On a spring day, one year into the COVID-19 pandemic, Karla Black took a train from Glasgow, where she lives, to Edinburgh. The Turner Prize-nominated artist was headed for the Fruitmarket, one of Scotland's foremost contemporary art galleries, which was in the final stages of a two-year, £4.3m redevelopment and expansion into an adjacent warehouse. The gallery's opening exhibition was going to be a major retrospective spanning 20 years of the artist's career and covering – sometimes literally, it would turn out – the entire building.

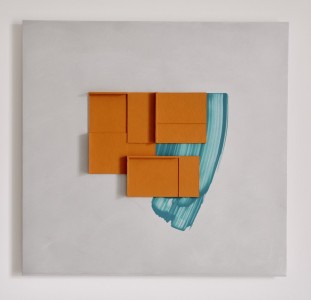

Punctuation is pretty popular: nobody wants to admit to much

(detail), 2008/2021, plaster powder, powder paint & thread by Karla Black (b.1972)

But Black still hadn't been inside the new space – a vast, double-height former fruit and vegetable warehouse that for years had been a nightclub – that she had been invited to fill with new work. She tends to make her monumental hanging, leaning, rising or spreading sculptures in situ, beginning by messing around with her materials in a kind of pre-language, childlike state of play. But, like most people, she had been stuck at home during lockdown. She was waiting until she was vaccinated. Life had been crumpled, to use a Karla Black kind of word. Now, it was opening up. On the train, she felt as though she was extending herself into space. It brought tears to her eyes.

'I was tied in a knot during lockdown,' Black tells me two months later, a week before the Fruitmarket reopening. 'I felt paralysed. I just couldn't do anything. I did some stuff out of necessity, like ripping up printer paper and soaking it in watercolour inks. But there was no real joy or freedom in it, just like there wasn't any in life. I have to feel some sort of freedom in myself to be able to do this.'

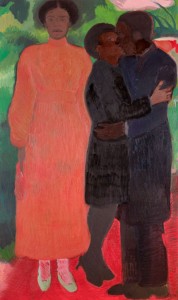

Waiver For Shade

(detail), 2021, thread, gold and copper leaf, Vaseline, earth, cosmetics & body moisturisers by Karla Black (b.1972)

Emerging out of this stasis, Black has made some extraordinary and moving work. She returned to the dark, dimly lit industrial warehouse, all exposed timber, steel and brick, a few days after that first visit and made Waiver For Shade. A floor sculpture out of earth scattered here in soft-edged squares, there in a mound. Copper threads hang from the high ceiling, glimmering in the slatted light. There are Vaseline smudges. Clumps of body butter. Crumpled gold leaf – a material that has begun to obsess Black in recent years 'because it's so elusive, easy to ruin, and somehow never as nice as it should be' – shines softly in the dark light like ore in a mine.

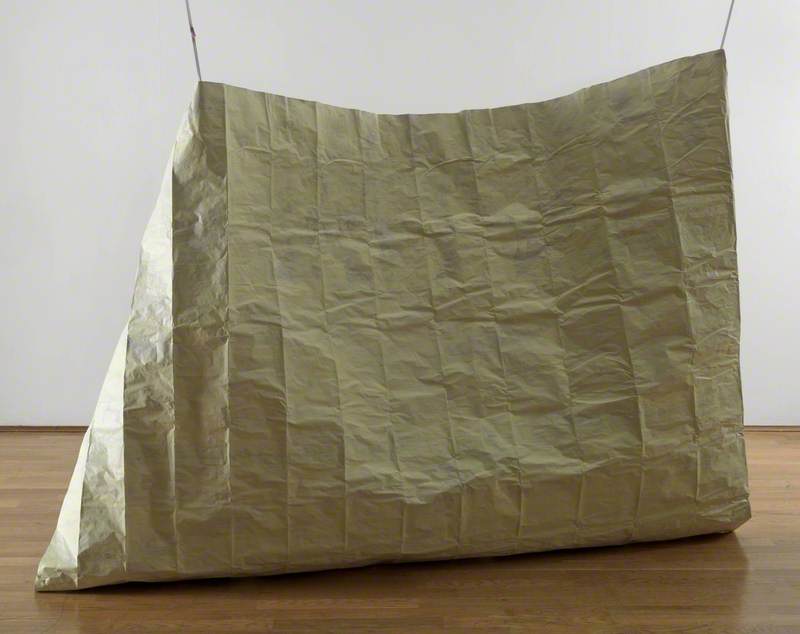

Punctuation is pretty popular: nobody wants to admit to much

(detail), 2008/2021, plaster powder, powder paint & thread by Karla Black (b.1972)

Back in the original gallery, as well as a room filled with retrospective and reimagined work, is a new floor sculpture covering the entirety of the upper gallery with pale pink plaster powder, powder paint, and almost camouflaged lines of thread. It's an exquisitely beautiful and confrontational work throwing its soft light up the walls of the white cube. It invites the viewer to stand on its threshold and control the impulse to throw herself into a fragile confection that, no matter how easily disturbed, is taking up all the space it can.

'I guess what I'm trying to do is ram this raw, creative moment into the institution and into the market,' Black says with a smile. Not that she wants to ascribe meaning to her work. 'I honestly can't even understand what the word "meaning" means,' she says. 'I can't talk about it with words, because language is even more of a construct than my sculptures, which exist in material reality. Whatever meaning my work has, it holds it within it. It doesn't point outside of itself.'

Installation view, Palazzo Pisani, Venice

2011, by Karla Black (b.1972)

I first interviewed Black a decade ago, as she was preparing to represent Scotland at the Venice Biennale in a show that was also curated by the Fruitmarket. Much has changed in those ten years. For a start, Black and her partner, the artist Tony Swain, now have a six-year-old daughter. She always accompanies her to shows and sometimes contributes to the work, whether by making a handprint with Vaseline on a window or throwing some Body Shop body butter at the ceiling.

Black is now fully established as one of Britain's major artists. Still, she comes across as she did then: warm, uncompromising, cerebral and obsessive. Her artistic preoccupations, like her signature materials, haven't fundamentally changed. 'I sort of feel like it's all the same,' she says. 'And it always will be because it's an unsolvable set of problems. They're not like problems in life, which you might want to eventually solve. It's just about being in amongst it.'

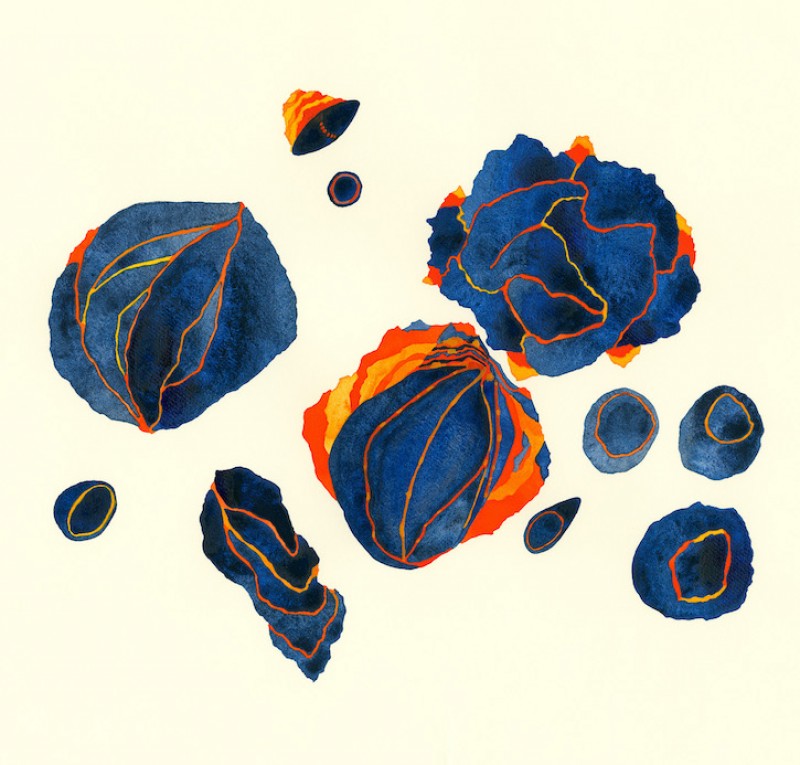

At Fault

(detail), 2011, mixed media by Karla Black (b.1972)

The problems, as she refers to them, often stem from her use of materials, traditional and otherwise. These include plaster powder, polythene dust sheets – which she might shake in a bin bag with chalk dust and then hang to create her ethereal, almost-not-there forms – sugar paper, cellophane, thread, Vaseline – which she mixes with paint so it never dries – nail varnish, make-up, body creams, and medicines for minor ailments. Another sculpture in the Fruitmarket retrospective was made by drizzling Gaviscon on the ground. It ate into the floorboards, like some self-made linocut.

Often, the materials Black uses incorporate her ongoing fascination with potentiality, rawness, life. 'It's like when I first started to use gold leaf,' she says, 'I think I wanted to make a frame. But then I sort of broke it and set it free.' At the same time, despite being drawn to substances that fade, crumple, break apart easily and elude permanence, she wants her work to last. Basically, a lot of what she wants is impossible.

Installation view of 'Karla Black, sculptures (2001–2021), details for a retrospective'

mixed media by Karla Black (b.1972)

'It's all about compromise,' she says. 'I want the forms to remain permanent but I also want this rawness and life in the material. I want the conditions of the studio but I want them in the institution, which is ridiculous.' Does it frustrate her that she wants what she can't have? 'Only in the way it has always frustrated me,' she says. 'I can't see another way. It's the limits of the physical world, you know, gravity, that frustrate me.'

Installation view of 'Karla Black, sculptures (2001–2021), details for a retrospective'

mixed media by Karla Black (b.1972)

Black grew up in a working-class community in Balloch, at the southern end of Loch Lomond. Her father was a mechanical engineer who fixed machines in a whisky factory and worked for Westclox in nearby Dumbarton, 'making tiny wee tools for fixing watches'. At home he was always painting a wall or knocking it down. Her mother worked in a bank and as a youth worker, and in her own youth had been a talented Highland and ballet dancer.

Both the performative and manual aspects of Black's artistic process derive from her parents. 'When I bend down, do stuff on the floor, paint a wall – it's the same body, the same hands, the same gestures, as my dad. I paint a wall how he paints a wall.' Has becoming a parent, watching her daughter interact with the world, influenced her work? 'I guess it just confirmed a lot for me,' she says. 'Even when I didn't have a child, I hadn't forgotten what it was to be one and do those things. That never went away for me. Isn't that what artists are?'

Looking Glass number 16

2021, mirror & glass paint by Karla Black (b.1972)

She left school at 16, and for a few years worked in a bank and as a journalist. 'I didn't go to art school until I was 23,' she says, 'but before that, I knew something was up. I knew I had to do something but I didn't know what. I guess I always scrabbled about in the dirt, or on the ground.' Eventually, after her brother bought her a bag of clay and a book about Rodin, she found her own way, and applied to study sculpture at The Glasgow School of Art.

These days, she prefers to think of her art in terms of its consequences. 'What it should make happen,' as she puts it. So what does she want it to do? 'It's about what we can do. How we can live. The space we can take up.' Yet the question of purpose has simultaneously never really troubled her. 'I've always been pretty sure about what it's for,' she says with a shrug. So, what is it for? 'It's not for anything,' she laughs. 'It's just human behaviour.' All she wants and has ever wanted is 'to make work that sort of hovers colour and material in front of your eyes'.

Looking Glass number 16

(detail), 2021, mirror & glass paint by Karla Black (b.1972)

When I interviewed Black in 2011, she told me she was obsessed with the bubbles left in the sink after washing up. She wanted to recreate them, make them last forever. I tell her that in the intervening ten years I have seldom done the washing up without thinking about this, and she laughs. 'I'm still obsessed by that,' she says. 'Also, the marks on taps and shower screens made by soap. Rain marks on a window. One of the things I want to do is mix watercolour inks with bubbles, and try and get marks on a piece of paper.' She sighs. 'You can't really get it though. Whenever I see these things I always think "if only I could do that".'

Karla Black on her earlier works:

'There are two forms – one that sits on the floor, one that stands. I remember making the pink and yellow chalked sugar paper, stretching polythene over it, and being really happy with what I achieved with the one on the floor. It's about trying to make good enough forms to present the material detail plopped on it.'

'Vanity Matters is very painterly. My work skirts close up against other mediums. It gets close to painting, installation, land art, but it's always a sculpture. Vanity Matters is very, very nearly a painting.'

'Don't Adapt, Detach was from one of my first really big shows in a really big space in Zurich. It was the first thing you saw when you walked through the door. I painted dots on cellophane, then sprayed it with athlete's foot powder. The surface and layers are really important. I didn't know if it was going to be a hanging work. It ended up a scrunched-up form on the floor, just peeking out when you went in the door.'

Chitra Ramaswamy, journalist and author

'Karla Black: sculptures (2001–2021), details for a retrospective' at Fruitmarket, Edinburgh, runs until 24th October 2021

This content was supported by Creative Scotland and the Scottish Contemporary Art Network