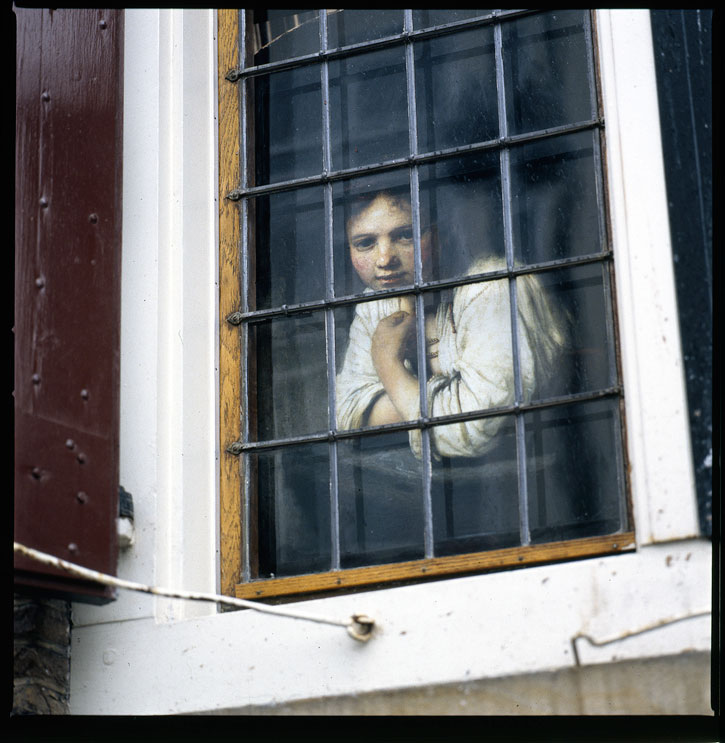

It would be easy for me, as an art gallery Director, to say that one of the world's greatest paintings is in the collection in my care. It comes with the territory of leadership to be a passionate advocate for the 'home team'. But the fact is that I took the job at Dulwich Picture Gallery because of a specific painting. A painting so haunting, so powerful, that I call it the 'Mona Lisa of London'.

'Girl at a Window' in situ at Dulwich Picture Gallery

1645, oil on canvas by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

In 1645, Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) was at the top of his game. He had purchased an expensive property on the Breestraat in central Amsterdam. He was receiving numerous commissions and was established as the most creatively exciting artist working in Amsterdam, particularly in the wake of his large-scale Night Watch (1642, Rijksmuseum).

The French writer Roger de Piles (1635–1709), who was fortunate enough to own Girl at a Window towards the end of the seventeenth century, recorded an anecdote that Rembrandt had displayed the painting at the window of his large house. Passers-by stopped in wonder that the servant girl had been standing still for so long.

Not only does this story reinforce the artist's reputation for capturing life with veracity sufficient to fool fellow humans into thinking that oil paint on canvas is flesh and blood, but it also gave the painting its title. For our girl is resting on a stone ledge, not necessarily a window. The notion of it having graced Rembrandt's window was enough to cement its popular name.

The power of Girl at a Window comes from the economy of detail. The background is a carefully rendered grey void. The paint application is thick where it needs to be – on the ruddy highlights of the girl's cheeks and the white of her blouse – but lightly applied in the background. She looms out of the darkness, stark and clearly outlined. Her unruly red hair curls around her face, slightly tamed by a velvet skullcap. The clothes are not her own: the shirt is too baggy; the cap too ornamental. The costume comes from Rembrandt's large and varied dressing up box, allowing the girl to enact an imagined role within the painting.

All of the above would be enough to constitute a very good painting. But there are three details in this picture which take it up a notch, to make this an exceptional painting:

Firstly – the arms.

Detail of 'Girl at a Window' showing the arms

1645, oil on canvas by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

Our girl bends her left arm up towards her neck. She seems to beckon us while simultaneously containing herself in the space. At first glance, we could describe the perfection of her skin, but closer looking reveals the all-too-human tan line of someone who spends much time outdoors and, best of all, red pockmarks to indicate mosquito, bed bug or flea bites.

Secondly – the gaze. Rembrandt gives us a masterclass in looking-while-not-looking. We think the girl catches our eye, but is she, in fact, looking through us? Caught in her own inner thoughts? Unaware of our presence? This leads us to consider to the ambiguity of her identity. She could be a servant pausing in her work, or a model or family member daydreaming while posing for the artist, or a young prostitute, weary of her trade.

Thirdly – one final touch of paint.

Detail of 'Girl at a Window' showing the nose

1645, oil on canvas by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

A tiny flash of white, potentially the very last mark in oil that Rembrandt made on this canvas, highlighting the tip of the girl's nose.

The dilemma of deciding when a work is 'finished' has plagued artists throughout history. For instance, Picasso famously thought that to finish a painting was to 'kill' it. Masaccio may well have lamented the buon fresco technique that limited the parameters of a day's work. Berthe Morisot was erroneously criticised for not being disciplined enough to 'complete' a picture (when, on the contrary, she was authoritative enough to declare when a work was ready).

A genuine fear in all creative output is the risk of taking something too far. With this one, final, assured spot of paint, Rembrandt animated his subject. Our girl, surely, is just about to snap out of her reverie and notice us, the viewer. But, for now, she is suspended on the brink of action. Flawed, captivating, real: Rembrandt at his best.

Jennifer Scott, Director of Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, and co-curator of the exhibition 'Rembrandt's Light' at Dulwich Picture Gallery from 4th October 2019 to 2nd February 2020