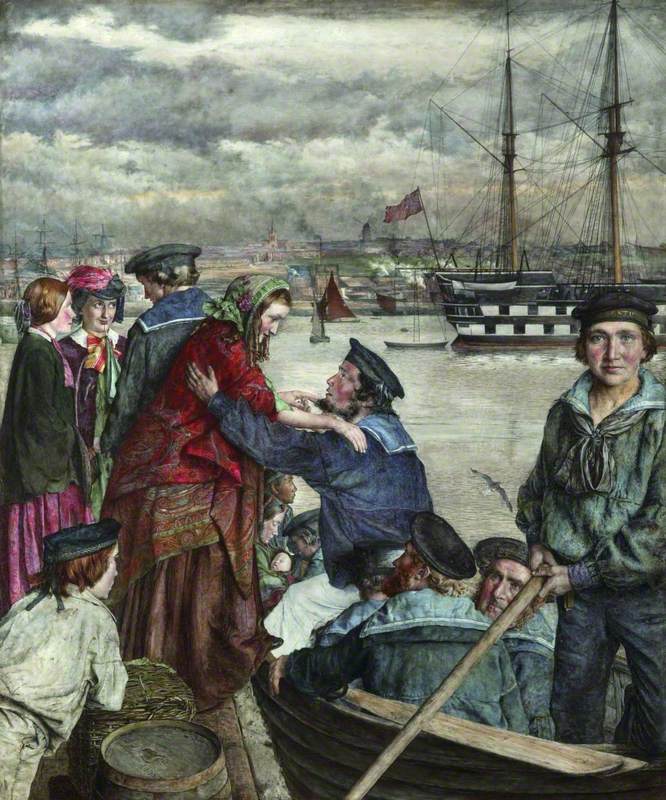

As a consequence, there was a generation of artists working in Liverpool influenced by the Pre-Raphaelite style, including William Lindsay Windus, William Davis, James Campbell, Daniel Alexander Williamson and John Ingle Lee.

3. It produced some of the most famous animal paintings of all time

George Stubbs – a Liverpool native – created Whistlejacket, one of the most famous animal paintings in existence; turn a corner at The National Gallery and you're confronted with the horse that feels like it's springing to life from the canvas.

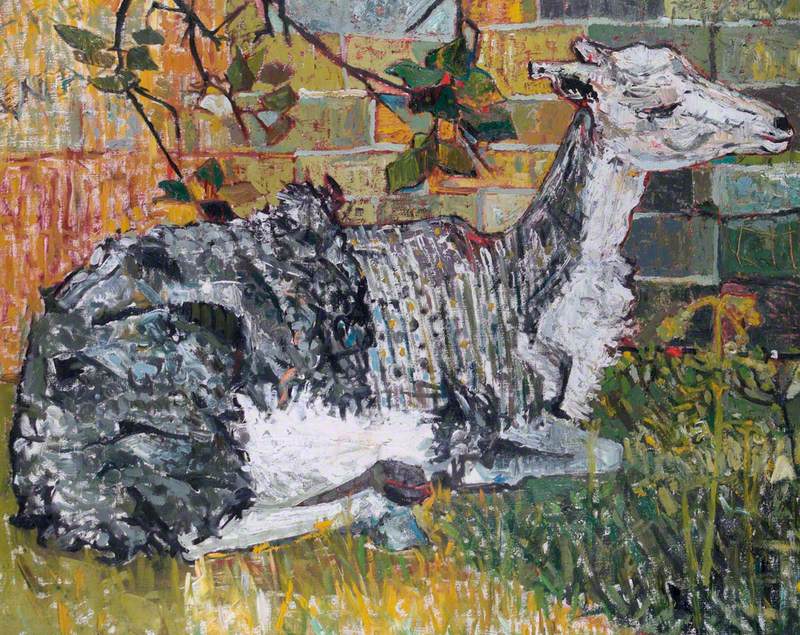

His interest in horses and lions is well-documented in Tate's collection. But it's also worth taking a look at Stubbs' other works.

Through his partnership with John and William Hunter, Stubbs was commissioned to paint animals far more exotic than horses: a rhinoceros, a moose, monkeys, a yak – all creatures that had been brought to Britain for study, from faraway lands.

Stubbs was as fascinated with animal physiology as he was with his art: he created 'The Anatomy of the Horse', considered a masterpiece of animal anatomy, and this interest in science led to a fruitful partnership with the Hunters.

One of William Hunter's theories was that the North American moose was a different species to the Irish elk. He commissioned Stubbs, who painted the moose and added a Romantic landscape for the creature, placing it back where it belonged in nature (rather that Richmond, where this particular animal had been rehomed).

This harmonious relationship between art and science was characteristic of Stubbs' work, and produced this strange yet stunning portrait.

4. It created a world-famous logo

'Nipper' the dog, gazing quizzically into the cone of a gramophone, adorns branches of HMV up and down the UK. He's also the official logo of Japanese-based firm JVC (and several other audio companies). But while Nipper the dog himself was a West Country citizen, from Bristol, the artist who captured his likeness on canvas – and made him famous – was from Liverpool.

Francis Barraud painted the terrier after his original owner – Barraud's brother – had passed away. Nipper really was intrigued by the sound coming from the gramophone, though in the original painting it was an 'Edison Bell cylinder phonograph'. Barraud, on presenting his original painting to the Edison Bell company, was told that 'dogs don't listen to phonographs'.

His bark his worse than his bite...

— The National Archives (@UkNatArchives) November 30, 2019

This painting by Francis Barraud was used as the basis for the HMV logo - who also based their name on the painting, 'His Master's Voice', eight years after purchasing the image in 1899.#ArchiveVoices @ExploreYourArchive

: COPY 1/147 pic.twitter.com/Mcts8WXV7k

Barraud subsequently took advice to modify the original painting and to render the horn in brighter brass. He went to the brand new Gramophone Company, Ltd. to borrow such a horn, and recalled: 'The manager, Mr Barry Owen asked me if the picture was for sale and if I could introduce a machine of their own make, a Gramophone, instead of the one pictured. I replied that the picture was for sale and that I could make the alteration if they would let me have an instrument to paint from.'

The Gramophone Company bought Barraud's modified painting, and the copyright to the image. It was taken to the United States and the rest is history.

Nipper listens to Front Row! “Dog looking at & listening to gramophone” by Barraud became HMV logo #DogsinPaintings pic.twitter.com/G98x9MBAeB

— BBC Front Row (@BBCFrontRow) August 16, 2016

The original 'His Master's Voice' painting still hangs in the offices of EMI, the successor to the Gramophone Company.

Several of Barraud's works are available to look at on Art UK, but his other work as an artist has largely been overshadowed by the fame of Nipper.

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer