The moment in June 2020 when John Cassidy's statue of Edward Colston was torn down and trundled through the streets of Bristol to meet its watery end in the River Avon has been endlessly on my mind. It was a profound moment of collective action aimed at reimagining who and what is celebrated in our public spaces by questioning the objects already within it. For so long in Britain, we have struggled to acknowledge the impact of our colonial history, despite its visible legacies across the country.

At this juncture, when the Black Lives Matter campaign has brought this into sharp focus, it is a timely opportunity to re-examine aspects of British history which often go unrecognised. Art is a rich place to start, as many artists have been working through these histories long before the conversation became mainstream. Many inspirational artworks have emerged as a result.

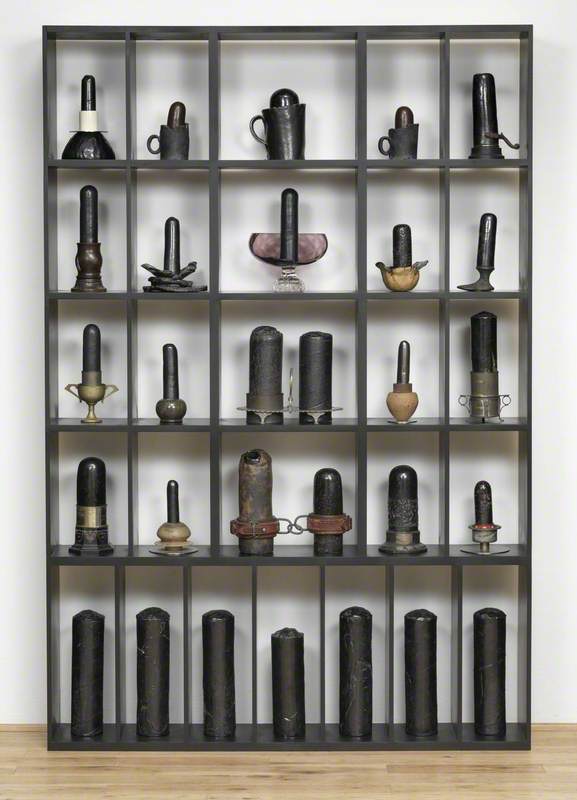

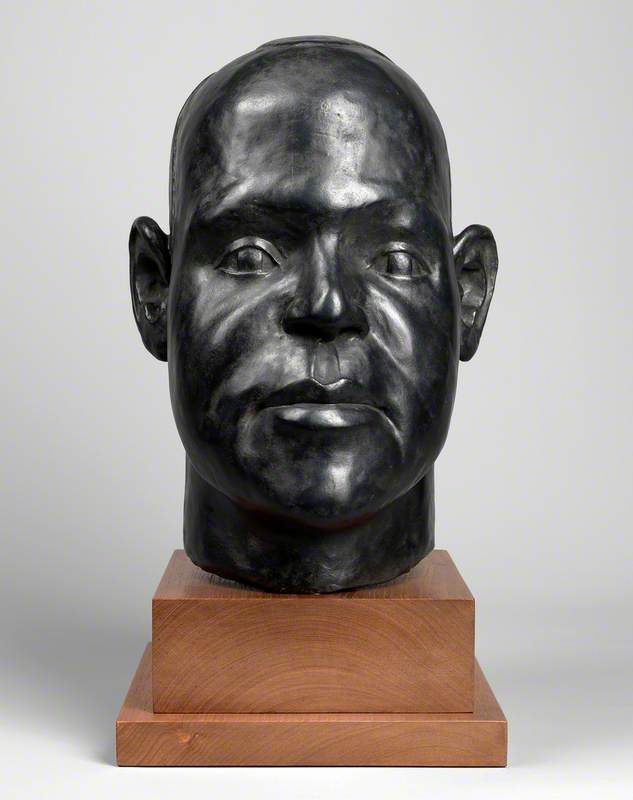

Donald Locke (1930–2010)

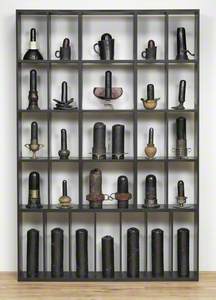

Donald Locke's Trophies of Empire of 1972–1974 consists of a display cabinet containing black ceramic forms which have been read variously as phallic symbols, bullets or stand-ins for colonial subjects.

Some sit directly on the shelves of the cabinet, while others are mounted on candleholders, trophies and silver service dishes – objects which might typically occupy a display cabinet of this kind. The most shocking aspect is that two of these objects are linked by shackles. While this is a clear allusion to slavery, Locke ruminates on the more subtle psychological aftermaths of European exploitation across the African diaspora through the use of the trophy.

Locke has explained that under British control, Guyana (formerly British Guiana) held a range of sporting events in which men could compete and win trophies. Although highly prized at the time, many such objects were discarded once the owners moved to Britain. The value of prizes given by colonial regimes is questioned and the audience is asked to consider who were the true winners in these circumstances.

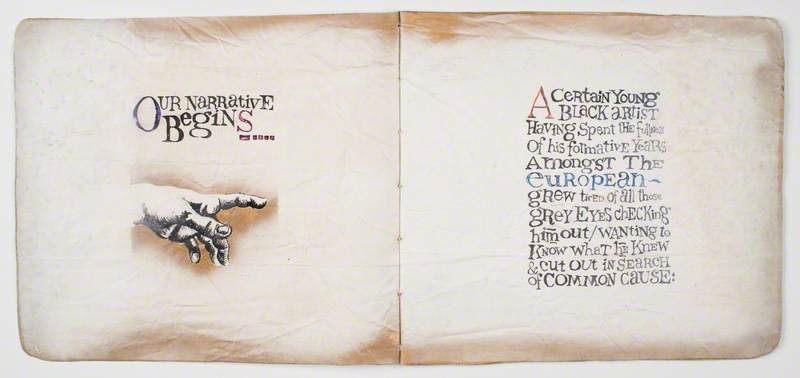

Keith Piper (b.1960)

Around a decade after Locke's original piece, Keith Piper (b.1960), a key member of the BLK Art Group, took inspiration from the work and its title, as well as from the Black Audio Collective's Expeditions One: Signs of Empire to create The Trophies of Empire.

In this installation, sculpture, painted canvas and audio are combined alongside a projection of a looping slide sequence of appropriated images and Letraset transfers to deliver a narrative interweaving Britain's imperial history with the socio-political context of the 1980s.

References to the racial tensions in Britain under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the profiling of black British people by the police serve to echo the actions of colonial forces in the nineteenth century.

Donald G. Rodney (1961–1998)

Another key figure in the BLK Art Group, Donald Rodney created Land of Milk and Honey II for the 1997 exhibition 'Nine Night in Eldorado' at the South London Gallery, which would turn out to be his last.

Land of Milk and Honey II

1997

Donald G. Rodney

The work is 'a eulogy to the memory of his father' whose death Rodney was unable to commemorate through the traditional Jamaican 'nine night' tradition. The work comprises a vitrine filled with milk and copper coins. As these materials are in the process of reacting with each other, the appearance of the sculpture changes over time.

The artwork's title alludes to the 'land of milk and honey' – the Biblical description of the promised home for the Israelites. For Caribbean immigrants travelling during the mid-twentieth century – Rodney's father included – this was how Britain was imagined, as a place of abundance and opportunity. The decay of the milk and coins speaks to the souring of those dreams and the reality of life in Britain for the Windrush generation and their descendants.

This piece combines Rodney's personal experience with a wider critique of Britain: by substituting money for honey Rodney makes clear that the British economy has benefitted from and driven the migration of people including his father.

Hew Locke (b.1959)

Hew Locke creates work which explores power and its preservation through images. His 2019 series Souvenir takes as a starting point souvenir busts of British royalty, including Queen Victoria.

View this post on Instagram

Locke creates a biting critique of empire by loading the busts with gaudy accessories, which he describes as weighing them down with 'the literal burden of history'. Among the accessories are medals from the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 and the Benin Expedition of 1897 – during which Benin City was destroyed and the Benin Bronzes were looted – and to make clear the links between violence, war and the British Empire under Queen Victoria. Through this, Locke problematises the sympathetic portrayals of royalty we see in paintings and period dramas.

Kara Walker (b.1969)

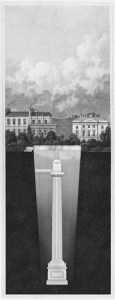

African-American artist Kara Walker sparked debate with her Hyundai commission Fons Americanus which took over Tate Modern's Turbine Hall in 2019.

From the top down the huge fountain tells stories of the Black Atlantic – the fusion of black cultures with other cultures from around the Atlantic – while alluding to the Victoria Memorial which stands outside Buckingham Palace. Like Hew Locke, Walker is critical of the British Empire.

In a subversion of the statue of Victoria, Empress of India, which is topped with a figure of Winged Victory, Walker uses her monument to foreground the harsh experiences of black people from Africa and its diaspora, questioning how we choose to memorialise our histories. The brutality of this history has ignited the debate over whether it is useful or appropriate for histories of violence against black people to be the subject of artworks.

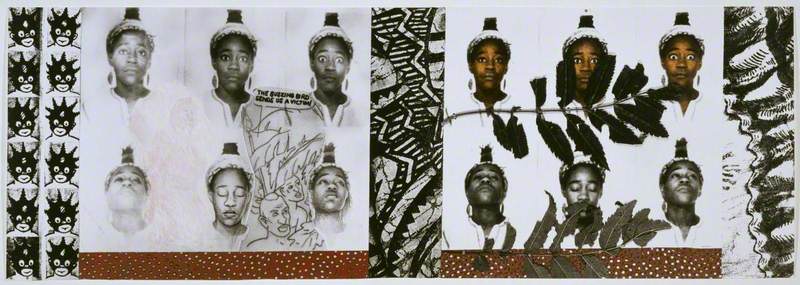

Sonia Boyce (b.1962)

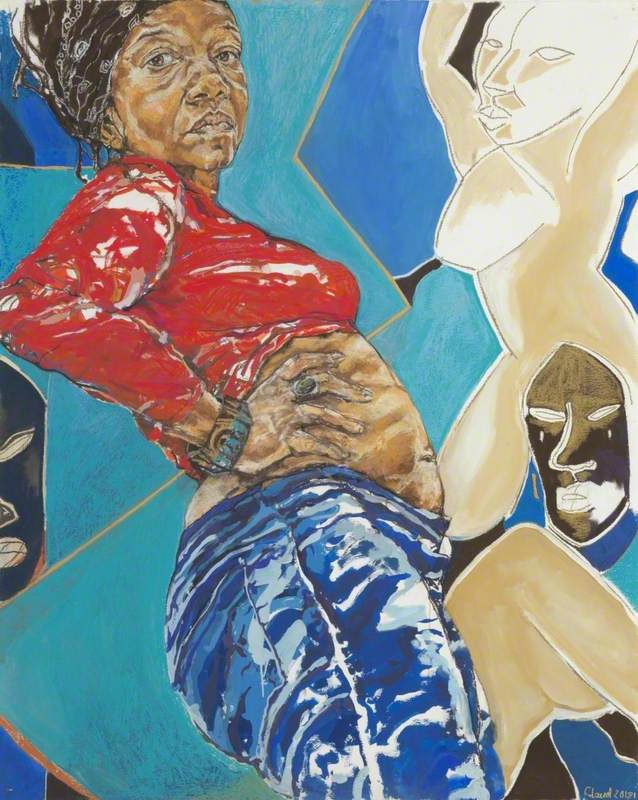

Known for her conceptual, collaborative and performative works, Sonia Boyce is forever adapting her artistic practice.

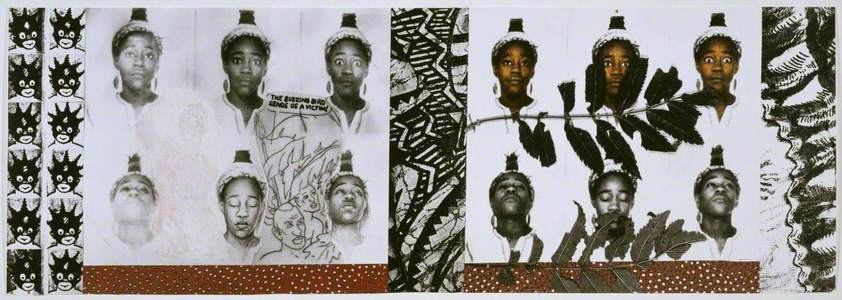

In this early work from 1987, Boyce takes herself as a subject, exploring her self-image in opposition to that proffered by popular culture, which is represented by the (racist tropes) of the 'pickaninnies' on the left of the image and the cartoon strip of two men in a jungle.

By contrasting these stereotypical images with a sequence of self-portraits – a mixture of photographs and drawings – Boyce works through the effects these images have on both a white and black audience. She says, 'when I was making this piece, I was thinking about the irony of these representations – as being not just a model for white people to think about black people but for black people to think about themselves.'

This piece shows the importance of representation, of seeing real black people and not just stereotypes in pop culture and public space.

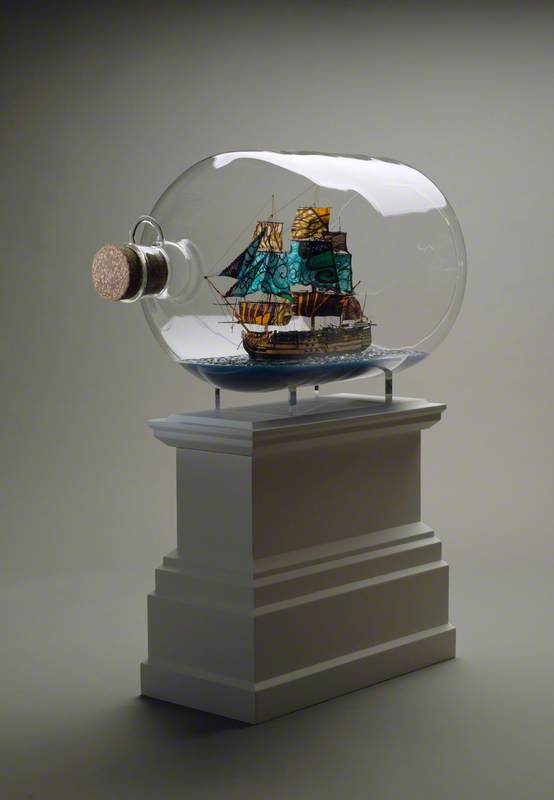

Yinka Shonibare (b.1962)

Yinka Shonibare is well known for his use of vibrant Ankara fabric, mining its complex multi-national history. Although it is often associated with the African continent, this fabric was originally inspired by Indonesian design and mass-produced in the Netherlands, hence it also being known as Dutch wax fabric. The Dutch colonial powers then sold it to colonies in West Africa, explaining its perceived Africanness. Shonibare sources his fabric from London, completing its global journey.

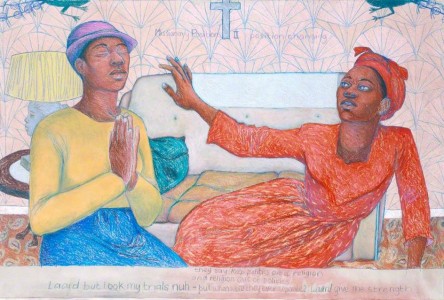

Shonibare dresses the two figures in The Crowning in luxurious eighteenth-century costumes (a regular motif of his) made of Ankara fabric to explore not only race and globalisation but also class. Class differences are brought into the present by the inclusion of the Chanel logo in the fabric print.

The artwork is a pastiche of the French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard's The Progress of Love: The Lover Crowned (now in the Frick Collection), a typically Rococo painting defined by its opulence and romanticism. While Fragonard's work portrays the luxurious lives of European aristocracy, Shonibare draws attention to the less considered lives of people of a lower social class or different race whose labours contributed to the wealth of these elites.

Fred Wilson (b.1954)

Fred Wilson's 2009 series Flag takes the flags of African and African diaspora nations and removes their colour, stripping them to black and white. On display, these flags sit alongside plaques which describe what the original colours and symbols represent, which often link back to European colonial nations.

View this post on Instagram

Flags are used to represent a national identity. In the case of formerly colonised countries, these identities remain linked to the European powers who controlled them. Using black and white also refers to the racial divisions in the power structures of these countries, inequalities which are still present in many former colonies.

These are artworks which are catalysts for a revised exploration of history which incorporates the significance of black lives. They bring history into the present by boldly displaying how the legacies of the transatlantic slave trade, empire and colonisation are felt today. As the media buzz around Black Lives Matter fades, these artists and many others will continue to produce powerful and thought-provoking work in order to build a more equal world.

Chloe Austin, curator, art historian and art writer

Further reading

Louisa Buck, Hew Locke talks monarchy and model boats, The Art Newspaper, 11th March 2019

Sonia Boyce, From Tarzan to Rambo..., 1987, Tate

Donald Locke, Trophies of Empire, 1972–1974, Tate

Donald Rodney, Land of Milk and Honey II, Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery