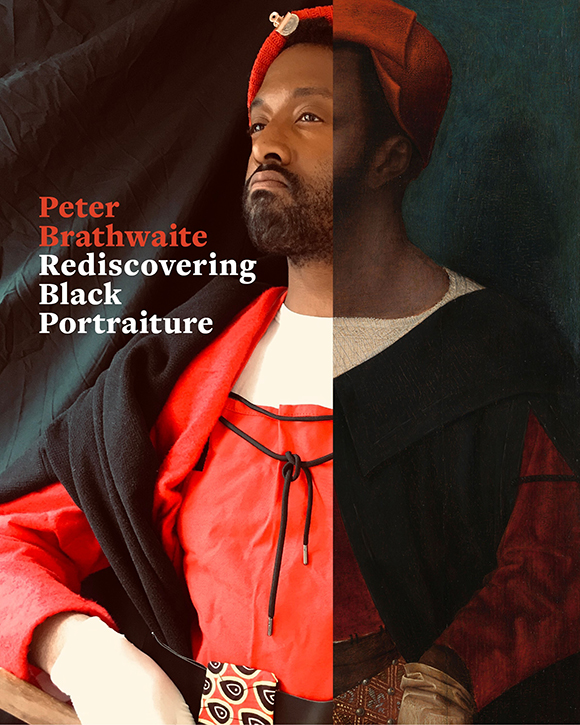

Since early 2020, opera singer and broadcaster Peter Brathwaite has researched and reimagined more than 100 artworks featuring Black sitters. Initially in response to the Getty Museum Challenge – which prompted people to restage famous paintings using household items – over 50 of Brathwaite's inventive interpretations are presented in Rediscovering Black Portraiture (Getty Publications), alongside personal reflection and contributions from experts in visual culture.

An extraordinary journey through representations of Black subjects in Western art, from medieval Europe through the present day, Rediscovering Black Portraiture offers a nuanced look at the complexities and challenges of building identity within the African diaspora and how such forces have informed Black portraits over time.

The African King Caspar

1654 or 1659, oil on canvas by Hendrick Heerschop (1620/1621–c.1672)

'The African King Caspar' by Hendrick Heerschop

re-creation by Peter Brathwaite (with photographic partner Sam Baldock)

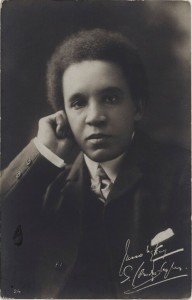

As a Black British opera singer, I am used to being a rare breed. Moreover, I am accustomed to having quizzical glances cast in my direction, as if I am something of a novelty or a curious anomaly. A large part of my musical career to date has been based on balancing and reconciling the tricky dichotomy of otherness in relation to myself and the canon of Western classical music that I love and love to perform. And given that they are so few and far between, representations of people who look like me in the classical canon have always been of interest. As a student of opera, I clung to the album covers of the African American soprano Leontyne Price and a black-and-white postcard portrait of the Black British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor.

When I encountered the Getty Museum Challenge during the coronavirus pandemic in 2020, my feed was awash with people who had taken up the challenge, re-creating their favourite artworks using everyday items found at home. The submissions exposed the depressing truth that most of the so-called great artworks we choose to platform and celebrate do not tell the stories of people of colour – the global majority. I decided to revisit a search term I'd been compelled to explore at the very start of my opera career: 'Black portraiture'.

Follower of Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646–1723): Portrait of a gentleman in livery and wearing an enslaved collar. Reworked with Santa suit, bin, bbq and buckpot from mum. Rediscovering #blackportraiture through #gettymuseumchallenge. #gettychallenge pic.twitter.com/wWT2srSiFy

— Peter Brathwaite (@PeterBrathwaite) June 10, 2020

By re-creating as many Black figures as possible, using the stuff in my house and the camera of my iPhone 7, I would commit to rescuing their voices from oblivion – and in doing so, challenge how art history has been told. Many of the Black sitters I have embodied in my re-creations are muted or marginalised. Some of them are completely anonymous, depicted by white artists solely to reinforce racist ideals. Stepping into the shoes of these long-muted Black figures has made space for me to chip away at and crack this Eurocentric edifice. I have adopted and adapted these works of art in the hope that by making these depictions completely my own, the lives of the individuals I portray might be unshackled, reimagined, and, most importantly, seen.

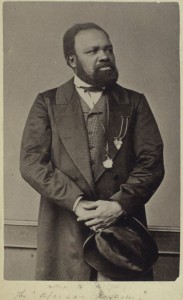

Ira Aldridge as Othello, the Moor of Venice by James Northcote

'Ira Aldridge as Othello, the Moor of Venice' by James Northcote

re-creation by Peter Brathwaite (with photographic partner Sam Baldock)

Born in New York City, Aldridge was one of the greatest Shakespearean actors of his age – but he was Black. Unable to work in the United States, he travelled to England in the 1820s and became the first Black actor to play the role of Othello in Britain. London was, at the time, England's cradle of proslavery lobbying, while Manchester opposed slavery. Perhaps in honour of this stance, the Royal Manchester Institution commissioned the Northcote portrait shortly after Aldridge's acclaimed performances at the city's Theatre Royal.

Aldridge's intelligent professional choices and acting talent gave him a platform to challenge his audiences' expectations. He was both a brilliant performer and an effective activist, and I feel proud, as a Manchester native, to know that this portrait was commissioned in my hometown.

The Paston Treasure by Dutch School

The Paston Treasure

(formerly titled 'The Yarmouth Collection') c.1665

Dutch School

'The Paston Treasure' by Dutch School

re-creation by Peter Brathwaite (with photographic partner Sam Baldock)

This painting, which is thought to have been commissioned by Sir William Paston, depicts just a fraction of the treasures scooped up during the Paston family's extensive travels, including tropical fruit, exotic animals, priceless curiosities, and a Black man exquisitely clad in velvet and silk. His flesh tones are finely rendered, but is he even really there? His presence is all that visually links this display of wealth to the brutal conditions of chattel slavery. His depiction, to me, represents a process of being dehumanised twice over – first as a piece of property, and then again because this scene is so far removed from his actual reality.

My re-creation asks what it means to take up space as a Black man. It was reworked with Afro hair products, Côte d'Ivoire prints, Granny's patchwork quilt, Jessye Norman and Leontyne Price records, and luggage from my family's arrival in the UK.

The Sybil Agrippina by Jan van den Hoecke

The Sibyl Agrippina

c.1630, oil on canvas attributed to Jan van den Hoecke (1611–1651)

'The Sibyl Agrippina' attributed to Jan van den Hoecke

re-creation by Peter Brathwaite (with photographic partner Sam Baldock)

The Sibyls were oracles, or priestesses, in ancient Greece. This depiction of a Black woman as the 'Egyptian' Sibyl follows a tradition in Western art but also speaks to the increased availability of Black models in the Netherlands as a result of the growing trade in enslaved Africans. The figure's whip and crown of thorns allude to the suffering of Christ at the Crucifixion. The inscription on the banner reads Siccabitur ut folium ('He will shrivel like a leaf'). It is likely that this representation would have been understood, in its time, against the backdrop of debates surrounding the Christianisation of enslaved communities.

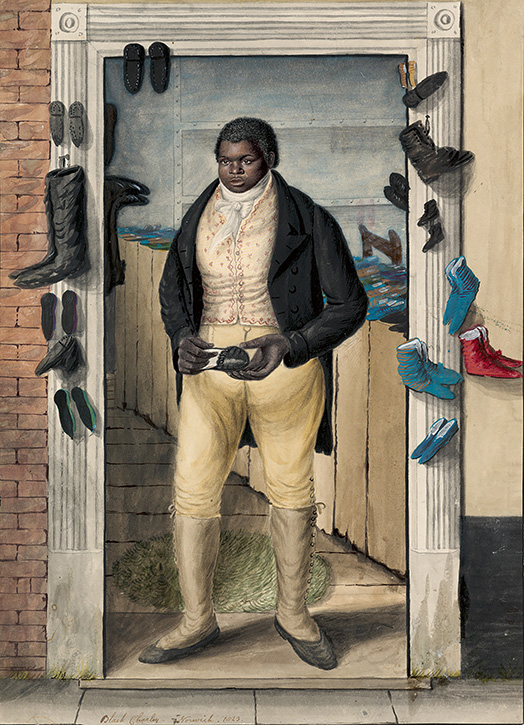

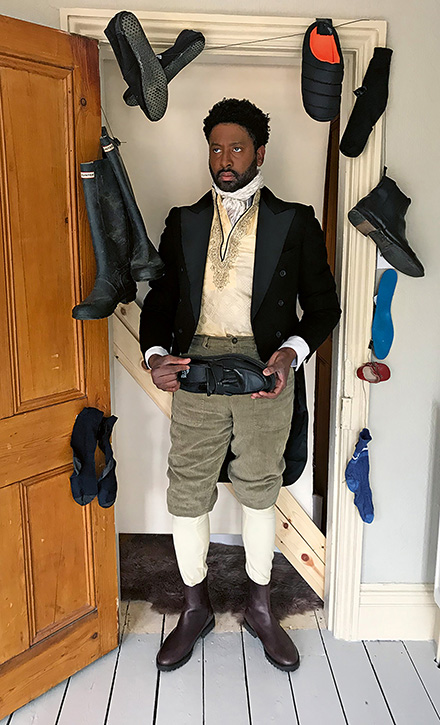

"Cotton, Norwich" by John Dempsey

"Cotton", Norwich

c.1823, watercolour by John Dempsey (1802/1803–1877), in 'A Folio of British Street Portraits', 1824–1844

'"Cotton", Norwich' by John Dempsey

re-creation by Peter Brathwaite (with photographic partner Sam Baldock)

The original artwork comes from Dempsey's extensive folio of the British working class. Reworked with an array of footwear that includes my red baby shoe, the portrait is thought to depict Charles Willis Yearly, who sold second-hand shoes in Norwich. Neither servant nor enslaved, Charley effectively punctures the myth of Georgian England's homogeneity.

Captured in the doorway of his shop, Charley wears an embroidered waistcoat, a double-breasted coat, and a starched cravat tied with a flourish that lends an air of superiority. Breeches were somewhat old-fashioned by the 1820s, which suggests that either Dempsey painted Charley at an earlier date or, like the shoes hanging from the door frame, his outfit was second-hand. I wonder whether Charley's disproportionately large hands might be Dempsey's not-so-subtle way of illustrating that Charley not only sold shoes but perhaps also made and mended them.

Study of the Model Joseph by Théodore Géricault

Study of the Model Joseph

c.1818–1819, oil on canvas by Théodore Géricault (1791–1824)

'Study of the Model Joseph' by Théodore Géricault

re-creation by Peter Brathwaite (with photographic partner Sam Baldock)

Joseph's full name was not recorded, but nineteenth-century accounts indicate that he was born in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) around 1793. As a young man, he emigrated to France and worked as an acrobat in Paris, where he caught the attention of Géricault. Joseph was a principal model in Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa, a colossal painting that depicts a shipwreck off the coast of northwest Africa. By the 1830s, Joseph had been recruited to model at Paris's prestigious École des Beaux-Arts.

Géricault's study is one of the most developed renderings of Black flesh tones and Afro hair that I have encountered. His attention to the balance of warm and cool tones in Joseph's skin makes this portrait luminous, inviting us into the world of an actual, distinct person.

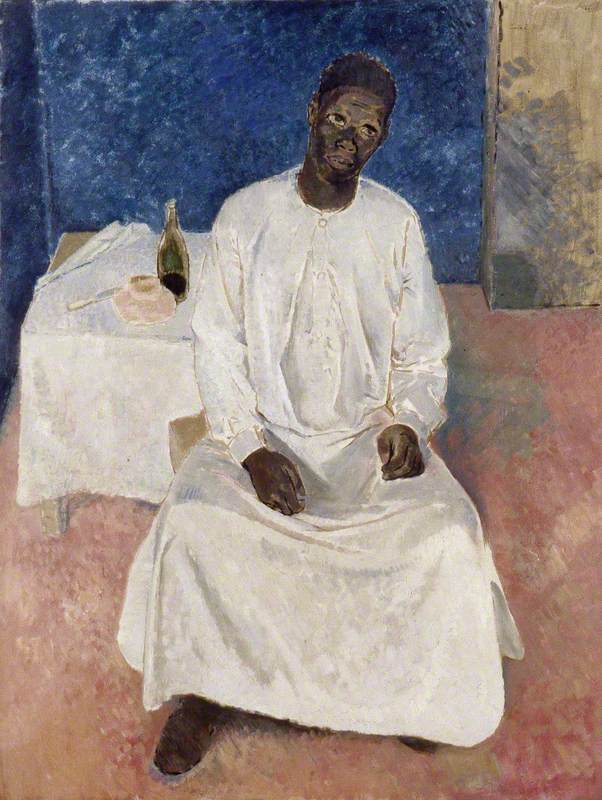

Aïcha by Félix Vallotton

Aïcha

1922, oil on canvas by Félix Vallotton (1865–1925)

'Aïcha' by Félix Vallotton

re-creation by Peter Brathwaite (with photographic partner Sam Baldock)

Aïcha Goblet, the 'Venus of Montparnasse', was born around 1898 in Hazebrouck, France. The daughter of a juggler from Martinique, she performed in the circus as a child and set her sights on Paris at age 16. There she rose to prominence as an artist's model, posing for the likes of Man Ray and Amedeo Modigliani. As a music hall dancer and an actor, she never became as famous as Josephine Baker but was esteemed by audiences and critics alike.

In Vallotton's likeness, a pensive Goblet looks away from us, her signature head wrap shimmering in the dappled light. She is portrayed as an artist, not a racial type.

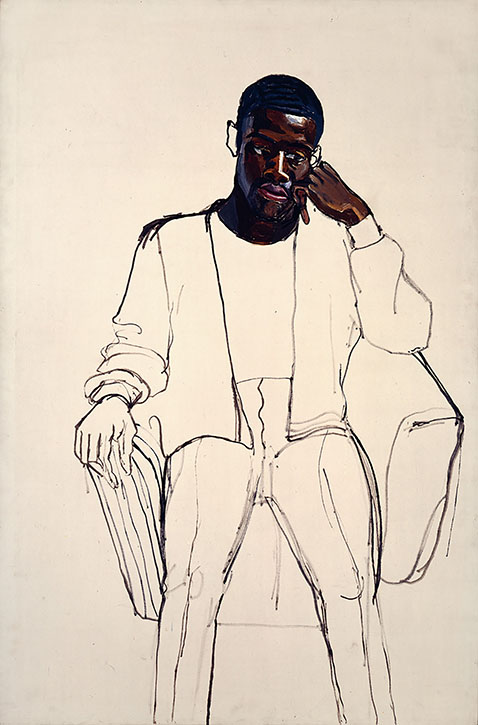

James Hunter (Black Draftee) by Alice Neel

James Hunter (Black Draftee)

1965, oil on canvas by Alice Neel (1900–1984)

'James Hunter (Black Draftee)' by Alice Neel

re-creation by Peter Brathwaite (with photographic partner Sam Baldock)

Neel's portraits document the diverse tapestry of people she encountered daily while living and working in New York City. This example is particularly striking for having been left deliberately unfinished. Nobody knows what happened to its subject, James Hunter, whom Neel met by chance soon after he was drafted for service in the Vietnam War. Due to leave within a week, Hunter never returned for a second sitting. The stark, sketchy outline of his absent body contrasts with his fully realised face and the hand on which it rests. Neel seems to embed all of the unfulfilled potential of this life into her canvas. His expression is haunting.

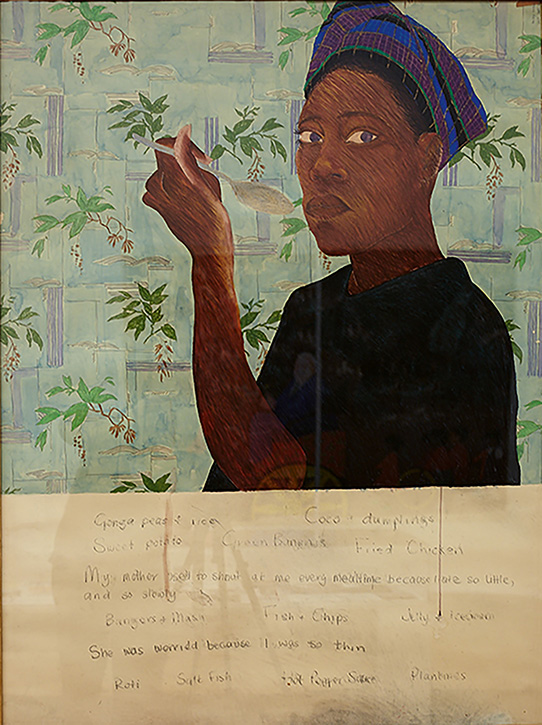

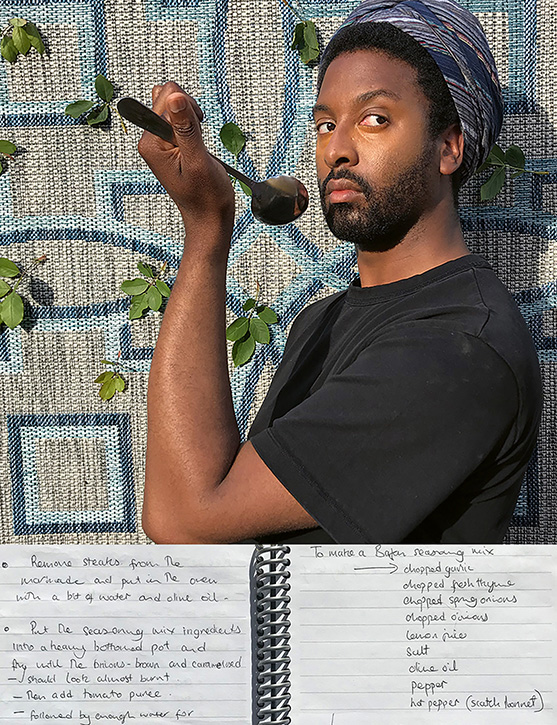

Rice n Peas by Sonia Boyce

Rice n Peas

1982, pastel, watercolor & pencil on paper by Sonia Boyce (b.1962)

'Rice n Peas' by Sonia Boyce

re-creation by Peter Brathwaite (with photographic partner Sam Baldock)

In the lower portion of this work, we read a scribbled recollection alongside a list of Afro-Caribbean and British foods, and above the faded scrawl is Boyce herself, positioned in front of what looks like floral-patterned wallpaper. Spoon clutched awkwardly in her raised hand, she looks out to us, lips closed, eyes wide, hair tied. The portrait is striking and complex. Boyce has re-created herself in a stylised way. But there is a defiance in her penetrating gaze, as if challenging the viewer. Boyce is dictating the terms of how we view her, how we judge her, how we know her.

In her image, I see all of the anonymous Black figures I have encountered in Western art on this journey of rediscovering Black portraiture – those who were previously silenced, unable to articulate themselves in the face of whiteness. Boyce reclaims the very space of the portrait, making it truly hers, ours, mine. My reworking is with a notebook containing my mother's Bajan recipes.

Peter Brathwaite, opera singer, photographer and broadcaster

Rediscovering Black Portraiture is available to purchase from the Art UK Shop

This excerpt is from the new publication Rediscovering Black Portraiture by Peter Brathwaite, with contributions by Cheryl Finley, Temi Odumosu, and Mark Sealy – an extract from the Prologue, as well as a sampling of the re-creations, by Peter Brathwaite © 2023 J. Paul Getty Trust. Used with permission