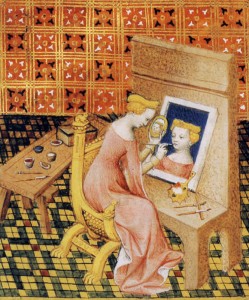

On 19th November, The Courtauld Gallery reopened to the public after undergoing a three-year £57 million renovation. The modernisation included the opening of new exhibition spaces on the third floor which will display the Karshan Gift, 24 post-war and modern drawings by artists such as Cézanne, Kandinsky and Giacometti. The curved wall above the spiral staircase now displays Unmoored from her reflection (2021) by the contemporary British painter Cecily Brown.

Unmoored from her reflection

2021, oil on linen by Cecily Brown (b.1969)

Featuring an eclectic selection, the exhibition does not have a specific theme but its title 'Modern Drawings' conveys its particular importance here as a collection of works by significant names from the twentieth century. The third floor of the gallery is practically dedicated to this time period, with another room newly devoted to the Bloomsbury Group, and the Katja and Nicolai Tangen Twentieth Century gallery displaying a rotating selection from the gallery's holdings from this time period.

The Courtauld Gallery

While the compelling drawings, donated by the artist Linda Karshan in memory of her late husband, collector Howard Karshan, may not have an explicit theme linking them, viewers are invited to consider the ways in which many of the works interrogate the lines between abstraction and figurative representation.

The Bloomsbury Room at The Courtauld Gallery

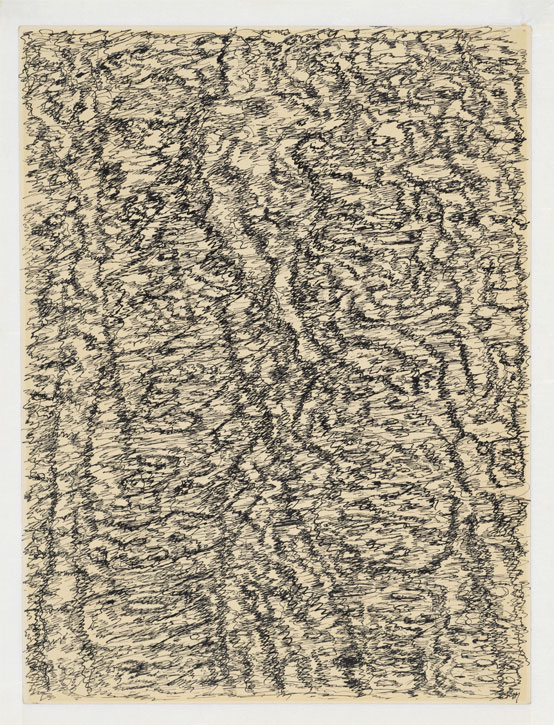

The Belgian-French poet, artist and writer Henri Michaux created a paper canvas of calligraphic inky marks that from afar create a mesmerising pattern that looks like a dissipating Rorschach test. In his ink drawings, Michaux sought an alternative, or a temporary escape, from the verbal, finding in this liminal space between writing and drawing, a 'release from words' and a 'new language'.

Between 1957 and 1959, Michaux published three books detailing his experiences with mescaline, but he also created a dizzying series of India ink drawings. Untitled (Mescaline Drawing) which was created after the artist indulged in the hallucinogenic drug, features in the exhibition. A lack of inhibition and a sense of freedom from the pressure of faithful representation of ineffable experiences embodied in the frantic pen mark which give off an aura of hypergraphia.

Tusch Mescalin

1957, ink on paper by Henri Michaux (1899–1984)

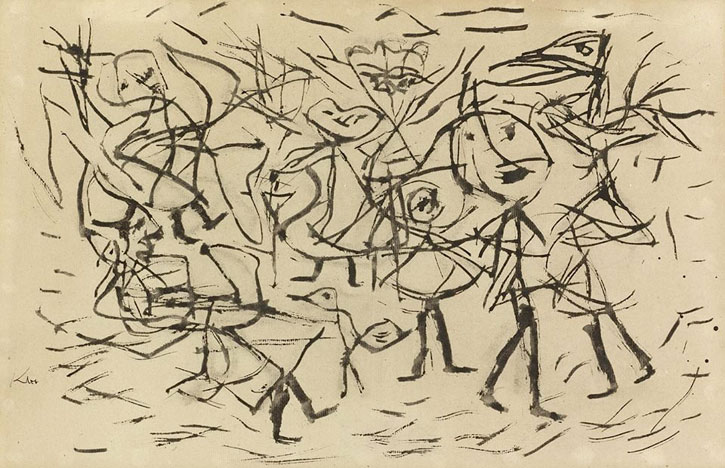

This question of abstraction and figuration also expresses itself in the works that attempt to depict the human body. What is the minimum amount of lines, for example, with which we would be able to recognise or interpret a scribble as a human figure? The deceptively crude mark-making depicted in Swiss-German painter Paul Klee's Children and Crows (1932) evokes the raw, unpolished and uninhibited nature of childhood drawings with their stick limbs and odd proportions.

Children and crows

1932, brush & ink on paper by Paul Klee (1879–1940)

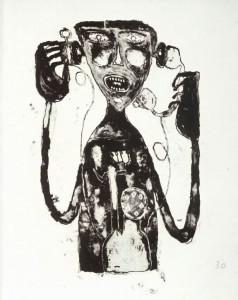

We look to distinguish between the children and the oversized crows in the commotion of Klee's short, quick, overlapping pen and brush marks. French painter and sculptor Jean Dubuffet's The Chatterer (1951), a work which also exudes a mischievousness and childlike humour in this image of a bulbous figure created out of builders putty, makes the eye look for the human form, for the raised right arm and the thin legs that stick out at impossible angles.

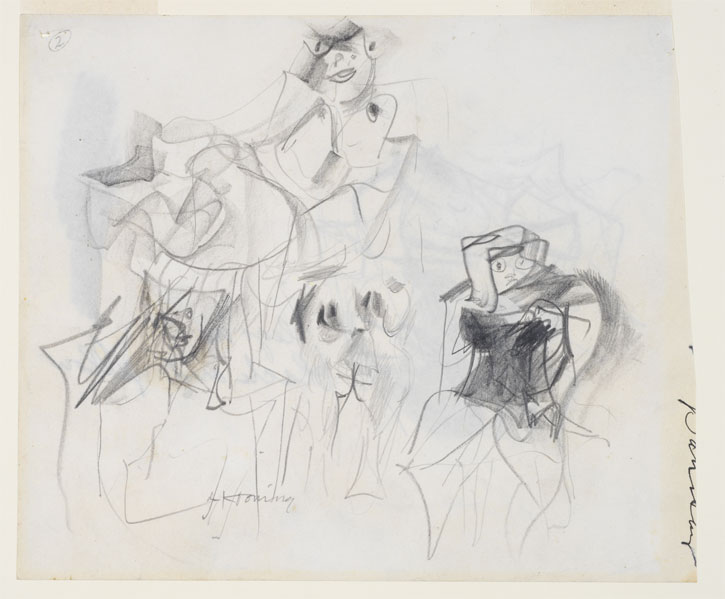

Studies of Women

1954, graphite on paper by Willem de Kooning (1904–1997)

In the featured works of German painter and sculptor Georg Baselitz and abstract expressionist Willem de Kooning, female figures are depicted as a kind of monstrous feminine. De Kooning's Studies of Women (1954), created after his infamous Women series of paintings completed between 1950 and 1953, and which he claimed was an outlet for his occasional 'irritation' with women, depicts two female figures – one naked, the other in a tight corset. The 'women' are blocky and angular in some places, rounded in others. The spaces where the artist erased lines are also visible; the image as a whole seems to align an oscillation between the abstract and the figurative, hinting at an uncertainty surrounding female sexuality.

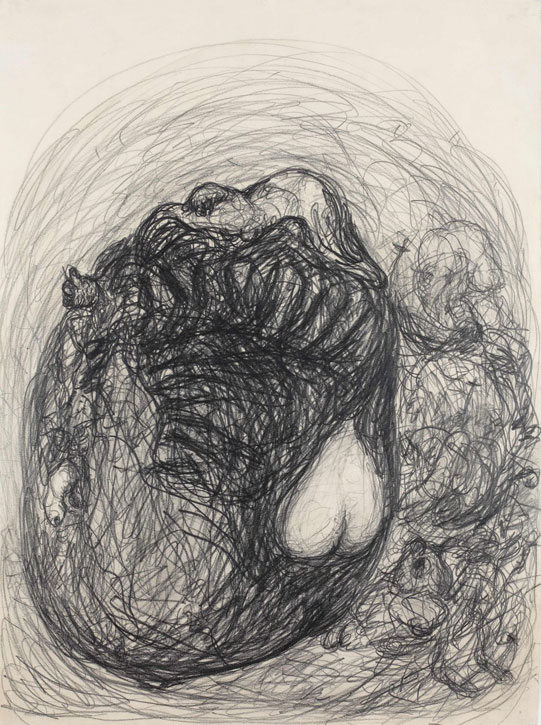

Untitled (Whip Woman)

1964, graphite on paper by Georg Baselitz (b.1938)

Baselitz's images are more extreme with his Untitled drawing from the 1964 Whip Women series conveying a grotesque interpretation of the female nude. The figure is depicted with a huge spherical body, a tiny head and similarly small legs. Her genitalia and stomach are enlarged, the latter is covered in hair. In a small hand she holds a whip she would not possibly be able to use. It would be comical if the overall atmosphere was not one of unsettling monstrousness.

Playfulness and humour rub up against darkness and unease. In fact, a sense of ambiguity and discomfort seems to emanate from many of the works in the exhibition. This is particularly interesting in the context of the re-opening of The Courtauld, the buzz about which felt reminiscent of the period after lockdown when reopening art institutions offered themselves as reprieves from the never-ending turmoil of dealing with COVID-19. These works at the top of the gallery seem to remind one that art is never consistently a place of comfort.

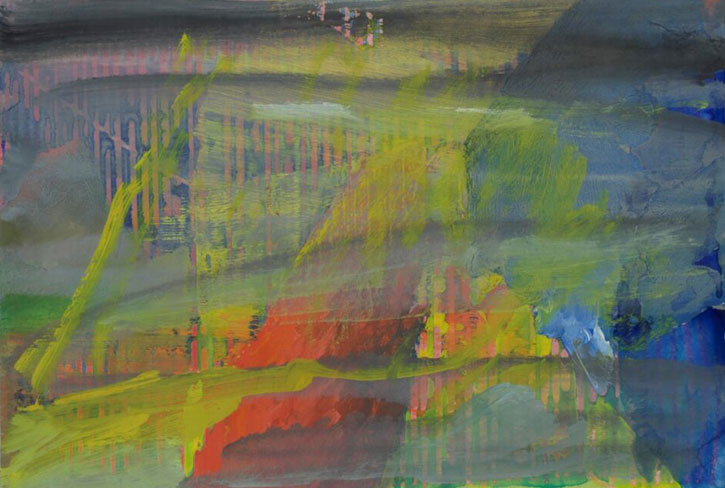

Untitled

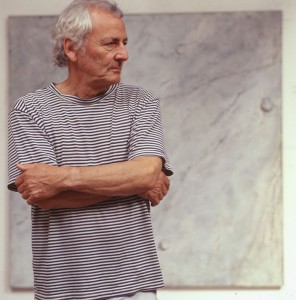

1985, oil on canvas by Gerhard Richter (b.1932)

There is agitation, confusion and violence expressed in these works created in the aftermath of the Second World War. It is in the visible grooves where the artist dug their pencil into the paper, in the thinner, sharper lines of graphite, in the acrid, radioactive colours of Gerhard Richter's watercolour, and in the cartoonish anthropomorphised Ku Klux Klan hoods of Philip Guston. It all provides a fascinating edginess – not to sound corny or too simplistic – that might not normally be associated with The Courtauld.

The Karshan Gift drawings are not just an outstanding acquisition for The Courtauld for the injection of experimental twentieth-century work they add to the gallery's collection: they are also a very worthy opening exhibition.

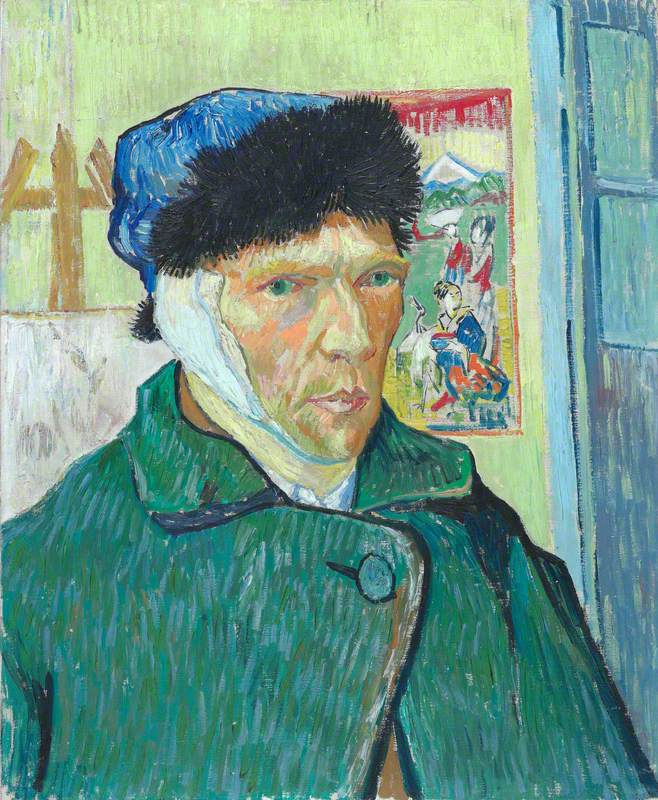

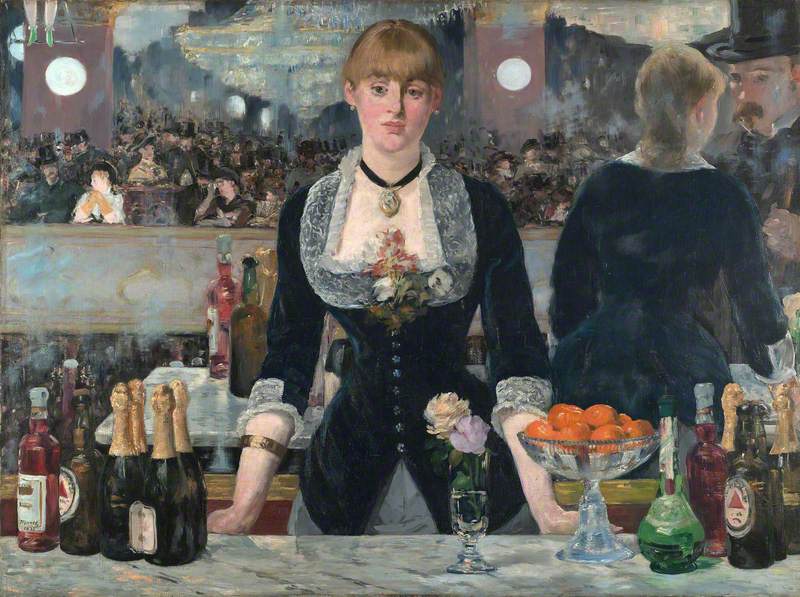

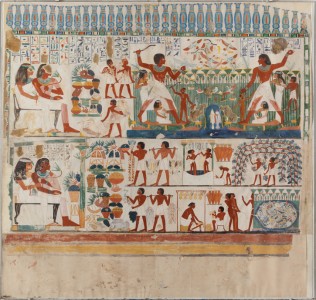

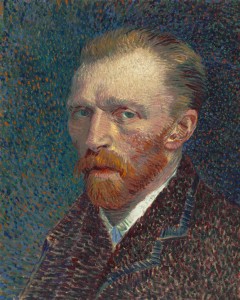

The drawings hold their own even amongst the big hitters currently on show in the newly refurbished LVMH Great Room such as Vincent van Gogh's Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear (1889), Édouard Manet's A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882) and Oskar Kokoschka's epic Prometheus Triptych, which dominates the Katja and Nicolai Tangen Twentieth Century Gallery and is on show for the first time in 15 years.

The Karshan Gift drawings still command attention, more of a quiet but still stimulating intrigue. In the less grand, more minimalist space of the Denise Coates exhibition galleries, they invite a closer examination, a slightly more intimate interaction with the works of artists around whom blockbuster exhibitions could have easily been organised.

In that respect, the viewer feels rather privileged to see these pieces in this way.

Aida Amoako, freelance writer