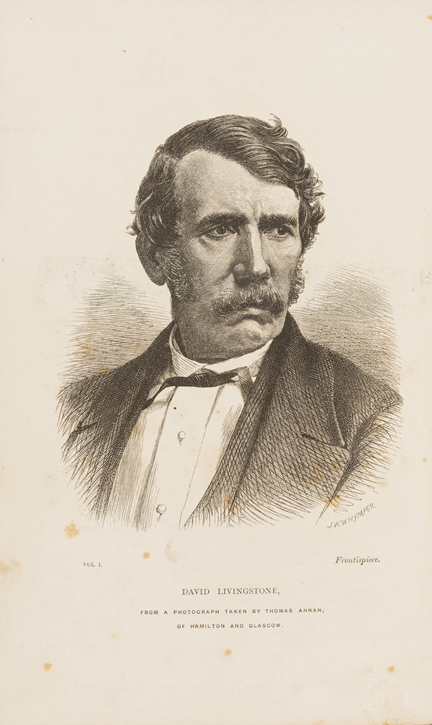

David Livingstone (1813–1873) was a Scottish physician and Christian missionary who spent almost 30 years travelling and working in Southern and Central Africa. A life-long abolitionist, Livingstone sought to transform Western perceptions of the continent.

Image credit: David Livingstone Trust

David Livingstone (1813–1873)

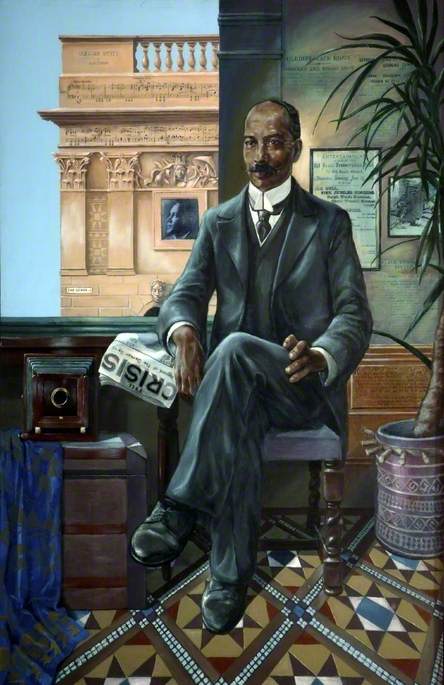

frontispiece of a first edition version of Livingstone’s last book, 'The Last Journals of David Livingstone: In Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death' by David Livingstone, James Chuma, Abdullah Susi and Horace Waller

The David Livingstone Birthplace Museum, located in Blantyre, South Lanarkshire, is unique in being the only Scottish independent museum dedicated to preserving the legacy of Livingstone. The Museum, which reopened in July 2021 following a large redevelopment project, highlights the previously untold stories of those who were crucial to Livingstone's expeditions, whilst presenting his story within the important context of European colonisation. As explained on its website, the Museum is committed to: 're-examining his work within the complex and painful realities of slavery, colonialism and nineteenth-century European attitudes towards African people and community groups.'

The Museum is in a unique position: they aim to challenge unconscious bias and privilege whilst committing to telling untold and sometimes contested portrayals of Black history.

Image credit: Walnut Wasp / David Livingstone Trust

David Livingstone Birthplace Museum

In adding a selection of objects from the David Livingstone Birthplace collection to Art UK, we are expanding the notion of an 'artwork' beyond the Westernised perspective to include objects that are considered a form of art by those who made, used and appreciate them.

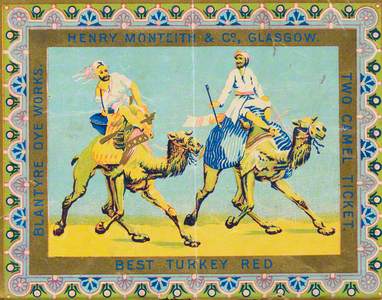

Auld Lang Syne Handkerchief

Auld Lang Syne Handkerchief c.1850

unknown artist

Following his birth in the mill workers' accommodation, Shuttle Row (where the Museum is located), David Livingstone began working in the cotton mill aged 10. He began work as a piecer, crawling under the cotton spinning jenny machines to piece together the broken cotton threads, a notoriously dangerous position. He was later promoted to a spinner in the mill when he reached the age of 19.

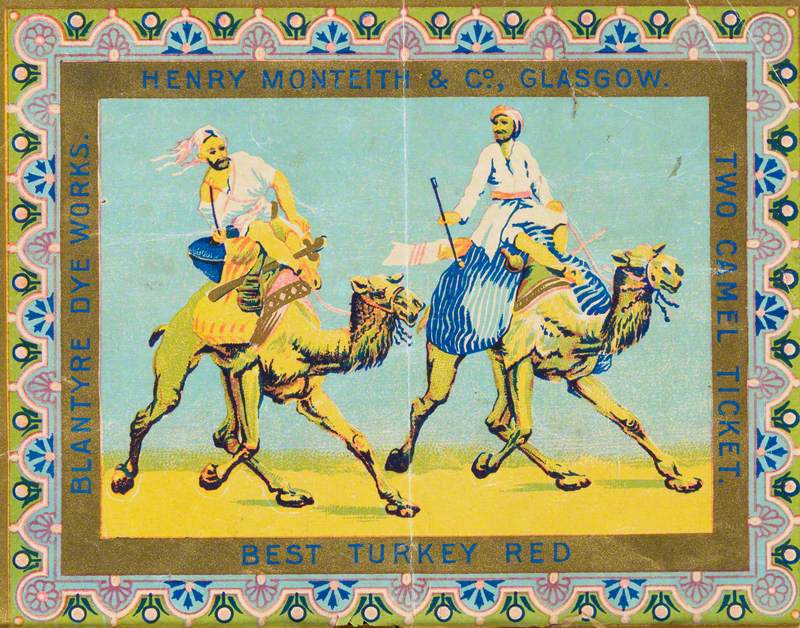

This handkerchief was made at the Blantyre cotton works c.1850 and prominently displays the title of popular Robert Burns's song Auld Lang Syne. The striking red colour comes from the Turkey Red dye, a dye that was made using Rubia plant extracts to achieve bright and vibrant pigmentation. The cotton works was one of the first mills in Scotland to produce this dye and, at peak production, it is estimated that around 200 handkerchiefs were being produced every 10 minutes. Both the industrial revolution and the colonies in America paved the success of the Blantyre Cotton Works, with the exploitation of enslaved people having a direct impact on the accomplishments of the mill.

Beaded Gourd

During Livingstone's travels across Africa, he collected a variety of objects. The Museum is committed to conducting thorough provenance research into all the items in the collection (see the museum's statement below).

This highly decorative storage container was made from a dried calabash gourd, with a stopper and leather handle added for practicality. The coloured beadwork is both striking and intricate, however, this beaded gourd is not merely decorative. Gourds such as this one were most likely used to store and carry liquids, such as water, milk or beer.

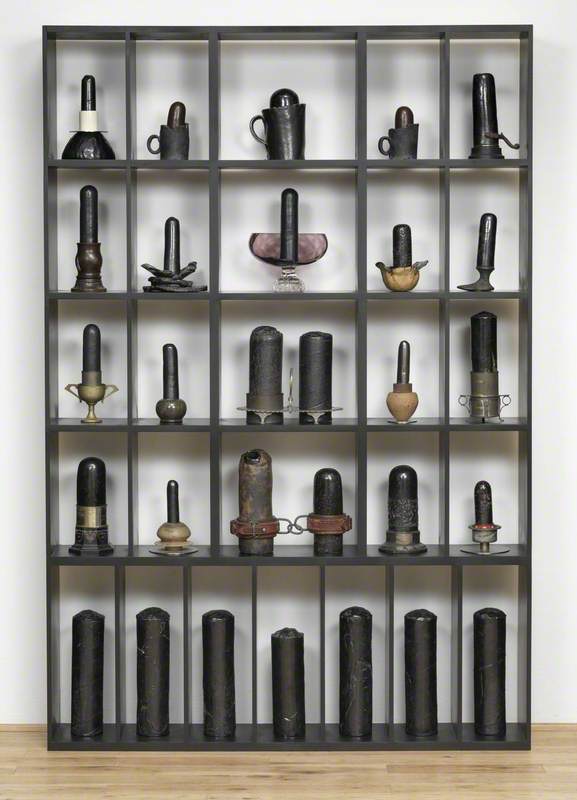

Ancestor Twin Votives

Diviners, sometimes referred to as traditional healers, would have carried small wooden carvings such as these within their medicine kits, indicating that they held a strong significance in relation to health and well-being. Whilst the specific use of the examples held in the Museum's collection is currently unknown, carved figures with bent knees are thought to be symbolic of living beings amongst the Kongo people of Central Africa.

Comb

This intricately carved wooden comb was gifted to Livingstone by the wife of an African chief. Unfortunately, but perhaps unsurprisingly, the name of the woman it once belonged to was not recorded. Research does, however, suggest that this woman formed part of a community that was local to the Zambezi River in Eastern Africa.

The Pilkington Jackson Tableaux and Tales from the Tableaux

Image credit: David Livingstone Trust

The Pilkington Jackson Tableaux

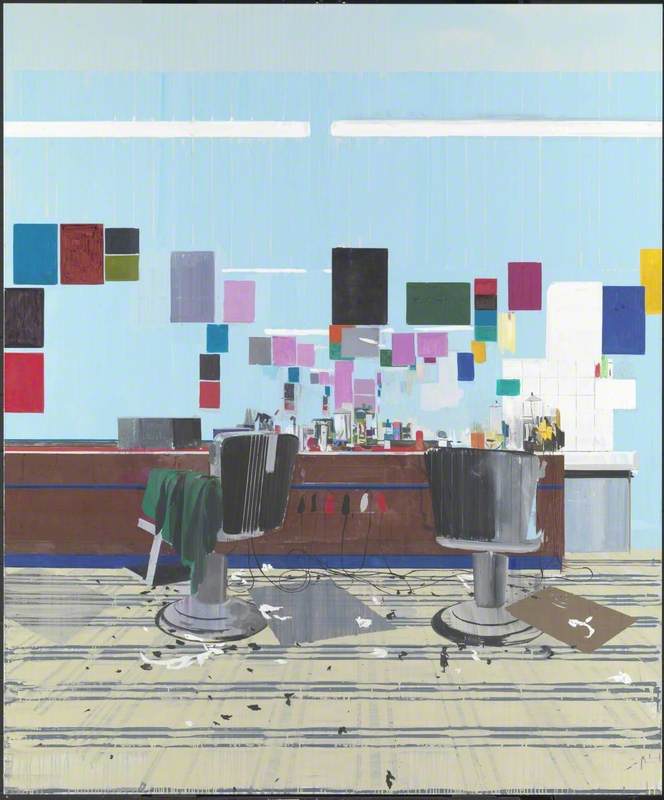

Visitors to the Museum can wander through the newly restored Pilkington Jackson Tableaux, a series of eight sculptures created in the 1920s by Charles d'Orville Pilkington Jackson. The sculptures act as a timeline, depicting Livingstone in various heroic scenes throughout his travels.

Image credit: David Livingstone Trust

The Pilkington Jackson Tableaux

However, upon entering the Legacy Room, the final room of the museum, visitors are greeted by Tales from the Tableaux, an audio-visual animation that brings the Tableaux to life. The animation, scripted by author Petina Gappah, highlights the hidden histories of the Southern and Central African figures depicted within the sculptures. Motshipi, one of the wives of Chief Sechele I and Mjakazi, an enslaved woman, are just two of the figures brought to life in this animation which seeks to bring to the fore the histories of those Livingstone encountered.

Tales from the Tableaux is accompanied by a series of talking head interviews, filmed in collaboration with the Scotland Malawi Partnership. This video series discusses the impact that Livingstone had and continues to have on individuals, communities, and countries. Some of these impacts are positive, highlighting how Livingstone inspired others to be vocal in their activism, or to incorporate God and science into their lives. Crucially, these interviews also discuss the negative implications of Livingstone's work in Africa and how, despite being an abolitionist, his missionary work and travels should not always be perceived in a positive light.

The David Livingstone Birthplace Museum seeks to re-examine the way Livingstone is depicted in history, recontextualising his story to include the vital narratives of those he encountered throughout his lifetime. The Museum was runner-up in the recent Museums + Heritage Permanent Exhibition of the Year award in 2022.

Aimee Murphy, Art UK's Collections Engagement Officer for Scotland

Read the David Livingstone Birthplace Museum's statement below:

How was the collection acquired?

We hold approximately 6,000 objects in our collection, each one cared for in accordance with best practice museum standards. We hold many objects relating to David Livingstone, Blantyre and the Blantyre Cotton Works, plus items of African origin.

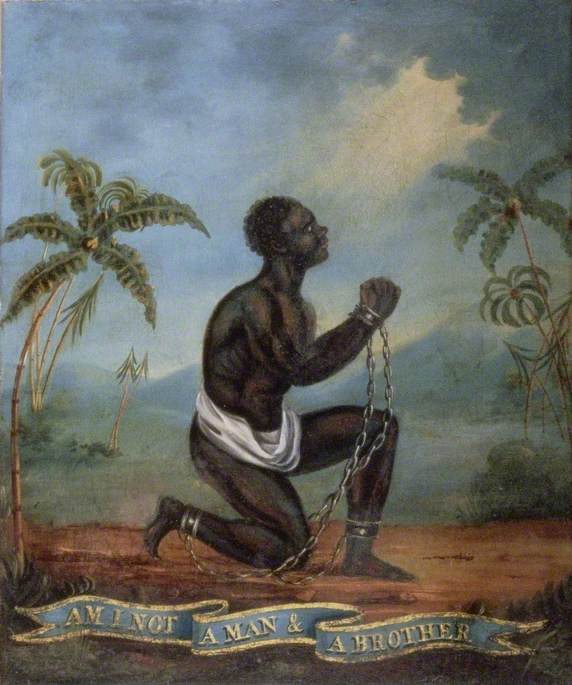

Through our historically significant collection, we can tell the story of Livingstone and learn the history that Scotland shares with the many Central and Southern African countries that Livingstone lived and worked in. We also hold objects that testify to the history and brutality of the East African Slave Trade and show the social and political impacts of nineteenth-century missionary work, imperialism and colonialism.

Historic issues with the Museum's documentation mean that we do not know the source of many objects in our collection. We do know that many objects were donated following an open call for objects when the museum was founded in 1929. Many objects were donated by Livingstone's descendants, organisations Livingstone was affiliated with, as well as the local Blantyre community. A large part of our collection was also donated by people with no direct link to Livingstone, but who lived and worked in various African countries.

It is likely that many objects of African origin in our collection were acquired by their original owners through trade networks, colonial offices, and missionary work. In many cases, the information about the communities who made and originally owned these objects has been lost.

Have you considered repatriating any of the Museum's objects?

Yes. We have started the process of carrying out systematic research on the objects that we hold in our collection by using the documentation we do have, in addition to research into the communities who likely once made and used the objects.

We continue to improve and update our exhibition and museum interpretation as we learn more about our collection and engage with communities and international partners. This is an ongoing commitment, as outlined in our organisational values.